We present our experience on idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), before and after the introduction of a specific diagnosis and management protocol.

MethodA descriptive retrospective study was conducted on patients with IIH over a 25 year period (1990–2015), comparing the last 7 years (after introduction of the protocol) with the previous 18 years.

ResultsAmong the 18,865 patients evaluated, there were 54 cases of IIH (29 infants and 25 children). A comparison was made between the two time periods: 32 cases in 1990–2008—published in An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:400-6—, and 23 cases in 2008–2015. In post-protocol period, there were 13 patients aged between 3–10 months (62% males) with transient bulging fontanelle, and 10 aged between 2 and 14 years (50% males), with papilloedema. A total of 54% of infants had recently finished corticosteroid treatment for bronchitis. In the older children, there was one case associated with venous thrombosis caused by otomastoiditis, one case on corticosteroid treatment for angioma, and another case treated with growth hormone. Transfontanelle ultrasound was performed on all infants, and CT, MRI and angio-MRI was performed on every child. Lumbar puncture was performed on 2 infants in whom meningitis was suspected, and in all children. All patients progressed favourably, with treatment being started in 3 of them. One patient relapsed.

DiscussionCharacteristics and outcomes of patients overlap every year. IIH usually has a favourable outcome, although it may be longer in children than in infants. It can cause serious visual disturbances, so close ophthalmological control is necessary. The protocol is useful to ease diagnostic decisions, monitoring, and treatment.

Se presenta nuestra experiencia en hipertensión intracraneal idiopática (HII) preimplantación y postimplantación de un protocolo específico de actuación.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de los pacientes con diagnóstico de HII en 25años (1990-2015), comparando los últimos 7 años (tras implantar protocolo) con los 18 previos.

ResultadosDe 18.865 pacientes valorados en 25 años, hay 54 casos de HII (29 lactantes y 25 niños mayores). Se comparan ambos periodos: 32 casos de 1990-2008 —publicados en An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:400-6— y 23 de 2008-2015. En el periodo posprotocolo, hubo 13 pacientes entre 3 y 10meses (62% varones) con abombamiento transitorio de fontanela y 10 entre 2 y 14 años (50% varones) con papiledema. El 54% de los lactantes habían finalizado recientemente tratamiento corticoideo por bronquitis. En los mayores, un caso asoció trombosis de senos venosos por otomastoiditis, otro tratamiento corticoideo por angioma y otro tratamiento con hormona de crecimiento. Se hizo ecografía transfontanelar a todos los lactantes; TAC, RM y angioRM a todos los mayores, y punción lumbar a 2lactantes (por sospecha de meningitis) y a todos los mayores. Todos los pacientes evolucionaron favorablemente; solo en 3 se instauró tratamiento. Una paciente recidivó.

DiscusiónLas características y la evolución de los pacientes son superponibles en todos los años. La HII suele tener un curso favorable, aunque puede tardar en resolverse en niños mayores y presentar graves repercusiones visuales, por lo que precisa estrecho control oftalmológico. Destacamos la utilidad del protocolo para facilitar la toma de decisiones diagnósticas, de seguimiento y tratamiento.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a disease defined by clinical criteria that include signs and symptoms caused by raised intracranial pressure (headache, papilloedema and visual impairment) in the absence of abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition, and ruling out of other possible causes of intracranial hypertension (space-occupying lesions, head trauma, encephalitis and meningitis) by neuroimaging or other diagnostic methods. Thus, it is a clinical and differential diagnosis.

Other terms are used to refer to this disease, such as benign intracranial hypertension; however, this term is somewhat controversial because IIH can cause significant ophthalmologic complications and even blindness. It was classically known as “pseudotumour cerebri,” a term that some authors like Wall would rather avoid,1 while others like Friedman2 continue to use because in their view it comprehends “true” IIH (of an unknown cause) as well as intracranial hypertension secondary to any of various diseases or drugs.

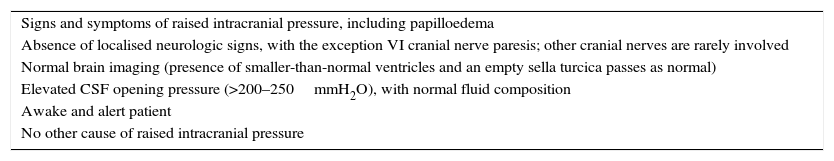

The diagnosis is fundamentally clinical and based on the modified Dandy–Smith criteria3 (Table 1). Measuring the CSF opening pressure, which is done with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, is not easy, especially in children. There are descriptions of variations of 24–47cmH2O under circumstances such as crying or performance of the Valsalva manoeuvre.4 Furthermore, there is no consensus on normal pressure values in infants,5 and there have also been cases of children with IIH that presented with normal intracranial pressures.6,7 Sedation may be necessary to do the measurement. Pressure thresholds higher than those classically used in adults have been proposed for children aged less than 8 years. Thus, the cut-off points that are commonly used are the following8:

- •

Children aged less than 8 years: a CSF pressure of more than 280mmH2O should be interpreted based on the associated signs and symptoms.

- •

Children aged more than 8 years: a CSF pressure of 200mmH2O is considered the upper bound of normal; pressures between 200 and 250mmH2O should be interpreted based on the associated signs and symptoms, and pressures of more than 250mmH2O as elevated.

Modified Dandy–Smith criteria.

| Signs and symptoms of raised intracranial pressure, including papilloedema |

| Absence of localised neurologic signs, with the exception VI cranial nerve paresis; other cranial nerves are rarely involved |

| Normal brain imaging (presence of smaller-than-normal ventricles and an empty sella turcica passes as normal) |

| Elevated CSF opening pressure (>200–250mmH2O), with normal fluid composition |

| Awake and alert patient |

| No other cause of raised intracranial pressure |

In clinical practice, there are cases of transient intracranial hypertension in patients with normal imaging findings, which can be identified by the presence of a bulging fontanelle that resolves spontaneously in a few days in infants, and of papilloedema in older children.

In this study, we analyse our experience with patients with IIH over 25 years, comparing the data for the periods before and after the introduction of a specific protocol for its management.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a retrospective descriptive study of patients with an IIH diagnosis assessed in our paediatric neurology unit in the 25 years it has been operating (1990–2015), comparing the data of the 7 years that have passed since the introduction of the management protocol (June 2008–June 2015) with the data obtained in the 18 preceding years (May 1990–May 2008), which were published in Anales de Pediatría in 2009.9

The diagnosis of IIH was based on normal neuroimaging findings and transient manifestations of intracranial hypertension. These manifestations consisted of a bulging fontanelle in infants and papilloedema in older children, and could be associated to other symptoms such as vomiting, headache or paralysis of cranial nerve VI, but with eventual resolution of all signs and symptoms.

We excluded cases of intracranial hypertension secondary to trauma, even if the findings of CT were normal, and those with CSF abnormalities, such as cases of encephalitis or viral or bacterial meningitis.

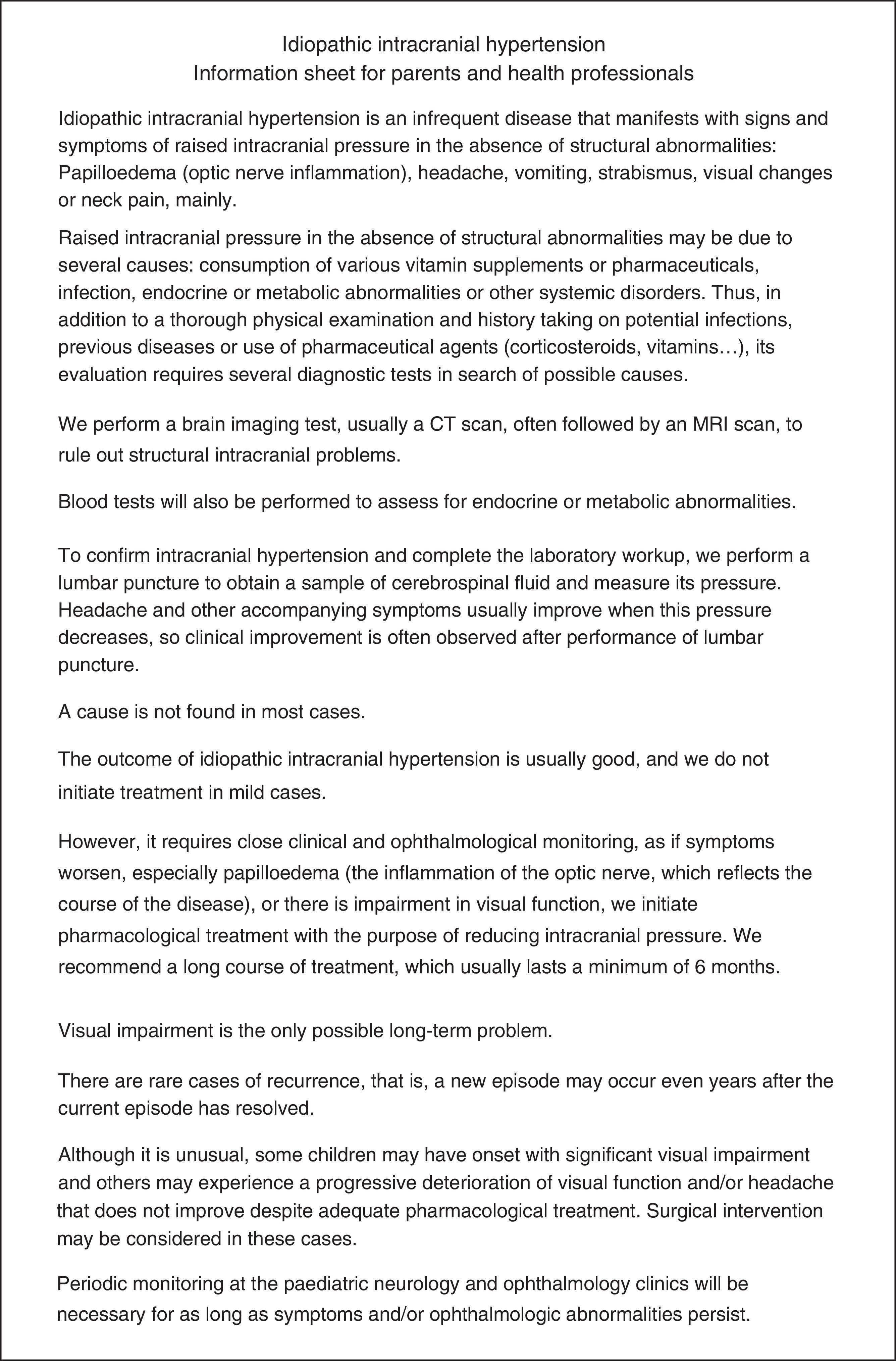

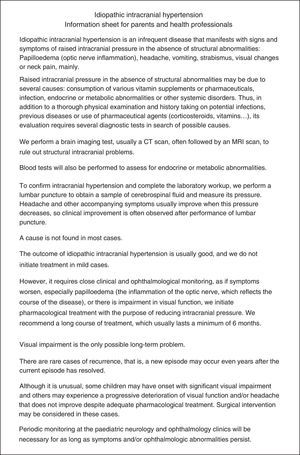

The protocol was introduced in June 2008 and based on the current evidence, and has been revised and updated periodically. The most significant updates took place in 2012 with the introduction of routine quantitative measurement of CSF opening pressure in older children when it became possible to perform it under anaesthesia (until that point it was only assessed qualitatively), and in 2015, when the indications for initiating pharmacological treatment were clearly specified and an information sheet was created to give to parents (Fig. 1).

Our protocol divides children in 2 broad age groups: group I, children with a patent fontanelle, and group II, older children with an already closed fontanelle:

- •

In infants with an open fontanelle, after confirming that the findings of transfontanellar ultrasound are normal, the protocol proposes a watchful waiting approach with close monitoring of clinical manifestations unless there is suspicion of encephalitis or meningitis, in which case a lumbar puncture should be performed on an urgent basis.9 In all other cases, the resolution of signs and symptoms under close monitoring would prevent the performance of other tests that require sedation, such as head MRI. However, in cases with an unfavourable progression or without improvement, a more thorough evaluation with ocular fundus examination, MRI and lumbar puncture should be considered.

- •

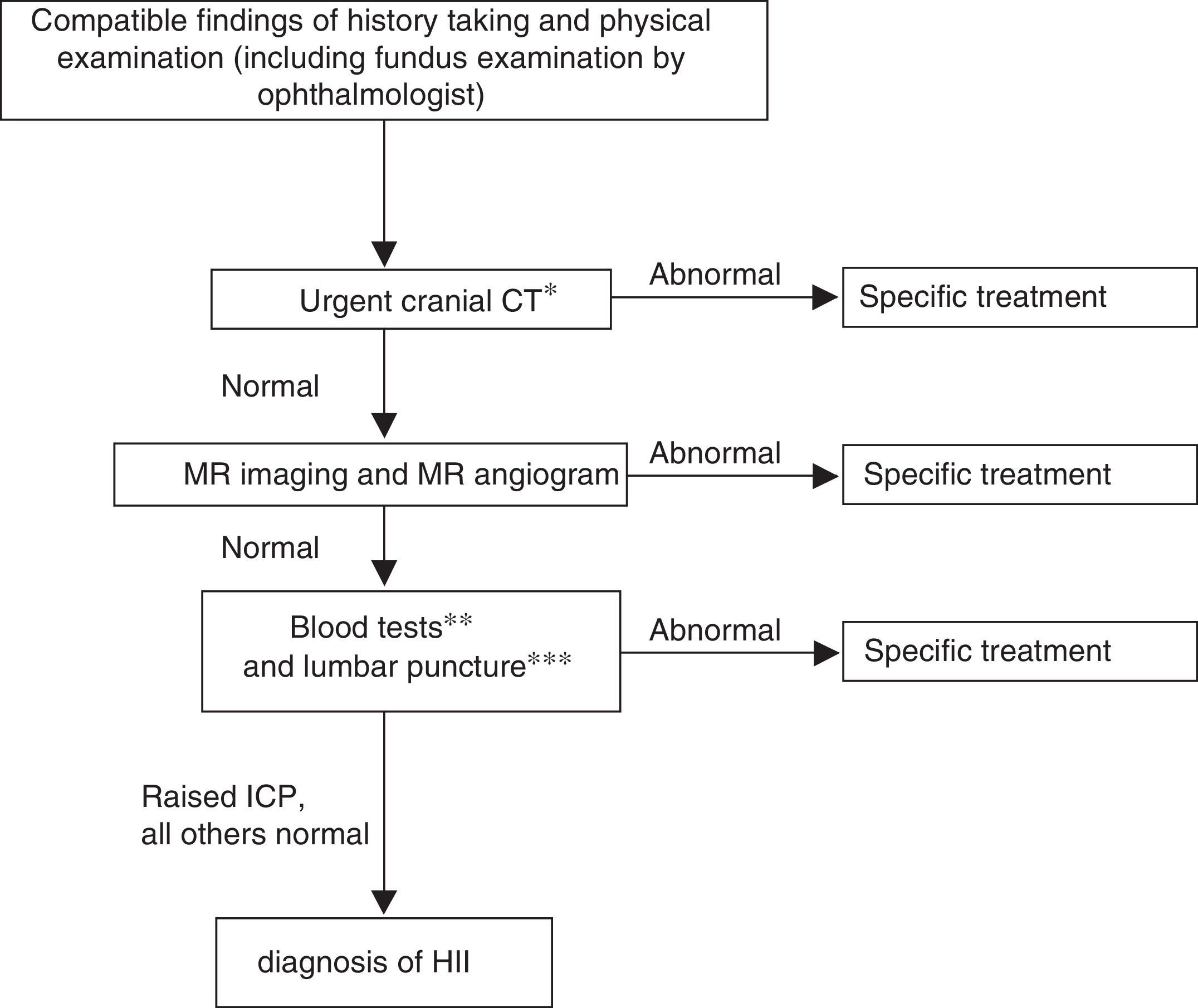

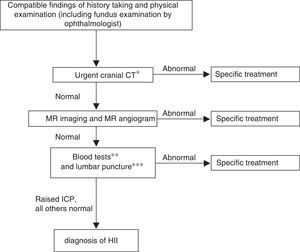

The algorithm for the management of older children with closed cranial sutures is summarised in Fig. 2. After diagnosis, the followup involves close clinical and ophthalmological monitoring (with fundus examination, visual field and visual acuity tests and optical coherence tomography), as ophthalmological outcomes reflect the overall clinical outcome and the patient's response to treatment. Pharmacological treatment is initiated if any of the following circumstances apply (otherwise, the adopted approach is watchful waiting):

Figure 2.Algorithm for the diagnosis of IIH in children with a closed fontanelle.

CT, computed tomography; ICP, intracranial pressure; MR, magnetic resonance.

* Cases of intracranial hypertension call for urgent neuroimaging; head CT is used because it is widely available and quick.

** Blood tests: complete blood count, chemistry panel, CRP, iron metabolism, ionised calcium, thyroid hormones, ACTH and cortisol, coagulation and D-dimer, vitamins A and D, autoimmunity study. Serological blood tests: neurotropic viruses, Mycoplasma, Borrelia, Brucella, supplementing CSF serological tests.

*** In CSF: cell count, biochemistry panel, viral and bacterial culture and CSF serologic testing for neurotropic viruses, Borrelia, Brucella, syphilis.

(0.18MB).

- -

Visual field changes (other than a mild enlargement of the blind spot).

- -

Decreased visual acuity.

- -

Moderate to severe papilloedema (grades 3–5 on the Frisen scale).

- -

Severe headache that is poorly controlled with analgesics.

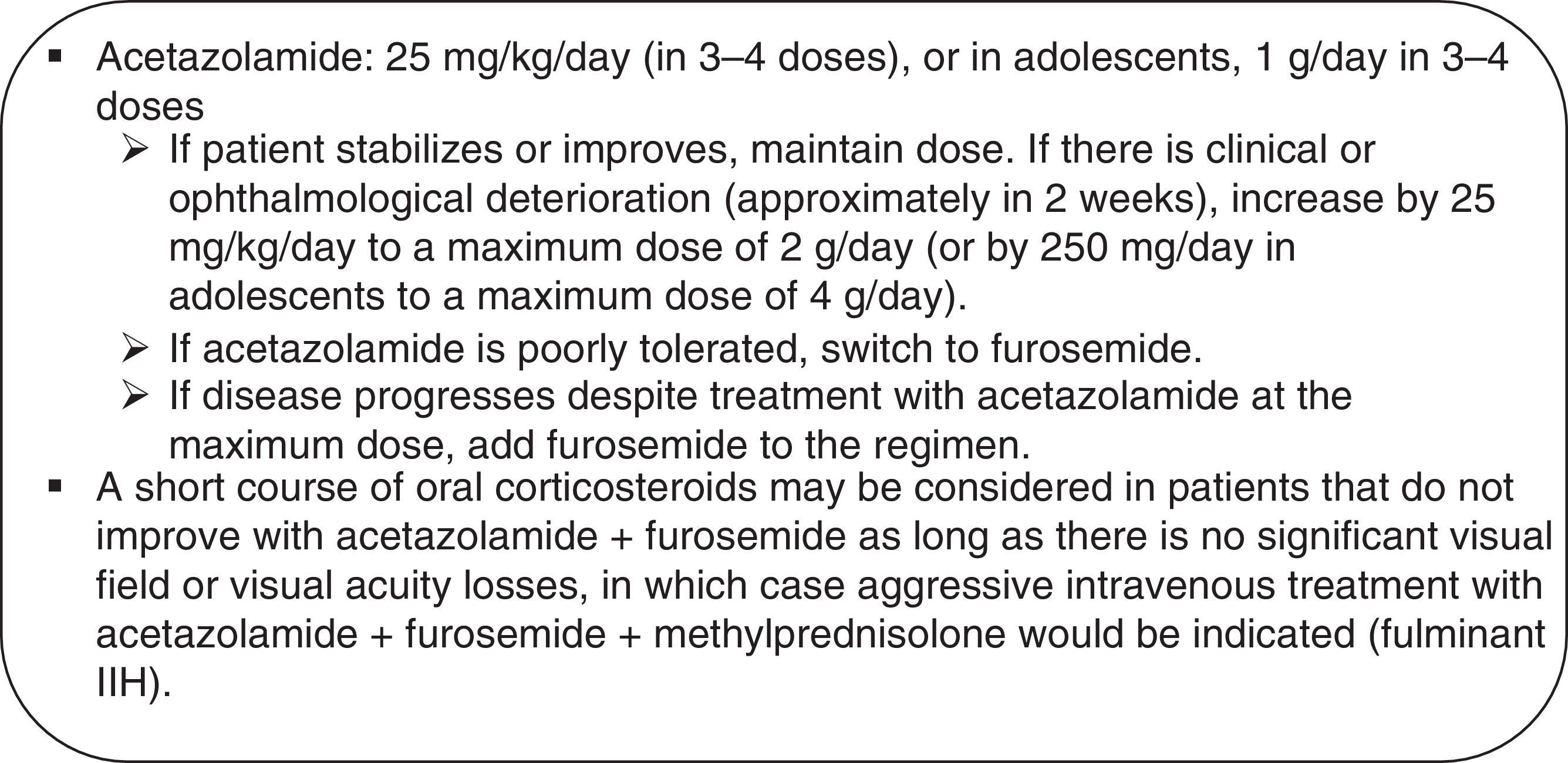

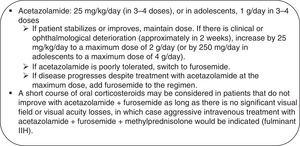

Fig. 3 summarises the treatment algorithm. We reviewed the medical records of patients, collecting data on age, sex, clinical manifestations, diagnostic tests performed, diseases included in differential diagnosis, possible aetiological factors, duration of symptoms before seeking medical care, length of stay, outcomes, time elapsed to resolution of bulging fontanelle or eye fundus changes, and received treatment, if any.

We compared the data for the two time periods—May 1990 to May 2008, and June 2008 to June 2015—and the two age groups.

ResultsIn the 25 years that our paediatric neurology unit has been in operation (1990–2015), a total of 18 865 patients have been evaluated, of which 54 received a diagnosis of IIH: 29 infants and 25 older children.

In the past 7 years there have been 23 new diagnoses of IIH (in 13 infants and 10 older children): group I consisted of 13 infants aged 3–10 months, 8 of them male (62%). The reason for seeking care was bulging fontanelle in all, and all were assessed by transfontanellar ultrasound, the results of which were normal. Two of them underwent urgent lumbar puncture for suspected meningitis, and the results of the CSF analysis were normal. Influenza virus was isolated from nasopharyngeal aspirate samples in 2 patients (type A in 1 and type B in 1). The patient with influenza type A underwent a cranial CT scan after developing seizures. Four eye fundus examinations were requested, and all had normal results.

There was only 1 case in which a potential trigger could not be identified. Potential triggers in other cases included past treatment with prednisolone for bronchitis in 54% (7 cases), viral infection in 4 (including 2 cases of influenza) and acute gastroenteritis with otitis media in 1. One of the patients with IIH that had received steroids to treat bronchitis developed another episode of transient IIH 2 months later in the context of an upper respiratory tract infection.

All patients experienced spontaneous resolution of IIH in a few days without complications, and none had required treatment.

Group ii consisted of 10 patients aged 2–14 years. Two patients were aged 2 years, while the rest were in the 9-to-14 year range. All of them presented with papilloedema. An urgent CT scan was performed in all, followed by head MRI with angiography, the results of which were normal in all except a patient aged 2 years that had cerebral sinus venous thrombosis secondary to otomastoiditis. The CSF cytology was normal in all patients.

We found documentation on the following potential triggers: the venous thrombosis secondary to otomastoiditis in the patient aged 2 years, steroid treatment of a cutaneous angioma in another patient aged 2 years, and growth hormone treatment initiated 4 weeks prior in a patient aged 9 years. We did not find any associated factors in the other 7 patients.

All patients had favourable outcomes free from sequelae. Only 3 patients required pharmacological treatment: acetazolamide in 2 (due to worsening symptoms) and acetazolamide combined with furosemide in 1 (from the time of diagnosis, to treat moderate papilloedema).

One of the patients, a girl aged 10 years that had an episode that resolved spontaneously in 2008, had a recurrence in 2011. We did not find any triggering factors, and on this occasion she was initially treated with acetazolamide for 3 months, but the papilloedema recurred one month after its discontinuation, so treatment was resumed and maintained for 6 months, after which it was discontinued without further problems.

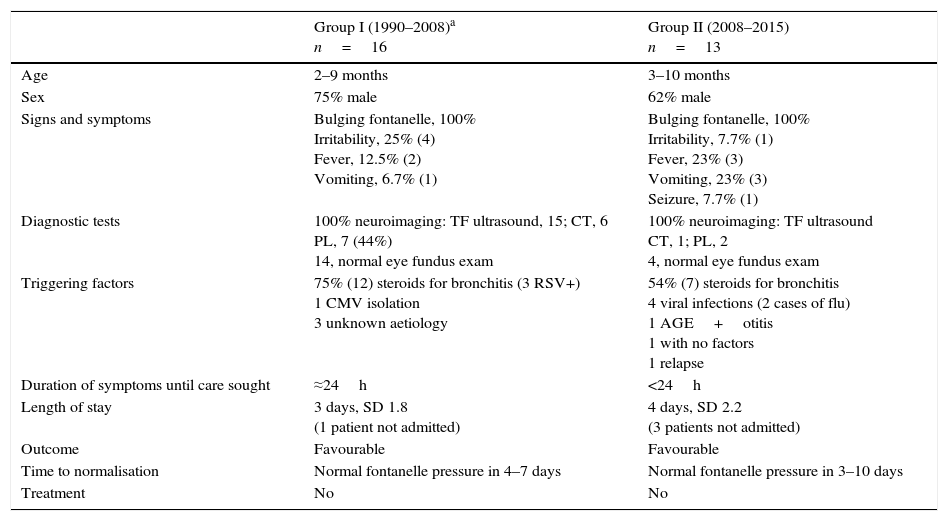

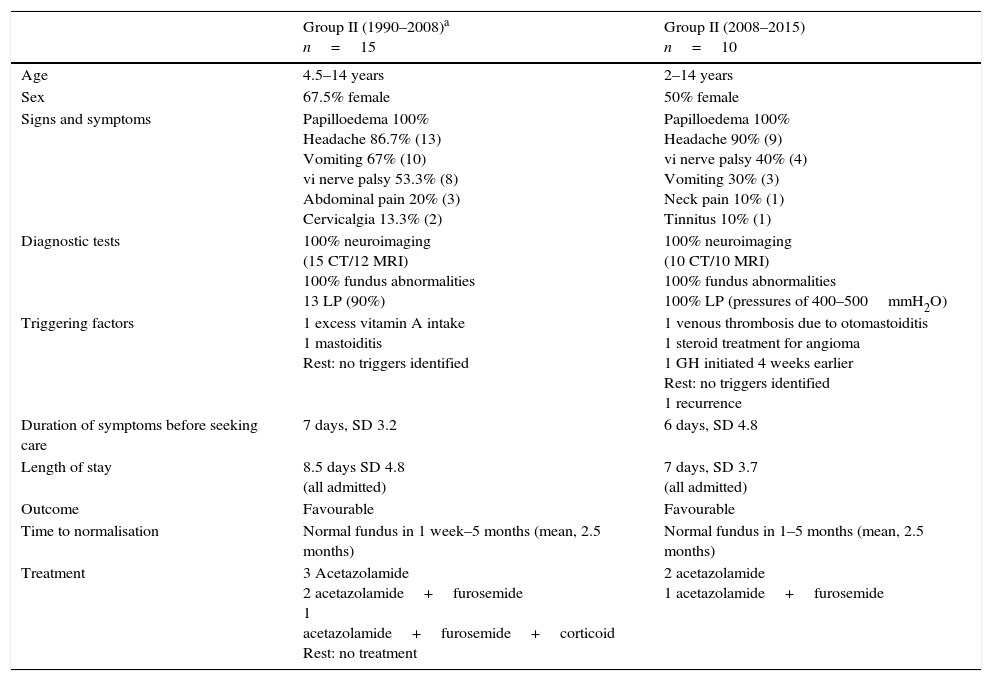

Tables 2 and 3 summarise the main clinical data we have discussed, comparing them with the already published data for the preceding 18 years (An Pediatr [Barc], 2009).9

Comparison of the main clinical features of group I (infants with unclosed fontanelle) in each study period: first 18 years (1990–2008) and last 7 years after introduction of the protocol (2008–2015).

| Group I (1990–2008)a n=16 | Group II (2008–2015) n=13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 2–9 months | 3–10 months |

| Sex | 75% male | 62% male |

| Signs and symptoms | Bulging fontanelle, 100% Irritability, 25% (4) Fever, 12.5% (2) Vomiting, 6.7% (1) | Bulging fontanelle, 100% Irritability, 7.7% (1) Fever, 23% (3) Vomiting, 23% (3) Seizure, 7.7% (1) |

| Diagnostic tests | 100% neuroimaging: TF ultrasound, 15; CT, 6 PL, 7 (44%) 14, normal eye fundus exam | 100% neuroimaging: TF ultrasound CT, 1; PL, 2 4, normal eye fundus exam |

| Triggering factors | 75% (12) steroids for bronchitis (3 RSV+) 1 CMV isolation 3 unknown aetiology | 54% (7) steroids for bronchitis 4 viral infections (2 cases of flu) 1 AGE+otitis 1 with no factors 1 relapse |

| Duration of symptoms until care sought | ≈24h | <24h |

| Length of stay | 3 days, SD 1.8 (1 patient not admitted) | 4 days, SD 2.2 (3 patients not admitted) |

| Outcome | Favourable | Favourable |

| Time to normalisation | Normal fontanelle pressure in 4–7 days | Normal fontanelle pressure in 3–10 days |

| Treatment | No | No |

AGE, acute gastroenteritis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CT, computed tomography; LP, lumbar puncture; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TF, transfontanellar.

Comparison of the main clinical features of group II (older children, closed fontanelle) in each study period: first 18 years (1990–2008) and last 7 years after introduction of the protocol (2008–2015).

| Group II (1990–2008)a n=15 | Group II (2008–2015) n=10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 4.5–14 years | 2–14 years |

| Sex | 67.5% female | 50% female |

| Signs and symptoms | Papilloedema 100% Headache 86.7% (13) Vomiting 67% (10) vi nerve palsy 53.3% (8) Abdominal pain 20% (3) Cervicalgia 13.3% (2) | Papilloedema 100% Headache 90% (9) vi nerve palsy 40% (4) Vomiting 30% (3) Neck pain 10% (1) Tinnitus 10% (1) |

| Diagnostic tests | 100% neuroimaging (15 CT/12 MRI) 100% fundus abnormalities 13 LP (90%) | 100% neuroimaging (10 CT/10 MRI) 100% fundus abnormalities 100% LP (pressures of 400–500mmH2O) |

| Triggering factors | 1 excess vitamin A intake 1 mastoiditis Rest: no triggers identified | 1 venous thrombosis due to otomastoiditis 1 steroid treatment for angioma 1 GH initiated 4 weeks earlier Rest: no triggers identified 1 recurrence |

| Duration of symptoms before seeking care | 7 days, SD 3.2 | 6 days, SD 4.8 |

| Length of stay | 8.5 days SD 4.8 (all admitted) | 7 days, SD 3.7 (all admitted) |

| Outcome | Favourable | Favourable |

| Time to normalisation | Normal fundus in 1 week–5 months (mean, 2.5 months) | Normal fundus in 1–5 months (mean, 2.5 months) |

| Treatment | 3 Acetazolamide 2 acetazolamide+furosemide 1 acetazolamide+furosemide+corticoid Rest: no treatment | 2 acetazolamide 1 acetazolamide+furosemide |

CT, computed tomography; GH, growth hormone; LP, lumbar puncture; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TX, treatment.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is an infrequent disease with potential ophthalmological complications in older children, so it is important that specific protocols for its correct management be established, facilitating diagnostic, follow-up and therapeutic decision-making and reducing the variability in the approaches of physicians involved in the management of these patients.

The described incidence of IIH is of 1–2 cases per 100,000 in habitants, and it is highest in obese women aged 15–44 years.10 There are no specific data on its incidence in the paediatric population, although IIH is most frequently described in female adolescents with overweight, which may be the sole cause.

The pathogenesis of IIH is unknown, and there are many hypotheses that attempt to explain how it develops11: abnormalities in CSF secretion and absorption, cerebral oedema, changes in vasomotor control and cerebral blood flow and venous obstruction, although some authors also consider sinus venous stenosis an entity distinct from IIH.

The scientific literature describes cases of IIH associated with different diseases or drugs. It should be taken into account that these associations correspond to different grades of evidence12:

- •

Clearly associated factors: suspension of steroid therapy, growth hormone (GH) therapy, hypervitaminosis A, obesity or recent weight gain, adrenal insufficiency or hypoparathyroidism.

- •

Published cases with a probable association: treatment with tetracyclines, nitrofurantoin, indometacin, ketoprofen, levothyroxine or vitamin A analogues. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Uraemia.

- •

Possible causes, evidence not rigorous: iron-deficiency anaemia, sarcoidosis, hypovitaminosis A. Treatment with sulphonamides, nalidixic acid, lithium.

- •

Factors cited in the literature but subsequently appearing to have been chance associations, with no evidence of causality: steroid therapy, hyperthyroidism, menarche, pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, menstrual irregularities.

In the paediatric age group, IIH has specific characteristics that differ from those in adults. It could be further divided into 2 age groups with different clinical manifestations and outcomes: children with open cranial sutures and fontanelles, and older children with closed fontanelles.

In infants with open sutures, the most frequent reason for seeking care is a bulging fontanelle, usually detected by the parents, in isolation or possibly associated with irritability. Males predominate in this age band, and triggering factors are often identified, most frequently steroid therapy for bronchitis or upper respiratory tract infections. The outcome is usually good, with IIH resolving spontaneously and without complications in a few days (based in our experience, approximately 1 week), and papilloedema is a rare finding due to the distensibility of the cranial sutures. Given its benign course and outcomes, it is possible to consider close monitoring without additional testing in infants with normal transfontanellar ultrasound findings, unless the disease progresses or fails to improve, is accompanied by fever, or meningitis or meningoencephalitis is suspected. The differential diagnosis should also include shaken baby syndrome, in which retinal bleeding may be found in the fundus examination.

In our experience, there is a predominance of the male sex at early ages, while in older children it is reversed, with a pattern similar to that found in the adult population, in which IIH is more frequent in young women. However, in children it is not frequently associated with excess weight.13 The most frequent reason for seeking care in children with a closed fontanelle is headache associated with vomiting or visual changes (blurred vision due to papilloedema or double vision due to paralysis of cranial nerve VI); other possible but less frequently associated symptoms are neck or abdominal pain. It is not infrequent for a routine eye exam to detect papilloedema in these patients in the absence of any other symptoms.

The diagnosis of IIH may be considered in cases of pseudopapilloedema that may develop in the context of drusen, which are difficult to differentiate initially; both drusen and headache are relatively frequent and can co-occur.14

Other causes of raised intracranial pressure must be ruled out, such as venous thrombosis, subacute or chronic meningoencephalitis, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis or neurocutaneous melanosis.15,16

Unlike what happens in infants, in older children the course of IIH may be longer and potentially severe. This is reflected in the length of stay and the duration of followup, and resolution may take up to 5 months.

The main comorbidity is vision loss, although persistent headaches can also impact quality of life.

There are 2 main goals of treatment: to achieve symptom resolution and preserve visual function in patients while preventing potential sequelae, by reducing intracranial pressure.

If the aetiology of IIH is identified, the key intervention is to discontinue the drug or address the factor that is causing it. Following diagnosis, asymptomatic patients with normal vision and very mild papilloedema can be managed by watchful waiting and the disease may resolve spontaneously (although it may take months). In any case, these patients also require close clinical and ophthalmological monitoring to watch for the development of symptoms or progressive visual impairment requiring pharmacological treatment.

The first-line drug in children is acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor whose mechanism of action is to decrease production of CSF. High doses are required to achieve this effect and may not be well tolerated, in which case treatment can be switched to furosemide or furosemide added to acetazolamide to summate the effects of their two mechanisms of action. Furosemide is a loop diuretic that inhibits sodium reabsorption, resulting in the depletion of extracellular fluid.

Routine or long-term steroid therapy is not indicated. Steroids may be useful as adjuvant treatment in patients with rapidly progressing visual impairment (“malignant” or “fulminant” IIH) while the use of surgery is evaluated. Withdrawal of steroids can cause rebound intracranial hypertension. Furthermore, their side effects (weight gain, fluid retention, hyperglycaemia) may cause problems in these patients.

Topiramate and zonisamide are 2 drugs whose use is being evaluated in adults, as in addition to being carbonic anhydrase inhibitors they provide headache relief and facilitate weight loss. However, there is insufficient evidence to use them as first-line treatment for intracranial hypertension.

No clinical trials have been done that document the effects of different treatments for IIH, and recommendations are based on observational studies with small samples of patients. There are no guidelines specifying whether pharmacological treatment should be initiated from the outset or whether this would offer any benefits, so well-designed and executed trials are needed. Furthermore, there is a high rate of spontaneous resolution.17

Surgery is reserved for children with progressive visual impairment or uncontrolled headache despite adequate pharmacological treatment.18 Invasive procedures performed in IIH may include repeated lumbar punctures (its use is not generally recommended due to its being a painful procedure and its potential complications), placement of a lumboperitoneal or ventriculoperitoneal shunt or optic nerve sheath fenestration (of which there is limited experience in children).19,20 Optic nerve sheath fenestration, or decompression, is reserved for patients with progressive visual impairment and a minimal or no headache, as this method does not lower intracranial pressure. To date, there are no randomised trials in children that compare the efficacy of these surgical interventions.21 Most series provide data on the use of lumboperitoneal shunts, which are less invasive than ventriculoperitoneal shunts and have been shown to improve symptoms and visual function.22,23 However, these techniques are not free of risk and may lead to complications, such as shunt obstruction, repeated system revisions, haemorrhage, infection or low-pressure headache, among others. Fenestration may also be complicated by persistent pupil dilatation from ciliary ganglion injury, ophthalmoplegia and diplopia, retinal artery occlusion or traumatic optic neuropathy.21

Periodical clinical and ophthalmological assessments are required to determine disease severity and make decisions regarding treatment. The progressive withdrawal of pharmacological treatment, when used, should start once the visual function in the patient and the appearance of the optic nerve have stabilised, or when the disease has been in remission for at least 6 months. It is recommended that acetazolamide be tapered off over a minimum of 2 months. Periodic monitoring of patients needs to continue during this stage, when recurrence is not uncommon. Symptoms may recur in 8%–38% of patients that recover from an episode or have been stable for a long time, even years after the initial episode, as was the case of the patient in our series that relapsed 3 years after the first episode. Weight gain has been associated with recurrence in some patients.24

The correct management of these patients requires a well-coordinated multidisciplinary team including paediatric neurologists, ophthalmologists and neurosurgeons.18,21 The introduction of our protocol, approved by all the involved health providers, has allowed us to reduce the variability in the management of IIH, as evinced by the greater consistency of the diagnostic tests ordered in the past few years, and to manage patients based on the latest available scientific evidence through periodic revisions and updates. The establishment of specific guidelines on the timing of initiation of pharmacological treatment and its stepwise dosing has facilitated decision-making, which reduced the number of unnecessary treatments and avoided delays in cases in which treatment was clearly indicated, preventing potential changes in visual function.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare

Please cite this article as: Monge Galindo L, Fernando Martínez R, Fuertes Rodrigo C, Fustero de Miguel D, Pueyo Royo V, García Iñiguez JP, et al. Hipertensión intracraneal idiopática: experiencia en 25 años y protocolo de actuación. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:78–86.

Previous presentation: This study was presented at the XXXIX Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Neurology; May 19–21, 2016; Toledo, Spain.