In clinical practice, it is not rare to encounter situations in which parents and families are asked to leave the child alone with the health care team in rooms full of devices throughout the performance of procedures, which at times may give rise not only to conflicts but, more importantly, emotional sequelae in children or adolescents.

We conducted a narrative review of the literature by searching the digital library of the public health care system of Andalusia for articles concerning the experiences of health care professionals and families with the accompaniment of paediatric patients during health care procedures. We restricted the search to studies published in Spanish or English and conducted in humans.

The review evinced the need to humanise care in order to improve care quality. The need to accompany minors is supported by the evidence from works that have analysed the factors involved in the persistence of these behaviours and attitudes in both professionals and parents. We consider it necessary to develop institutional policies and appoint mediators to compile the statements of different national and international societies, taking into account legal aspects but, above all, the pertinent values from a health care ethics perspective, and in pursuit of the best interests of the child.

En la práctica clínica no es infrecuente observar situaciones asistenciales en los cuales se invita a progenitores y familia a dejar a los menores en soledad junto al equipo asistencial en estancias repletas de tecnología durante la realización de procedimientos, dando lugar en ocasiones a conflictos, pero sobre todo con consecuencias emocionales en los niños o adolescentes.

Se ha realizado una revisión narrativa de la literatura mediante búsqueda bibliográfica en la biblioteca virtual del sistema sanitario público de Andalucía siendo los criterios de inclusión utilizados, estudios que conciernen a las experiencias de profesionales sanitarios y familiares sobre el acompañamiento de la población pediátrica en los procedimientos asistenciales. El resultado de la búsqueda se limitó a estudios en español, inglés y en humanos.

Esta revisión, pone de manifiesto la necesidad de humanizar la asistencia sanitaria para mejorar la calidad de la atención. Se justifica la necesidad de acompañamiento de los menores, a través de trabajos que han analizado los factores que intervienen en la permanencia de estas conductas y actitudes tanto por profesionales como padres. Se recomienda la necesidad de políticas institucionales y figuras mediadoras que recojan las declaraciones de algunas sociedades nacionales e internacionales teniendo en cuenta aspectos legales pero sobre todo los valores en juego desde una ética del cuidado y búsqueda del interés superior del menor.

This request, seemingly simple and polite, carries different meanings and sentiments and elicits feelings that, at times, may give rise to conflict. It is a question that we may be familiar with, having heard it said, or even addressed it ourselves, to parents or relatives (in other words, the group of individuals closely related to the child), in the management of a child with health care needs.

Until recently, this was perceived as appropriate behaviour within a kind and polite relationship in the context of shared decision-making and communication.

Just a few years ago, nobody questioned this prompt. Parents preferred not to witness the “bad experience” of the child and paediatricians and care teams felt at ease in performing a variety of interventions.1

Today, as we pursue the humanization of care delivery to improve the quality of care, is this situation still acceptable? What happens if parents ask to remain with the child? What if the child does not want to be left, on the agreed imposition of others, alone with the health care team in a room full of equipment that feels cold and unfriendly?

To answer these questions, the Committee on Bioethics of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Paediatrics), after reviewing the literature on this issue and its evolution through time, considered the possibility of developing recommendations about the need of children and adolescents to be accompanied during the performance of tests or procedures in their management, and the need for institutional policies and mediators to promote the development of competencies and skills for affective and effective communication, as proposed by the statements of different domestic and international organizations, to facilitate the exchange of information and shared decision-making with a creative and innovative approach, an opportunity for humanizing care in different clinical scenarios and health care procedures.2

To this end, in a deliberative process, we sought to answer the proposed questions through the analysis of the events that have been observed and reflected in different studies and the value conflicts that emerged, with the ultimate purpose of developing guidance adhering to the greatest possible extent to the principles of the ethics of care and in pursuit of the best interests of the child.

MethodsDesignWe conducted a narrative review of the literature by searching the virtual library database of the public health care system of Andalusia, Spain.

SampleInclusion and exclusion criteria, for instance: selection of studies concerning experiences of health care professionals and families with family presence during the performance of procedures in paediatric patients. The population of interest consisted of patients aged 18 years or younger.

Data collectionWe used the following keywords: “acompañamiento” (accompanying), “ética del cuidado” (ethics of care), “familiares” (family members), “menor” (minor), “niños” (children), “reanimación cardiopulmonar” (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), “técnicas” (techniques). We restricted the search to studies conducted in humans published in English or Spanish.

Ethical considerationsThis study did not involve the direct participation of patients nor the collection of patient information.

Background: accompanying and best interests of the childAccompanying/family presenceBefore the development of hospitals, it was families, by default, that cared for the ill at home. It was the creation of hospitals and advances in health care that brought on the restrictions on family presence. Concerns regarding hygiene were the main reason for prohibiting visits.3

In the past century, some human psychology researchers started to write about the deleterious effects of separating mother and child, and attachment theory was formulated in a report prepared for the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1952. However, it was not until the publication of the Platt report in the United Kingdom that a revolution took place in the care of children, going successively from “parental participation” to “collaborative care” to “patient- and family-centred care”, with recommendations given to engage the participation of parents in care delivery, even in resuscitation and invasive procedures, in spite of which there are inconsistencies in how this approach is generally accepted and wide variability in actual practice.4–10

There is evidence of the reservations professionals may feel toward the presence of family members during procedures, the architectural barriers or space limitations and the potential trauma and anxiety that may result from the witnessing of the necessary interventions. Professionals may also feel unease at the possibility of being evaluated or challenged, which heightens the stress.

Different publications have shed light on this situation. An article published in Anales de Pediatría in 2008, “Are parents present during invasive procedures?”, described the practice in 32 hospitals in Spain. In 2012, the changes in culture were assessed in a new publication titled “Has the presence of parents during invasive procedures in the emergency department increased in the last few years?”.11,12

Parents and families could argue that the right of the child to be accompanied is established in article 3 of the European Charter for children in hospital, reflecting the current legal void, with the possible exception of article 18.1 of the Spanish Constitution, guaranteeing the right to personal and family, and aspects regarding confidentiality and personal information contemplated in Law 41/2002 of 14 November on the autonomy of the patient, enumerating patient rights and obligations regarding the access to clinical information by the patient, persons linked to the patient, for family reasons or to the extent that the patient permits.13

The vulnerability of the minor, manifested through emotional needs that are independent of cultural, psychological, spiritual, religious or social differences, underscores the importance of the presence of the family. We must also not forget the decrease in anxiety achieved by having direct access to information and decisions.14

Best interests of the childIn 2001, the working group of the Confederation of European Specialists in Paediatrics defined the best interests of the child considering the child as a unique human individual, holder of rights, deserving of evidence-based care and palliative care to minimise suffering, rejecting intentional end of life and establishing that disability is not a reason to withdraw or withhold treatment.12

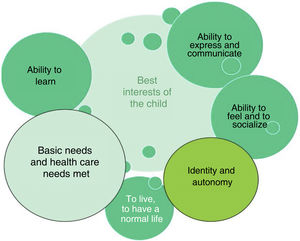

At present, the best interests of the child are defined as seeking to guarantee the child’s future autonomy, freedom to develop a personal identity, ability to meet basic life and health care needs, live a normal life, form relationships, have feelings, learn, communicate and express personal views in the community15–17 (Fig. 1).

Childhood is a social construct concerning a stage of the human lifespan on which values are projected that have evolved over time with the development of the welfare state. Typically, decision-making in pursuit of the best interests of the child involves asking the child’s opinion or considering the ties or values that the child has exhibited in previous decisions or in other contexts.

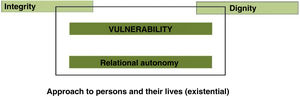

The clinical relationship when a child or adolescent and the family identify a health care need involves values applicable to the different parties involved within the framework of the four principles of bioethics. In Europe, emphasis has been placed on the relational component of autonomy, proposing a model centred on the vulnerability of the human individual (Fig. 2).18

BIOMED II project.

Basic ethical Principles in European bioethics and biolaw (Rendtorff15).

Parents, by default, have the custody of children to protect and care for them. As stipulated in article 154 of the Spanish Civil Code, parental authority will be exercised always for the benefit of the child. If the parents do not interpret the best interests of the child correctly or act to the detriment of the minor (article 158.3), the court can remove custody and place the child under legal guardianship (article 215 and ss.).

The challenge resides in defining what constitutes the best interests of the child and who is to determine it. Historically, it has been assumed that the benefit of the child was an objective matter and had to be pursued by everyone in every proxy decision made in the stead of minors or individuals with disabilities. The responsibility has been placed with the parents, who should be able to choose to or ask to accompany the child during the performance of more or less invasive procedures.

The best interests of the child is an ethical and legal principle that must be taken into account in any proxy or joint decision made in the care of a child, as established in the regulations concerning minors and the law. The latter contemplates the best interests of the child as anything that will benefit the minor, in the broadest possible sense, and not only in material terms, but also social, psychological or moral terms, among other aspects, including anything that may impact the child’s dignity as a person and the safeguarding of the child’s fundamental rights. The best interests of the child must be upheld over any personal preferences of parents, guardians, caregivers, physicians or governing bodies. In this regard, Organic Law 1/1996 on the legal protection of the minor stipulates that “all minors have the right to have their best interests taken as a primary consideration in all actions or decisions that concern them in both the public and private spheres”.

In the case of children that have yet to develop their own value system, decisions are made by proxy. However, the decision-making rights of parents are not absolute; parents may have the initial authority, but not necessarily the last word. If they are not acting for the benefit of the child, society can remove their authority to protect “the best interests” of the minor, understood as follows in the next section.

LegislationOrganic Law 8/2015 on the legal protection of minors, modifying the civil code and the code of civil procedure, and Law 26/2015, amending the system for the protection of minors, introduced the following criteria in relation to the interpretation and application of the principle of the best interests of the child (article 2):

- a)

Upholding the right to life, survival and development of the minor and the fulfilment of the child’s basic needs, material, physical and educational as well as emotional and affective. This applies the principles of nonmaleficence and beneficence.

- b)

Considering the wishes, feelings and views of the minor and the right of the minor to participate to a progressively increasing degree, depending on age, level of maturity, development and personal growth, in the definition of the best interests of the child. This encompasses the principle of autonomy.

- c)

Facilitating that the life and development of the minor unfold in an adequate family environment and free of violence. This applies the principle of justice.

- d)

Protecting the identity, culture, religion, beliefs, sexual orientation and gender identity or language of the minor, and preventing discrimination for these or any other conditions, including disability, to guarantee the harmonious personal growth of the minor. This also applies the principle of autonomy.

Pursuing the best interests of the child requires the family and parents to engage in shared decision-making with children and adolescents as appropriately and sensibly as possible, and to accompany the child in the process of disease and any diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. However, at times there may be parents who do not wish to be present, out of fear or anxiety, or professionals reluctant to their presence, especially in more invasive procedures, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

In such scenarios, different values may come into conflict, such as safety, confidentiality, privacy, care quality, professionalism, relational autonomy and the best interests of the minor.19

Health care professionals may consider that the presence of the family may make interventions longer and hinder the flow of the work, noting the difficulty in informing families. This is compounded by a lack of necessary skills to address the stress of families, in addition to the greater physical and psychological burden imposed by the ongoing interaction with the family, which can be inconvenient and cause interruptions, in addition to the potentially increased risk of nosocomial infection. There is also an underlying impression that the presence of parents complicates teaching, as well as legal concerns.20

In the field of paediatrics, the family should be considered inseparable from the minor in recognition of the right of minors to be accompanied at all times, as a basic need, complementary to care, to which health care facilities and systems need to adapt, as established in the prologue of Decree 246/2005 of 8 November of the Government of Andalusia. Disease places minors in a position of maximum vulnerability, both physical and psychological. The decree specifically devotes one article to the subject (article 8), highlighting the right of minors to be accompanied at all times. The provisions for restricting family presence are very stringent and only contemplate situations in which said presence would hinder care delivery (the rationale usually given for restricting family presence): necessary measures should be taken to avoid any potential negative impact, without forgetting an aspect that is often neglected in the care of children and adolescents, which is privacy during physical examinations or the performance of interventions or procedures. From a culture of consent and trust, it is possible to obtain the information required as long as the minor feels adequately reassured that confidentiality will be safeguarded and decision-making shared. In light of this, disallowing the presence of the parents violates the principles of autonomy and beneficence, even if it does not violate the principle of nonmaleficence in avoiding harm to the child and the family. The absence of parents and/or other family members should be exceptional, for instance, in cases of child abuse or in the care of adolescents who express an unwillingness to be accompanied for privacy concerns or other reasons, thereby safeguarding their right to confidentiality and the protection of personal information, in the absence of a serious threat to their life or physical integrity.

The management of health problems, and specifically family presence or the accompanying of children during procedures, are currently approached avoiding paternalistic attitudes by both health care professionals and families who seek to be more involved in the care of the child, with the goal of providing holistic care that does take into consideration not only technical, but also psychological and emotional aspects.

Bioethical principles of accompaniment and care provision to minorsCare can only be delivered in proximity, and therefore, accompanying the child or adolescent with health care needs is an intrinsic aspect of care delivery that can be construed or defined around three phenomenological notions: phenomena, intentionality and object of knowledge.

- 1

Patient- and family-centred care, associated with effectiveness, functionality and safety, providing care with transparency while safeguarding the dignity of the child.

- 2

The ethics of care concerning educational and relational aspects, integrating a gender perspective, empathy (feeling with the other), avoiding overprotectiveness, undue sacrifice and professional burnout.

- 3

The “whole person care” or biopsychosocial care model with a holistic, spiritual approach that recognises the humanity of the physician, the individuality of the child or adolescent and the importance of the therapeutic relationship. That is, the comprehensive care of the child as a person.

Care can also be understood as a profession or as an act of compassion.21

From the earliest stages of life and childhood, individuals have dignity, a principle that applies to all humans equally. In the context of the ethics of care, dignity and vulnerability must be respected and approached with compassion, solidarity and relational autonomy (responsibility toward others), including the family in the comprehensive sense at the physical, psychological and emotional levels, in a process of humanising health care centred in the person and the person’s life.

Caregiving is the act of assisting another in the process of growing and developing with the ultimate purpose of sustaining life.

No stage of development in human life is as important as childhood, during which it is important to approach the child or adolescent with respect and positive regard as an independent individual, helping them reach their full potential for self-care. This does not result from a need for care or assistance, but rather contributes to autonomy.

Attitudes regarding the presence of the family are based on cultural, religious and economic determinants, among others, and accompaniment is a social construct that has become more prominent, with awareness increasing significantly during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, when it was recognised as a crucial aspect in the intensive care unit (ICU) and neonatal care.22

In the field of paediatric palliative care, there is also evidence of the importance of the family’s presence and participation in different aspects of care (physical and emotional) and in decision-making.23

Ill children feel vulnerable, alone, depersonalized, afraid, uncertain, helpless and in pain, feelings that can be alleviated by the solidarity between patients, the circle of family and friends and the attitude of health care professionals.

Tronto proposed that there are 5 phases in care delivery, as cited by Domínguez et al.,24 summarised in Table 1.

Phases of care.

| Care stage | Responsibility | Action | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| First phase | caring about | Recognising the need of care in others | Attentiveness |

| Second phase | caring for | Taking responsibility to meet that need | Responsibility |

| Third phase | care giving | Performing the actual work of caring and assisting | Technical competence and respect |

| Fourth phase | care receiving | Receiving service or activity | Shared responsibility |

| Fifth phase | caring with | Creating the necessary conditions for care, self-care | Responsibility |

Adapted from Domínguez.24.

Health is the goal of health care. Health recovery or promotion is a life experience tied to wellbeing and caregiving. The issue at hand is not the particular disease at hand or the techniques used in the diagnosis of treatment of the child, the severity of disease, the level of dependence or even the possibility of death; the key issue is assistance to be provided to ensure that the patient goes through those experiences as comfortably as possible and engages in actively in the care delivery process, promoting self-care in the context of everyday living in the family environment.

The care of a child is an activity, an attitude, a commitment, an experience, a social process that goes beyond empathy and affection into dimensions such as the burden of caring and the feelings or worry at the cognitive level. It is a form of social organization that is learnt instinctively, vocational and personal, but also social.25 Caring for and accompanying the patient in the care delivery process should be considered a common good and promoted by institutions with the aim of sharing the responsibility of caregiving and providing care with technical competence and respect, as Tronto described,24 in an act of solidarity.

Recommendation of the Committee on Bioethics of the Asociación Española de PediatríaA child- and family-centred model of care must be promoted, informing and empowering patients and families and involving them in decision-making and care delivery.

Translating the ethics of care to real-world practice beyond the principles and ethics of justice and proceduralism requires the introduction of policies and guidelines that must be adapted to each institution, avoiding power dynamics in health care relationships and the burnout of professionals, approaching care and the accompanying of patients as an activity, a professional task, an attitude and a moral imperative.26,27

In this regard, there are numerous examples at the international level of the implementation of policies and guidelines by institutions such as the Emergency Nurses Association, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, the European Resuscitation Council, the European Federation of Critical Care Nursing associations, the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care or the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR), noting the beneficial impact of offering families, on account of their personal and relational abilities, the opportunity to be present, and the duty of professionals to exhibit sensitivity in these situations.

From the perspective of the ethics of care, it is possible to evolve from a paternalistic perception of care delivery as an individual, private and rational responsibility, in which the child would be left in isolation, to an emotional, relational, compassionate, empowering and solidary activity that takes into account the gender perspective, based on trust, reciprocity and interdependence, made possible by maintaining receptivity,28 with the aim of responding with respectful empathy, an attitude that develops through experience in care delivery.

Thus, there has been a shift from a theoretical-regulatory perspective to an expressive-deliberative approach that promotes compromise and interprets equality as the possibility of understanding the various attitudes of children, adolescents and their families in the context of their daily lives and goals. It combines reason with feelings in a cordial fashion, overcoming the barrier of objectivity and establishing deliberation as a crucial tool.29

For all of the above, the Committee on Bioethics of the AEP recommends the development of guidelines protocols and policies for the accompanying of minors in Spanish health care facilities to uphold a right of minors with beneficial effects and with the help of a professional serving as the intermediary between the child, the family and the health care team and in adherence to the 10 principles listed at the end of this statement (Table 2).

The ten principles on family presence for accompanying minors.

| The ten principles on family presence for accompanying minors in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures |

|---|

| Children have the right to have with them as much as possible during their stay their parents or the person acting in loco parentis (article 3 of European Charter for children in hospital).The protection of the fundamental rights of the child entails safeguarding the child’s dignity and upholding the child’s right to be informed in a developmentally appropriate manner according to the child’s level of comprehension.The presence of parents, family members and/or caregivers may decrease the anxiety of the child and is recognised as a nonpharmacological pain management strategy.The presence of parents or family members accompanying the minor facilitates shared decision-making.Any action by professionals will always be guided by the best interests of the child (Law 8/2015).Proxy decisions made by parents and/or legal guardians of the child or adolescents must always pursue the best interests of the child.The presence of parents or other caregivers accompanying the minor promotes the development of safe practices.Health care facilities must be safe environments for minors (Law 8/2021), upholding children’s rights and promoting a protective physical, psychological and social environment.Professionalism includes the development of care settings and strategies that place the child and family at the centre of care delivery.The routine performance of procedures must not lead professionals to lose touch with the essence of the care delivery act, the child- and family-centred approach to care delivery or the needs and values of the minor and the family. |

Health care professionals must be adequately trained to ensure the holistic support of minors and families guided by these protocols, rooting clinical practice in values and allowing for diversity—cultural, religious, etc.

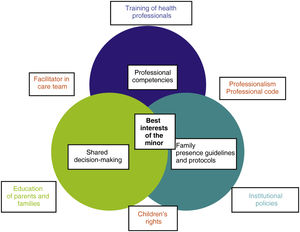

Guidelines and protocols need to detail the competences and responsibilities of each member of the care team, and at least one of them should have the necessary qualification to serve as the professional or family representative or facilitator mediating between paediatric patients and families on one hand and the specialists in the care team, as reflected in Fig. 3.

These institutional policies raise awareness about the positive impact on children of family presence and shared decision-making, which reduces the anxiety of all involved parties and any concerns regarding potential legal ramifications. Thus, we advocate for the development of a professional code which, reflected in the health records, will serve as a model, given the gaps in current law or regulations, as well as strategies for the potential outcomes of the care process, both for families and care teams, to be evaluated periodically, in addition to providing education on the subject.30

FundingNo funding was awarded by any institution for the development of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors representing the Committee on Bioethics of the Asociación Española de Pediatría have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article has been endorsed by the Sociedad Española de Neonatología, Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos de Pediatría, Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología de Pediatría, Sociedad Española de Cuidados Intensivos de Pediatría, Sociedad Española de Pediatría Social and Sociedad Española de Pediatría Hospitalaria.