Tracheal intubation is a frequent procedure in paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) that carries a risk of complications that can increase morbidity and mortality.

Patients and methodsProspective, longitudinal, observational study in patients intubated in a level III PICU between January and December 2020. We analysed the risk factors associated with failed intubation and adverse events.

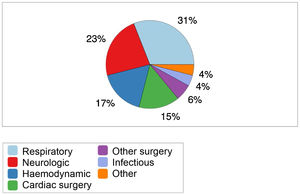

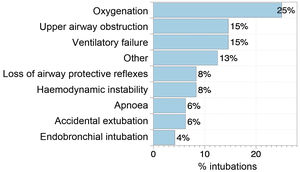

ResultsThe analysis included 48 intubations. The most frequent indication for intubation was hypoxaemic respiratory failure (25%). The first attempt was successful in 60.4% of intubations, without differences between procedures performed by staff physicians and resident physicians (62.5% vs 56.3%; P = .759). Difficulty in bag-mask ventilation was associated with failed intubation in the first attempt (P = .028). Adverse events occurred in 12.5% of intubations, and severe events in 8.3%, including 1 case of cardiac arrest, 2 cases of severe hypotension and 1 of oesophageal intubation with delayed recognition. None of the patients died. Making multiple attempts was significantly associated with adverse events (P < .002). Systematic preparation of the procedure with cognitive aids and role allocation was independently associated with a lower incidence of adverse events.

ConclusionsIn critically ill children, first-attempt intubation failure is common and associated with difficulty in bag-mask ventilation. A significant percentage of intubations may result in serious adverse events. The implementation of intubation protocols could decrease the incidence of adverse events.

La intubación traqueal es un procedimiento frecuente en las unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricos con riesgo de complicaciones que pueden aumentar la morbimortalidad.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio descriptivo y analítico de una cohorte prospectiva incluyendo a los pacientes intubados en una UCIP de tercer nivel entre enero y diciembre de 2020, analizando los factores asociados con el fracaso de intubación y los efectos adversos.

ResultadosSe analizaron 48 intubaciones. La indicación más frecuente fue el fallo respiratorio hipoxémico (25%). El primer intento de intubación fue exitoso en el 60,4%, sin diferencias entre los médicos adjuntos 62,5% y los residentes 56,3%, p = 0,759. La dificultad en la ventilación con bolsa y mascarilla se asoció con el fracaso del primer intento de intubación (p = 0,028). Se objetivaron eventos adversos en un 12,5% de las intubaciones, siendo graves en un 8,3% de los casos, incluyendo una parada cardiorrespiratoria, dos casos de hipotensión grave y una intubación esofágica detectada de forma tardía. Los intentos múltiples de intubación se asociaron significativamente con la aparición de eventos adversos (p < 0,002). La preparación sistemática del procedimiento con ayudas cognitivas y asignación de los papeles del equipo se relacionó de forma independiente con un menor número de eventos adversos.

ConclusionesEl éxito en el primer intento de intubación en niños en estado crítico es bajo y se relaciona con la dificultad de ventilación con bolsa y mascarilla. En un porcentaje significativo pueden presentar efectos adversos graves. La utilización de protocolos puede disminuir el número de eventos adversos.

Tracheal intubation (IT) is one of the most frequent procedures in paediatric intensive care units (PICUs). It is a high-risk technique, especially in critically ill children, who are more likely to have a difficult airway and underlying disease (shock, respiratory failure), with serious adverse events occurring in 20%–40% of cases1–3 that may have an impact on short- and long-term patient outcomes.

Children, especially those aged less than 2 years, are at higher risk of complications of intubation compared to adults due to their particular anatomic characteristics, which make intubation more difficult,4 lesser functional residual capacity and higher oxygen requirements.5,6 Other factors, such as the number of intubation attempts and the experience of the clinician performing the procedure, are also associated with the development of complications.1,5,7,8

The aim of our study was to analyse the factors associated with failed intubation and with the development of different peri-intubation adverse events in the PICU, and to compare our results with those of other studies in the international literature. The secondary objective was to assess the adherence to the local intubation protocol and identify potential areas of improvement.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a prospective, descriptive and inferential cohort study. The sample included all intubations performed in our PICU from January to December 2020. We excluded patients with a tracheostomy or already intubated at the time of admission to the PICU. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the collected data on patient characteristics and adverse events associated with tracheal intubation (TIAEs).

Factors associated with first-pass success.

| Success of first TI attempt, n (%) | Failure of first TI attempt, n (%) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <2 years | 16 (59.3%) | 11 (40.7%) | .853 |

| >2 years | 13 (61.9%) | 8 (38.1%) | |

| Difficult airway | |||

| Yes | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | .63 |

| No | 22 (57.9%) | 16 (42.1%) | |

| Heart disease | |||

| Yes | 15 (75%) | 5 (25%) | .081 |

| No | 14 (50%) | 14 (50%) | |

| Indication of intubation | |||

| Haemodynamic instability | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | .479 |

| Other | 26 (59%) | 18 (41%) | |

| Signs of airway obstruction | |||

| Yes | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | .102 |

| No | 26 (65%) | 14 (35%) | |

| Preoxygenation | |||

| Yes | 27 (60%) | 18 (40%) | .650 |

| No | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Apnoeic oxygenation | |||

| Yes | 5 (45%) | 6 (55%) | .268 |

| No | 20 (64.5%) | 11 (35.5%) | |

| Desaturation | |||

| <10% | 14 (60.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | .830 |

| >10% | 9 (39.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | |

| Physician performing procedure | |||

| Attending physician | 20 (62.5%) | 12 (37.5%) | .676 |

| Medical resident | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (36.8%) | |

| Use of airway cart | |||

| Yes | 26 (60.5%) | 17 (39.5%) | .536 |

| No | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Review of patient history and risk factors | |||

| Yes | 23 (65.7%) | 12 (34.3%) | .085 |

| No | 4 (36.4%) | 7 (63.6%) | |

| Team organization and role assignment | |||

| Yes | 28 (63.6%) | 16 (36.4%) | .06 |

| No | 0 | 3 (100%) | |

| Review of vital signs | |||

| Yes | 27 (60%) | 18 (40%) | .65 |

| No | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Difficult bag-mask ventilation | |||

| Yes | 0 | 5 (100%) | .001 |

| No | 13 (52%) | 12 (48%) | |

| Intubation device | |||

| Direct laryngoscopy | 16 (61.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | .663 |

| Video laryngoscopy | 7 (43.7%) | 9 (56.3%) | |

TI, tracheal intubation.

Adverse events associated with tracheal intubation.

| Serious TIAEs, n (%) | Nonserious TIAEs, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4 (8.3%) | Total | 2 (4.1%) |

| Cardiac arrest with ROSC | 1 (2%) | Unintentional endobronchial intubation | 1 (2%) |

| Cardiac arrest ending in death | 0 (0%) | Immediately recognised oesophageal intubation | 0 (0%) |

| Delayed recognition of oesophageal intubation | 1 (2%) | Vomiting without aspiration | 0 (0%) |

| Vomiting with aspiration of gastric contents | 0 (0%) | Hypertension requiring treatment | 0 (0%) |

| Hypotension requiring intervention | 2 (4%) | Epistaxis | 0 (0%) |

| Laryngospasm | 0 (0%) | Dental or labial trauma | 0 (0%) |

| Malignant hyperthermia | 0 (0%) | Medication error | 0 (0%) |

| Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum | 0 (0%) | Arrythmia | 1 (2%) |

| Direct airway trauma | 0 (0%) | Pain/agitation delaying procedure | 0 (0%) |

ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; TIAE, tracheal intubation adverse event.

Our PICU is a level III unit with 17 beds (11 intensive care beds and 6 intermediate care beds) that admits medical and surgical patients aged 1 month to 17 years, with a substantial percentage corresponding to patients admitted for heart disease or postoperative care after cardiac surgery. The unit is staffed around the clock by paediatric intensive care specialists, second-year residents in paediatrics and fourth-year residents in paediatrics subspecialising in paediatric emergency medicine.

In 2019, before the study, a rapid sequence intubation (RSI) protocol was introduced in the unit, including the creation of a specific airway cart, a verification checklist and a clinical guideline for the management of the difficult airway (Appendix B, 1 and 2). The protocol provides specific instructions on how to prepare the patient for intubation (history-taking, signs of difficult airway, preoxygenation, positioning), prepare the necessary supplies and equipment (intubation medication and devices, ventilator settings), role assignment, the steps of intubation and the difficult airway management algorithm. Several sessions were held to introduce the RSI protocol to the entire staff of the PICU, including multidisciplinary simulation sessions for practical training.

Between January and December 2020, we collected prospective data on variables related to the patient, health care staff, the characteristics of intubation and adverse events. We categorised TIAEs based on their clinical significance as serious and nonserious. Serious TIAEs: cardiac arrest, unrecognized oesophageal intubation, vomiting with aspiration of gastric contents, hypotension requiring intervention (volume expansion or inotropic drugs), laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and direct trauma to the airway. Nonserious TIAEs: unintentional endobronchial intubation, immediately recognized oesophageal, vomiting without aspiration, hypertension requiring treatment, epistaxis, dental or labial trauma, medication error, arrhythmia and pain/agitation requiring additional medication and delaying intubation. For each intubation, we calculated the percentage of adherence to the measures included in the protocol.

The statistical analysis was performed with the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA). We summarised categorical data as percentages, and continuous data as median and interquartile range. We used the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test for the comparison of categorical data and the Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test for the comparison of continuous data. We conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the association of the study variables with first-pass success and the development of adverse events, adjusting for age (≤2 years and >2 years) and the presence of difficult airway, since they are risk factors described in the previous literature.

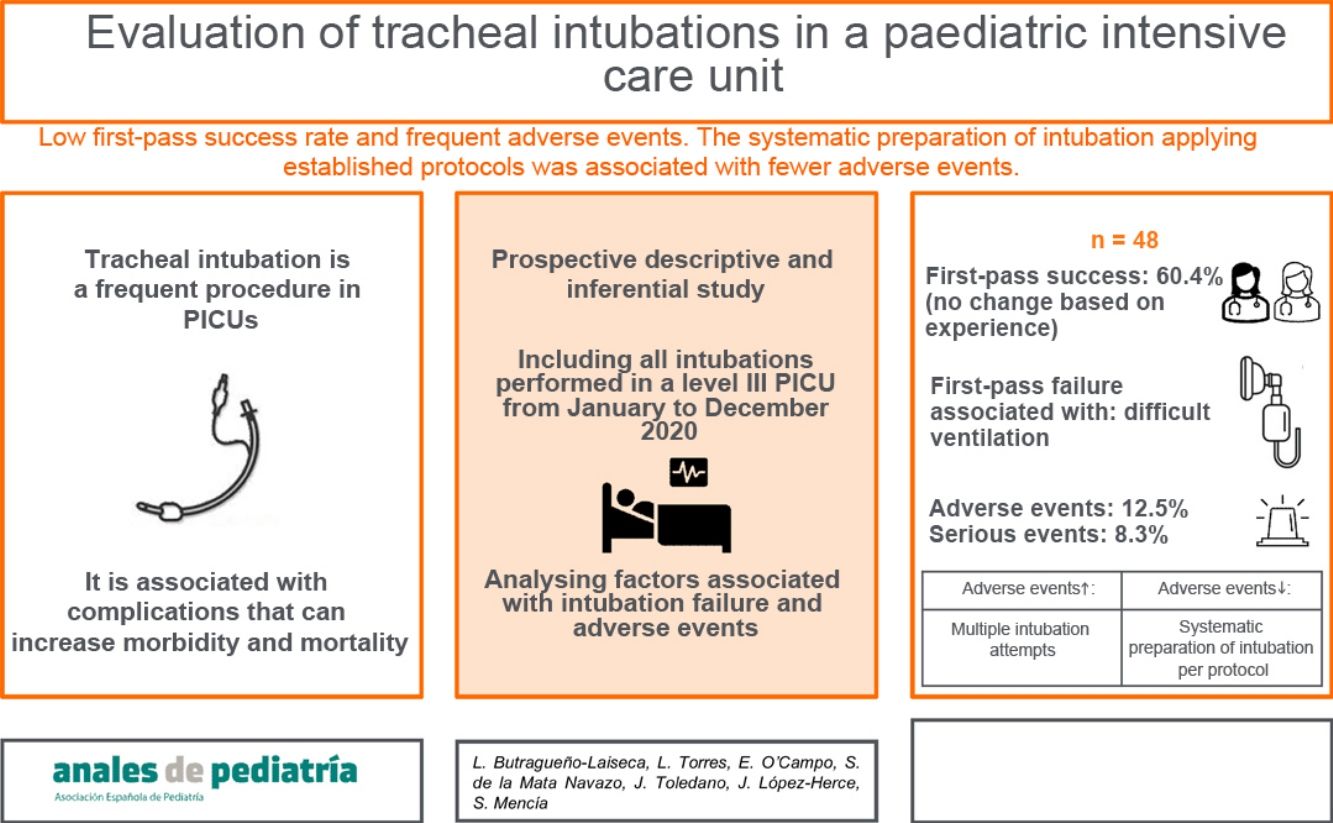

ResultsCharacteristics of intubationIn the year under study, 48 intubations were performed, all of which were included in the analysis. The median patient age was 11 months (interquartile range, 3–62.7) and the median weight 12.5 kg (interquartile range, 5.5–20). Male patients amounted to 70.8% of the sample. In addition, 41.7% (20 patients) had heart disease, which was cyanotic heart disease in 6 cases. The most frequent reasons for admission were respiratory disease and neurologic disease (Fig. 1). Fifty-four percent of intubations were performed in patients not previously intubated, 25% were reintubations and 15% were endotracheal tube (ETT) exchanges. The most frequent indication for TI was respiratory failure (Fig. 2). The ETT was exchanged due to a problem with the size of the tube in one patient, to replace an uncuffed ETT for a cuffed one in another patient, and due to ETT obstruction in 3 patients.

Premedication with atropine was administered in 21 intubations (43.8%). The induction agent used most frequently was etomidate (23 intubations; 48%), followed by midazolam (12 intubations; 25%), ketamine (6 intubations; 12.5%), propofol (2 intubations; 4.2%) and thiopental (1 intubation; 2.1%). The most frequently used analgesic was fentanyl (42 intubations; 87.5%) and the most frequently used muscle relaxant was rocuronium (43 intubations; 90%).

Most intubations were performed by intensive care specialists on staff (35 intubations; 73%), followed by intensive care medical residents (17%), paediatrics medical residents (6%) and anaesthesiologists (2%). The physician that carried out the second attempt was the same one that had carried out the first in 14 cases (74%), a different one in 16%, and an intensive care medical resident in all other cases (10%). The second attempt was successful in 68% of cases, and the reasons for failure were the same as in instances of first-pass failure.

We identified the following risk factors for difficult airway: aged less than 2 years (27 cases; 56%),4 previous history of difficult airway (9 cases; 19%), airway obstruction (7 cases; 15%), facial hypoplasia/retrognathia (6 cases; 12%), Cormack-Lehane grade ii-iv on examination (4 cases; 8%), limitation of neck motion (4 cases; 8%), malformative syndrome (3 cases; 6%) and restricted mouth opening (2 cases; 4%).

Bag-mask ventilation was administered before intubation in 30 of TIs (62.5%), with ventilation difficulties emerging in 5. Apnoeic oxygenation was used during TI in 11 cases. Every patient was intubated through the mouth with a cuffed ETT. Direct laryngoscopy was the method used most frequently in first intubation attempts (27 cases; 56%) and successive attempts, followed by video laryngoscopy with disposable and nondisposable devices. The laryngoscopic view during TI was classified as Cormack-Lehane grade I in 35 cases (73.8%), grade ii in 19% and grade iii in 7.2%. The BURP manoeuvre (back, upward, right and lateral pressure) was used in 42% of first attempts and 47% of second attempts.

Failed intubationIntubation was achieved in 100% of cases, in the first attempt in 60.4% (29 TIs), in the second attempt in 27% (13 TIs) and in the third attempt in 10% (5 TIs). One patient required 5 attempts. We did not find differences in the first-pass success rate between staff physicians and medical residents (Table 1). The most frequent reason for failed TI was difficulty inserting the ETT in the trachea (53%), followed by not visualizing the glottis (37%).

The multivariate analysis did not evince an association between first-pass failure and any of the patient characteristics or indications for intubation, the experience of the physician that performed intubation, health care-related variables or the type of laryngoscopy used, except for difficult bag-mask ventilation (Table 1). In the multivariate analysis adjusted for age and difficult airway, difficult bag-mask ventilation continued to be an independent risk factor for failed intubation (odds ratio, 2.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.097–4.954; P = .028).

Adverse events associated with intubationA total of 6 adverse events were detected in association with intubation (12.5% of TIs). This included the identification of 4 serious TIAEs (8.3%): hypotension requiring intervention (2), cardiac arrest with return of spontaneous circulation (1) and delayed recognition of oesophageal intubation (1) (Table 2). None of the patients died during or as a consequence of the procedure.

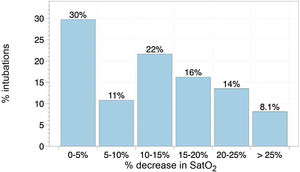

Desaturations during intubation attempts were mostly mild. There was a desaturation of less than 10% relative to the baseline oxygen saturation (SpO2) in 62.2% of first intubation attempts and of 10% or greater in 37.8%, greater than 20% in 21.6% of cases (Fig. 3). We did not find an association between desaturation and the number of intubation attempts (P = .569), the presence of heart disease (P = .769) or the type of physician performing the procedure (P = .572).

In 10% of events (n = 5), there were problems related to supplies during TI, such as specific supplies not being stocked in the airway cart. In one case, there were issues with vital signs monitoring, and in another, lack of team organization and role assignment. No events were documented in association with the readiness or use of intubation drugs.

The univariate analysis revealed that both difficult bag-mask ventilation and multiple intubation attempts were associated with the development of TIAEs (Table 3) and serious TIAEs, although these factors were no longer significant in the multivariate analysis. On the other hand, role assignment was associated with a lower incidence of TIAEs (P = .039); and the use of the airway cart (P = .031), role assignment (P = .016) and the review of the patient’s history and risk factors (P = .037) were associated with a lower incidence of serious TIAEs, an association that persisted in the multivariate analysis adjusted for age and the presence of difficult airway (Table 4).

Factors associated with tracheal intubation adverse events.

| TIAE, n (%) | No TIAE, n (%) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <2 years | 4 (14.8%) | 23 (85.2%) | .683 |

| >2 years | 2 (9.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | |

| Difficult airway | |||

| Yes | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | .678 |

| No | 5 (13.2%) | 33 (86.8%) | |

| Heart disease | |||

| Yes | 1 (5%) | 19 (95%) | .379 |

| No | 5 (17.9%) | 23 (82.1%) | |

| Indication of intubation | |||

| Haemodynamic instability | 0 | 4 (100%) | .575 |

| Other | 6 (13.6%) | 38 (86.4%) | |

| Preoxygenation | |||

| Yes | 6 (13.6%) | 39 (86.7%) | .759 |

| No | 0 | 2 (100%) | |

| Apnoeic oxygenation | |||

| Yes | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | .314 |

| No | 3 (9.7%) | 28 (90.3%) | |

| Desaturation | |||

| <10% | 3 (50%) | 20 (64.5%) | .502 |

| >10% | 3 (50%) | 11 (35.5%) | |

| Physician performing procedure | |||

| Attending physician | 3 (9.4%) | 29 (90.6%) | .451 |

| Medical resident | 3 (18.75%) | 13 (81.25%) | |

| Use of airway cart | |||

| Yes | 4 (9.3%) | 39 (90.7%) | .74 |

| No | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | .031b |

| Review of patient history and risk factors | |||

| Yes | 3 (8.6%) | 32 (91.4%) | .138 |

| No | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | .037b |

| Team organization and role assignment | |||

| Yes | 4 (9%) | 40 (90.9%) | .039 |

| No | 2 (66.6%) | 1 (33.3%) | .016b |

| Review of vital signs | |||

| Yes | 5 (11%) | 40 (89%) | .241 |

| No | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Difficult bag-mask ventilation | |||

| Yes | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) | .001 |

| No | 2 (8%) | 23 (92%) | |

| Intubation device | |||

| Direct laryngoscopy | 4 (15.4%) | 22 (84.6%) | .674 |

| Video laryngoscopy | 2 (9.1%) | 20 (90.9%) | |

| Intubation attempts | |||

| 1 attempt | 0 | 6 (100%) | .002 |

| >1 attempt | 13 (31.6%) | 29 (68.4%) | |

TIAE, adverse event associated with tracheal intubation.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with tracheal intubation adverse events.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of airway cart | 0.059 | (0.004−0.858) | .038 |

| Review of patient history and risk factors | 0.056 | (0.004−0.742) | .029a |

| Team organization and role assignment | 0.016 | (0.001−0.359) | .009a |

| First-pass success | 0.00 | – | .998 |

| Difficult bag-mask ventilation | 0.743 | (0.274−2.017) | .56 |

Factors adjusted for age (≥2 years and <2 years) and difficult airway.

CI, confidence interval.

In most cases, intubation was performed according to the RSI protocol. In more than 90% of instances, the practitioner checked the intubation drugs and the vital signs, the patient received preoxygenation (most through non-invasive ventilation) and roles were assigned to each member of the team. We found the lowest adherence to the protocol for the items concerning the use of the checklist to verify supply and equipment stocks and the assessment of anatomical signs suggestive of difficult airway (Table 5).

Percentage of adherence to different items of the protocol (% of intubations in which the item was carried out).

| Checking intubation drugs | 98% |

| Patient preoxygenation | 94% |

| Review of vital signs | 94% |

| Team task organization and role assignment | 94% |

| Verification of tube placement | 92% |

| Use of airway cart | 90% |

| Checking ventilator settings | 87% |

| Arrangement of supplies on airway cart | 87% |

| Review of patient history | 73% |

| Verifying equipment and supplies with checklist | 67% |

| Assessment of anatomical signs of difficult airway | 53% |

Our study analysed tracheal intubation procedures in a level III PICU, assessing patient, physician and care setting characteristics in relation to successful intubation and adverse events. We found a low first-pass success rate, and did not identify differences based on the experience of the physician performing the procedure, but did find an association with difficult bag-mask ventilation. We found a high incidence of adverse events, which were more frequent in cases of multiple intubation attempts and less frequent when intubation was prepared systematically per the established protocol.

Failed intubationIn our study, the first-pass success rate (60%) was similar to the rates reported in other studies conducted in the PICU setting, including studies of large registries such as the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS).1,5,7 We did not identify any patient characteristic or indication for intubation associated with intubation failure, which was consistent with some previous studies.5 However, studies of larger scale, like a recent report of the NEAR4KIDS registry,7 have found that younger age, a previous history of difficult airway or signs of upper airway obstruction were associated with an increased number of attempts.

The experience of the physician performing the procedure has been identified as a relevant factor that contributes to the first-pass success rate.9–13 In our study, the percentage of first attempts of TI performed by attending physicians was higher compared to other studies, in which medical residents in intensive care are usually the providers responsible for the first attempt.1,5 Since Spain does not have an official curriculum for the paediatric intensive care speciality, medical residents in Spain spend less time training in this subspeciality of paediatrics compared to residents in other countries, which may partly explain our results. However, other studies have also described a decrease in the number of procedures performed by residents in recent years,14 and the development of non-invasive ventilation techniques has also decreased the frequency with which patients require intubation,15 which in turn is reducing frequency with which PICU providers practice intubation in the clinical setting. In addition, given that urgent intubation is frequent in the PICU, the most experienced physician may be tasked with carrying out the procedure to guarantee success and minimise risks to the patient. Paradoxically, in our study, contrary to the findings of the NEAR4KIDS registry,7 we did not find differences in the first-pass success rate based on the experience of the physician performing the procedure, which could be due to selection bias, as attending physicians may have taken charge of intubating unstable patients or patients with suspected difficult airway from the outset, restricting residents to attempting intubation in patients in whom it was less likely to fail.

Intensive care patients admitted to intensive care units often require multiple attempts to achieve intubation.16,17 The incidence of difficult intubation in our study (defined as the need of 3 or more attempts) was slightly higher (12.4%) compared to other studies (7% in the NEAR4KIDS report).5,18

Adherence to the protocolSeveral factors, such as lack of preparation of the patient or the equipment, deviation from protocols and teamwork problems (poor team composition or communication) can also play a role in failed intubation.17,19,20 The use of cognitive aids such as RSI and difficult airway protocols, TI checklists19,21 and training with simulation of TI scenarios, as was done in our unit, have been associated with improved intubation outcomes,22–24 although we were unable to analyse the effect of these measures in our study, as we had not collected data prior to their introduction.

Some studies have found that the use of video laryngoscopy achieves a greater intubation success rate in intensive care units,3,17,25 although others have found contradicting results.26–28 At present, the conventional laryngoscope continues to be the preferred device,29 while the video laryngoscope is considered the first-line device in the case of difficult airway or failed intubation with direct laryngoscopy.3,30 In our study, we did not find a difference in the success rate with the use of conventional versus video laryngoscopy, but the latter has only been introduced recently, and as is the case in every novel technique, training is crucial for its implementation and success, so that structured training programmes need to be developed, including practice on manikins in initial trainings and simulation of clinical scenarios.31

Adverse events associated with intubationAdverse events of TI are frequent, occurring in up to 20% of critically ill paediatric patients,1, and are associated with poorer patient outcomes, longer duration of mechanical ventilation and an increased mortality.32 In our study, we found an incidence of adverse events of 12.5% with an incidence of serious TIAEs of 8.3%, figures that were similar to those observed in other studies.1,32 Several studies have found a higher frequency of TIAEs in mixed intensive care units that provide care to cardiac patients, such as our own, since cardiac patients are at increased risk of adverse events.33–37 In our study, although a high percentage of intubations corresponded to children with heart disease (41.7%), we did not find a greater frequency of TIAEs in this subgroup of patients.

Cardiac arrest can occur in 7% of intubation events and death in 1.6% of intubation events in the cardiac PICU setting.38 In our study, there was one case of cardiac arrest (2%) and none of the patients died from complications of intubation.

Desaturation events are the main complication and most frequent cause of discontinuing intubation.39 Nishisaki et al.1 and Lee et al.7 have reported a frequency of desaturation during intubation (defined as SpO2 < 80%) of 13.5% and 27%, respectively, similar to the frequency found in our study. Desaturation is more frequent and severe in children compared to adults, as children have a lesser functional residual capacity and increased metabolic oxygen demands.6 Desaturation increases with the number of attempts7 and is associated with haemodynamic adverse events (cardiac arrest, hypotension or hypertension requiring intervention and arrhythmia).36,40 Preoxygenation and apnoeic oxygenation strategies may prolong the time to desaturation and facilitate successful intubation in the first attempt.3,17,41,42 However, the current evidence is contradictory as regards the best oxygenation approach.43,44

In our study, neither any of the patient-related factors nor the experience of the physician were associated with TIAEs. In opposition, the NEAR4KIDS registry has identified several factors associated with TIAEs, such as difficult airway and haemodynamic instability.1,7 Some studies have found that intubation performed by medical residents may be associated with an increased incidence of adverse events.1 Branca et al. found a significant increase in the first-pass success rate and decrease in TIAEs with increasing experience in paediatric critical care medicine fellows throughout their training period, which indicates that there is a progressive and significant acquisition of skills.9

As regards the TI procedure, there was a history of difficult bag-mask ventilation in 10% of cases, which was associated with the development of TIAEs in the univariate analysis, in agreement with the findings of the NEAR4KIDS registry.37 The performance of multiple intubation attempts has also been identified as an important factor associated with adverse events.7 Lee et al. found that the incidence of TIAEs increased from 10% in the first attempt to 29% in the second and 38% in the third and subsequent attempts, while the incidence of serious TIAEs also increased from 5% to 8% and 9%, respectively.

The use of cognitive aids and the application of protocols and the airway verification checklist have been associated with a decreased incidence of complications of TI.1,3,8,22,45 In our study, we found considerable adherence to the RSI protocol, and adherence was independently associated with a lower frequency of TIAEs, which supports the use of these aids to improve intubation outcomes in PICUs.

LimitationsThere are several limitations to our study. The data were verified rigorously by the researchers, but were initially self-reported by the physicians that performed the intubations, so there is a risk of recall bias or Hawthorne effect (participants in a study may change their behaviour because they are aware of being observed). On the other hand, our study was conducted in a single centre, in a small sample and in a PICU with a high percentage of patients with complex congenital heart disease, which may limit the generalization of our findings to PICUs with different characteristics. The multivariate analysis may have been affected by the small sample size. Notwithstanding, our study may serve as a model for the implementation of a quality improvement strategy and the analysis of intubation outcomes in the PICU setting.

ConclusionIn critically ill children, TI is associated with a low first-pass success rate and adverse events. Difficult bag-mask ventilation was associated with first-pass failure. The systematic preparation of intubation according to established protocols and with role assignment was associated with a lower incidence of adverse events. The implementation of a continuing education programme with specific RSI protocols, checklists and specific training with simulation could be useful to improve intubation outcomes, but further research is required to confirm it.

FundingNo specific funding or grants have been awarded to this study by any institutions in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.