Infantile haemangiomas are benign tumours produced by the proliferation of endothelial cells of blood vessels, with a high incidence in children under the age of one year (4–10%). It is estimated that 12% of them require treatment. This treatment must be administered according to clinical practice guidelines, expert experience, patient characteristics and parent preferences.

MethodsThe consensus process was performed by using scientific evidence on the diagnosis and treatment of infantile haemangiomas, culled from a systematic review of the literature, together with specialist expert opinions. The recommendations issued were validated by the specialists, who also provided their level of agreement.

ResultsThis document contains recommendations on the classification, associations, complications, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with infantile haemangioma. It also includes action algorithms, and addresses multidisciplinary management and referral criteria between the different specialities involved in the clinical management of this type of patient.

ConclusionsThe recommendations and the diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms of infantile haemangiomas contained in this document are a useful tool for the proper management of these patients.

Los hemangiomas infantiles son tumores benignos producidos por la proliferación de células endoteliales de vasos sanguíneos, con una alta incidencia en niños menores de un año (4–10%) y se estima que un 12% de ellos requiere tratamiento. Dicho tratamiento debe realizarse según las guías de práctica clínica y la experiencia de los especialistas, las características de los pacientes y las preferencias de sus progenitores.

MétodosEl proceso de consenso se realizó utilizando evidencias científicas sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de los hemangiomas infantiles, extraídas mediante una revisión sistemática de la literatura, junto con el juicio experto de los especialistas. Las recomendaciones formuladas fueron validadas por los especialistas, aportando su grado de acuerdo.

ResultadosEl presente documento recoge recomendaciones sobre la clasificación, las asociaciones, las complicaciones, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de los pacientes con hemangioma infantil. Además, se incluyen algoritmos de actuación y se aborda el manejo multidisciplinario y criterios de derivación entre los distintos especialistas que participan en el manejo clínico de este tipo de pacientes.

ConclusionesLas recomendaciones y los algoritmos diagnóstico y terapéutico de los hemangiomas infantiles recogidos en este documentoson una herramienta útil en el manejo adecuado de estos pacientes.

Infantile haemangioma (IH) is the most frequent benign tumour in infancy, and it is produced by the proliferation of endothelial cells of blood vessels. It has an incidence of 4–10% in children under the age of one year.1 Twelve percent (12%) of diagnosed haemangiomas require treatment.1 The predominant locations are the head and neck.2

IH is more frequent in Caucasians and in women. Similarly, there is a greater incidence of IH in premature children and in low-weight.3–5 Some studies relate IH to advanced age of the mother, multiple pregnancy, placenta praevia and pre-eclampsia, although all these factors are related to low weight at birth and to being premature.2,6 As a rule, IH have three evolutive phases: a proliferative phase, in which the lesion grows rapidly, a period of stability in which it ceases to grow, and an involutive phase in which, irrespective of treatment, the colour of the lesion is attenuated and its size diminishes. The duration of each phase depends on the type of IH7: there are some IH with a null or minimal proliferation like the abortive or minimal growth IH7; on the contrary, in certain generally deep and segmental IH the proliferative period extends beyond the first year of life.

The taking of clinical decisions on the treatment of IH must follow clinical practice guidelines and the available scientific evidence, and should also be guided by the experience of specialist physicians, individual patient characteristics and parent preferences. The goal of this consensus is to develop a set of recommendations for: (1) diagnosis and classification of IH, as well as the stratification of haemangiomas in low-, medium- and high-risk groups, (2) paying attention to the early identification of IH subsidiary to treatment and (3) how to perform the treatment. Altogether, this consensus document is intended to be a useful tool for the management of patients with IH.

Material and methodsThis consensus document was drawn up by a multidisciplinary team of 16 specialists from different specialities: Dermatology, Paediatrics, Paediatric Surgery and Cardiology.

The objectives, and an index of contents for the consensus, were defined at the initial meeting in May 2014. Subsequently, an exhaustive bibliographic search was performed, following the criteria used in a systematic review performed in 2011.8 The bibliographic search was carried out by means of the formulation of different clinical questions, using the PICO (Patient/Intervention/Comparator/Outcome) method. The patients included had solitary or multiple IH, strawberry mark, capillary, haemangioma simplex, cavernous or ulcerated IH; interventions included treatment with laser, corticoids, surgery, imiquimod, interferon, bleomycin, vincristine, propranolol; the comparators used were placebo, control with “watch and wait” and other interventions; and the results were defined as the resolution of the IH according to the doctor's and the parents’ evaluation.

Randomised clinical trials (RCT) and reviews published as of March 2011, with the full text available, were prioritised. One hundred and eight (108) publications were identified, of which 35 had the full text. Following the reading of the full text, 16 clinical trials and 12 reviews and evidence reports were chosen (Table S1, supplementary table).

Following the reading of the studies selected, a document was drafted answering each clinical question, and included recommendations. Each specialist could assess the recommendations individually, without maintaining any type of communication or exchange of opinions with other participants of the consensus. Recommendations that obtained unanimity (100% agreement) or consensus (≥80% agreement) were accepted, and those that obtained ≤60% were rejected. The doubtful recommendations (agreement between 61% and 79%) and those regarded as controversial due to the comments made were debated by the specialist panel at a structured, participation-based in situ meeting in October 2014. At the end of the process, a total of 75 recommendations were validated.

ResultsClassification and associationsIH are heterogeneous tumours. Their classification is important to guide in the prognosis, potential complications and treatment. IH can be classified clinically according to two criteria: depth of the affected vessel and shape-distribution pattern2,9 (Table 1).

Classification of infantile haemangioma.

| Depending on vessel depth | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Clinical appearance | Location |

| Superficial | Papules, plaques or crimson tumours with lobulated or smooth surface | Surface dermis |

| Deep | Bluish or normal skin-coloured tumours, sometimes presenting superficial telangiectasias They appear late and tend to proliferate longer | Deep dermis and subcutis |

| Mixed | Double component: (1) superficial, causing the lesion's red colour and (2) deep, providing volume | Dermis and subcutis |

| According to the shape-distribution pattern | |

|---|---|

| Type | Clinical appearance |

| Focal or localised | Rounded, they could be plotted with a compass from a central point |

| Segmental | With geographic borders and following the disposition of embryonic developmental units |

| Undetermined | Intermediate form between focal and segmental |

| Multifocal | Multifocal haemangiomas |

IH, particularly of the head, neck and lumbosacral region, may be associated with underlying structural alterations. In this regard, 2 symptoms typically associated with IH have been described: PHACES syndrome (Posterior fossa malformations/Hemangiomas/Arterial anomalies/Cardiac defects/Eye abnormalities/Sternal cleft/Supraumbilical raphe syndrome) (OMIM #606519) describes alterations associated with large facial and segmental haemangiomas whose diagnostic criteria were established in 2009.10 Between 20% and 31% of large and segmental IH of the face are known to be associated with PHACES syndrome.11 PELVIS syndrome (Perineal hemangioma/External genitalia malformations/Lipomyelomeningocele/Vesicorenal abnormalities/Imperforate anus/Skin tag), also known as SACRAL or LUMBAR syndrome, has been proposed to refer to the group of alterations associated with large or segmental IH in the lumbosacral region.12,13Table 2 presents the anomalies that may be presented by patients with PHACES and PELVIS/SACRAL/LUMBAR syndrome.

Infantile haemangioma associations.

| Alterations associated with PHACES syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Cerebral | Structural: Posterior fossa anomalies, Dandy-Walker syndrome, hypoplasia or agenesis of the cerebellum and supratentorial abnormalities Vascular: Dysgenesias, abnormal course, stricture or non-visible cerebral vessels Sequelae: cerebrovascular accidents, hemiparesis, seizures, psychomotor delay, migraines |

| Cardiovascular | Aberrant origin of the subclavian artery, coarctation of the aorta |

| Cardiac defects | Interventricular septal defects, pulmonary stenosis, anomalous pulmonary veins |

| Ocular abnormalities | Alterations of retinal vessels, optic atrophy, iris hypoplasia, congenital cataracts, coloboma of the crystalline lens, optic disc alterations and persistence of foetal retinal vasculature |

| Sternal cleft or supraumblical raphe | Sternal malformations, supraumblical raphe, hypopigmented macules, presternal dimples and omphalocele |

| Other associations | Hypopituitarism, growth hormone deficit, hypothyroidism, sensorineural hearing loss |

| Alterations associated with PELVIS/SACRAL/LUMBAR syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Spinal dysraphia | Lipomeningocele, tethered spinal cord, intramedullary lipoma |

| Perineal | imperforate anus, anterior ectopic anus, rectoperineal fistula |

| Genitourinary | Single kidney, vesicoureteral reflux, urinary bladder alterations, ambiguous external genitalia, bifid scrotum, vulvar hyper- or hypotrophy |

PHACES: Posterior fossa malformations/Hemangiomas/Arterial anomalies/Cardiac defects/Eye abnormalities/Sternal cleft/Supraumbilical raphe síndrome.

PELVIS: inglés Perineal hemangioma/External genitalia malformations/Lipomyelomeningocele/Vesicorenal abnormalities/Imperforate anus/Skin tag.

Most IH are diagnosed by means of a physical examination and the lesion's evolutive history.

The medical history should collect data related to pregnancy, the perinatal period and the lesion's evolutive details. Between 30% and 50% of IH present a precursor lesion in the form of a pink or telangiectasia-like macule, which may be confused with capillary malformations, nevus anemicus, hypochromic nevus or traumatism.

Differential diagnosisA differential diagnosis must be performed of deep IH with nasal gliomas, dermoid cysts, infantile myofibromatosis, neuroblastomas, plexiform neurofibromas, pilomatricomas, lipomas and other sarcomas, although imaging techniques usually suffice to make the diagnosis.14,15 In turn, multifocal IH must be distinguished from multifocal lymphangioendotheliomatosis,16 Bean syndrome or Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Finally, superficial IH may be confused with tufted haemangiomas and Kaposiform haemangioendotheliomas, hemangiopericytomas or angiosarcomas.

Diagnosis of the extentThe internal involvement of an IH need not be anatomically related to the haemangioma of skin although segmental or large haemangiomas have a greater risk of association with internal haemangiomas.17 In this regard, the existence of 5 or more haemangiomas of skin should constitute justified cause to perform an abdominal ultrasound.18 Visceral IH are usually asymptomatic and may appear in different sites, being the liver the most frequent location. However, on certain occasions, clinical symptoms may assist in the diagnosis of internal haemangiomas: stridor, cough or loss of voice in airway IH; intestinal haemorrhage in gastrointestinal tract IH; heart failure, respiratory distress or signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism in large or multifocal hepatic haemangiomas.

Diagnostic techniquesImaging studies can be very useful in making a correct diagnosis, although there is no consensus about when they should be indicated in order to determine the internal extent of an IH. Generally speaking, analytical tests are not of great help in the diagnosis of IH.

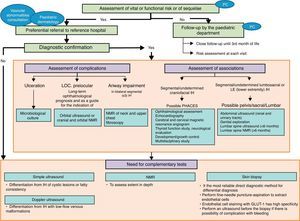

Fig. 1 displays the recommendations formulated with regard to the diagnosis of IH in the form of an algorithm.

Infantile haemangioma diagnostic algorithm. PC: primary care; IH: infantile haemangioma; LOC: location; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance, PHACES: posterior fossa malformations/hemangiomas/arterial anomalies/cardiac defects/eye abnormalities/sternal cleft/supraumbilical raphe síndrome. PELVIS: inglés Perineal hemangioma/External genitalia malformations/Lipomyelomeningocele/Vesicorenal abnormalities/Imperforate anus/Skin tag.

Most IH have a predictable clinical course, tending towards total or partial spontaneous involution. However, certain IH may become complicated at local level, causing aesthetic sequelae or compromising vital organs.19 In this regard, the classification of IH according to the risk of sequelae or complications (Table 3) is useful.

Classification of infantile haemangiomas according to the risk of sequelae and complications.

| Type of haemangioma | Risk |

|---|---|

| High-risk | |

| Segmental haemangiomas in any location on the face and diameter >5cm | PHACES syndrome |

| Segmental haemangiomas in the chin area and diameter >5cm | PHACES syndrome and infantile haemangioma in the airway |

| Infantile haemangiomas lumbosacral area and diameter >5cm | PELVIS |

| Mixed or thick superficial haemangiomas on tip of the nose, glabella, philtrum, centre of cheek and diameter >1.5cm | Aesthetic impairment |

| Haemangiomas that deform the lip contour | Aesthetic impairment |

| Mixed or deep periocular haemangiomas | Functional risk |

| Haemangiomas in the ear canal | Functional risk |

| Mixed or thick superficial haemangiomas on the mammary areola | Aesthetic impairment |

| Ulcerated haemangiomas | Pain and risk of scaring |

| Intermediate risk | |

|---|---|

| Haemangioma in other unmentioned face locations | Risk of aesthetic impairment |

| Large haemangiomas on the hands (3–5cm diameter) | Risk of aesthetic impairment |

| Haemangiomas in folds | Risk of ulceration |

| Segmental haemangiomas in any location and diameter >5cm | Risk of ulceration, associated arterial alterations and aesthetic impairment |

| Pedunculated haemangiomas | Risk of aesthetic impairment |

| Low risk |

|---|

| Superficial haemangiomas in other locations |

| Deep haemangiomas in other locations |

| Small mixed haemangiomas |

Adapted from Luu et al.39

PHACES: Posterior fossa malformations/Hemangiomas/Arterial anomalies/Cardiac defects/Eye abnormalities/Sternal cleft/Supraumbilical raphe síndrome. PELVIS: inglés Perineal hemangioma/External genitalia malformations/Lipomyelomeningocele/Vesicorenal abnormalities/Imperforate anus/Skin tag.

Local complications include ulceration, infection, bleeding and pain. Ulceration is the most frequent complication being predisposing factors: size of the IH, segmental distribution, the appearance of a superficial greyish surface area, and location in regions of sustained friction and humidity.14,20

IH located in the periorbital area may produce astigmatism, strabismus and the obstruction of the visual axis presenting amblyopia and the risk of permanent loss of sight. Other IH, particularly bilateral ones and located in the chin, present a high risk of affecting the airways.

The risk of psychological impairment deserves special attention due to the aesthetic sequelae of IH, particularly in IH located in visible areas. Even though the future appearance of a haemangioma is difficult to predict, superficial IH do not usually cause sequelae, whereas mixed and voluminous IH tend to leave residual fibroadipose tissue.21

Location, size, complications, treatment or association with other conditions may have a negative impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. A recent study reported no significant differences in the quality of life indices of patients with and without IH,22 although other studies indicate that children between 3 and 7 years could be the most susceptible in terms of impact on self-esteem.23 Recently, a specific instrument has been developed for the assessment of the impact of IH on the quality of life of patients and their families consisting in a survey of 29 questions divided in four scales that asses the morbidity caused by IH, its consequences on the child social interactions, and the impact on the family emotional and psychosocial functioning.24

Comprehensive treatmentThe protocolisation as to when and how an IH should be treated is complex. Not all haemangiomas of the same size and location undergo the same clinical evolution; and the psychological impact of the IH on the child and the family cannot be extrapolated between patients with the same tumour.

Even so, there are absolute indications for the treatment of IH: (1) Potentially lethal IH or those that endanger functional capacity, (2) Ulcerated IH with pain and/or absence of response to basic wound-care measures and (3) IH with risk of permanent scarring or disfigurement.

Until the year 2008, oral corticoids were the treatment of choice for complicated IH, despite their side effects at high doses and the absence of response to treatment in one third of the cases.

Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for IH and is the only one that has been approved for this indication.

Propranolol's efficacy is greater than that of any other treatment from the onset and at any location of the body.25 Moreover, a positive effect on the quality of life of patients with IH and their families has been described.26 The approved dose of propranolol is 3mg/kg, which has shown greater efficacy than 1mg/kg, with no increase in toxicity.25 The exact toxic doses of propranolol are unknown, but children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have been treated with doses of 5mg/kg/day, with low incidence of complications.27 The intake of doses 2 or 3 times the therapeutic dose may be life-threatening for patients.28

There is certain controversy as to whether the administration of propranolol in patients with PHACES syndrome with alterations of the big intracranial vessels and aorta coartation for the potential risk of cerebral ischaemia that may cause hypotension. For this reason, at least a cardiological study should be performed in these patients, and ideally a magnetic resonance angiogram before treatment with propranolol is initiated. In cases where the magnetic resonance angiogram with sedation is not advised, starting treatment with lower-dose propranolol and slowly scaling is recommended.

Other beta-blockers have also demonstrated their efficacy (acebutolol,29 atenolol30 and nadolol31), although they have shown no significant advantages over propranolol.

The side effects of beta-blocking drugs are well known28: (1) cardiovascular (bradycardia and hypotension), (2) bronchial (reduction in bronchodilatory tone and increased resistance of the medium-sized airways), (3) metabolic32 (hypoglycemia), (4) renal (reduction in glomerular filtration) and (5) central nervous system33 (possible impairment of memory, sleep quality, mood and psychomotor functions).

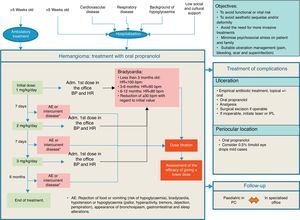

The recommendations issued by the specialists for the treatment of IH, the use of propranolol and the prevention of its adverse effects are detailed in Table 4. Similarly, an action algorithm is presented for the treatment of IH (Fig. 2).

Recommendations in the treatment of infantile haemangioma.

| Beginning of treatment (between 5 weeks and 5 months of life (age corrected for prematures)*: • Perform a health history and a clinical exploration to rule out cardiovascular and respiratory problems • Perform an ECG if: - HR is <100bpm in infants under 3 months, <90bpm between 3 and 6 months and <80bpm between 6 and 12 months - There is a familial history of congenital heart disease or arrhythmias, maternal history of connective tissue disease, personal history of arrhythmia or if an arrhythmia is detected during the exploration • An exhaustive cardiological evaluation is not regarded as necessary in symptom-free patients without previous cardiac disease |

| Propranolol: • Propranolol treatment should be initiated at 1mg/kg/day administered in 2 doses. Dosage should be increased by 1mg/kg/day weekly until reaching the recommended dosage in three weeks • The recommended therapeutic dose of propranolol is 3mg/kg/day, given in two separate 1.5-mg/kg doses, in the morning and late afternoon, with a minimum interval of 9hours between both30 • It must be given over a period of 6 months, with clinical follow-up and dose re-titration based on weight at least every month. In some patients the treatment should last for more than 12 months • It should be given while the child is being fed or immediately afterwards in order to avoid the risk of hypoglycaemia • Administer directly to the mouth of the child, using a dosing syringe for oral use, or else diluted in a small amount of baby milk or juice (5ml in children <5kg and 15ml in children >5kg). It can be given in the bottle with milk, although it is advisable not to add it to a full bottle. Use within the following 2h • If the child vomits, refuses to feed or to take all the medicine, omit the dose and do not give another one until the next scheduled dose • Discontinuation of treatment does not require a progressive dose reduction, and if the symptoms relapse following treatment discontinuation it may be resumed in the same conditions • Ambulatory observation is deemed prudent following the first administration at each change of dose, monitoring pre-administration BP and HR and every 60min until 2h have elapsed with a view to ruling out cardiovascular complications • During propranolol treatment prolonged fasting periods should be avoided, and if necessary because of the need for surgery or because the baby is not feeding well the treatment should be stopped temporally. Make sure the child eats something following the administration of the drug • Serial capillary blood-sugar monitoring is only required in insulin-dependent diabetic patients. In the rest of the patients, it will suffice to train the parents in the early recognition of the signs associated with hypoglycaemia |

HR: heart rate, bpm: beats per minute, ECG: electrocardiogram, BP: blood pressure.

Another effective systemic treatment for the treatment of IH is interferon-alpha, although it can cause spastic diplegia in infants.34 Timolol maleate, in topical form, has shown effectivity in superficial lesions,35 without presenting significant side effects.36 Topical corticoids and 5% imiquimod have also been used anecdotally. Finally, PDGF (Platelet Derived Growth Factor) appears to be useful in the topical treatment of ulcerated IH,37 although it might be associated with a greater incidence of cancer (Table 5).

Reasons for referral to the primary care paediatrician.

| Type of IH | Reason for referral to the dermatologist |

|---|---|

| Large facial segmental | Risk of associations |

| Involving the tip of the nose, pinna, glabella and central area of the face in general | Aesthetic impairment |

| Periorbital and retrobulbar | Visual impairment |

| Labial and perioral | Feeding difficulties and tendency to ulceration and to producing permanent deformities |

| Lumbosacral area | Risk of associations |

| Perineum, axilla, neck | Risk of ulceration |

| Multifocal with 5 or more lesions | Risk of hepatic or visceral affectation. |

| Ulcerated IH | Treatment of pain and ulcerations |

| Superficial, highly raised with abrupt vertical border, pedunculated | Risk of permanent deformity |

Treatment of IH with laser is indicated in three cases: treatment of the proliferative phase, albeit not as a first option, treatment of ulcerated IH, and treatment of telangiectasias and residual textural alterations.

Surgery is fundamentally indicated in the treatment of sequelae, although thanks to propranolol, the sequelae that require surgical correction have diminished considerably. Surgery may be the first treatment option in pedunculated IH, IH with painful and persistent ulceration, compression of the eyeball and progressive facial deformity. Once the surgical indication has been established, the child should be operated preferably before the age of four years.

Finally, the psychological repercussion of a haemangioma on the family environment is significant and may require specialised psychological care. Proper treatment of IH can avoid subsequent risk behaviours, such as social isolation, depression or anxiety.

Multidisciplinary management and the role of the Primary Care PaediatricianThe Primary Care Paediatrician (PCP) is a medical professional who is closer and more accessible to the child and the family. Their role is fundamental in the early diagnosis and referral to the dermatologist of IH susceptible of treatment, ideally within the first 3 months of life. Referral circuits between the two healthcare levels must be flexible and waiting times short within at least 15–21 days at most. In this regard, the shared use of virtual resources (telemedicine with photographic control of evolution) may greatly facilitate the referral of patients and treatment follow-up.

Treatment with propranolol may be initiated at ambulatory level, provided that the resources required to solve possible post-administration complications are available. The dermatologist may decide, together with the PCP, for the beginning of treatment and dose titration to be performed in the PCP's office.

The monitoring of patients receiving oral treatment with propranolol must be carried out in Primary Care, hence the PCP must be conversant with the relevant treatment aspects: dose, duration, possible side effects and how to proceed if they occur, and in the event of intercurrent symptoms that may affect treatment.

The PCP should inform the parents and caregivers of the possible side effects of propranolol. This information should be conveyed in a simple and understandable way, and may be reinforced by the use of written material.

The formation of multidisciplinary teams in hospitals for vascular anomalies care is important in the management of IH patients and in particular is necessary for the diagnosis and management of patients with complex haemangiomas.38 The multidisciplinary team may be comprised of different specialists: dermatologists, paediatricians, cardiologists, anatomical pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, neurologists and neurosurgeons. Although there is no universally accepted guide for the intrahospital management of IH,19,39 the following steps are suggested:

- 1.

Confirmation of the clinical diagnosis, usually in the dermatology department.

- 2.

Assessment of the risk of functional impairment, aesthetic impairment, associated anomalies, complications and sequelae.

- 3.

Consultations with paediatricians: otolaryngologists in chin-area IH; surgeon for pedunculated IH and for the evaluation of aesthetic sequelae; radiologist, neurologist and neurosurgeon in suspected PHACES or LUMBAR syndrome; ophthalmologist in IH with risk of visual impairment.

- 4.

Treatment decision in agreement with the specialists involved. Start in day hospital or hospitalisation, as necessary. Consultation with a paediatrician or a cardiologist in the event of side effects.

- 5.

Scheduling of clinical controls in dermatology and the outpatient departments of the other specialities involved. Photographic record for control of evolution and response to treatment.

- 6.

Periodic meetings of the multidisciplinary team to address complex cases of IH.

The taking of therapeutic decisions in IH must be based on the available scientific evidence and experience of the specialists. For this purpose, the Spanish IH Consensus and the recommendations and the algorithms it contains constitute a useful tool in the suitable management of patients with IH.

FundingThe conducting of the consensus, as well as the preparation of this article, have been funded by Laboratorios Pierre Fabre Ibérica S.A.

Please cite this article as: Torres EB, Wittel JB, Van EssoArbolave DL, Bosch MIF, Sanz ÁC, Laguna RDL, et al. Consenso español sobre el hemangioma infantil. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;85:256–265.