After reviewing the best available scientific information, CAV-AEP publishes their new recommendations to protect pregnant women, children and adolescents living in Spain through vaccination.

The same recommendations as the previous year regarding hexavalent vaccines, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine of 13 serotypes, booster with tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis and inactivated poliomyelitis (Tdpa-IPV) at 6 years and with tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (Tdpa) at 12–14 years and pregnant women from week 27 (from week 20 if there is a high risk of preterm delivery).

Also with rotavirus, tetraantigenic meningococcal B (2+1), meningococcal quadrivalent (MenACWY), MMR, varicella and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, for both genders.

As novelties this year the CAV-AEP recommends:

Influenza vaccination from 6 to 59 months of age whenever feasible and does not harm the vaccination program aimed at people at higher risk.

According to official national recommendations, the CAV-AEP recommends the systematic use of COVID mRNA vaccines since 5 years old.

Tras la revisión de la mejor información científica disponible, el CAV-AEP publica las nuevas recomendaciones para proteger con vacunas a las embarazadas, los niños y los adolescentes residentes en España.

Se mantienen las mismas recomendaciones que el año anterior en cuanto a las vacunas hexavalentes y a la vacuna neumocócica conjugada de 13 serotipos, al refuerzo con tétanos, difteria, tosferina y poliomielitis inactivada (Tdpa-VPI) a los seis años y con tétanos, difteria y tosferina (Tdpa) a los 12-14 años y a las embarazadas a partir de la semana 27 (desde la semana 20 si hay alto riesgo de parto pretérmino).

Lo mismo sucede con las vacunas del rotavirus, del meningococo B tetraantigénica (2 + 1), de la vacuna meningocócica tetravalente (MenACWY), de la triple vírica, de la varicela y de la vacuna del virus del papiloma humano (VPH), en ambos géneros.

Como novedades este año el CAV-AEP recomienda:

La vacunación antigripal de seis a 59 meses de edad siempre que sea factible y no perjudique al programa vacunal dirigido a las personas de mayor riesgo.

En consonancia con las recomendaciones oficiales nacionales, el CAV-AEP recomienda el uso sistemático a partir de los 5 años de las vacunas para la COVID-19 de ARNm.

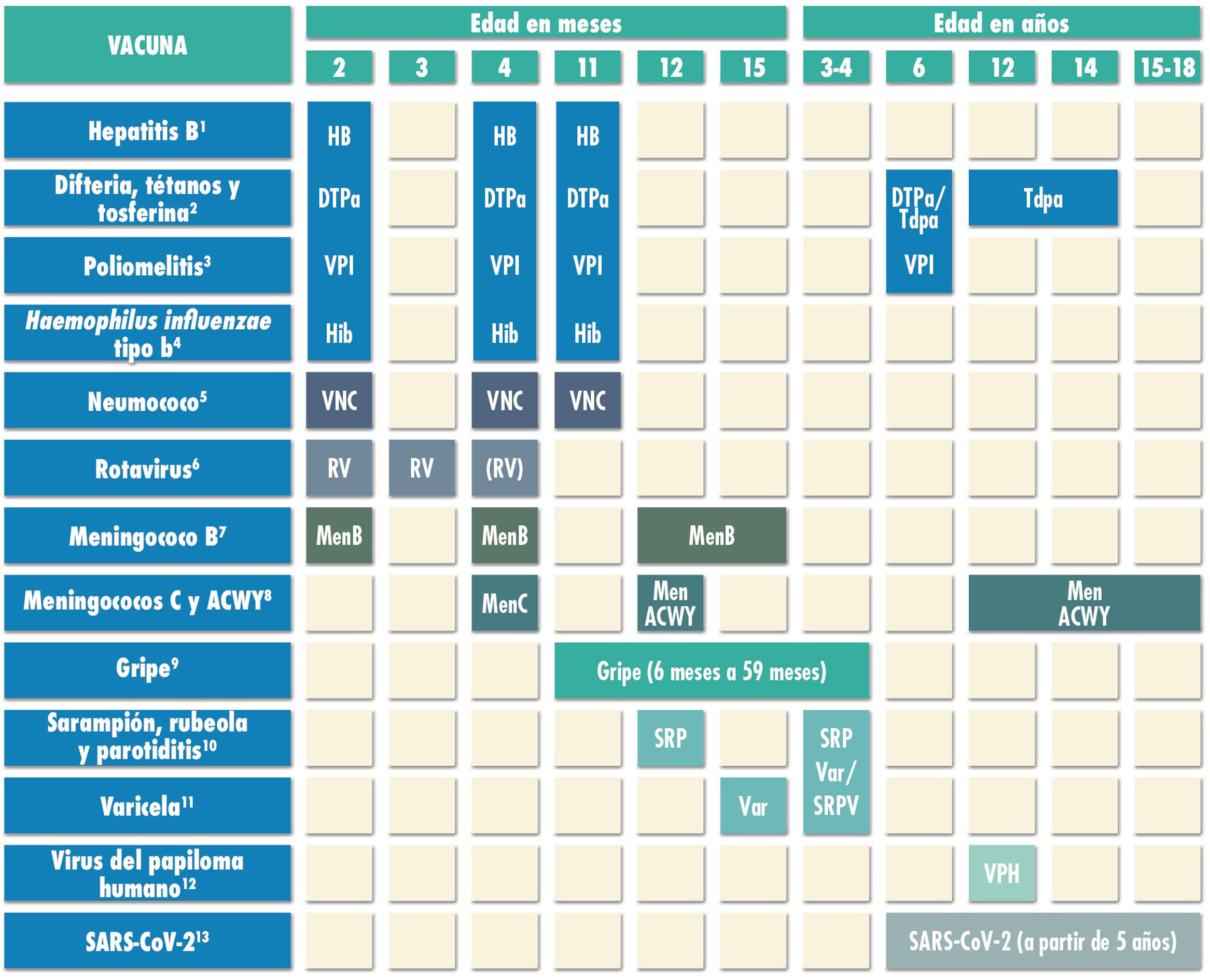

After a year that has proven the invaluable worth of vaccines in relation to health, the Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Paediatrics, AEP) (CAV-AEP) presents the annual update to the recommendations for vaccination in pregnant women, children and adolescents. These recommendations are developed through a consensus process following the review of all the relevant information currently available (Fig. 1). The grounds for these recommendations are explained in the website of the CAV-AEP (www.vacunasaep.org) and more detailed rationales can be found in the online Vaccine Manual of the AEP (https://vacunasaep.org/documentos/manual/manual-de-vacunas). Table 1 presents the vaccines that are commercially available in Spain.

Routine immunisation schedule of the Spanish Association of Pediatrics 2022.

(1) Hepatitis B vaccine (HB).- Three doses of hexavalent vaccine at ages 2, 4 and 11 months. Children of HBsAg-positive mothers or mothers of unknown serologic status will also be given one dose of monovalent HB vaccine at birth, in addition to 0.5mL of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) if maternal HBsAg-positive status is confirmed. Infants vaccinated at birth will adhere to the routine schedule for year 1 of life, and thus will receive 4 doses of HB vaccine. Unvaccinated children and adolescents should be given 3 doses of monovalent vaccine on a 0, 1 and 6-month schedule.

(2) Diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP/Tdap).- Five doses: primary vaccination with 2 doses, at 2 and 4 months, of DTaP-IPV-Hib-HB (hexavalent) vaccine; booster at 11 months (third dose) with DTaP (hexavalent) vaccine; at 6 years (fourth dose) with the standard load vaccine (DTaP-IPV), preferable to the low diphtheria and pertussis antigen load vaccine (Tdap-IPV), and at 12–14 years (fifth dose) with Tdap. In children previously vaccinated with the 3+1 schedule (at 2, 4, 6 and 18 months), it is possible to use the Tdap for the booster at age 6 years, as they do not need additional doses of IPV.

(3) Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).- Four doses: primary vaccination with 2 doses, at 2 and 4 months, and booster doses at 11 months (with hexavalent vaccine) and 6 years (with DTaP-IPV or Tdap-IPV). Children previously vaccinated with the 3+1 schedule (at 2, 4, 6 and 18 months), require no additional doses of IPV.

(4) Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine (Hib).- Three doses: primary vaccination at 2 and 4 months and booster dose at 11 months (with hexavalent vaccine).

(5) Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV).- Three doses: the first two at 2 and 4 months, with a booster dose starting at 11 months of age. The vaccine recommended in Spain by the CAV-AEP continues to be the PCV13.

(6) Rotavirus vaccine (RV).- Two or three doses of rotavirus vaccine: at 2 and 3–4 months with the monovalent vaccine or at 2, 3 and 4 months or 2, 3-4 and 5–6 months with the pentavalent vaccine. It is very important to start vaccination between 6 and 12 weeks of life in order to minimise risks, and to complete it before 24 weeks for the monovalent vaccine or 32 weeks for the pentavalent vaccine. Doses must be given at least 4 weeks apart. Both vaccines may be given at the same time as any other vaccine.

(7) Meningococcal B vaccine (MenB).- 4CMenB. Three doses: start at age 2 months, with a primary series of 2 doses 2 months apart and a booster starting at age 12 months and at least 6 months after the last dose in the primary series. It can be administered at the same time as other vaccines in the schedule, although this could increase the frequency of fever, so another option in patients up to age 12 months is to administer it 1 or 2 weeks apart from other injectable inactivated vaccines to minimise potential reactogenicity. The separation by 1-2 weeks is not necessary for the MenACWY, MMR, varicella and rotavirus vaccines. Vaccination is also recommended at any age in risk groups: anatomic or functional asplenia, complement deficiency, treatment with eculizumab or ravulizumab, haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, infection by HIV, prior episode of IMD caused by any serogroup, and contacts of an index case of IMD caused by serogroup B in the context of an outbreak.

(8) Meningococcal C conjugate vaccine (MenC) and meningococcal ACWY conjugate vaccine (MenACWY).- One dose of conjugate MenC-TT at age 4 months. The CAV-AEP recommends 1 dose of the MenACWY conjugate vaccine at age 12 months and 12–14 years, and a progressive catch-up vaccination schedule to be completed by age 18 years. In ACs where vaccination with MenACWY is not included in the routine schedule, if parents choose not to administer the MenACWY vaccine at 12 months, the MenC-TT vaccine funded by the regional government must be administered instead. Administration of the MenACWY vaccine is still particularly recommended in children and adolescents that are to live in countries where the vaccine is administered at this age (United States, Canada, Argentina, United Kingdom, Austria, Greece, Netherlands, Italy and Switzerland) and for children with risk factors for IMD: anatomic or functional asplenia, complement deficiency, treatment with eculizumab or ravulizumab, hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, HIV infection, prior episode of IMD caused by any serogroup, and contacts of an index case of IMD caused by serogroup A, C, W or Y in the context of an outbreak. Individuals traveling to Mecca for religious reasons and to the African meningitis belt during the dry season should also receive the MenACWY vaccine.

(9) Influenza vaccine.- Recommended in all children, with administration of the parenteral inactivated influenza vaccine in children aged 6 to 59 months and, if available, the intranasal live attenuated vaccine from age 2 years. Children who are being vaccinated for the first time and children under 9 years should receive 2 doses administered 4 weeks apart. Subsequently, only 1 dose is needed each season. The dose is 0.5mL in the case of the inactivated vaccine and 0.1mL in each nostril in the case of the attenuated vaccine. Information on the risk groups for influenza is available in the online Vaccine Manual of the AEP.

(10) Measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR).- Two doses of MMR vaccine. The first at age 12 months and the second at age 3–4 years. The quadrivalent MMRV vaccine may be administered for the second dose. Susceptible patients outside the specified ages will be vaccinated with 2 doses of MMR at least 1 month apart.

(11) Varicella vaccine (Var).- Two doses: the first at age 15 months (age 12 months is also acceptable) and the second at age 3–4 years. The quadrivalent vaccine (MMRV) may be used for the second dose. Susceptible patients outside the specified ages will be vaccinated with 2 doses of monovalent Var vaccine at least 1 month apart.

(12) Human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV).- Universal routine vaccination of all girls and boys, at age 12 years with a 2-dose series. The vaccines currently available are the HPV2 and HPV9. They are both authorised for use in male individuals. Vaccination with 2 doses of 2-valent or 9-valent vaccine at 0 and 6 months in children aged 9 to 14 years or a 3-dose series at 0, 1-2 and 6 months in those aged ≥15 years. The HPV vaccine may be administered at the same time as the MenC, MenACWY, hepatitis A and B and Tdap vaccines. There are no data on the coadministration with the varicella vaccine, although it should not cause any problems.

(13) SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.- Currently, two vaccines are authorized in our country from the age of 12, Comirnaty-30 microgr (Pfizer) and Spikevax-100 microgr (Moderna) and another between 5 and 11 years with another presentation with a lower amount of antigen (Comirnaty-10 microgr) . Two doses will be applied, separated by three weeks in the first and third and by four weeks in the second. The Public Health Commission of Spain has decided that the separation between the 2 doses of Comirnaty 10 mcgr is 8 weeks, but if it is administered after 21 days it would be valid. They can be administered with other vaccines on the same day or with the desired separation.

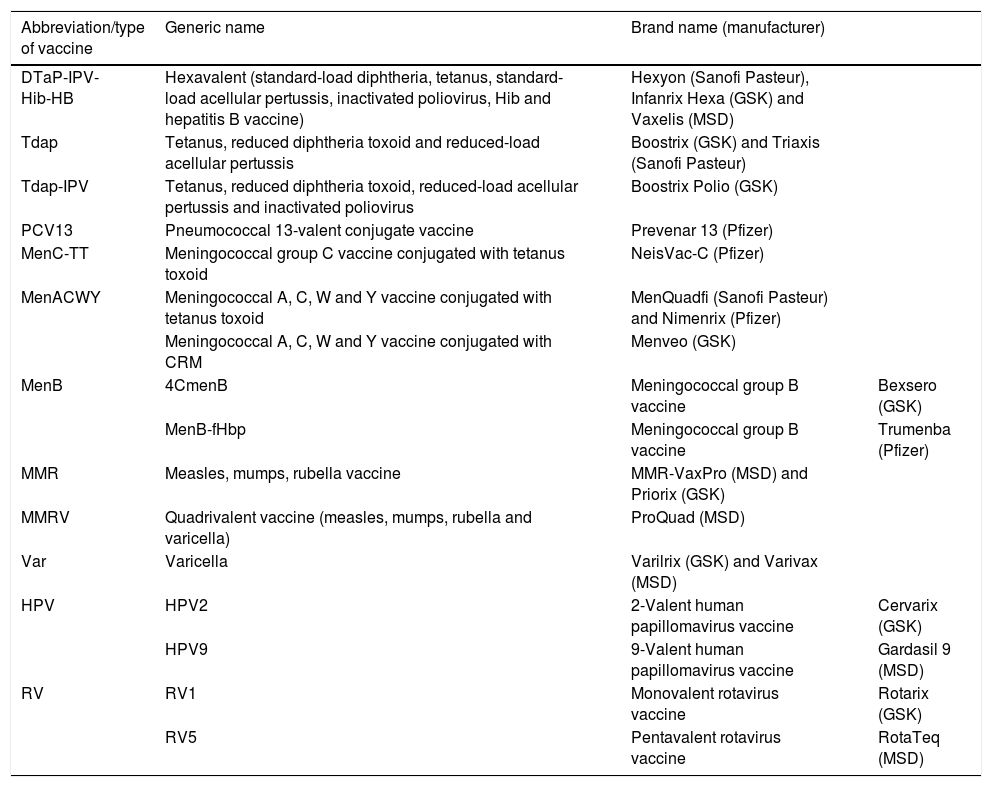

Abbreviations, generic names and brand names of vaccines recommended for routine immunisation by the CAV-AEP currently available in Spain.

| Abbreviation/type of vaccine | Generic name | Brand name (manufacturer) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTaP-IPV-Hib-HB | Hexavalent (standard-load diphtheria, tetanus, standard-load acellular pertussis, inactivated poliovirus, Hib and hepatitis B vaccine) | Hexyon (Sanofi Pasteur), Infanrix Hexa (GSK) and Vaxelis (MSD) | |

| Tdap | Tetanus, reduced diphtheria toxoid and reduced-load acellular pertussis | Boostrix (GSK) and Triaxis (Sanofi Pasteur) | |

| Tdap-IPV | Tetanus, reduced diphtheria toxoid, reduced-load acellular pertussis and inactivated poliovirus | Boostrix Polio (GSK) | |

| PCV13 | Pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine | Prevenar 13 (Pfizer) | |

| MenC-TT | Meningococcal group C vaccine conjugated with tetanus toxoid | NeisVac-C (Pfizer) | |

| MenACWY | Meningococcal A, C, W and Y vaccine conjugated with tetanus toxoid | MenQuadfi (Sanofi Pasteur) and Nimenrix (Pfizer) | |

| Meningococcal A, C, W and Y vaccine conjugated with CRM | Menveo (GSK) | ||

| MenB | 4CmenB | Meningococcal group B vaccine | Bexsero (GSK) |

| MenB-fHbp | Meningococcal group B vaccine | Trumenba (Pfizer) | |

| MMR | Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine | MMR-VaxPro (MSD) and Priorix (GSK) | |

| MMRV | Quadrivalent vaccine (measles, mumps, rubella and varicella) | ProQuad (MSD) | |

| Var | Varicella | Varilrix (GSK) and Varivax (MSD) | |

| HPV | HPV2 | 2-Valent human papillomavirus vaccine | Cervarix (GSK) |

| HPV9 | 9-Valent human papillomavirus vaccine | Gardasil 9 (MSD) | |

| RV | RV1 | Monovalent rotavirus vaccine | Rotarix (GSK) |

| RV5 | Pentavalent rotavirus vaccine | RotaTeq (MSD) |

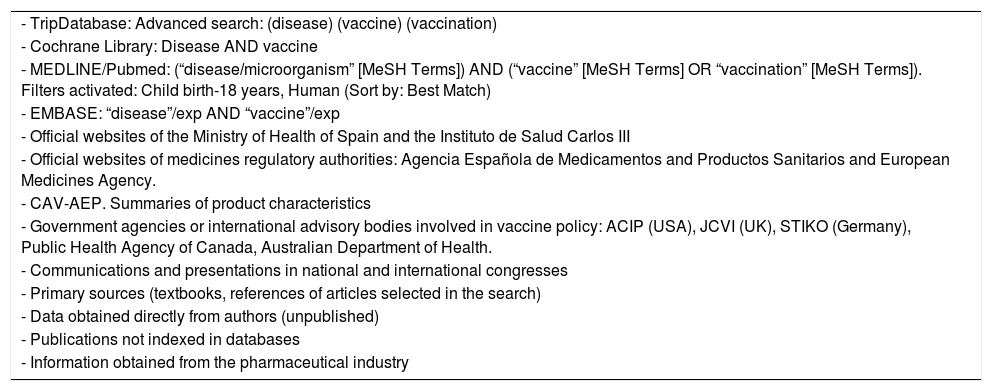

The purpose of the documents published by the CAV-AEP is to provide practical information on the vaccines indicated for use in children and adolescents based on the epidemiological context in Spain and to encourage a shift away from the pharmacoeconomic criteria historically applied to establish vaccination policies in the paediatric population. Table 2 shows the sources of information and bibliographic search strategies for the document.

Bibliographic sources and literature search strategies used in the development of this document.

| - TripDatabase: Advanced search: (disease) (vaccine) (vaccination) |

| - Cochrane Library: Disease AND vaccine |

| - MEDLINE/Pubmed: (“disease/microorganism” [MeSH Terms]) AND (“vaccine” [MeSH Terms] OR “vaccination” [MeSH Terms]). Filters activated: Child birth-18 years, Human (Sort by: Best Match) |

| - EMBASE: “disease”/exp AND “vaccine”/exp |

| - Official websites of the Ministry of Health of Spain and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III |

| - Official websites of medicines regulatory authorities: Agencia Española de Medicamentos and Productos Sanitarios and European Medicines Agency. |

| - CAV-AEP. Summaries of product characteristics |

| - Government agencies or international advisory bodies involved in vaccine policy: ACIP (USA), JCVI (UK), STIKO (Germany), Public Health Agency of Canada, Australian Department of Health. |

| - Communications and presentations in national and international congresses |

| - Primary sources (textbooks, references of articles selected in the search) |

| - Data obtained directly from authors (unpublished) |

| - Publications not indexed in databases |

| - Information obtained from the pharmaceutical industry |

A unified nationwide immunization schedule would offer equal benefits to children throughout Spain, so the CAV-AEP is taking a stance before society and the public health authorities to achieve this objective in the near future. The committee emphasises the pressing need to reinforce primary care services as a crucial element for achievement of optimal vaccination coverage (currently threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic). Inequalities in the access to vaccines could be remedied through specific interventions to target socially disadvantaged populations, the implementation of copay programmes to help fund administration of vaccines that are not included in official immunization or the use of global access channels providing truthful information about vaccines.

With the advent of the pandemic and the development of vaccines against COVID-19, the members of the CAV-AEP have played a key role in the messages issued to the population from the Ministry of Health and other scientific societies, which constitutes progress in the involvement of paediatricians in the development of national vaccination strategy, in line with the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) and policymaking in neighbouring countries.

This document presents the current recommendations for vaccination highlighting the introduced changes.

VACCINATION AGAINST HEPATITIS B2022 recommendation:3 doses of hexavalent vaccine at 2, 4 and 11 months of age.

Hepatitis B (HB) is a disease found worldwide. Spain is a low-endemic country, with a prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) detection of 0.2% to 0.5%, of antibodies against HBsAg of 4% to 6% and a low incidence of neonatal and paediatric infection.1

The complete vaccination series generates an antibody response that achieves protective levels in more than 95% of infants, children and young adults (https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b).

Vaccination in infants requires 3 doses of hexavalent vaccine (at ages 2, 4 and 11 months). In the case of potential risk of vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, a dose of monovalent HB vaccine should be administered to the infant at birth, in addition to 0.5mL of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) within 12hours of birth. Vaccination will be completed following the regular schedule, with administration of a total of 4 doses.

We recommend a minimum of 4 weeks between the administration of the first and second doses and of 8 weeks between the administration of the second and third doses. Delaying administration of the final dose to age 11 to 12 months increases vaccine immunogenicity.2

Unvaccinated children and adolescents of any age will be given 3 doses of monovalent vaccine (or together with the hepatitis A vaccine, if indicated) on a 0-, 1- and 6-month schedule.

VACCINATION AGAINST DIPHTHERIA, TETANUS, PERTUSSIS, POLIOMYELITIS AND HAEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE TYPE B2022 recommendation:2+1 schedule with the hexavalent vaccine (DTaP-IPV-Hib-HB) at 2, 4 and 11 months, at 6 years with the tetanus, standard diphtheria toxoid, standard-load acellular pertussis and inactivated poliovirus vaccine (DTaP-IPV), preferably, or with the tetanus, reduced diphtheria toxoid, reduced-load acellular pertussis and inactivated poliovirus vaccine (Tdap-IPV), and Tdap at age 12 to 14 years. The first dose can be administered earlier starting at 6 weeks post birth. We recommend vaccination with Tdap of all pregnant women in each pregnancy, preferably between 27 and 32 weeks of gestation, as early as possible within this window. In case of high risk of preterm birth, vaccination could be given starting at 20 weeks.

Vaccination on a 2+1 schedule with hexavalent vaccines is safe and effective. This schedule was introduced in Spain in 2016 and requires a fourth dose of IPV at 6 years to complete vaccination against poliomyelitis, for which we recommend administration of the DTaP-IPV vaccine if available, with administration of the Tdap-IPV if it is not available or if the child is aged more than 7 years. The fifth dose is given with the Tdap vaccine in adolescence, thus completing the schedule recommended through age 60 to 65 years and boosting the protection against pertussis in adolescents, who can acquire and transmit the disease given that neither previous vaccination nor having had the infection confer lasting immunity.

Pertussis affects individuals of all ages, but the risk of severe disease or death is greater in young infants. Vaccination during pregnancy is effective not only in preventing the disease, but also in reducing its severity in infants.3 In a systematic review of global scope, Kandeil found that this strategy was 69% to 93% effective in preventing pertussis and 90.5% effective in preventing pertussis-related hospital admission in infants under 3 months.4

The optimal timing of vaccination in pregnancy and the potential interference of maternal antibodies with infant responses to primary vaccination (blunting) continue to be subjects of debate.5 Vaccine effectiveness does not seem to vary based on whether vaccination takes place in the second or third trimester, and although blunting can occur, differences have not been found between the infants born to vaccinated versus unvaccinated women after the pertussis vaccine booster at 11 months. Although the benefits of maternal vaccination extend beyond 3 months, delaying primary vaccination past this point to prevent blunting does not seem justified given that this affects immunization against the other pathogens included in the hexavalent vaccine.

VACCINATION AGAINST PNEUMOCOCCAL DISEASE2022 recommendation:Vaccination against pneumococcal disease is recommended for all children younger than 5 years and children of any age that belong to any risk group with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). A 2+1 series (at 2, 4 and 11 months) is recommended for routine vaccination of healthy infants.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) offer protection against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) as well as non-invasive disease (pneumonia and acute otitis media).6 Their use is also associated with a reduction in antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use.7 In Spain, routine childhood vaccination has achieved a significant reduction in the burden of IPD in both children and adults.8

After the introduction of PCVs, there has been evidence of an increase in the incidence of non-vaccine serotypes.9 This has motivated the development of vaccines covering a greater number of serotypes.10 The PCV13 is the vaccine that offers the best coverage for the serotypes currently circulating in Spain.11,12

VACCINATION AGAINST ROTAVIRUS2022 recommendation:Vaccination against rotavirus (RV) should be included in the routine immunisation schedule for all infants.

The WHO (https://www.who.int/news/item/20-11-2015-statement-from-the-global-advisory-committee-on-vaccine-safety), the European Academy of Paediatrics and the European Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases support this recommendation.13

More than 110 countries include the RV vaccine in their routine immunisation schedules. The public health benefits of this vaccine are incontrovertible and far exceed those of hygiene measures.

Preterm infants, in whom vaccination is publicly funded on account of their risk-group status, should be vaccinated without delay, even if they are hospitalised, between 6 and 12 weeks post birth.14

A recent meta-analysis that assessed the effect of the vaccine in more than 100 000 children corroborated the effectiveness and safety data published to date and concluded that its benefits outweigh its costs.15

VACCINATION AGAINST MENINGOCOCCAL DISEASE2022 recommendation:Routine vaccination against meningococcus B is recommended in all infants starting at 2 months of age with a 2+1 schedule. In all other age groups, including adolescents, the decision whether to vaccinate will be made on a case-by-case basis. We recommend using the meningococcal group C vaccine conjugated with tetanus toxoid (MenC-TT) at 4 months with administration of the quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (MenACWY) at 12 months instead of MenC-TT. It is essential that, should a child not be given the latter vaccine, the dose of MenC-TT is administered without fail. We continue to recommend administration of the MenACWY vaccine to adolescents at age 12 years, and catch-up vaccination is recommended up to age 18 years. For all other paediatric age groups, the decision to vaccinate will be made on a case-by-case basis.

In Spain, 2 vaccines are currently available for prevention of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) due to group B meningococcus (MenB): the 4CMenB vaccine (from age 2 months) and the MenB-fHbp vaccine (from age 10 years).

Since IMD caused by group B meningococcus is very rare, conventional cost-benefit analyses of this vaccine (in terms of quality-adjusted life years, or QALY) are unfavourable. In addition, the measures taken to confront the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic have contributed to a marked decrease in the number of cases of disease caused by any serogroup. Notwithstanding, the CAV-AEP advocates for routine vaccination of infants, as group B meningococcus is the serogroup isolated most frequently in infants aged less than 12 months in Spain, the group most affected by this devastating disease. Since 2019, the Canary Islands and Castilla y Leon have included it in their immunization schedules, and Andalusia introduced it in 2021.

There is ample evidence of the effectiveness of the 4CMenB. In the United Kingdom (UK), following its introduction in the routine immunization schedule in 2015, there has been a 75% decrease in incidence relative to the expected cases, corresponding to the prevention of an estimated 277 cases (95% confidence interval, 236–323) in the first 3 years of the programme. The complete 2+1 series had an effectiveness of 71.2% in preventing disease caused by vaccine serotypes.16 These data led to the revision of the summary of product characteristics in 2020 to authorise this vaccination schedule starting at age 2 months.

The vaccine also proved effective in Italy after its inclusion in the infant vaccination programme in the regions of Tuscany (effectiveness, 93.6%; 95% CI, 55.4%–99.1%) and Veneto (91.0%; 95% CI, 59.9%–97.9%), with the impact increasing with initiation of the vaccine series at age 2 months.17

In Portugal, the vaccine was introduced in the schedule after a study estimated an effectiveness of 79% (95% CI, 45%–92%).18 Recently, the National Authority for Health in France recommended vaccination of infants against meningococcal disease s.

Therefore, we continue to recommend the inclusion of the 4CMenB in the routine immunization schedule with a 2+1 schedule starting at age 2 months. Administration of the vaccine in other age groups, including adolescents, would be for the purpose of individual protection, as vaccination does not reduce nasopharyngeal carriage of MenB or contribute to heard immunity.19

The marked increase in the incidence of IMD caused by groups W and Y worldwide 20 has motivated the replacement in some countries of the MenC dose by a dose of MenACWY in adolescence or even in the second year of life, seeking to protect young children directly on account of their greater vulnerability. In Spain, an increase in the incidence of IMD by groups W and Y was detected in the 2014–2015 period, a trend that was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The most recent data of the Centro Nacional de Epidemiología (https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Boletines/Paginas/BoletinSemanalEnRed.aspx) show a sustained decrease in IMD caused by any serogroup. This decrease has been observed in many other countries, such as the UK, mainly on account of the measures taken to contain the pandemic.21 However, given the unpredictable epidemiology of this disease, the CAV-AEP insists on the need to maintain a high vaccination coverage.

Catch-up vaccination between 13 and 18 years was suspended in most ACs due to the pandemic, making it difficult for vaccination to have a sufficient epidemiological impact to protect infants indirectly. The CAV-AEP continues to support the replacement of the dose of MenC by a dose of MenACWY in adolescence and at age 12 months to provide direct protection to infants. In case the MenACWY vaccine is not given at 12 months, it is important to ensure administration of a dose of MenC to prevent a decrease in vaccination coverage.

In other paediatric age groups, the decision whether to vaccinate will be made on a case-by-case basis.

VACCINATION AGAINST INFLUENZA2022 recommendation:annual vaccination against influenza should be included in the routine immunization schedule for all children aged 6 to 59 months.

Seasonal influenza has a high incidence in previously healthy children, and every year it causes significant morbidity in the paediatric population. In addition, young children are significant vectors of transmission to adults and the elderly.

Although it is commonly believed that influenza mainly affects children with underlying conditions, multiple studies have evinced the significant impact of this disease in healthy children.22

The influenza vaccine is the most effective measure of prevention. Since 2012, the WHO and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) recommend considering children aged 6 to 59 months a priority group for vaccination against influenza.23,24

We have effective and safe vaccines for the paediatric population. Childhood immunization is one of the most effective measures to reduce the global burden of disease in both children and adults, and especially in elderly individuals, who mount poorer responses to the vaccine. Several studies have found a reduction in morbidity and mortality in the elderly population associated with vaccination against influenza in the paediatric population.

VACCINATION AGAINST MEASLES, MUMPS AND RUBELLA (MMR)2022 recommendation:The first dose will be given at age 12 months with the MMR, and the second at age 3-4 years with the quadrivalent vaccine (MMR+varicella, MMRV).

Spain is considered free of indigenous measles. Maintaining a vaccination coverage above 95% for the 2 doses is essential.

In 2020 (https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Boletines/Paginas/BoletinSemanalEnRed.aspx), there were 72 reported cases of measles, 3 of rubella (excluding congenital rubella) and 6220 of mumps.

The second seroprevalence survey in Spain25 found that the proportion of the population with antibody titres protective against measles decreased 10 to 15 years from vaccination, while immunity against rubella was found in more than 95% of the population at all ages and the protection against mumps was high between ages 2 and 14 years, after which it waned.

We recommend administration of the first dose at age 12 months with the MMR and of the second dose at 3–4 years with the MMRV. Administration of the second dose is essential to remedy potential primary vaccine failure with the first dose and ensure adequate herd immunity.

When children under 12 years need to be vaccinated for epidemiological reasons, the MMR can be administered to infants aged 6 to 11 months, but this does not count towards the 2 doses required for complete vaccination.

We continue recommending separate administration of the MMR and varicella vaccines for the first dose of the series in children aged less than 2 years due to the risk of febrile seizures.26

VACCINATION AGAINST VARICELLA2022 recommendation:we recommend routine vaccination with 2 doses, at 15 months and 3-4 years (he MMRV vaccine may be used for the second dose). For unvaccinated children and adolescents that have not had the disease, we recommend catch-up vaccination with a 2-dose series.

Two monovalent and two quadrivalent MMRV vaccines are currently available, all of them with attenuated virus, and are highly effective (92%–97%).27

The inclusion of the varicella vaccine in childhood immunization schedules is safe and cost-effective. To prevent varicella in vaccinated individuals and circulation of the virus, a 2-dose series is necessary.28 Since 2016, all ACs offer routine vaccination against varicella (at 15 months and 3–4 years). The MMRV is given for the second dose in 9 ACs.

According to several studies, the incidence of herpes zoster in children vaccinated against varicella is lower compared to the incidence in unvaccinated children with a history of primary varicella-zoster virus infection.29

VACCINATION AGAINST HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS (HPV)2022 recommendation:Routine vaccination against HPV is recommended, preferably at age 12 years, with 2 doses of vaccine, independently of sex.

The recommended age for vaccination is 12 years, prior to sexual debut, with the aim of maximizing its possible benefits and optimising vaccination coverage. We also recommend catch-up vaccination and vaccination of individuals in risk groups

The causal role of human papillomavirus (HPV) has been demonstrated not only in cervical cancer, but also in other cancers affecting individuals of both sexes, such as anal cancer or head and neck cancers.30 The effectiveness of the available vaccines translates to a reduction of nearly 85% in the incidence of high-grade lesions,31 anogenital cancer in males32 and genital warts in both sexes. There is also evidence suggesting an impact on oropharyngeal cancer.33 On the other hand, data are already available on the effectiveness of vaccination against cervical cancer.34

The HPV vaccines are extremely safe and offer a very favourable risk-benefit ratio. In Spain, the vaccines authorised for use in both sexes cover 2 (HPV2) or 9 (HPV9) genotypes. Although both offer protection, the HPV9 vaccine offers the broadest direct coverage against cervical cancer (90%) and potential prevention of 85% to 95% of HPV-related vulvar, vaginal and anal cancers; in addition to genital warts.35

The CAV-AEP recommends routine vaccination against HPV in children of both sexes with the HPV vaccine selected by the regional government (HPV2 in 4 ACs and HPV9 in the rest of Spain).

Vaccination against SARS-CoV-22022 recommendation:vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is recommended from age 5 years.

Vaccination of all children against SARS-CoV-2 is recommended, provided there is an approved vaccine for their age. This recommendation is based on: 1) contemplating the child's right to individual protection against this disease; 2) achieve and maintain safe educational spaces that allow the normalization of schooling and interpersonal relationships of children, with the consequent psycho-emotional well-being; 3) achieve group immunity; 4) reduce the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 and prevent the appearance of new variants and 5) it would not be fair to deprive the child population of the benefit of vaccination.

The global burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children is unknown, since in up to 50% of them the infection can be asymptomatic. At present, in Spain, the incidence of COVID-19 is higher in children under the age of 11 than at any other age.36

Although the disease is mild in most children, is not without risks. In Spain, the hospitalization rate in children is 4-6 per 1,000 infected, the admission rate to the PICU is 3-4 / 10,000, and the case fatality rate is 2-4 / 100,00037. However, since the beginning of the pandemic, there have been at least 6,000 hospitalizations, 300 admissions to the PICU, and 37 deaths from COVID-19, half of them in children under 10 years of age.38

Children seem become infected and transmit the disease to a lesser degree than adults39,40. However, it is possible that these differences are due to variations in social behaviors, according to age, since in the home environment the risk of contagion and transmission of the disease is the same for all ages.41

Currently, there are three vaccines mRNAs authorized for children and adolescents: two for children over 12 years of age, the BNT162b2 vaccine (Comirnaty-Pfizer) and the amRNA-1273 vaccine (Spikevax-Moderna), and a third Comirnaty preparation, with a lower mRNA load , for children 5-11 years old. The efficacy against symptomatic infection in the first two has been 100% and in the third 90.7%. All three are very safe vaccines, with side effects limited, in most cases, to local reactions at the site of the infection. injection, headache, fatigue and mild fever.42–44

After clinical use of Comirnaty and Spikevax, some myocarditis events associated with this vaccine have been detected, which resolves in 2-3 days in the vast majority of cases45. Even considering this complication, the benefit / risk balance is clearly favorable to these vaccines, since it is more frequent after infection than after vaccination (https://vacunasaep.org/profesionales/noticias/comirnaty-y-myocarditis). It is very likely that the balance is even more favorable in children aged 5-11 years, since the incidence of myocarditis associated with the vaccine decreases below 15 years.

FUNDINGThe development of these recommendations (analysis of the published data, debate, consensus and publication) has not been supported by any funding source outside of the logistic support provided by the AEP.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTPotential conflicts of interest of the authors (last 5 years):

FJAG has collaborated in educational activities funded by Alter, Astra, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur advisory boards.

MJCO has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur, as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur.

JAA has collaborated in educational activities funded by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur and Seqirus, as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur and as a consultant in AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur and Seqirus advisory boards.

MGS has collaborated in educational activities funded by Astra, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur, as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MSD and Sanofi Pasteur and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis advisory boards.

EGL has received funding to attend domestic educational activities and has participated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur, as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and MSD and as a consultant in a GlaxoSmithKline advisory board.

AIA has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur, has received funding from Pfizer to attend domestic educational activities, and has participated in educational activities funded by GSK, MSD and Pfizer.

AMM has received funding from Pfizer to attend educational activities in Spain and abroad, but stopped accepting any type of direct sponsoring from any pharmaceutical laboratories for any type of activity (as an educator or as an attendant) since becoming a member of the CAV-AEP. He also has collaborated as a researcher without remuneration in a study sponsored by MSD in 2019-20.

MLNG has collaborated in educational activities funded by Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and ViiV, as a consultant for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis and ViiV advisory boards and as a researcher in clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi Pasteur.

VPS has received funding from MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur to attend educational activities in Spain and abroad, has collaborated in educational activities funded by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur advisory boards.

IRC has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur, as a researcher in vaccine clinical trials for Ablynx, Abbot, Cubist, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Medimmune, Merck, MSD, Novavax, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Regeneron, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus and Wyeth and as a consultant in MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur advisory boards.

JRC has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur and as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

PSM has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline and MSD, as a researcher in clinical trials for Sanofi Pasteur and as a consultant in a GlaxoSmithKline advisory board. He has also received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, MSD and Pfizer to attend educational activities in Spain and abroad, and received grants sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

We thank Javier Arístegui, José María Corretger, Nuria García Sánchez, Ángel Hernández Merino, Manuel Merino Moína and Luis Ortigosa for their in-house advice on the development and writing of these guidelines.

Francisco José Álvarez García (FJAG), María José Cilleruelo Ortega (MJCO), Javier Álvarez Aldeán (JAA), María Garcés-Sánchez (MGS), Elisa Garrote Llanos (EGL), Antonio Iofrío de Arce (AIA), Abián Montesdeoca Melián (AMM), Marisa Navarro Gómez (MLNG), Valentín Pineda Solas (VPS), Irene Rivero Calle (IRC), Jesús Ruiz-Contreras (JRC), Pepe Serrano Marchuet (PSM).

Please cite this article as: Álvarez García FJ, Cilleruelo Ortega MJ, Álvarez Aldeán J, Garcés-Sánchez M, Garrote Llanos E, Iofrío de Arce A, et al. Immunization schedule of the Pediatric Spanish Association: 2022 recommendations. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:59.

The members of the Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría are listed in Appendix 1.