It is estimated that 90% of preterm newborns (PTIs) with birth weights of less than 1000 g receive at least one packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusion and a smaller percentage platelets and/or fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusions. However, there is an obvious lack of scientific evidence in relation to the indications and benefits of transfusion practices in this subset of patients.

The recent Effects of Transfusion Thresholds on Neurocognitive Outcomes of Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants (ETTNO)1 and Transfusion of Prematures (TOP)2 trials have demonstrated that the use of restrictive strategies in the PRBC transfusion is not inferior in terms of survival and neurocognitive outcomes to liberal strategies based on higher haemoglobin thresholds. With regard to platelets, the Platelets for Neonatal Thrombocytopenia (PlaNeT-2)/Management of Thrombocytopenia in Special Subgroup (MATISSE)3 trial compared a liberal (50 000/dL) threshold for the indication of transfusion with a more restrictive one (25 000/dL), and found higher rates of death and major bleeding in the high-threshold group. These studies evinced the lack of knowledge of the pathophysiological processes underlying haematological disorders in PTIs.

In light of this situation, a European survey was carried out on the initiative of the Neonatal Transfusion Network, with participation of 343 centres in 18 countries.4 In this framework, we carried out a substudy between December 2020 and April 2021 in level III neonatal units in Spain to assess the customary clinical practice in the use of blood products in PTI born at or before 32 weeks of gestation and analyse how it compares to the results of the most recent clinical trials and with the current overall situation in the Europe.

To do so, we used an online that was sent to the main neonatal intensive care units across Spain. We contacted a total of 58 units, of which 41 (70%) responded. Table 1 presents the results regarding transfusion practices. In general, there was little variability between the surveyed facilities in the haemoglobin threshold used to determine the indication of transfusion support. The median PRBC volume delivered in Spanish hospitals was 15 mL/kg (interquartile range [IQR]: 15–20 mL/kg), the volume of platelets 15 mL/kg (IQR, 10–15 mL/kg) and the volume of FFP 15 mL/kg (IQR, 12.5–15 mL/kg). When it came to the indications for the administration of FFP, there was consensus in regard to its use for management of coagulopathy associated with bleeding. However, there were significant discrepancies between the surveyed centres in regard to other indications, such as coagulopathy without bleeding and bleeding in the absence of coagulopathy.

Data of the national survey of transfusion protocols.

| Thresholds for transfusion of packed red blood cells in different clinical scenarios, median (IQR), expressed in g/dL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 week | 1–2 weeks | >2 weeks | |

| No O2 | 10 (10) | 9.5 (8–10) | 8 (7–8.5) |

| Low-flow O2 | 10 (10–11) | 10 (9–10) | 8.5 (8–9) |

| O2 with FiO2 < 30 | 12 (11–12) | 10 (10–12) | 9.5 (8–10) |

| O2 with FiO2 > 30 | 12 (12–12) | 11 (10–12) | 10 (9.5–10) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 12 (12) | 12 (10–12) | 10 (10–11) |

| Volume: 15 mL/kg (IQR, 15–20 mL/kg) | |||

| Transfusion time: 3 h (IQR, 2–4 h) | |||

| Thresholds for platelet transfusion in different clinical scenarios (median, (IQR) expressed in platelets/dL) | ||

|---|---|---|

| <28 weeks | 28–32 weeks | |

| No bleeding | 30 000 (20–50 × 103) | 25 000 (25–30 × 103) |

| Bleeding | 50 000 (50–100 × 103) | 50 000 (50–90 × 103) |

| Volume: 15 mL/kg (IQR, 10–15 mL/kg) | ||

| Transfusion time: 2 h (IQR, 2–3 h) | ||

| Indications for transfusion of fresh frozen plasma | |

|---|---|

| Coagulopathy with bleeding | 100% |

| Coagulopathy without bleeding | 43.9% |

| Bleeding without coagulopathy | 39% |

| Hypotension | 4.9% |

| Volume: 15 mL/kg (IQR, 12.5–15 mL/kg) | |

| Duration of transfusion: 3 h (IQR, 3–4 h) | |

The table presents the thresholds for packed red blood cells and platelet transfusion, expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), for different clinical scenarios and gestational ages. It also includes information on the median volume administered and the median duration of transfusion, as well as the indications for fresh frozen plasma.

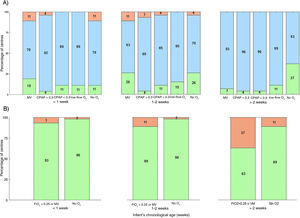

Fig. 1 compares the applied haemoglobin thresholds to the thresholds established in the trials mentioned above.1,2 We found that, on average, 13.3% of Spanish units applied restrictive thresholds, 83% intermediate thresholds and 3.5% liberal thresholds. In the European survey, up to 30% of the units applied restrictive thresholds, more than double the percentage in Spain, and 68% applied intermediate thresholds. Recently, the Standards Committee of the Sociedad Española de Neonatología (SENeo) published recommendations to standardise the transfusion of blood products in neonatal care nationwide.5Fig. 1 presents the comparison of real-world practice with the thresholds recommended by the SENeo, evincing good concordance with recommendations in the first two weeks of life, but the use of much more liberal thresholds after the second week.

Current situation of PRBC transfusions in relation to the thresholds used in the ETTNO and TOP clinical trials (A) and the recommendations of the SENeo (B). Data presented in stacked bar charts showing the percentage of neonatal units that use different PRBC transfusion thresholds in different clinical scenarios and in infants with different gestational ages (weeks). In the charts at the top, the reference thresholds are those reported for the ETTNO and TOP trials: (A) at or below the restrictive (green), between the restrictive and liberal thresholds (blue) and above the liberal threshold (red). At the bottom, the thresholds correspond to the recommendations of the SENeo (B): at or below the threshold (green) and above the threshold (red). The colours of the figure can only be seen in the online version.

As regards the thresholds applied for the transfusion of platelets, in PTIs delivered before 28 weeks, 37% of the centres applied a restrictive threshold, a percentage that rose to 57% for PTIs delivered between 28 and 32 weeks. These results were similar to those of the European survey and in agreement with the recommendations derived from the findings of the PlaNeT2/MATISSE trial.

Based on our findings, we ought to highlight that Spanish neonatal units have more restrictive policies when it comes to platelet transfusion compared to the thresholds applied for the treatment of anaemia, which suggests an uneven application of scientific evidence to clinical practice. The most liberal transfusion policies beyond the first two weeks of life suggest a tendency to maintain the same transfusion thresholds established in the first weeks. In addition, there was substantial variability in the indications for FFP.

In conclusion, our study evinced that transfusion policies diverged from recommendations in varying degrees. The fact that a large majority of hospitals used local protocols may be one of the factors contributing to the observed heterogeneity and hindering the application of the most recent evidence. These findings underscore the need to continue to promote research on transfusion, which will contribute to increase the quality and safety of the care provided to PTIs.