The urethra does not usually attract the interest of paediatricians during the initial management of a polytraumatised patient; so it is common that in patients with multiple trauma, especially those with pelvic fractures or perineal injuries, urologic lesions (present in 7.4–13.5% of paediatric pelvic trauma) are discovered when catheterisation cannot be performed or is extremely painful.1,2 Injuries of the anterior urethra (penile and bulbar) are caused by falls on the perineum (“straddle” falls); while injuries of the posterior urethra (membranous and prostatic) are associated with pelvic fractures, especially unstable ones (Malgaigne).1–3 The diagnosis and classification of these injuries are based on retrograde urethrography. The initial procedure in childhood urethral injuries is suprapubic derivation (a tube cystostomy),1–4 and it is convenient if feasible and Given enough experience to start management with endoscopic realignment within the first days.1–4 Early open urethral realignment is not recommended (there is risk of harming vascular and neural structures.)1–4 The long-term sequelae of urethral injury are stricture, urethrocutaneous fistulae, urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction (ED). Strictures require different interventions a few months after the trauma: open surgery (urethroplasty: tension-free end-to-end anastomosis or buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty using the transperineal—most frequently—or the transpubic approach), or endoscopic surgery (urethrotomy: resection of short strictures).1–4 Strictures recur frequently after a first intervention (it may occur years after the procedure).

In this paper we present a series of 3 cases that illustrate the complexity of the management of posterior urethral trauma and the importance of its sequelae.

Case 1. Male aged 13 years with pelvic trauma (motorcycle accident), pelvic fracture and rupture of the posterior urethra. The initial management was a suprapubic catheter. He developed a posterior urethral stricture and urethrocutaneous fistulae. End-to-end urethroplasties were performed at 6 and 9 months post-surgery, with full recurrence of the stricture after each. A surgery for continent urinary diversion (Mitrofanoff procedure) with surgical closure of the bladder neck was performed at 14 months post-surgery. Twelve years after the trauma, he was fitted with an intermittent catheterization but suffered from chronic orchidoepididymitis and severe ED.

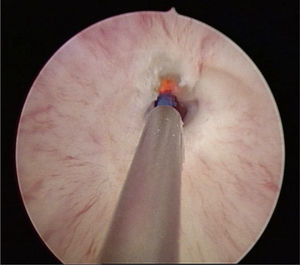

Case 2. Male aged 9 years with pelvic and urethral trauma (bicycle fall). The initial management consisted of a permanent suprapubic catheter. End-to-end urethroplasty was performed at 2 months post-surgery, with the stricture recurring. A second urethroplasty (buccal mucosa graft) was performed one year later and was unsuccessful (the stricture recurred), with recurrent orchitis. Two and a half years after the accident, it was decided to perform an endoscopic urethrotomy (Fig. 1), and the stricture recurred again. Two end-to-end urethroplasties followed (bulbomembranous urethra) at 4 and 5 years post-surgery. Six years after the surgery, and one year after the latest urethroplasty, the patient was asymptomatic and the urethral stricture had not recurred.

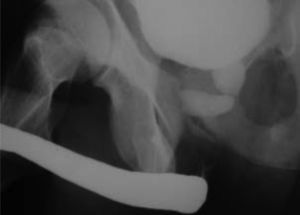

Case 3. Male aged 12 years with pelvic trauma (crushing) and rupture of the prostatic urethra (Fig. 2). Primary endoscopic realignment was performed. Endoscopic internal urethrotomies were performed at 5, 6, 9 and 14 months post-surgery. Transurethral lithotripsies were performed at 5 and 18 months after the patient developed vesicular lithiasis. An end-to-end urethroplasty was performed at 2 years post-surgery, and since the stricture recurred, a transpubic urethroplasty was performed at 3 years post-surgery. At 14 years post-surgery, the patient suffered from urinary incontinence and retrograde ejaculation.

The management of urethral lesions in pelvic trauma survivors must focus on minimising the risk of future sequelae. There is still controversy surrounding its initial management in paediatric urology. Once urinary derivation by suprapubic catheterisation (vesicostomy) has been done, it is difficult to perform primary endoscopic realignment (the main approach in adults)1–4 in young children due to lack of experience and of paediatric cystoscopic equipment (including a flexible cystoscope). Urethral stricture is the natural course of full ruptures, leading to difficult urination and often to post-void residual urine, lithiasis, urinary retention, and urinary tract infections. The rate of stricture recurrence is high for the endoscopic approach, and is also considerable after open urethroplasty (15–68%).1–3

Another possible sequela, urinary retention, occurs less frequently (3–24%), although it is the complication that has the greatest impact on the quality of life of a child or adolescent that has survived pelvic trauma.1–5 Last of all, ED is also a very prevalent sequela and it has only been studied recently in patients that presented with posterior urethral injury during childhood.2,6 In a recent retrospective study of 60 patients that had urethral injuries in childhood, 47% exhibited ED (severe in 82% of them), mainly due to damage to vascular structures (vasculogenic aetiology).6

Posterior urethral injuries must not be underestimated in cases of pelvic trauma in children. While these injuries do not affect initial mortality, their treatment can be unsuccessful and impact the long-term quality of life in adulthood.

Please cite this article as: Fernandez Ibieta M, Bujons Tur A, Caffaratti Sfulcini J, Ayuso González L, Villavicencio H. La larga marcha de los traumatismos uretrales. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;82:192–193.