In the past few years, antimicrobial resistance has increased, becoming a serious public health problem. The irrational use of antimicrobials is one of the main contributors to antimicrobial resistance. The paediatric population is not free from this problem, as antimicrobials are widely prescribed in this age group, often inappropriately.

The introduction of antimicrobial stewardship programmes (ASPs) has proven crucial in curbing the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. At the international level, the need to develop specific paediatric ASPs has been recognised on account of the differences between adult and paediatric patients as concerns infection and approaches to diagnosis and treatment. For this reason, paediatric ASPs should be multidisciplinary programmes led by paediatric infectious disease specialists and use specific paediatric indicators (such as days of treatment, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in the paediatric population, or clinical indicators) to help identify areas of improvement and develop effective targeted interventions. On the other hand, the support and leadership of the pertinent scientific societies are also essential.

The purpose of this document is to present the position of the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases) concerning the implementation of paediatric ASPs in hospitals in Spain and to provide tools to facilitate their application in hospitals throughout the regional health care systems in the country.

Durante los últimos años ha habido un aumento en la aparición de resistencias antimicrobianas, lo cual supone un grave problema de salud pública. El mal uso de antimicrobianos es un factor determinante en su desarrollo. La población pediátrica no queda exenta de dicha problemática ya que la prescripción de antibióticos en pediatría es elevada y en muchas ocasiones inadecuada.

La incorporación de los programas de optimización de uso de antimicrobianos (PROA) ha resultado ser una medida crucial para disminuir el riesgo en la aparición de resistencias antibióticas. A nivel internacional se reconoce la necesidad de crear PROAs específicos en pediatría (PROA-P) debido a las diferencias existentes entre pacientes adultos y pediátricos en referencia a las infecciones, así como al abordaje tanto diagnóstico como terapéutico de las mismas. Por esta misma razón, los PROA-P deben ser programas multidisciplinares liderados por especialistas en infecciones pediátricas y trabajar con indicadores específicos pediátricos (DOT, patrones de sensibilidad antibiótica de población pediátrica, indicadores clínicos…) que permitan detectar puntos de mejora y establecer estrategias dirigidas eficaces. Por otro lado, es imprescindible el apoyo y liderazgo por parte de las distintas sociedades científicas implicadas.

El objetivo de este documento es dar a conocer el posicionamiento de la Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP) sobre la implementación de los PROA pediátricos hospitalarios en nuestro territorio así como aportar herramientas que ayuden en la aplicación de dichos programas en los diferentes hospitales de las distintas regiones sanitarias del país.

The increase of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an important public health problem that also affects the paediatric population. The development of AMR is multifactorial, and the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials plays a key role in it.1

Antibiotics are the most frequently used drugs in the paediatric population, and in recent years there has been an increase in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat infections for which they are not indicated.2 At the hospital level, the last point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use in Europe conducted by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) found that 38% of paediatric inpatients were treated with at least 1 antibiotic during their hospital stay. Stratified by age, the percentage of patients aged 1–5 years treated with antibiotherapy rose to 49%, considerably higher compared to the adult population (which did not exceed 38% in any age group).3

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospital-based paediatric careThe implementation of antibiotic stewardship programmes (ASPs) in health care has become one of the main strategies to minimise the risk of AMR development, prolonging the useful life of existing antimicrobials. They are multidisciplinary programmes aimed at promoting the rational use of antimicrobials. The goals of ASPs are to improve clinical outcomes in patients with infections, minimise the adverse events associated with antimicrobial use (including AMR) and guaranteeing the use of cost-effective treatments.4 For more than 10 years, scientific societies such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) or American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have set the development of specific ASPs for paediatric patients as a priority.1 This urgency stems from the substantial and inadequate consumption of antibiotics in this age group, the differences in the aetiology and clinical presentation of infections in children, the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the agents used in the paediatric population, the incidence of infections caused by drug-resistant pathogens and the lesser evidence on the efficacy and safety of some antimicrobials in infants and children.

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes are health care quality programmes that must be developed in the framework of the Committee on Infections and Antibiotherapy Policy and implemented by the health care services administrators and authorities at the institutional level. Effective implementation requires unambiguous commitment on their part. Leadership is also required from the different scientific societies and specialists in paediatric infectious diseases. In 2012, the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC, Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology), the Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria (SEFH, Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy) and the Sociedad Española de Medicina Preventiva, Salud Pública e Higiene (SEMPSPH, Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health and Hygiene) developed a document to raise awareness in health care professionals of the need to implement these programmes and provide a toolkit for the implementation of ASPs adapted to different social and health care circumstances.4

In 2022, a more specific document was published that included the paediatric perspective contributed by the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases).5 As regards individual leadership, it is crucial for paediatric ASPs (pASPs) to be developed and led by specialists in paediatric infectious disease, establishing an antibiotic stewardship (AS) programme/team including microbiologists, pharmacists, specialists in preventive medicine, nurses and prescribers. If the volume of paediatric services of a facility is too small to implement a specific paediatric programme, a paediatrician with expertise in rational antimicrobial use should be included in the AS programme/team of the facility to address specific paediatric indicators.1 In addition, the Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices) developed the National Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance to establish a national framework for the fight against AMRs. This plan outlined strategies for the implementation of ASPs and set criteria for the accreditation of AS programmes/teams based on the assessment of established excellence standards.

Although in recent years there has been an increase in specific paediatric antimicrobial stewardship interventions, it is absolutely necessary to continue disseminating knowledge through documents to, in turn, guide the implementation of pASPs in hospitals and health care service areas throughout Spain.

Antimicrobial stewardship strategiesThese are the strategies implemented in the framework of an ASP to achieve the objectives of the programme. Table 1 summarises the main types.1,6,7 Based on their time of application in relation to the antibiotic prescription, they can be classified into pre-prescription and post-prescription strategies.

Types of antimicrobial stewardship strategies in paediatric care.6,9

| Type of action | Characteristics | Timing of implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Passive and active education | Training and education activities on antimicrobial stewardship concepts and principles. Passive: an instructor provides information (theoretical sessions, educational materials, alerts in the intranet) Active: knowledge acquired through hands-on experience of prescriber (practical workshops, simulations). | Can be applied at any time in the prescription process (before, during and after). Must be applied consistently to have a long-term impact. |

| Clinical guidelines and management algorithms | Standardized, evidence-based multidisciplinary management pathways outlining appropriate sequences of clinical interventions with defined time frameworks, targets and expected outcomes. They include:Development of institutional guidelines. Development of cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility test data reports. Development of a protocol to detect and rule out antimicrobial allergies and for antimicrobial desensitization. Integration of clinical decision support systems for prescribing. Holding educational meetings and issuing reminders in staff meetings with distribution of written resources. | Developed and available before prescribing. |

| Restrictive | Restriction of certain antimicrobials or antimicrobial classes with a high ecological impact, requiring pre-authorization of an expert advisor for their use. Since it can increase the use of antimicrobials that are not restricted, shifting patterns of antimicrobial resistance, it is usually reserved for outbreaks or situations in which early results are required. | Antimicrobial restriction is defined before prescribing and take effect during prescription |

| Imposed | An expert is given full authority to modify prescriptions to optimize antimicrobial treatment. This approach is poorly accepted by prescribers, so it is only recommended in emergencies. | After prescription. |

| Consensus-based/educational | An expert reviews existing antimicrobial treatments with the prescribers to reach a consensus on the best possible treatment. At present, these strategies are the most widely accepted, with a stronger and longer-term impact on prescribers. They are commonly referred to as prospective audit and feedback, specialist consultation or educational interview. | After prescription. |

Actions implemented before antibiotic prescribing help optimise antimicrobial use. They usually require few resources and have a significant impact. Since they are easy to implement, they should be included as basic interventions in any ASP.

EducationAn essential component of any ASP8 whose goal is not only to reduce antimicrobial use but also, when antimicrobial use is indicated, to ensure the use of the appropriate antimicrobial at the correct dose through the correct route and with the optimal duration.8 Educational activities increase knowledge and modify prescribing practices.

Education on the rational use of antimicrobials should be provided to all health care professionals involved in antimicrobial prescription, dispensation and administration, including continuing education programmes for practising professionals and the integration of the subject in the educational curriculum of medical students, interns and residents. Educational activities should be offered at regular intervals to enhance knowledge acquisition.

There are different types of educational interventions, which can complement one another, that may be classified into passive and active education activities (Table 1).9 The discussion of practical aspects in the management of specific cases (whether real or simulated), which actively engages participants, tends to have a greater impact compared to passive learning activities.

Emerging technologies are a key resource in education, allowing delivery of online trainings, which can be attended remotely by a large number of participants, and the development of software applications for electronic devices or websites with useful information.

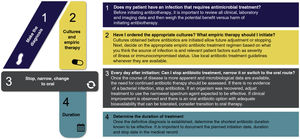

Table 2 presents the educational goals and the skills to be addressed in these interventions.8 The 4 moments of antibiotic prescribing (Fig. 1) is an educational approach that has proven very useful.10

Antimicrobial stewardship education objectives and competenciesa.

| Area | Educational objectives and competencies |

|---|---|

| Antimicrobial resistance | • To know the epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance: national, regional and local prevalence for the main microorganisms. |

| • To know the importance of preventing transmission of drug-resistant microbes and integrate infection control principles in everyday practice. | |

| Diagnosis of infectious diseases | • Clinical assessment of patients with suspected infection. |

| • Identification of individuals that would benefit from empiric antibiotherapy versus those in whom antibiotherapy does not need to be initiated. | |

| • To know the epidemiology of infectious diseases in different age groups. | |

| • Appropriate ordering of available microbiological tests. | |

| • Adequate collection, transport and processing of microbiological samples. | |

| • Correct interpretation of microbiological test results. | |

| Antimicrobial treatment and principles of infectious disease management | • To know the available antimicrobials and whether they are authorized for use in the paediatric population, as well as their ecological impact and strategic value. |

| • Optimize antimicrobial selection and dosing in empiric therapy (basic principles of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics). | |

| • Appropriate antimicrobial selection and dosing in targeted therapy. | |

| • Optimize the use of sequential therapy. | |

| • Appropriate duration of antimicrobial therapy. | |

| • Adequate use of antibiotic prophylaxis: adequate selection of patients in whom it is indicated as well as the agents to use, their dose, schedule and duration of treatment. | |

| • Evaluation and treatment of patients with antimicrobial allergy. | |

| Information management | • Document the indication and prescription of antibiotherapy and its expected duration in the health records. |

| • Inform patient and the family about decisions regarding antibiotherapy (both when it is and it is not prescribed). | |

| • Manage the expectations of patients and families regarding antimicrobial prescription. | |

Adapted from the document of the National Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance, “Herramientas e intervenciones educativas a profesionales sanitarios”, 2017.8

Four moments of antibiotic decision making*.

*Adapted from Tamma PD (2019)10 and “Four Moments of Antibiotic Decision Making” (https://www.ahrq.gov/antibiotic-use/acute-care/four-moments/index.html).

Antimicrobial treatment guidelines are one of the key tools for the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship strategies.11 It is useful for centres to have local guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of the main infectious diseases, developed by a multidisciplinary team with input of the different specialities and departments involved in patient care to guarantee adequate adherence. Recommendations should be adapted to local microbiological data, taking into account the prevalence of AMR in the selection of treatment.1,4

Guidelines should address both empiric and targeted therapy, alternatives to be used in the case of drug allergies, the duration of treatment and recommendations for transition to oral therapy, dosing and dose adjustment based on renal or liver function. It is also essential to establish protocols for surgical prophylaxis, as this is one of the most frequent indications for antibiotherapy in the hospital setting.

A system should be established to disseminate guidelines, which should be easily accessible (for instance, through the intranet, brochures, mobile applications, etc). It is also important to develop a plan for the periodic review and updating of the guidelines to ensure that recommendations are based on the best available evidence. Guidelines should include recommendations for the management of both community-acquired and health care-related infections.

Guidelines can also be used as a reference to assess the appropriateness of antimicrobial treatment practices. Ideally, local guidelines would be used for this purpose (national guidelines adapted to local epidemiology). If not available, it is possible to use international guidelines, choosing those developed in geographical areas closer to the location of the centre with a greater similarity in epidemiological trends.

Cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility reportsAlso known as cumulative antibiograms, they are reports produced periodically by departments of microbiology that include the percentage of isolates susceptible to specific antibiotics for a selection of microorganisms.12 These reports can be used for several purposes: i) monitoring the prevalence of drug-resistant microorganisms; ii) guiding the development of antimicrobial treatment recommendations adapted to local epidemiology; iii) guiding decision-making regarding empiric antibiotherapy in specific situations when microbiological tests results are still not available.13

The microorganisms and antibiotics to be included in these reports should be selected based on epidemiological criteria, prioritising those that are most relevant due to their frequency and clinical impact. In Spain, the recommended clinical breakpoints to define antimicrobial susceptibility categories are those established by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), which are also revised periodically, and reports should include the percentage of isolates that were susceptible, susceptible with increased exposure and resistant. Reports should only include isolates obtained from clinical samples, excluding samples obtained in the context of epidemiological and environmental surveillance.

It is recommended that these reports be made at least on an annual basis. In addition, a plan must be made for their dissemination, and the reports should be easily accessible. It is also recommended that these reports include data on the surveillance of the phenotypes associated with drug resistance mechanisms, as opposed to being limited to raw data on AMR.

Since epidemiological trends are different in children and adults, antibiograms should be stratified by age group.14 Similarly, in hospitals with specialized paediatric units and a high volume (paediatric intensive care unit, paediatric cancer unit, neonatal unit…), specific antibiogram analyses should be made at the unit level. In facilities with a reduced number of paediatric patients, if the total number of isolates for a species or group is less than 30, data for several years or for different units could be pooled. An alternative for community-acquired infections would be to pool data of different laboratories in the same geographical area.

Antimicrobial allergiesConfirmed or suspected antimicrobial allergy is frequent and affects the selection of alternative antimicrobials, which are often less effective or more toxic than the first-line agent and associated with poorer patient outcomes.14 Although the prevalence of self-reported β-lactam allergy in children ranges from 1.7% to 5.2%, only a minority of these children are truly allergic.15

A thorough history must be taken in these patients, assessing their characteristics and risks, to select the best possible antimicrobial. Allergy testing, which can be performed at any age, is key to explore the suspicion and establish the type of allergy. Antimicrobial desensitization may be required in some cases if it is important to adhere to the first-line antimicrobial agent.

Clinical decision support systems for prescribingClinical decision support systems for prescribing integrated in electronic prescription systems are increasingly available in hospitals.4 The most frequent tools are the integration of infectious disease protocols in pharmaceutical prescription applications that select the first-line antimicrobial(s) based on local guidelines and calculate weight-based doses, including the maximum dose. This prevents prescribing errors and improves adherence to institutional guidelines.

Post-prescription strategiesThe purpose of these interventions (Table 1) is the dynamic evaluation of administered treatments, assessing the adherence to institutional guidelines.1,6,7

Prospective audit and feedback (PAF) or educational interviewThey are consensus-based strategies that are the cornerstone of most ASPs due to their significant acceptance and impact on prescribers.1,6,7,16 They require the collaboration of the AS programme/team and the prescriber to assess and select the best antibiotic option for the patient.1,6,7,16 For this strategy to be accepted, there must be mutual respect and trust between the involved parties, allowing each to contribute their knowledge in the best interests of the patient with the understanding that optimised treatment will improve clinical outcomes and reduce the deleterious effects of inappropriate antimicrobial use. The specialist providing guidance must gather as much information as possible about the patient and identify key aspects to optimise treatment.1,6,7,16

Prospective audit and feedback strategies can be implemented at any point in the course of treatment. They can be general or targeted to specific antimicrobial agents or groups, hospital units or departments or diseases. Implementation of PAF at 5 key timepoints has been proposed: at the start of treatment, at 12–24 h (early empiric therapy), at 24–48 h (late empiric therapy), at 48–72 h (targeted therapy) and at 5–7 days (end of treatment or adjustment of duration if prolonged treatment is needed).6,17 Five key questions must be addressed in any PAF, applying the general principles of ASP (Table 3).7,18,19Fig. 2 presents their application in the patient evaluation and prescribing process.

Key questions that apply the general principles of antimicrobial stewardship programmes.

| Question | Description |

|---|---|

| Is the treatment indicated in the patient? | The indication of antibiotic treatment should be assessed, discontinuing treatment in situations in which it will not be beneficial to the patient (viral infections, non-infectious disease).1,7,19 If the likelihood of bacterial infection is low or the disease is not life-threatening and does not pose a risk of severe complications, antibiotherapy can be delayed.6,17 Antibiotherapy should be initiated promptly if a severe bacterial infection is suspected.6,17 The indication of treatment is defined through the assessment of6,17: |

| A. Clinical presentation: the diagnosis will consider the potential severity of the infection and the most common aetiologies compatible with the presentation. | |

| B. Patient age: age (newborn, infant, child, adolescent) is an essential factor to consider in the evaluation of paediatric patients, as it, in itself, defines a level of risk and which causative agents are most commonly involved in infectious diseases | |

| C. Patient risk: identification of risk factors other than age, such as immunosuppression, susceptibilities associated with underlying diseases, history of exposure. | |

| D. Rapid diagnostic tests: allow the identification of infections in which antibiotherapy could be beneficial (or alternative aetiologies not requiring it) earlier than culture.40 They include staining (Gram, Ziehl-Neelsen, auramine-rhodamine, India ink, Giemsa, etc.), direct visualization techniques (KOH, dark field, smear, etc.) and molecular antigen or nucleic acid detection tests that can be performed in different biological samples (respiratory secretions, urine, serum, cerebrospinal fluid, exudate) to identify bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites with a turnaround time ranging from a few minutes to 4–6 h.40 Determinants of pathogen drug resistance can also be detected, which help optimise treatment in the early empiric phase of treatment (eg, beta-lactamase/carbapenem resistance genes in enterobacteria and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, detection of mecA/mecC gene for identification of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus).40 Their yield may vary depending on the sample, technique used and pre-test probability, so their results must be interpreted with caution by staff with expertise in infectious diseases. | |

| Which infectious disease is suspected? | The infectious disease is identified through an anamnesis, physical examination and diagnostic tests.6,17 Its identification is crucial, as it helps establish the indication of antibiotherapy and the selection of the drug. Antimicrobials must be prescribed to treat a specific infectious disease, avoiding their indiscriminate use in pursuit of a false sense of safety in patients exhibiting an unfavourable course of disease of viral or non-infectious aetiology.6,17 |

| Which samples should be obtained for microbiological diagnosis? | Any microbiological samples required to confirm the suspected diagnosis must be collected before initiating antibiotherapy.6,17,40 Emphasis must be placed on the indication, methods of collection, preservation and transport of these samples, and the correct interpretation of microbiological results: interpretation of antibiotic susceptibility test results and identification of positive results that do not correspond to infection (contamination, colonization).40 |

| What is the most appropriate antimicrobial? | Empiric therapy is selected based on the clinical presentation and evaluation, age, risk factors and local microbiological data, establishing the most frequent pathogens and their drug-resistance patterns.1,6,17 Targeted therapy is selected based on the interpretation of the antibiogram.1,6,17 The selected antimicrobial must be the one offering the highest activity and tissue penetration at the site of infection with the narrowest spectrum and lowest toxicity possible (Fig. 2). The route of administration, dose, dose intervals and expected duration for the selected antibiotic must also be defined.1,6,17 |

| Have I implemented applicable source control measures? | Appropriate management of an infection includes adequate infection source control. Removal of any vascular access lines, catheters or other infected devices, in addition to abscess drainage are essential source control measures. Inadequate source control can result in therapeutic failure, prolonged treatment or use of unnecessarily broad-spectrum antibiotics. An uncontrolled source of infection should be suspected in patients that do not show an adequate response to appropriate treatment for their infectious disease. |

Application of antimicrobial stewardship activities in paediatric care*.

Abbreviations: IS: Infectious syndrome; IWAT, infection that warrants antimicrobial treatment; MC, microbiologically confirmed; wMC, without microbiological confirmation.

*Adapted from Goycochea-Valdivia WA, 2019 and Bielicki JA, 2017.6,17 Arrows in purple boxes indicate the time AS interventions are implemented in the prescribing process (Table 1).

1The IS, age, risk factors and rapid diagnostic tests define the probability of IWAT and the severity/life-threatening potential of the disease, based on which the decision is made whether to initiate or delay antibiotherapy.

2The IS, age, risk factors and local microbiology will be used to determine the most prevalent microorganisms (selection of agent for empiric antibiotherapy). Consider:

a. Adequate spectrum: always choose the narrowest possible spectrum to avoid increasing ecological pressure.

b. Route of administration: parenteral or oral, based on IS, patient age, enteral tolerance, intestinal absorption and concentration at the site of activity.

-Parenteral route: increased bioavailability, generally used for infections that are severe or in sites where it is difficult to achieve high concentrations.

-Oral route: generally used in mild to moderate infections or to complete the treatment of severe infections (a switch to the oral route should be considered whenever possible). In some cases, this is the only possible route. Assess for conditions that could interfere with absorption.

c. Dose: in paediatrics, it should be adjusted to the body weight or surface area. Verify the maximum recommended dose, check for situations requiring therapeutic drug monitoring, that may affect pharmacokinetics (renal function, haemofiltration, mechanical circulatory support, interactions) or in which the threshold between therapeutic and toxic concentrations is a concern (concentration-dependent antimicrobial activity).

d. Interval: may vary based on age (especially in neonates), the IS and conditions affecting drug pharmacokinetics. Consider situations in which the patient may benefit from the use of prolonged or continuous infusion (time-dependent antibiotics).

e. Duration: the duration must be specified from the start of treatment and reviewed after microbiological tests results are available. There is a growing body of evidence in support of short courses of treatment, although the evidence in paediatrics is still limited.

3Guide antibiotherapy with preliminary microbiological data.

4Determine whether the patient has an IWAT-MC, IWAT-wMC or does not have an IWAT, and act accordingly.

5Confirm adherence to the appropriate duration of treatment, checking for cases that require prolonged treatment.

Monitoring and comparison with previous data or other centres, in addition to transparent feedback, are inherent components of ASPs. There are significant differences in the monitoring of outcomes in hospitalised paediatric patients compared to adult inpatients.

Clinical indicatorsThe main indicators used are the hospital length of stay (LOS), readmission rate, mortality and AMR.7,14,20–26 Indicators used in adults may not be appropriate in children (for example, the rate of infection by Clostridioides difficile, which must be excluded from the analysis in children aged less than 2 years due to frequent carrier status).

Consumption metricsTable 4 presents the antimicrobial consumption metrics used most frequently in hospital-based paediatric care. At present, the most widely recommended antibiotic consumption metric in paediatrics is days of therapy (DOT). Ideally, these metrics should be calculated for the overall hospital and broken down by department or unit at regular intervals to be determined based on the available resources (annual, trimestral or monthly).

Frequently used indicators of antimicrobial usage in hospitals in the paediatric population.7,14,22,24

| Consumption indicator | Notes |

|---|---|

| Days of therapy (DOT)a | • Number of days that a patient receives a given antimicrobial, regardless of the dose. |

| • It is the consumption metric currently recommended for assessment of antimicrobial consumption in paediatric and neonatal patients. | |

| • It should be calculated for specific drugs, care units or patients grouped by a specific diagnosis. | |

| • Should be weighted based on health care activity, usually calculated per 100 or 1000 patient days, admissions or discharges. | |

| • Limitations: its calculation may be somewhat complex, it requires the use of electronic prescriptions and ideally dispensation records. It does not take dose into account. In neonates, it can yield results that differ from those in other age groups on account of schedules with dose intervals every 18 h or 48 hr. | |

| Prescribed daily dose (PDD) | • Usual prescribed dose of a given antimicrobial. |

| • More useful to assess adherence to protocols or the use of specific agents. | |

| • Limitations: makes comparing facilities difficult. | |

| Length of Therapy (LOT) | • Number of days of antibiotherapy, regardless of the number of antibiotics received per day. |

| • Inversely related to days without antimicrobial treatment. | |

| • Limitations: does not take into account dose intervals. | |

| Days of therapy/Length of therapy (DOT/LOT) | • Limitations: the calculation can be somewhat complex, and it does not take dose into account. |

| Defined daily dose (DDD) | • Average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. |

| • A modified weight-adjusted version may be used, calculating the average paediatric maintenance dose per day adjusted by kilogram of body weight, standardised based on the average weight in the department under consideration. | |

| • In the paediatric and neonatal population, it is preferable and necessary to use DOT | |

| • Limitations: it is affected by weight, which is highly variable in children, then is a source of significant bias in its calculation. It may overestimate antibiotic consumption in situations in which doses greater than recommended are used (multidrug resistance, critical patients, etc) | |

| Start of treatment (SOT) | • Number of patients that receive an antimicrobial, regardless of the number of drugs, their spectrum or the duration of treatment, over a given time period. |

| • Usually measured in 100 or 1000 inpatients over a specific time period. | |

| • Especially useful in the evaluation of certain diseases (eg, hospitalised patients with acute bronchiolitis receiving antimicrobial treatment). | |

| • Limitations: it does not take into account the duration of treatment, combination of agents or spectrum of activity. | |

| Transition from intravenous to oral route | • Indicator used for antimicrobials with a high bioavailability when administered orally. |

| • Usually calculated as the percentage of patients that switch to an oral antibiotic within 24 h of oral treatment being indicated based on clinical practice guidelines, and the median time elapsed from the moment the switch it is indicated to the moment it takes place. | |

| • Should be calculated for specific drugs, care units or groups of patients associated with a specific diagnosis. | |

One significant limitation of consumption metrics is that they do not take into consideration antimicrobial use appropriateness. Point-prevalence surveys are analyses of antimicrobial prescribing at specific time points to assess its appropriateness and identify opportunities of improvement and priorities for intervention. They are conducted periodically and ideally include the percentage of patients in which the indication for treatment was documented, the adherence of the prescription to established guidelines, the appropriateness of the dose based on the infectious disease and the patient weight, the duration of treatment, spurious antimicrobial allergies and adequate use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and of the oral route of administration.

Current evidenceThe key principles and strategies for developing paediatric ASP were defined years ago in several international documents.7,14,19 Since then, the evidence on the usefulness of ASPs in paediatric care has grown, although slower compared to adult care.21,27 The development of specific paediatric guidelines for empiric antibiotherapy and consultations with paediatric infectious diseases specialists have been found to have the greatest impact.

Inpatient mortality is lower in paediatrics compared to the adult population, so it is difficult to find evidence of a decrease in mortality. However, ASPs have proven to be safe, as the mortality before and after the introduction of these programmes has remained stable based on evidence of ASP strategies implementation on different neonatal28 and paediatric settings.16,23,29–31 Decreases in LOS and readmission have been the most frequently used indicators in the evaluation of pASPs.

A multicentre study conducted in children’s hospitals in the United States found an overall reduction in antibiotic use following the implementation of an AS intervention.26 Other studies in single centres have documented significant overall reductions in consumption applying PAF in restrictive or non-restrictive AS interventions.16,30,32–34 Prospective audit and feedback by itself is effective in reducing the use of antimicrobials in children, and it could achieve a long-lasting adherence to guidelines by prescribing physicians. Other authors have documented a decrease in the use of select agents or broad-spectrum antibiotics.35,36

Few studies have been conducted to assess the decrease of AMR in children. Lighter-Fisher et al.32 and Horikoshi et al.37 documented a reduction in AMR in gram-negative bacteria. Contrary to the adult population, there is a dearth of data supporting that ASPs reduce AMR in children.7

Several studies in the paediatric population have shown a significant cost reduction after the implementation of an ASP,30,34 so the allocation of medical staff to implement these interventions in paediatric care settings may be cost-effective.7

Gaps and barriersAntimicrobial stewardship programmes are interventions meant to achieve lasting changes in antimicrobial prescribing practices. Their success depends to a large extent in designing them with an understanding of social and behavioural dynamics.38 In paediatrics, antimicrobial prescription is usually founded on a far more proactive approach to treatment than to diagnosis.

The traditional argument in support of the usefulness of ASPs in the context of the global emergence of AMR is frequently not perceived by prescribers as something that directly affects their patients. However, arguments founded in maximising the reduction of the risk of adverse effects due to irrational antimicrobial use may have a more immediate impact.39 Educating the general population about these issues and the expectations and beliefs of patients and families are also important aspects.

Before an ASP is implemented, surveys and/or interviews with prescribers should be conducted to identify the key factors involved in antimicrobial prescription in everyday clinical practice. There are no universal models for the implementation of ASP guaranteeing their success. Success is achieved by designing strategies that combine the detection of opportunities for improvement, or the prescribing practices that the intervention will seek to change, with the analysis of local factors that influence decision-making in antimicrobial prescribing. The use of well-established behaviour modification techniques and the performance of evaluations during the process is recommended to understand why proposed strategies succeed or fail.

Obtaining specific paediatric consumption data is of vital importance. Therefore, implementation of the necessary metrics is of the essence. Linking hospital-based and primary care pASP, with shared and coordinated antimicrobial prescribing policies between the two levels of care, is another barrier that must be overcome.

The institutionalization of pASPs with multidisciplinary AS teams supplemented with additional specialists in the field working in coordination and using specific indicators for each paediatric speciality (intensive care, surgery, primary care, neonatology, etc) is one of the measures that can favour the future integration of these quality improvement programmes in our institutions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Emilia Cercenado Mansilla (Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. CIBERES, Biomedical Research Centre Network on Respiratory Diseases, CB06/06/0058, Madrid), Cristina Epalza Ibarrondo (Section on Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Paediatrics. ASP Group. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre [IMAS12], Madrid), Aurora Fernández Polo (Department of Pharmacy, Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona), Marta García Ascaso (Paediatric Infectious Disease Unit, Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid), Cristian Launes Montaña (Department of Paediatrics. Hospital Santa Joan de Déu, Barcelona. Working Group on Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona. CIBER Research Centre Network on Epidemiology and Public Health [CIBERESP], Madrid), Guillermo Martín-Gutiérrez (Infectious Diseases, Microbiology and Preventive Medicine Clinical Unit, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Infectious Disease Working Group, Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla [IBiS]. Universidad de Sevilla), Francisco Moreno Ramos (Department of Hospital Pharmacy. Instituto de Investigación del Hospital Universitario La Paz [IdiPAZ], Madrid), José Tomás Ramos Amador (Department of Paediatrics, Universidad Complutense-Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos [IdISSC], CIBER Research Centre Network on Infectious Diseases [CIBERINFEC], Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid), Carlos Rodrigo Gonzalo de Liria (Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol and Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona), María del Carmen Suarez Arrabal (La Marina Primary Care Centre, Santander. Primary Care System Administration, Department of Health of Cantabria), Eneritz Velasco Arnaiz (Infectious Disease Unit, ASP-Sant Joan de Déu. Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona).

The members of the PROA Working Group of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (SEIP) are presented in Appendix 1.