The prevalence of malnutrition among infants with congenital heart disease (CHD) is high. Early nutritional assessment and intervention contribute significantly to its treatment and improve outcomes. Our objective was to develop a consensus document for the nutritional assessment and management of infants with CHD.

Material and methodsWe employed a modified Delphi technique. Based on the literature and clinical experience, a scientific committee prepared a list of statements that addressed the referral to paediatric nutrition units (PNUs), assessment, and nutritional management of infants with CHD. Specialists in paediatric cardiology and paediatric gastroenterology and nutrition evaluated the questionnaire in 2 rounds.

ResultsThirty-two specialists participated. After two evaluation rounds, a consensus was reached for 150 out of 185 items (81%). Cardiac pathologies associated with a low and high nutritional risk and associated cardiac or extracardiac factors that carry a high nutritional risk were identified. The committee developed recommendations for assessment and follow-up by nutrition units and for the calculation of nutritional requirements, the type of nutrition and the route of administration. Particular attention was devoted to the need for intensive nutrition therapy in the preoperative period, the follow-up by the PNU during the postoperative period of patients who required preoperative nutritional care, and reassessment by the cardiologist in the case nutrition goals are not achieved.

ConclusionsThese recommendations can be helpful for the early detection and referral of vulnerable patients, their evaluation and nutritional management and improving the prognosis of their CHD.

La tasa de desnutrición entre los lactantes con cardiopatías congénitas (CC) es elevada. Una evaluación e intervención nutricional tempranas ayudan a su tratamiento y mejoran el pronóstico. El objetivo fue elaborar un documento de consenso para la evaluación y el tratamiento nutricional del lactante con CC.

Material y MétodosSe utilizó una técnica Delphi modificada. En base a la literatura y a su experiencia clínica, un comité científico elaboró un listado de afirmaciones que abordaban la derivación a Unidades de Nutrición Pediátrica (UNP), la evaluación y el manejo nutricional de los lactantes con CC. Especialistas en cardiología pediátrica, y gastroenterología y nutrición pediátrica evaluaron el cuestionario en 2 rondas.

ResultadosParticiparon 32 especialistas. Tras dos rondas de evaluación, se consensuaron 150 de 185 ítems (81%). Se determinaron patologías cardiacas de bajo y alto riesgo nutricional y factores asociados cardíacos o extracardíacos que confieren riesgo nutricional alto. Se elaboraron recomendaciones para la evaluación y seguimiento en unidades de nutrición y sobre el cálculo de los requerimientos nutricionales, el tipo de nutrición y la vía de administración. Se enfatiza la necesidad de un tratamiento nutricional intensivo en el preoperatorio, del seguimiento por la UNP en el postoperatorio cuando se haya necesitado intervención preoperatoria, y de la reevaluación por el cardiólogo cuando no se alcancen los objetivos nutricionales.

ConclusionesEstas recomendaciones pueden ser de ayuda para la detección precoz y derivación temprana de población vulnerable, su evaluación y tratamiento nutricional y para mejorar el pronóstico de su CC.

Congenital heart diseases (CHDs) constitute the most frequent group of congenital malformations, with an incidence of 8–12 cases per 1000 live births.1 Approximately one third of affected children have haemodynamically significant CHD and are likely to require intervention (open surgery, catheterization or pharmacological treatment).2 Most infants with CHD have normal weights at birth but develop nutritional and growth deficiencies in the first months of life, depending on the type of CHD.3 Infants with mild CHD usually have normal growth and development,4 but infants with moderate or severe CHD are at risk of nutritional problems that may affect development and growth and associated with an increased morbidity and mortality.5 The prevalence of malnutrition in children with CHD ranges from 15% to 64%.6

The cause of these nutritional abnormalities is multifactorial, including both cardiac and extracardiac factors involving important aspects such as metabolic demand, energy expenditure, intake or intestinal absorption.3 Early identification and prompt and appropriate intervention with frequent assessments are key to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with malnutrition.7 However, current nutritional assessment and management practices in infants with CHD are heterogeneous and vary between care settings and hospitals.7,8 Guidelines for the assessment and nutrition of critically ill children have been proposed by scientific societies in the fields of nutrition, paediatric cardiology or intensive care, but their recommendations are not homogeneous and do not focus on infants with CHD.5,8–14

The aim of this project was to establish consensus recommendations for the referral to the paediatric nutrition unit (PNU), the assessment and estimation of nutritional needs and nutrition therapy of infants with CHD in a multidisciplinary approach.

Material and methodsWe used a modified Delphi method following the RAND/UCLA recommendations.15,16 The first step was to gather a scientific committee comprised of 10 members of the Spanish societies of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition (Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica, SEGHNP) and paediatric cardiology and congenital heart diseases (Sociedad Española de Cardiología Pediátrica y Cardiopatías Congénitas, SECPCC). Following a literature search, the committee drafted statements or proposals regarding controversial aspects of referral, assessment, need estimation and nutrition therapy of infants with CHD.

Thirty-two panellists were invited to participate in the study. They were specialists in paediatric nutrition and paediatric cardiology with years of experience in the field of CHD. All participated in the 2 Delphi rounds.

Literature searchWe conducted a literature search in the PubMed database using the following terms: heart defects, congenital; nutritional status; nutrition therapy; nutritional support; nutrition assessment; enteral nutrition; parenteral nutrition; nutrition disorders; malnutrition. We made a qualitative assessment of the literature, selecting articles in Spanish and English dealing with the management of CHD in children with particular emphasis on clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and recent reviews. We also performed searches in the websites of the following scientific societies to find CPGs: Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP), SECPCC, Sociedad Española de Nutrición Clínica y Metabolismo (SENPE), SEGHNP, European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC), Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society (PCICS) and National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC).

Panellist selectionIn a second phase, a panel of experts on paediatric cardiology and paediatric gastroenterology and nutrition was selected for the task of evaluating proposed statements. The panellists were selected by the scientific societies they were affiliated with on the basis of their expertise and knowledge of or involvement in CHD.

Evaluation of proposed statements and consensus criteriaThe questionnaire was sent to the panellists to be completed online in two rounds. Between rounds, it was possible to edit confusing statements. Panellists rated statements by means of a 9-point Likert scale (1: completely disagree; 9: completely agree). Ratings were grouped into 3 categories (1–3: disagree; 4−6: neither agree nor disagree; 7–9: agree).

To consider that consensus had been reached in agreeing or disagreeing with an item, the median of the ratings by the panellists had to be within the 7–9 points or the 1–3 points range, respectively. In addition, the number of panellists that voted outside the 1–3 or 7–9 ranges had to be less than 1/3 of the total and the interquartile range had to be less than 4. Items for which a consensus was not reached in the first round were subjected to a second evaluation round, the results of which were analysed with the same method used in the first round. Panellists were informed of the results of the first round before participating in the second round. The results are summarised in tables available in the supplemental material (Appendix B, Tables S1–S4).

ResultsIn the first round, the panel reached a consensus in agreeing with 143 items, and in the second round, it reached a consensus in agreeing with an additional 7 items. After the two Delphi rounds, a consensus was reached on 150 of the 185 proposed items (81%), in agreement in every case (Appendix B, Tables S1–S4).

General aspects of nutrition in children with CHDPanellists considered that patients with CHD were a group with particular nutritional risk requiring specific assessment, and whose nutritional needs depend on the type of cardiac lesions and clinical significance. They also agreed that children with CHD require periodic assessments of their nutritional status in order to detect delays in growth early and allow intervention, and that recommendations for the nutritional management of these children need to be established to improve nutritional status before surgery (Appendix B, Table S1).

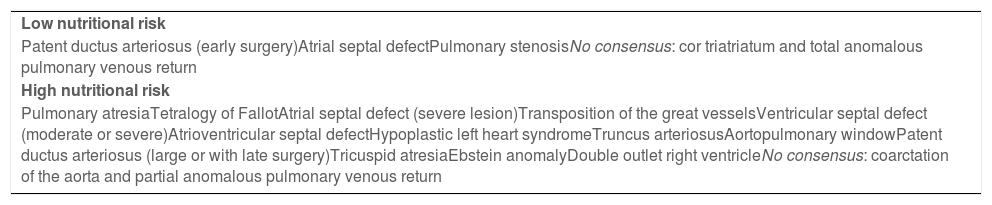

Identification and referral of vulnerable individualsIn this set of proposals, panellists reached a consensus on the CHDs and associated factors associated with a low or high nutritional risk at diagnosis (Tables 1–2) and the criteria for referral to nutrition services (Table 3). The panel considered that patent ductus arteriosus (in the case of early surgical repair), atrial septal defect and pulmonary stenosis carry a low nutritional risk. The diseases considered to carry a high nutritional risk were complex CHDs and moderate or severe cardiac shunts, including aortopulmonary window.

Congenital heart diseases associated with low or high nutritional risk at diagnosis.

| Low nutritional risk |

| Patent ductus arteriosus (early surgery)Atrial septal defectPulmonary stenosisNo consensus: cor triatriatum and total anomalous pulmonary venous return |

| High nutritional risk |

| Pulmonary atresiaTetralogy of FallotAtrial septal defect (severe lesion)Transposition of the great vesselsVentricular septal defect (moderate or severe)Atrioventricular septal defectHypoplastic left heart syndromeTruncus arteriosusAortopulmonary windowPatent ductus arteriosus (large or with late surgery)Tricuspid atresiaEbstein anomalyDouble outlet right ventricleNo consensus: coarctation of the aorta and partial anomalous pulmonary venous return |

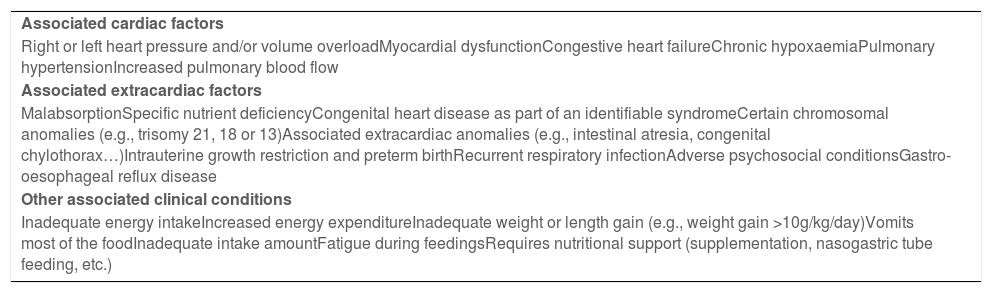

Factors associated with congenital heart diseases that carry a high nutritional risk.

| Associated cardiac factors |

| Right or left heart pressure and/or volume overloadMyocardial dysfunctionCongestive heart failureChronic hypoxaemiaPulmonary hypertensionIncreased pulmonary blood flow |

| Associated extracardiac factors |

| MalabsorptionSpecific nutrient deficiencyCongenital heart disease as part of an identifiable syndromeCertain chromosomal anomalies (e.g., trisomy 21, 18 or 13)Associated extracardiac anomalies (e.g., intestinal atresia, congenital chylothorax…)Intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birthRecurrent respiratory infectionAdverse psychosocial conditionsGastro-oesophageal reflux disease |

| Other associated clinical conditions |

| Inadequate energy intakeIncreased energy expenditureInadequate weight or length gain (e.g., weight gain >10g/kg/day)Vomits most of the foodInadequate intake amountFatigue during feedingsRequires nutritional support (supplementation, nasogastric tube feeding, etc.) |

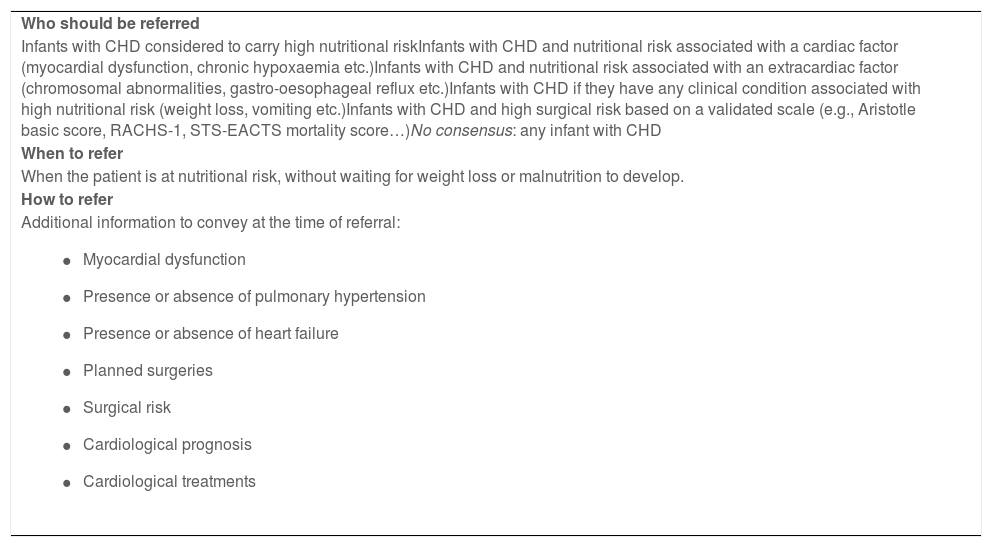

Recommendations for the referral of infants with CHD to nutrition services.

| Who should be referred |

| Infants with CHD considered to carry high nutritional riskInfants with CHD and nutritional risk associated with a cardiac factor (myocardial dysfunction, chronic hypoxaemia etc.)Infants with CHD and nutritional risk associated with an extracardiac factor (chromosomal abnormalities, gastro-oesophageal reflux etc.)Infants with CHD if they have any clinical condition associated with high nutritional risk (weight loss, vomiting etc.)Infants with CHD and high surgical risk based on a validated scale (e.g., Aristotle basic score, RACHS-1, STS-EACTS mortality score…)No consensus: any infant with CHD |

| When to refer |

| When the patient is at nutritional risk, without waiting for weight loss or malnutrition to develop. |

| How to refer |

Additional information to convey at the time of referral:

|

CHD, congenital heart disease.

The following cardiac factors were considered to be associated with a high nutritional risk: pressure and/or volume overload, myocardial dysfunction, congestive heart failure, chronic hypoxaemia, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary overflow. Among the extracardiac factors and other clinical conditions that could be considered to be associated with a high nutritional risk, the panel reached a consensus for intestinal malabsorption, intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity, inadequate energy intake or increased energy expenditure, among others.

As regards the criteria for referral to the PNU, the panel agreed that referral is required in infants with CHD considered to carry a high nutritional risk (Table 1), with any risk factor (cardiac or extracardiac) or clinical condition associated with high nutritional risk (Table 2), or with CHD and high surgical risk established by means of a validated scale. In patients with nutritional risk, referral need not be contingent on the development of malnutrition or weight loss.

Nutritional assessment and follow-upThis section was devoted to establishing consensus on the information that must be documented in the health record (such as changes in the infant weight and height gain charts, presence of fatigue or increasing cyanosis during feedings, symptoms associated with intake, etc.) and the nutritional assessment of infants with CHD managed in a paediatric nutrition clinic, among which anthropometric measurements and assessment of warning signs of cardiac failure and undernutrition are essential. The panel agreed on the diagnostic tests that needed to be performed, such as kidney and liver function tests, iron panels, and measurements of electrolyte, albumin, prealbumin and thyroid hormone levels, among others (Table 4). The panel agreed on the application of criteria based on percentiles or z scores of indices including weight-for-height, weight-for-age and height-for age to establish the nutritional status of the patients.

Recommendations on the information to document and tests to order in the assessment of infants with CHD in the department of nutrition.

| Health record | Nutritional assessment* | Diagnostic tests |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy dataAnthropometry at birthSocioeconomic factorsWeight and height gain chartsGrowth velocityConcomitant medicationDetailed dietary questionnaireAppetiteStrength and duration of suckFatigue and/or increasing cyanosis during feedingPhysical activity and quality of restAssociated symptoms (e.g. vomiting, diarrhoea, recurrent infection, etc.) | WeightLength or heightWeight-for-height percentileHead circumferenceArm circumferenceBody mass indexPercentage of expected weight-for-height (Waterlow classification)Heart failure signsUndernutrition warning signsSome form of assessment of body compositionOther measurements for which consensus was not reached: subscapular skinfold, chest circumference, waist circumference, triceps skinfold, McLaren index, Quetelet indices | Oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry)Complete blood countKidney functionLiver functionElectrolytes (sodium, potassium)Ionised calciumIron metabolismTotal proteinAlbuminPrealbuminThyroid hormone levelsOther tests for which consensus was not reached: lipid panel, immunoglobulins, IGF-1, retinol-binding protein, fibronectin, water-soluble vitamins (folic acid and vitamin B12), fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E and K), micronutrients (zinc, copper, magnesium, etc.), α1-antitripsin in stool, faecal elastase, quantitative faecal fat test, immune cell function tests |

CHD, congenital heart disease.

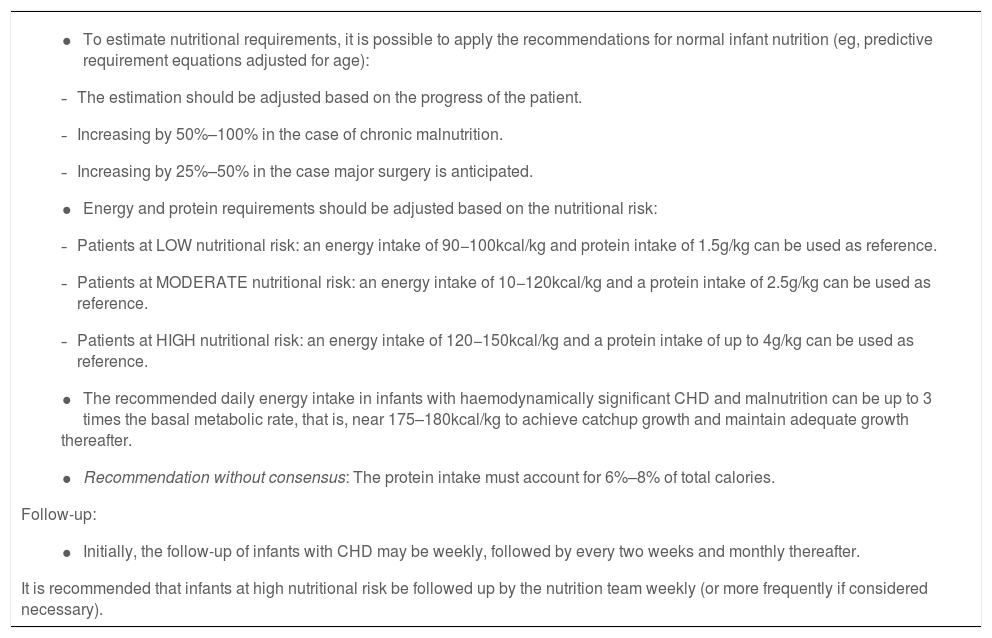

As regards the estimation of nutrient requirements (Table 5), panellists agreed that the nutritional recommendations for healthy infants could be applied making adjustments based on the progress of the patient, for instance, with increases of 50%–100% in the case of chronic undernutrition or of 25%–50% if major surgery is anticipated. Energy and protein requirements should also be adjusted based on the level of nutritional risk. An intake of 90–100kcal/kg and 1.5g protein/kg could serve as reference in patients at low nutritional risk, an intake of 110–120kcal/kg and 2.5g protein/kg in patients at moderate nutritional risk, and an intake of 20–150kcal/kg and up to 4g protein/kg in patients at high nutritional risk. The recommended energy intake in infants with haemodynamically significant CHD and malnutrition could be as high as 3 times the basal metabolic rate.

Recommendations regarding the estimation of the nutritional requirements and the follow-up of infants with CHD.

|

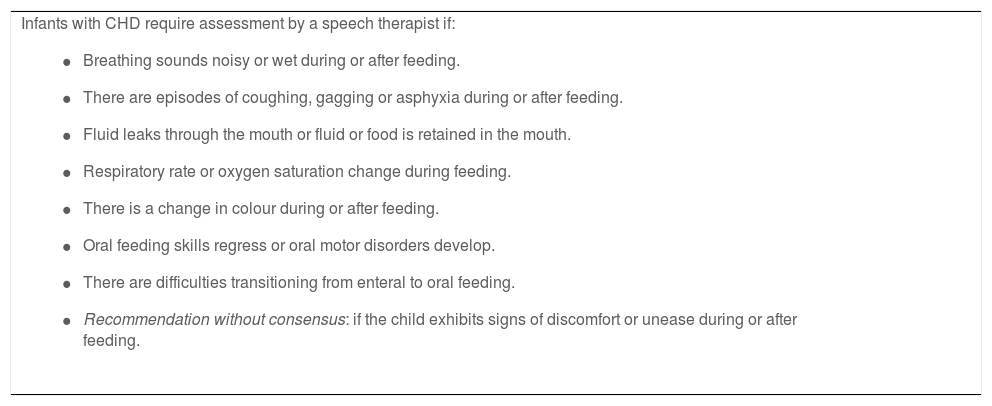

On the other hand, the recommended follow-up in infants with CHD (Table 5) could be weekly at first, followed by follow-up every 15 days and then monthly. In the case of high nutritional risk, the recommended frequency of follow-up is of at least once a week. Lastly, the panel reached a consensus on the clinical criteria for referral to speech therapy (Table 6).

Recommendations regarding the need of assessment by a speech therapist.

Infants with CHD require assessment by a speech therapist if:

|

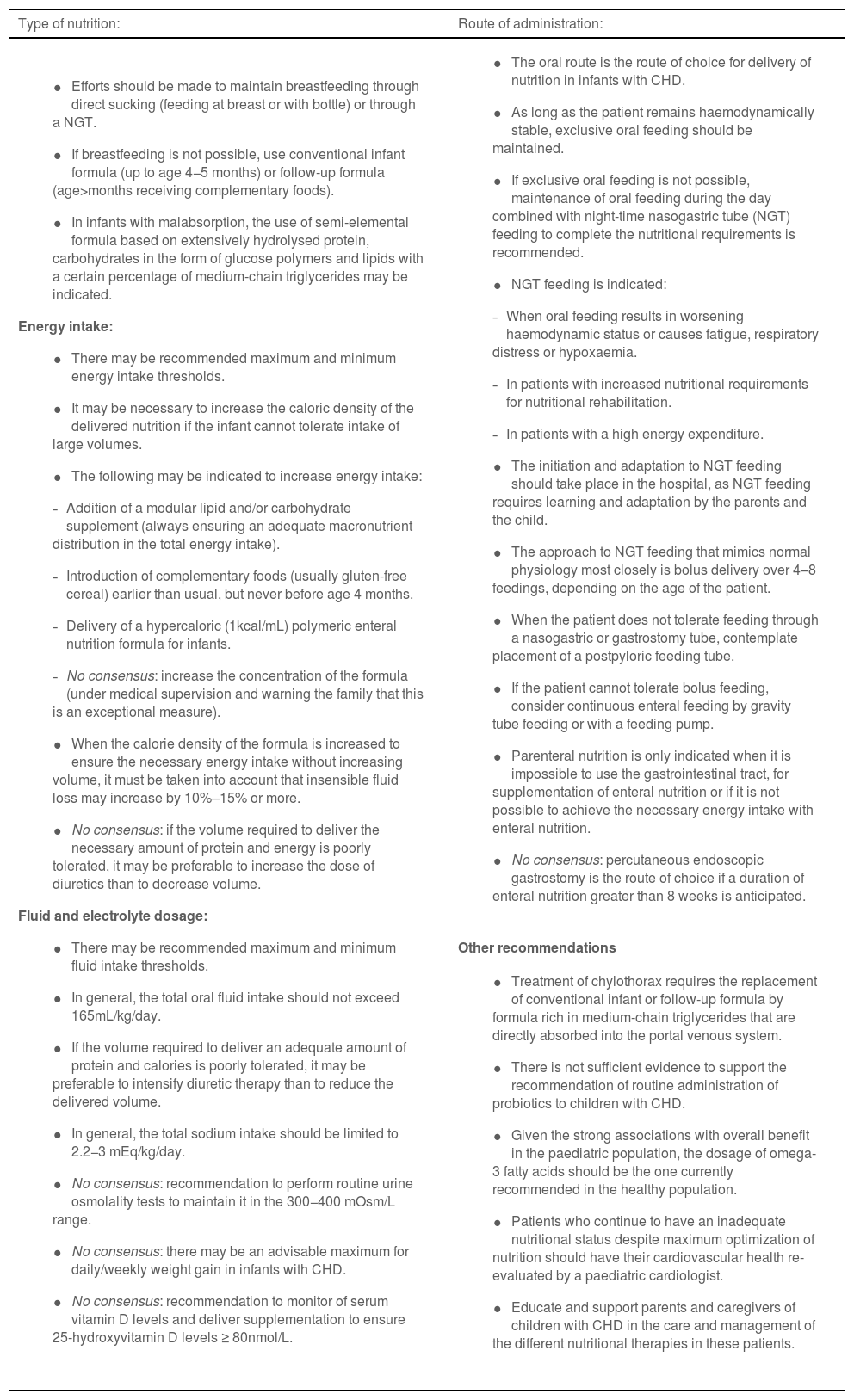

The panel agreed by consensus on recommendations regarding nutritional support and the route of administration (Table 7). Efforts should be made to maintain breastfeeding. When not possible, conventional infant or follow-up formula should be used. If the child has malabsorption, the use of semi-elemental formula can be contemplated. To increase the caloric density of the diet, a modular lipid and/or carbohydrate supplement can be added to the formula, complementary feeding may be started earlier than usual (never before 4 months) or a hypercaloric (1kcal/mL) polymeric enteral nutrition formula for infants may be used. Generally, the total oral fluid intake should not exceed 165mL/kg/day and the sodium intake should not exceed 2.2–3 mEq/kg/day.

General nutritional support guidelines for infants with CHD.

| Type of nutrition: | Route of administration: |

|---|---|

|

|

| Other recommendations | |

|

CHD, congenital heart disease; NGT, nasogastric tube.

As for the route of administration, the oral route is recommended as the route of choice, restricting the use of nasogastric tube feeding to cases in which oral delivery worsens haemodynamic status or causes fatigue, respiratory distress or hypoxaemia, or in patients with significantly increased nutritional requirements (nutritional rehabilitation) or a high energy expenditure.

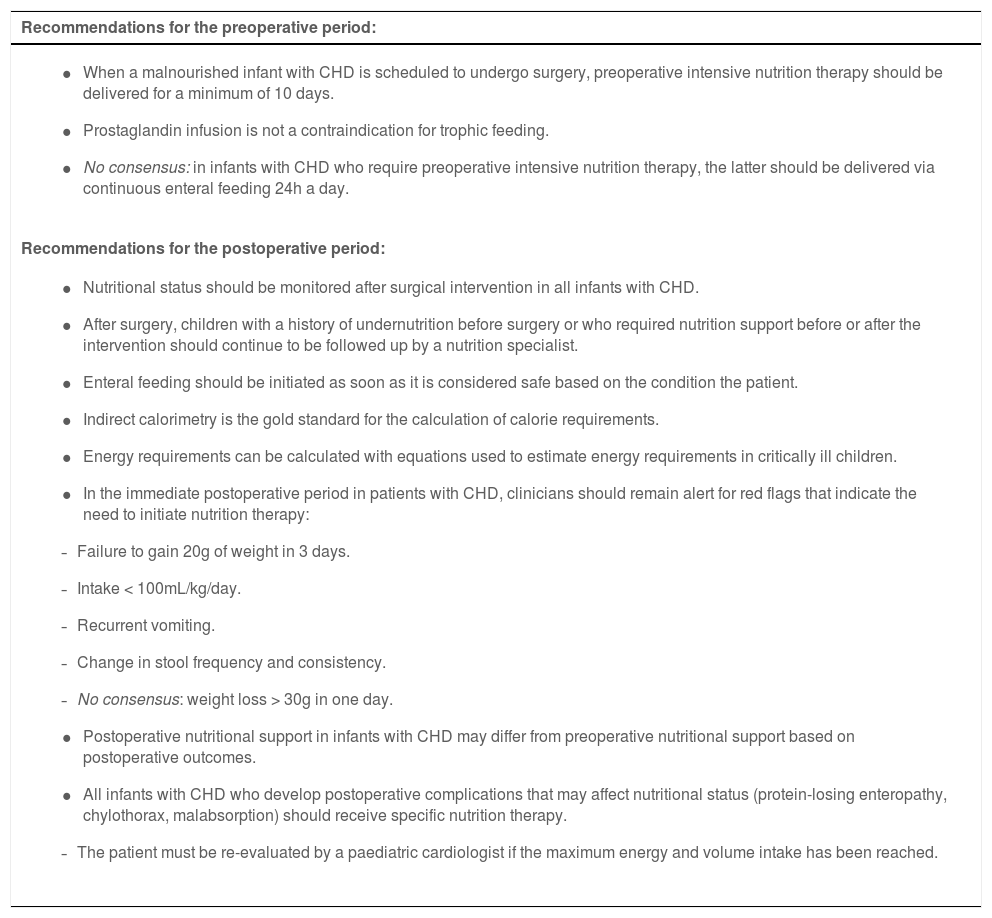

The panel also agreed on recommendations for pre- and postoperative nutritional support (Table 8). When a surgical intervention is planned in a malnourished infant with CHD, the patient should receive preoperative intensive nutritional support for a minimum of 10 days. After the intervention, children with a history of undernutrition before surgery or who required nutritional support before or after surgery should continue to be followed up by a nutritionist.

Recommendations for pre- and postoperative nutritional support of infants with CHD.

| Recommendations for the preoperative period: |

|---|

|

| Recommendations for the postoperative period: |

|

CHD, congenital heart disease.

In cases in which, despite the surgical intervention, the established nutritional targets are not met, the child should be re-evaluated by a paediatric cardiologist.

DiscussionThis consensus document offers guidelines for the referral to nutrition services, nutritional evaluation, estimation of nutritional requirements and nutritional therapy of infants with CHD. It may be a useful resource for clinicians who manage this type of patient and may have a positive impact by improving the treatment and outcomes of infants with CHD.

Concerning the identification of patients at risk, the classification of patients into high or low nutritional risk based on the type of heart disease (Table 1) may be a useful first step, especially for the paediatricians initially in charge of the infant. However, the actual nutritional risk in each case of heart disease depends on a host of associated factors.11,17,18 Therefore, other cardiac and extracardiac factors must be taken into account, in addition to other associated clinical conditions (Table 2).18,19 Generally speaking, cyanotic heart disease or CHD with pulmonary hypertension are associated with greater growth delays, whereas acyanotic heart disease is associated with greater wasting.2 The development and progression of undernutrition in these patients is largely dependent on the haemodynamic impact of the cardiac lesions, the development of heart failure, delays in surgical repair, prolonged intubation and feeding intolerance, and pulmonary hypertension is the factor most strongly associated with preoperative undernutrition.2 In this consensus process, an agreement was not reached for the classification of specific CHDs as carrying a high or low nutritional risk (Table 2). It must be taken into account that the nutritional risk associated with cor triatriatum may vary based on the degree of stenosis, the presence of additional anomalies and especially the presence of pulmonary hypertension.20,21 In the case of coarctation of the aorta, nutritional risk depends on the severity and location of the coarctation, and whether the coarctation is repaired early. In the case of partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, there are certain haemodynamically significant conditions, such as scimitar syndrome or sinus venosus atrial septal defect, which would have an impact on the degree of pulmonary hypertension and therefore nutritional risk.22,23 Thus, in addition to the specific CHD, the assessment of nutritional risk must take into account associated factors that may affect this risk.11,17,18

When it comes to the referral to the PNU (Table 3), we consider that the key message is that patients should be referred early, that is, when nutritional risk is identified, without needing to wait for the patient to lose weight or become malnourished.24

Section III proposed statements regarding the assessment to be performed at the PNU. These statements were based on the guidelines of the AEP18,25 and the SECPCC.5 With the items assessed in the consensus process, an instrument was developed that may prove useful in clinical practice (Table 4). The recommendations for the initial workup depend largely on the particular clinical picture and on the suspicion of any specific disease. For instance, measurement of immunoglobulin levels may be useful in patients who have undergone a Fontan procedure in whom protein-losing enteropathy is suspected.26 Various laboratory measurements were not considered indispensable in all infants with CHD. However, they are shown in the table because these tests may be considered in some cases.

The panel agreed that some form of assessment of body composition should be included in the evaluation of infants with infant with CHD. In addition to anthropometric measurements, there are other direct methods, such as densitometry, bioimpedance, imaging techniques, isotopic methods, etc.5 Their use will depend on the resources of each facility and the clinical features of the patient.

When it came to the classification of nutritional status, the consensus was that criteria based on percentiles or z scores and the use of indices including the weight-for-height, weight-for-age and height-for-age should be applied, in agreement with the recommendations of different guidelines.10 On the other hand, a consensus could not be reached regarding the use of national growth charts or nutritional values in healthy infants in Spain as reference in the assessment of infants with CHD (Appendix B, Table S3, item 112). In their comments, numerous panellists recommended the use of the growth standards of the World Health Organization (WHO), as recommended in the guidelines of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) or the European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) for critically ill children.9,13,27 The WHO has proposed international growth standards for weight, length/height, head circumference, arm circumference and triceps and subscapular skinfolds and calculation of the weight-for-height and the body mass index (BMI). These standards include data for breastfed children aged 0–5 years from different countries across the world. The data are presented in the form of tables or charts of percentiles or z scores.18,28 However, it is important to keep in mind that when there is an associated genetic disorder (Down syndrome, Noonan syndrome, etc.) the pattern of growth is not consistent with the growth charts and standards published to date. In these cases it is possible to use specialised growth charts, although being aware that these charts are based on descriptive studies and not reference standards.18

For the estimation of nutritional requirements, panellists reached a consensus on recommendations regarding energy and protein requirements (Table 5) consistent with those of other guidelines and consensus documents.5,19 A consensus was not reached for an item proposing that the protein intake should amount to 6%–8% of the total calorie intake. The literature suggests an optimal protein-to-energy ratio of 9%–12%.19,25 For critically ill children, the ASPEN guidelines propose a protein intake of 2–3g/kg/day and the ESPNIC guidelines a minimum protein intake of 1.5g/kg/day.9,13,27

The section devoted to evaluation included items on the need for assessment by a speech therapist (Table 6). These recommendations are based on previous consensus documents.19 All proposed recommendations were agreed on, except for the one that contemplated referral to the speech therapist if the infant exhibited signs of discomfort or unease during or after feeding. Some panellists considered that these symptoms were not specific enough and that other possible causes, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux, should be ruled out before referring the patient.29

Lastly, the panel agreed on general recommendations for the delivery of nutritional support, its route of administration (Table 7) and nutrition in the perioperative period (Table 8) in line with previous recommendations.5,25

With regard to surgery, we ought to highlight the item that contemplates that when surgical intervention is planned in infants with CHD and malnutrition, the infant must receive intensive nutrition therapy for a minimum of 10 days before surgery (Appendix B, Table S4.3). Nearly one third of infants with CHD require some form of surgical intervention, usually in the first year of life and increasingly frequently in the neonatal period.7 Early repair decreases the probability of undernutrition, but up to 50% of children may have protein-energy undernutrition at the time of the intervention.5 In addition, a poor nutritional status in the preoperative period may be associated with unfavourable postoperative outcomes, increasing the risk of nosocomial infection and poor wound healing.7,30 Consequently, early diagnosis and adequate pre-and postoperative intervention are essential in this context.7

This work has the limitations intrinsic to the Delphi method, including the impossibility of discussing recommendations in depth or the possibility of bias in the selection of panellists. However, the scientific committee took into account the comments made by the panellists in the writing of the Discussion section and the selection of participants was very careful and included only physicians with demonstrated expertise on the subject.

In summary, infants with CHD, especially those with haemodynamically significant disease, may be at risk of undernutrition, which is associated with an increased morbidity and mortality. Thorough assessment and appropriate nutritional support of these children is crucial to improve treatment, long-term outcomes and quality of life. The committee developed consensus-based recommendations on the nutritional management of infants with CHD with the participation of physicians in all the specialities involved in their management. These recommendations could facilitate early detection and referral of patients at risk and guide the assessment, rapid estimation of nutritional requirements and appropriate nutrition and feeding of children with CHD in PNUs.

FundingThe study received funding from Danone Nutricia to support in-person and online meetings of experts.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank all panel members for their collaboration with the study.

Experts on paediatric cardiology: Sergio Flores Villar, Bárbara Fernández Barrio, María Ángeles Pérez-Moneo Agapito, Paula de Vera McMullan, Natalia Fernández Suárez, Ignacio Oulego Erroz, Beatriz Salamanca Zarzuela, Leticia Albert de la Torre, Marta Flores Fernández, María Dolores Herrera Linde, Gonzalo Cortázar Rocandio, Marta Yagüe Martín, Elena Gómez Guzmán, María Teresa Viadero Ubierna, María Isabel Martínez Soto, Olga Carvajal, Carlos Labrandero de Lera.

Experts on paediatric nutrition: Rafael Galera Martínez, Mercedes Murray Hurtado, Marta Germán Díaz, Verónica Luque, María del Carmen Rivero de la Rosa, David Gil, José Manuel MorenoVillares, Raquel Núñez, Justo Valverde Fernández, José Carlos Salazar, Elvira Cañedo, Alfonso Solar Boga, Juan José Díaz Martín, Elena Crehúa, Vanessa Cabello Ruiz.

We thank Dr Pablo Rivas for his help in providing editorial support to the project on behalf of Nueva Investigación - SPAIN.