Update of the consensus on acute otitis media (AOM) (2012) and sinusitis (2013) following the introduction of pneumococcal vaccines in the immunization schedule, and related changes, such as epidemiological variation, colonization by of nonvaccine serotypes and emerging antimicrobial resistances. A majority of studies show that the introduction of the pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine has been followed by a reduction in the nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococcus, with an increase in the proportion of drug-resistant nonvaccine serotypes. The diagnosis of AOM is still clinical, although more stringent criteria are proposed, which are based on the visualization of abnormalities in the tympanic membrane and the findings of pneumatic otoscopy performed by trained clinicians. The routine diagnosis of sinusitis is also clinical, and the use of imaging is restricted to the assessment of complications. Analgesia with acetaminophen or ibuprofen is the cornerstone of AOM management; watchful waiting or delayed antibiotic prescription may be suitable strategies in select patients. The first-line antibiotic drug in children with AOM and sinusitis and moderate to severe disease is still high-dose amoxicillin, or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in select cases. Short-course regimens lasting 5–7 days are recommended for patients with uncomplicated disease, no risk factors and a mild presentation. In allergic patients, the selection of the antibiotic agent must be individualized based on severity and whether or not the allergy is IgE-mediated. In recurrent AOM, the choice between watchful waiting, antibiotic prophylaxis or surgery must be individualized based on the clinical characteristics of the patient.

Actualización de los documentos de consenso de OMA (2012) y sinusitis (2013) tras la introducción de vacunas antineumocócicas en calendario vacunal, tras los cambios derivados de las variaciones epidemiológicas, colonización por serotipos no vacunales y la aparición de resistencias. Según la mayoría de los estudios, la introducción de la vacuna antineumocócica conjugada tridecavalente (VNC-13) se ha traducido en un descenso de la colonización nasofaríngea por neumococo, con un aumento porcentual de serotipos resistentes no cubiertos. El diagnóstico de OMA continúa siendo clínico, aunque se proponen criterios más rigurosos, apoyados en la visualización de alteraciones en la membrana timpánica y la otoscopia neumática realizada por personal entrenado. El diagnóstico rutinario de la sinusitis es clínico y la realización de pruebas de imagen está limitada al diagnóstico de complicaciones asociadas. La analgesia con paracetamol o ibuprofeno es la base del tratamiento en la OMA; la conducta expectante o la prescripción antibiótica diferida podrían ser estrategias adecuadas en pacientes seleccionados. El tratamiento antibiótico de elección en niños con OMA y sinusitis aguda con síntomas moderados-graves continúa siendo amoxicilina a dosis altas, o amoxicilina-clavulánico en casos seleccionados. En cuadros no complicados, sin factores de riesgo y con buena evolución se proponen pautas cortas de 5–7 días. En pacientes alérgicos se debe individualizar especialmente la indicación de tratamiento antibiótico, que dependerá del estado clínico y si existe o no alergia IgE-mediada. En OMA recurrente, la elección entre un manejo expectante, profilaxis antibiótica o cirugía se debe individualizar según las características del paciente.

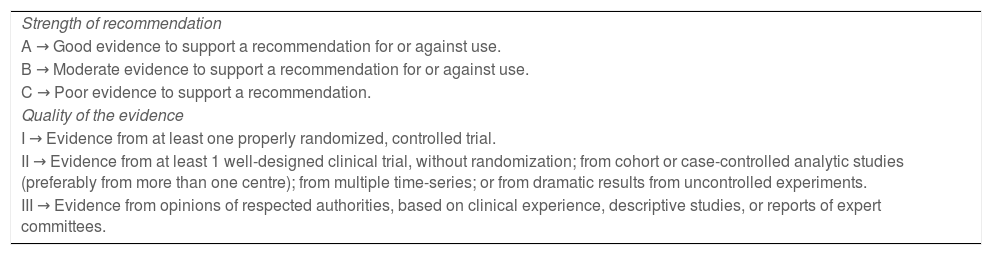

In 2012 and 2013, the Working Group on Infectious with Outpatient Management of the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP) published its consensus document on the aetiology, diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media1 and its consensus document on the aetiology, diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis,2 respectively, in collaboration with the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics), the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPap, Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics), the Sociedad Española De Pediatría Extrahospitalaria Y Atención Primaria (SEPEAP, Spanish Society of Outpatient and Primary Care Paediatrics), the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría (SEUP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine) and the Sociedad Española de Otorrinolaringología y Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello (SEORL-CCC, Spanish Society of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery). Due to the epidemiological changes that have taken place following the introduction of routine vaccination against pneumococcal disease, it seemed relevant to update these documents. A joint approach to both diseases appeared preferable, given the overlap in their causative agents, by presenting 11 questions and answers on the most important aspects that may have changed since. A new group of experts was established with representation of the same societies. After performing a specific literature review, the details of which are presented in Appendix B, the group has expressed its results in the form of recommendations. The quality of the evidence and strength of recommendations were assessed with the grading system of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the United States Public Health Service for clinical practice guidelines (Table 1). Each recommendation was submitted to voting by all members of the group to reach a consensus.

Evidence grading classification of the Infectious Disease Society of America and the US Public Health Service for recommendations in clinical practice guidelines.

| Strength of recommendation |

| A → Good evidence to support a recommendation for or against use. |

| B → Moderate evidence to support a recommendation for or against use. |

| C → Poor evidence to support a recommendation. |

| Quality of the evidence |

| I → Evidence from at least one properly randomized, controlled trial. |

| II → Evidence from at least 1 well-designed clinical trial, without randomization; from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies (preferably from more than one centre); from multiple time-series; or from dramatic results from uncontrolled experiments. |

| III → Evidence from opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees. |

There was ample heterogeneity in the consulted literature, as vaccines and vaccine coverages, microbiological tests, diagnostic criteria, clinical forms and recommended treatments varied based on the countries where studies were conducted. Still, most authors agreed on three points regarding vaccination with PCV-133–8:

- 1

The vaccine has had a larger than expected impact in the prevention of AOM and the decrease in the prevalence of nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine serotypes, with the exception of 19A (a smaller reduction in the number of cases).

- 2

It has resulted in shifts in the aetiology of both diseases. At present, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the predominant causative agents of AOM in healthy children, with frequency distributions that vary between studies. In many studies, NTHi was the leading cause of AOM. In the case of pneumococcus, there has also been an increase in the proportion of cases caused by nonvaccine serotypes. Moraxella catarrhalis continues to be the third most frequent causative agent, with an increased proportion of cases caused by this agent compared to the pre-vaccine period (partly explained by molecular detection techniques).

- 3

There has not been a significant decrease in the relative frequency of penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which remains at 15%–30% depending on the publication, on account of the emergence of nonvaccine serotypes. In Spain, most of these strains belong to serotypes 23B, 24F, 14 and 11A, associated with clonal complex 156.

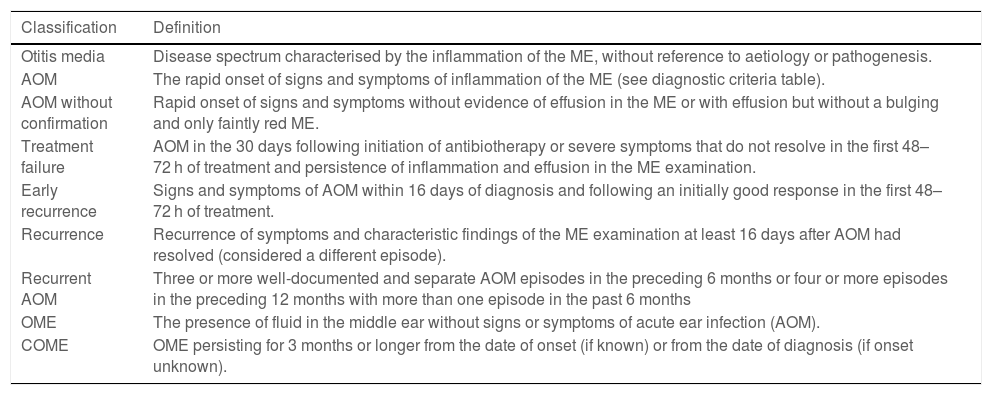

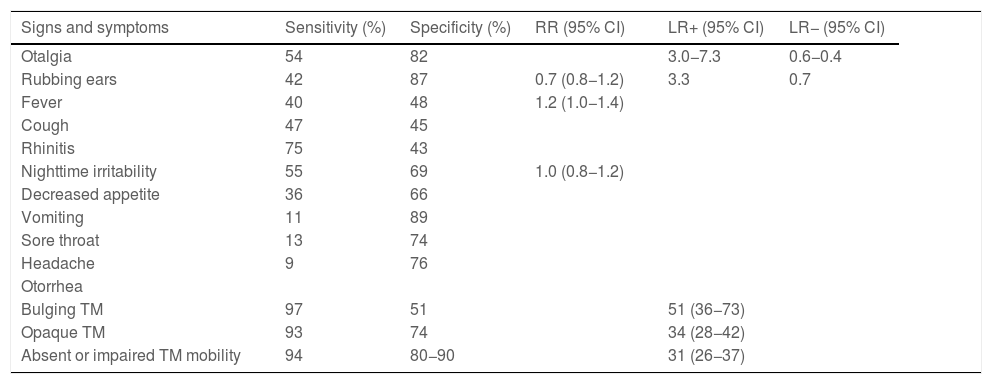

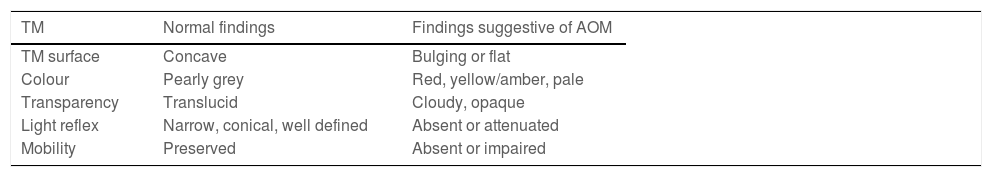

Acute otitis media belongs to a spectrum of diseases that involve the middle ear (ME) and with different definitions (Table 2).9,10 The diagnosis is usually based on the clinical presentation, as the routine use of the gold standard (tympanocentesis) would not be justified. The specificity of symptoms decreases the younger the patient (Table 3),11 and changes in the tympanic membrane (TM) are difficult to distinguish and interpret in some cases (Table 4).12,13 Recent systematic reviews and clinical guidelines recommend the application of more precise diagnostic criteria (Table 5) and consider the examination of the TM indispensable.9,11,12 Bulging evinces the presence of exudate, especially if the TM is opacified and its mobility impaired, and it is considered the most characteristic finding of bacterial AOM.12 The concepts of “uncertain” or “probable” diagnosis should be avoided, and repetition of the examination in 48 h is a preferred approach.10,13 The severity is established based on the characteristics of the patient and the clinical presentation (Table 6).9

Definition of the inflammatory diseases of the middle ear.

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Otitis media | Disease spectrum characterised by the inflammation of the ME, without reference to aetiology or pathogenesis. |

| AOM | The rapid onset of signs and symptoms of inflammation of the ME (see diagnostic criteria table). |

| AOM without confirmation | Rapid onset of signs and symptoms without evidence of effusion in the ME or with effusion but without a bulging and only faintly red ME. |

| Treatment failure | AOM in the 30 days following initiation of antibiotherapy or severe symptoms that do not resolve in the first 48–72 h of treatment and persistence of inflammation and effusion in the ME examination. |

| Early recurrence | Signs and symptoms of AOM within 16 days of diagnosis and following an initially good response in the first 48–72 h of treatment. |

| Recurrence | Recurrence of symptoms and characteristic findings of the ME examination at least 16 days after AOM had resolved (considered a different episode). |

| Recurrent AOM | Three or more well-documented and separate AOM episodes in the preceding 6 months or four or more episodes in the preceding 12 months with more than one episode in the past 6 months |

| OME | The presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of acute ear infection (AOM). |

| COME | OME persisting for 3 months or longer from the date of onset (if known) or from the date of diagnosis (if onset unknown). |

Sensitivity and specificity of the signs and symptoms associated with otitis.

| Signs and symptoms | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | RR (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otalgia | 54 | 82 | 3.0−7.3 | 0.6−0.4 | |

| Rubbing ears | 42 | 87 | 0.7 (0.8−1.2) | 3.3 | 0.7 |

| Fever | 40 | 48 | 1.2 (1.0−1.4) | ||

| Cough | 47 | 45 | |||

| Rhinitis | 75 | 43 | |||

| Nighttime irritability | 55 | 69 | 1.0 (0.8−1.2) | ||

| Decreased appetite | 36 | 66 | |||

| Vomiting | 11 | 89 | |||

| Sore throat | 13 | 74 | |||

| Headache | 9 | 76 | |||

| Otorrhea | |||||

| Bulging TM | 97 | 51 | 51 (36−73) | ||

| Opaque TM | 93 | 74 | 34 (28−42) | ||

| Absent or impaired TM mobility | 94 | 80−90 | 31 (26−37) |

Ear pain, fever, food refusal, restless sleep and irritability combined: statistically significant prediction of AOM (P = .006), with a very low sensitivity.

AOM, acute otitis media; CI, confidence interval; LR, likelihood ratio; RR, relative risk; TM, tympanic membrane.

Source: Suzuki et al.11 (adapted from Routhman R, Owens T, Simel DL. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA 2003;290:1633-1640).

Normal and pathological otoscopy findings.

| TM | Normal findings | Findings suggestive of AOM |

|---|---|---|

| TM surface | Concave | Bulging or flat |

| Colour | Pearly grey | Red, yellow/amber, pale |

| Transparency | Translucid | Cloudy, opaque |

| Light reflex | Narrow, conical, well defined | Absent or attenuated |

| Mobility | Preserved | Absent or impaired |

AOM, acute otitis media; TM, tympanic membrane.

Source: Gaddey et al.12

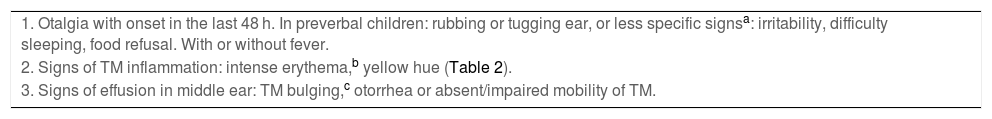

Diagnostic criteria for confirmed AOM.

| 1. Otalgia with onset in the last 48 h. In preverbal children: rubbing or tugging ear, or less specific signsa: irritability, difficulty sleeping, food refusal. With or without fever. |

| 2. Signs of TM inflammation: intense erythema,b yellow hue (Table 2). |

| 3. Signs of effusion in middle ear: TM bulging,c otorrhea or absent/impaired mobility of TM. |

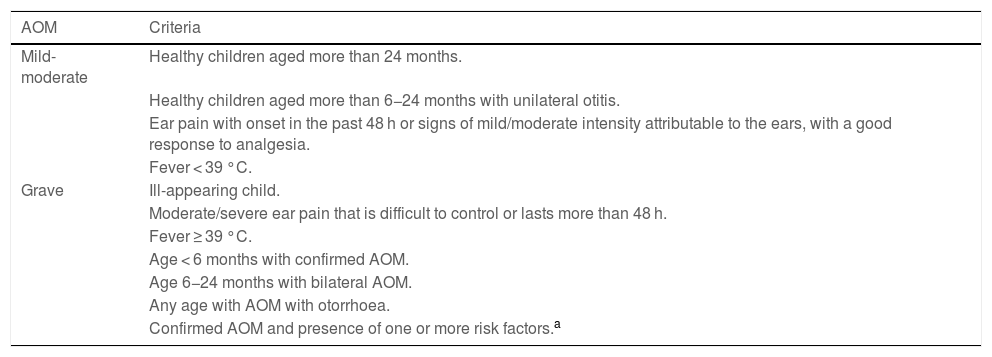

Classification of AOM severity.

| AOM | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Mild-moderate | Healthy children aged more than 24 months. |

| Healthy children aged more than 6−24 months with unilateral otitis. | |

| Ear pain with onset in the past 48 h or signs of mild/moderate intensity attributable to the ears, with a good response to analgesia. | |

| Fever < 39 °C. | |

| Grave | Ill-appearing child. |

| Moderate/severe ear pain that is difficult to control or lasts more than 48 h. | |

| Fever ≥ 39 °C. | |

| Age < 6 months with confirmed AOM. | |

| Age 6−24 months with bilateral AOM. | |

| Any age with AOM with otorrhoea. | |

| Confirmed AOM and presence of one or more risk factors.a |

In every case, signs of inflammation of the TM and signs of effusion in the middle ear are both required for diagnosis.

AOM, acute otitis media; TM, tympanic membrane.

Source: Schilder et al.9

Pneumatic otoscopy can evince impairment or near absence of mobility in the eardrum due to space occupation, which occurs both in AOM and in otitis media with effusion (OME).14,15 In some cases, these 2 entities may be considered different stages of the same disease, which is classified as AOM if it presents with manifestations of acute infection, and has implications for clinical care.16

As of 2013, the American Academy of Pediatrics assigned the evidence in support of the recommendation to use pneumatic otoscopy a grade B quality, although there were expert clinicians that did not consider it necessary, and there is evidence of a lower sensitivity and specificity when performed by inexperienced examiners.16,17 In 2018, the international consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children published by Simon et al. recommended the use of pneumatic otoscopy in the diagnosis of OME (grade A evidence).18 The 2022 update of the clinical practice guideline on tympanostomy tubes in children published by Rosenfeld et al. states that pneumatic otoscopy is the method of choice when there are doubts regarding the presence of effusion in the middle ear.19

Have there been any changes in the diagnosis of sinusitis?The diagnosis of sinusitis is still based on the clinical presentation; the features suggestive of a bacterial aetiology are cough and nasal discharge lasting longer than 10 days in the context of upper respiratory tract infection, fever greater than 39 °C and purulent nasal discharge lasting 3–4 days.

Sinus puncture and aspiration is the only method that allows certain aetiological diagnosis, but its use is only indicated in select cases; it should be contemplated carefully in patients with septic appearance, intracranial complications, immunosuppression, recurrent sinusitis or who do not respond to the customary antibiotic treatment.20 Although some authors propose culture of middle meatal fluid specimens obtained by endoscopy as an alternative to sinus puncture and aspiration, this procedure is not useful in the paediatric age group because the meatus is usually colonised by pathogenic bacteria even in asymptomatic children.20

Nasopharyngeal samples are not an adequate alternative either: there is no correlation with the results obtained in sinus aspiration samples, and negative results in nasopharyngeal samples do not rule out the presence of sinusitis.21

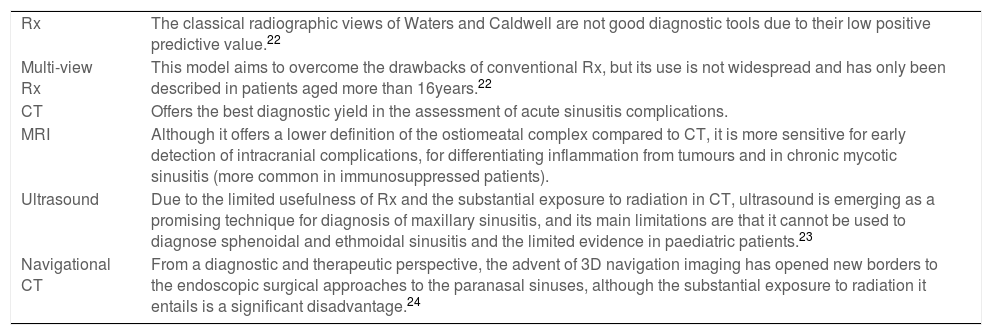

At present, the sole indication for imaging tests in patients with sinusitis is the suspicion of complications. Table 7 summarises the characteristics of the different imaging tests along with their advantages and disadvantages, and the recommendations regarding their use can be found at the end of this text.22,24

Imaging tests in the diagnosis of sinusitis.

| Rx | The classical radiographic views of Waters and Caldwell are not good diagnostic tools due to their low positive predictive value.22 |

| Multi-view Rx | This model aims to overcome the drawbacks of conventional Rx, but its use is not widespread and has only been described in patients aged more than 16years.22 |

| CT | Offers the best diagnostic yield in the assessment of acute sinusitis complications. |

| MRI | Although it offers a lower definition of the ostiomeatal complex compared to CT, it is more sensitive for early detection of intracranial complications, for differentiating inflammation from tumours and in chronic mycotic sinusitis (more common in immunosuppressed patients). |

| Ultrasound | Due to the limited usefulness of Rx and the substantial exposure to radiation in CT, ultrasound is emerging as a promising technique for diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis, and its main limitations are that it cannot be used to diagnose sphenoidal and ethmoidal sinusitis and the limited evidence in paediatric patients.23 |

| Navigational CT | From a diagnostic and therapeutic perspective, the advent of 3D navigation imaging has opened new borders to the endoscopic surgical approaches to the paranasal sinuses, although the substantial exposure to radiation it entails is a significant disadvantage.24 |

Pain is the main symptom of AOM and ineffective pain management is associated with an increase in antibiotic consumption, repeat visits and failure of the watchful waiting approach.25 The management of AOM should always include appropriate analgesia, and the agent of choice is paracetamol or ibuprofen, administered orally at doses and intervals appropriate for the patient’s age and weight.26 There is no evidence of any difference in efficacy or adverse events between these two drugs, and alternating the two is not recommended based on the Cochrane systematic review published in 2016.27

Myringotomy, historically considered a treatment option for poorly controlled pain, does not play this role now. In addition to its technical difficulty and the risks it carries, it has been demonstrated to be less effective in alleviating pain than oral analgesia.26

In recent years, evidence has emerged on the potential benefits of topical anaesthetics (ear drops): systematic reviews have provided limited evidence on their use, and they are contraindicated in the case of eardrum perforation.28 One of the aspects that supports their use is that it may increase the success of delayed prescribing strategies, thus reducing the use of antibiotics and their systemic effects.29

Could watchful waiting/wait and see or delayed antibiotic prescribing as the initial approach optimise the management of acute otitis media?Approximately 80% of cases of AOM resolve spontaneously. For this reason, immediate antibiotic prescribing would only be indicated in the following cases: age less than 6 months, otorrhoea, bilateral AOM, severe unilateral AOM (Table 6), immunosuppression or circumstances precluding adequate followup.1,30,31

In recent years, a growing number of publications have addressed delayed prescribing in the management of uncomplicated respiratory infections in children. They usually compare 3 groups of patients in relation to the use of antibiotics: immediate prescribing, delayed prescribing and no prescribing.32–34

In children aged more than 6 months in good general health presenting with ear pain, the literature supports prescription of analgesia and delaying initiation of antibiotherapy for 48–72 h with adequate outpatient followup (watchful waiting) as long as the onset of ear occurred in the past 48 h.16,34 In children aged 6–24 months, this “wait and see” approach has been found to fail more frequently on account of a longer duration of symptoms, with increased health care costs and time off work in families, although without an increased risk of complications.33,34

The delayed prescribing strategy can be contemplated in children aged more than 6 months, without severe or bilateral AOM and without otorrhoea, after educating the family about warning signs, offering to initiate antibiotherapy if they detect worsening of symptoms despite analgesia (thus, this strategy depends on the reliability and vigilance of caregivers). This strategy has been found to reduce antibiotic consumption by up to 30%–50% in studies conducted in Spain, without an associated increase in the duration of symptoms or the incidence of complications.32

Could watchful waiting or delayed antibiotic prescribing be also used for the management of sinusitis in children?Acute sinusitis resolves spontaneously in 60%–80% of cases.2 The consensus document published in 2013 recommended restricting the initiation of antibiotherapy to select cases (persistence of symptoms or evident clinical worsening).2 The guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics propose the same criteria, adding the possibility of watchful waiting even in the case of upper respiratory symptoms of more than 10 days’ duration, with the consent of the family or caregivers and excluding patients with underlying disease.33

Some studies have found no differences in the frequency of resolution or the development of complications independently of the clinical severity at diagnosis,32 while others have found some differences.33 In any case, the delayed prescribing and no prescribing strategies always require close clinical monitoring of the patient to watch for the development of potential complications.34

Which is the first-line antibiotic agent for acute otitis media and sinusitis after the introduction of routine vaccination with PCV-13?In European AOM guidelines, 82% of countries recommend amoxicillin as the first-line agent for empiric antibiotherapy, of which 50% recommend high-dose antibiotherapy (80−90 mg/kg/day given in 2 or 3 doses up to a maximum of 3 g/day).10,31 Due to the emergence of nonvaccine serotypes with decreased susceptibility to penicillin documented in studies conducted after the introduction of the PCV-13, prescription of the standard dose is an alternative not currently recommended.35–37 If the presentation is severe, there are risk factors or infection by H influenzae is suspected (age < 6 months, incomplete vaccination, association with purulent conjunctivitis, recurrence, antibiotherapy in the past 30 days), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid should be prescribed at a 8:1 ratio (dosage: 80−90 mg amoxicillin/kg/day given in 2 or 3 doses).1,38 The use of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid outside of these exceptional cases has not been associated with an increase in adverse events, complications or treatment failure.39

Are short courses of antibiotherapy safe for treatment of acute otitis media and sinusitis?Recent studies demonstrate that the use of short courses of antibiotherapy is not associated with an increased frequency of treatment failure or complications in the management of paediatric infections at the outpatient level while it is associated with a decreased incidence of adverse events.40,41 A clinical trial conducted by Hoberman et al. (2016) compared courses of 5 vs 10 days of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in patients aged 6–23 months, concluding that the shortened course was associated with a higher frequency of clinical failure. However, clinical failure rates were higher in patients with greater exposure to the pathogen, more severe disease and less favourable characteristics at onset independently of the treatment group they were allocated to, which suggests that clinical failure was more strongly associated with individual factors.42 A study on the implementation of clinical practice guidelines conducted in Italy in 2019 (ProBA project) found that the 5-day course of antibiotherapy for treatment of AOM was not associated with an increased incidence of mastoiditis, but was associated with a reduction in antibiotic use and adverse events.43 As concerns acute sinusitis, a meta-analysis published in 2009 did not find evidence of increased complications in patients with acute uncomplicated sinusitis treated with a short course (5–6 days) versus standard course (10 days) of antibiotherapy44; although at the time of this writing, there is no evidence on the subject from clinical trials.

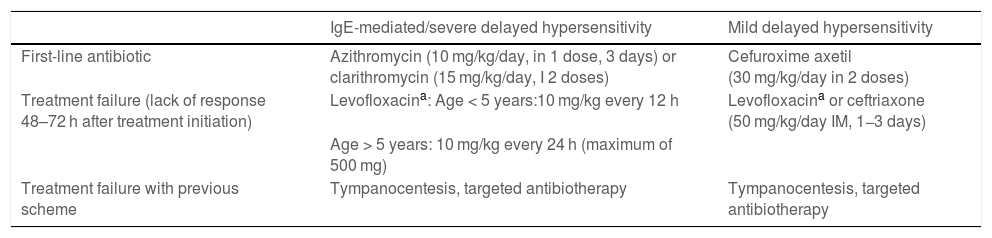

Which are the alternative antibiotic agents to use for treatment of acute otitis media and sinusitis in patients allergic to first-line treatment?In patients allergic to amoxicillin, the alternative antibiotic agent should match to the extent possible the efficacy and spectrum of the first-line drug. Table 8 presents the available alternatives, which should also be selected based on the type of hypersensitivity reaction (IgE-mediated or not) and its severity.16,45,46 In the case of non-IgE-mediated reactions, if the allergy is not due to the β-lactam ring, consider treatment with a cephalosporin with a different R side chain to those present in aminopenicillins: the drug of choice would be cefuroxime axetil (avoiding cefadroxil and cefaclor) and, should it fail, ceftriaxone administered intramuscularly. The selection and administration will take place under the supervision of the department of allergy, as long as the skin allergy tests are negative, and with close monitoring of the patient. The risk of cross-reactivity is estimated at approximately 0.1%–0.5%.16,46

Treatment of AOM and sinusitis in patients allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics.

| IgE-mediated/severe delayed hypersensitivity | Mild delayed hypersensitivity | |

|---|---|---|

| First-line antibiotic | Azithromycin (10 mg/kg/day, in 1 dose, 3 days) or clarithromycin (15 mg/kg/day, I 2 doses) | Cefuroxime axetil (30 mg/kg/day in 2 doses) |

| Treatment failure (lack of response 48–72 h after treatment initiation) | Levofloxacina: Age < 5 years:10 mg/kg every 12 h | Levofloxacina or ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/day IM, 1−3 days) |

| Age > 5 years: 10 mg/kg every 24 h (maximum of 500 mg) | ||

| Treatment failure with previous scheme | Tympanocentesis, targeted antibiotherapy | Tympanocentesis, targeted antibiotherapy |

The most frequently used preventive strategies are watchful waiting, antibiotic prophylaxis and surgery. Other evidence-based measures routinely recommended are breastfeeding, avoidance of tobacco smoke, avoidance of pacifiers/binkies in infants aged more than 6 months, health education regarding the risks of early attendance to nurseries, vaccination against pneumococcal and annual vaccination against seasonal influenza. There is not sufficient evidence to recommend supplementation with probiotics, oligosaccharides, xylitol or vitamin D.47

- 1

Watchful waiting/wait and see: close observation or antibiotic treatment in each episode of AOM. This strategy is particularly recommended in children aged more than 2 years, on account of the decreased frequency of AOM episodes due to the maturity of the immune system and anatomical changes in the Eustachian tube.

- 2

Antibiotic prophylaxis: it can reduce the frequency of episodes, although the protective effect does not endure after it is discontinued and it can cause diarrhoea, allergic reactions and selective pressure contributing to antimicrobial resistance.48 It must be reserve for very select cases, chiefly children aged less than 2 years with anaesthetic/surgical risk, predisposing anatomical features, immunosuppression or carrying hearing aids.21 The most frequently used drug is amoxicillin, given in a single dose of 20 mg/kg/day, although a dose of up to 40 mg/kg/day may be used in areas with a high prevalence of resistant pneumococcus. In Spain, routine prophylaxis with macrolides or cotrimoxazole is not appropriate given the resistance of pneumococcus to these antibiotics. Prophylaxis has to be administered daily, especially in winter, preferably for periods not exceeding 6 months.

- 3

Surgery: it is the standard of care if prophylaxis fails or is refused, in patients allergic to amoxicillin or in the case of persistent OME (especially if it is associated with a functional impairment in language or progressive hearing loss).47,49,50 The usual approach is myringotomy and placement of a tympanostomy tube (TT). There is no clear evidence that this intervention achieves a reduction in the number of episodes of recurrent AOM, although it does prolong the time elapsed to the first recurrence and achieves a reduction in the use of antibiotics (decreased severity and duration of episodes); otorrhoea frequently develops after surgery, although it is possible to use topical antibiotherapy in the form of eardrops. The drawbacks of TTs include the possibility of permanent perforation of the tympanic membrane, tympanosclerosis, focal atrophy and cholesteatoma.47 Adenoidectomy, with or without tonsillectomy, does not seem to be effective in preventing recurrent AOM, and should only be considered at the outset if there are symptoms directly related to adenoid enlargement or when the TT needs to be reinserted due to new episodes of recurrent AOM in children aged more than 2 years (some studies have found evidence suggestive of a decrease in the frequency of hospital admission and TT reinsertion).19,47

The conclusions drawn from the review of the questions discussed earlier in the text and the recommendations of the working group on the most relevant clinical aspects are presented below. The quality of the evidence in support of the recommendation, the strength of recommendation and the results of the voting of the consensus group for each of them can be found in Appendix C:

- •

The diagnosis of AOM calls for more rigorous clinical criteria and should be based on the visualization of changes in the tympanic membrane.

- •

Avoid terms such as “uncertain” or “probable” diagnosis, and instead make a new assessment in 48 h whenever possible based on the characteristics of the patient.

- •

Consider pneumatic otoscopy performed by an experienced examiner as a useful diagnostic test for assessment of exudate in the middle ear.

- •

The routine diagnosis of sinusitis is clinical, and aetiological diagnosis (performance of sinus puncture and aspiration) is only indicated in select cases.

- •

Computed tomography is the imaging technique of choice for diagnosis of sinusitis complications, in addition to MRI in very select cases.

- •

Ultrasound is promising in the case of maxillary sinusitis, although there is limited evidence of its use in paediatric patients.

- •

Analgesia with paracetamol or ibuprofen at appropriate doses is the cornerstone of treatment of AOM.

- •

Myringotomy is not recommended for routine treatment of AOM.

- •

Topical anaesthetic drops should not be used routinely in the management of AOM.

- •

Watchful waiting or delayed antibiotic prescribing, after educating caregivers appropriately, could be adequate strategies for the management of AOM in children aged more than 6 months if there are no risk factors.

- •

Clinical criteria should be applied to select patients with sinusitis that could benefit from antibiotherapy and to individualize treatment.

- •

In the management of sinusitis, delayed prescribing and watchful waiting require close clinical monitoring to watch for the development of complications.

- •

The antibiotic agent of choice for AOM and sinusitis in children with moderate symptoms and no risk factors continues to be amoxicillin at 80−90 mg/kg/day given in 3 doses.

- •

If there is evidence of severity, risk factors or suspicion of infection by H influenzae (age < 6 months, incomplete vaccination, association with purulent conjunctivitis, recurrence, antibiotherapy in the past 30 days): use amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at an 8:1 ratio (dosage: 80−90 mg amoxicillin/kg/day in 2 or 3 doses).

- •

For paediatric patients aged more than 2 years with AOM and uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis with a favourable initial clinical course and without risk factors, a short course of 5 days is recommended, and in children aged less than 2 years, courses of 7–10 days.

- •

The duration of antibiotherapy should be individualised (especially in patients with an insidious course or at risk of complications), always taking into account the response to treatment.

- •

The individualization of antibiotherapy is particularly important in patients allergic to amoxicillin and should be based in the results of culture whenever collection of a sample is indicated.

- •

The presence or absence of IgE-mediated allergy to amoxicillin, the severity of the allergy and the clinical course should guide therapeutic decision-making.

- •

The first step in the management of recurrent AOM should be the detection of predisposing factors, promoting protective factors and avoiding risk behaviours.

- •

The approach to the management of recurrent AOM should be individualised based on the characteristics of the patient: surgery in children aged less than 2 years in whom the disease is causing functional impairment in language or hearing and persistent OME, antibiotic prophylaxis in children aged less than 2 years in whom the disease is causing functional impairment in language or hearing and with high surgical risk and watchful waiting in children aged more than 2 years.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Reviewers:

Santiago Alfayate Miguélez; IMIB. Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP).

Cándida B Cabral Soares; Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid. Sociedad Española de Otorinolaringología y Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello (SEORL-CCC).

Cristina Calvo; Department of Paediatrics and Infectious Diseases, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Fundación Idipaz. CIBERINFEC ISCIII. Red de Investigación traslacional en Infectología Pediátrica, Madrid. Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP).

María J Cilleruelo Ortega; Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría. Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP).

Josep de la Flor i Brú; El Serral Sant Vicenç dels Horts Primary Care Centre, Institut Català de la Salut, Barcelona. Sociedad Española de Pediatría Extrahospitalaria y Atención Primaria (SEPEAP).

Ana M Llorens Córcoles; Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid. Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría (SEUP).

Olga Ramírez Balza; Asociación Española de Atención Primaria (AEPap). Group on Infectious Diseases of the AEPap. Centro de Salud Collado Villalba, Madrid.

Marta Cruz Cañete; Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP), Department of Paediatrics. Hospital de Montilla, Cordoba.

- •

The consensus document was developed starting from a list of research questions agreed on by a work group comprised of paediatricians and otorhinolaryngologists affiliated to various scientific societies (AEP, SEIP, AEPAP, SEPEAP, SEUP and SEORL-CCC).

- •

A literature search in PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase and CINAHL, breaking down the evidence available to answer each question.

- •

The keywords used in the search for sources in English were Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: acute otitis media, sinusitis, consensus, guidelines; the keywords used to search for sources in Spanish were terms included in the Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud (DeCS) controlled multilingual vocabulary: consenso, otitis media aguda, sinusitis, guía de práctica clínica.

- •

Selection of sources published in the past 10 years, prioritising those published in the past 5 years, without exclusion of older sources if they were cited frequently. Sources were also sought in the reference section of the articles identified with the search strategy just described. The sources included websites and book chapters because they provided general descriptions of the subject of interest.

- •

An age filter of 0–18 years was applied to the search.

- •

The diagnosis of AOM calls for more rigorous clinical criteria and should be based on the visualization of changes in the tympanic membrane. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

Avoid terms such as “uncertain” or “probable” diagnosis, and instead make a new assessment in 48 h whenever possible based on the characteristics of the patient. Quality of evidence: III. Strength of recommendation: C. Vote: 17 in agreement, 1 abstained (SAM, IJH), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 88%.

- •

Consider pneumatic otoscopy performed by an experienced examiner as a useful diagnostic test for assessment of exudate in the middle ear. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 15 in agreement, 2 abstained (PKP, MCC), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 88%.

- •

The routine diagnosis of sinusitis is clinical, and aetiological diagnosis (performance of sinus puncture and aspiration) is only indicated in select cases. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

Computed tomography is the imaging technique of choice for diagnosis of sinusitis complications, in addition to MRI in very select cases. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: B. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

Ultrasound is promising in the case of maxillary sinusitis, although there is limited evidence of its use in paediatric patients. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: C. Vote: 16 in agreement, 2 abstained (JAA, SAM), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 88%.

- •

Analgesia with paracetamol or ibuprofen at appropriate doses is the cornerstone of treatment of AOM. Quality of evidence: I. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 16 in agreement, 1 abstained (CC), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 94%.

- •

Myringotomy is not recommended for routine treatment of AOM. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: B. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

Topical anaesthetic drops should not be used routinely in the management of AOM. Quality of evidence: III. Strength of recommendation: C. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

Watchful waiting or delayed antibiotic prescribing, after educating caregivers appropriately, could be adequate strategies for the management of AOM in children aged more than 6 months if there are no risk factors. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 14 in agreement, 1 abstained (TCC), 1 in disagreement (JFB, PKP). Level of consensus: 82%.

- •

Clinical criteria should be applied to select patients with sinusitis that could benefit from antibiotherapy and to individualize treatment. Quality of evidence: I. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 16 in agreement, 0 abstained, 1 in disagreement (PKP). Level of consensus: 94%.

- •

In the management of sinusitis, delayed prescribing and watchful waiting require close clinical monitoring to watch for the development of complications. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

The antibiotic agent of choice for AOM and sinusitis in children with moderate symptoms and no risk factors continues to be amoxicillin at 80−90 mg/kg/day in 3 doses. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

If there is evidence of severity, risk factors or suspicion of infection by H influenzae (age < 6 months, incomplete vaccination, association with purulent conjunctivitis, recurrence, antibiotherapy in the past 30 days): use amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at an 8:1 ratio (dosage: 80−90 mg amoxicillin/kg/day in 2 or 3 doses). Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

For paediatric patients aged more than 2 years with AOM and uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis with a favourable initial clinical course and without risk factors, a short course of 5 days is recommended, and in children aged less than 2 years, courses of 7–10 days. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: B. Vote: 16 in agreement, 1 abstained (IJH), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 94%.

- •

The duration of antibiotherapy should be individualised (especially in patients with an insidious course or at risk of complications), always taking into account the response to treatment. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

The individualization of antibiotherapy is particularly important in patients allergic to amoxicillin and should be based in the results of culture whenever collection of a sample is indicated. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 16 in agreement, 1 abstained (IJH), 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 94%.

- •

The presence or absence of IgE-mediated allergy to amoxicillin, the severity of the allergy and the clinical course should guide therapeutic decision-making. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

The first step in the management of recurrent AOM should be the detection of predisposing factors, promoting protective factors and avoiding risk behaviours. Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: A. Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.

- •

The approach to the management of recurrent AOM should be individualised based on the characteristics of the patient: surgery in children aged less than 2 years in whom the disease is causing functional impairment in language or hearing and persistent OME (quality of evidence: I. Strength of recommendation: A), antibiotic prophylaxis in children aged less than 2 years in whom the disease is causing functional impairment in language or hearing and with high surgical risk (Quality of evidence: I. Strength of recommendation: A) and watchful waiting in children aged more than 2 years (Quality of evidence: II. Strength of recommendation: B). Vote: 17 in agreement, 0 abstained, 0 in disagreement. Level of consensus: 100%.