There is evidence of the high incidence of neurological abnormalities in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD). Despite this, perioperative neuromonitoring strategies and long-term follow-up protocols are not standardized in Spain.

ObjectiveThe aim of our study was to describe current clinical practice in neuromonitoring, neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental follow-up in patients with CHD in Spanish hospitals that perform paediatric cardiac surgery (PCS).

Material and methodWe conducted a survey by adapting a questionnaire originally developed by the European Association Brain and Congenital Heart Disease Consortium to collect data on aspects such as the implementation of perioperative neuromonitoring and the type of neuroimaging techniques and neurological follow-up performed. The questionnaire was distributed to the 19 Spanish hospitals that perform PCS.

ResultsWe received responses from 17 centres. Eighty-eight percent performed some type of preoperative neuroimaging and 81% postoperative monitoring. The most widely used technique was transfontanellar sonography. Fifty-six percent of the centres used some form of intraoperative neuromonitoring, most frequently near-infrared spectroscopy. Nineteen percent had an established protocol for the follow-up of these patients and 13% were in the process of developing it.

ConclusionsThere is considerable heterogeneity in neuromonitoring, neuroimaging and neurologic follow-up practices in the management of patients with CHD in hospitals that perform PCS in Spain. These findings highlight the need to pursue a consensus in order to standardise neuromonitoring and neurologic follow-up strategies in children with CHD in Spain.

Existe evidencia de la alta incidencia de alteraciones neurológicas en pacientes con cardiopatía congénita (CC). No obstante, en España, las estrategias de neuromonitorización perioperatorias, así como los protocolos de seguimiento no estan estandarizadas.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este estudio es describir las prácticas clínicas actuales en cuanto a neuromonitorización, neuroimagen y seguimiento del neurodesarrollo en pacientes con CC en los hospitales españoles que realizan cirugía cardíaca pediátrica (CCP).

Material y métodoSe diseñó una encuesta adaptando un cuestionario previamente desarrollado por The European Association Brain and Congenital Heart Disease Consortium, en la que se exploraron aspectos relacionados con la neuromonitorización peri-cirugía, las técnicas de neuroimagen y el seguimiento neurológico. La encuesta se envió a los 19 hospitales españoles con programa de CCP.

ResultadosDe los hospitales contactados, se obtuvo respuesta de 17. El 88% de los centros realiza algún tipo de neuroimagen pre-cirugia y un 81% post-cirugía. La ecografía transfontanelar es la técnica más utilizada. El 56% de los centros utiliza alguna estrategia de neuromonitorización intraquirúrgica, siendo la espectroscopia de infrarrojo cercano la más utilizada. Solo el 19% de los centros disponen de un protocolo de seguimiento para estos pacientes y el 13% están en proceso de planificación.

ConclusionesExiste una gran heterogeneidad en las prácticas de neuromonitorización, neuroimagen y seguimiento neurológico para pacientes con CC en los centros españoles con CCP. Estos hallazgos subrayan la necesidad de avanzar hacia un consenso que permita estandarizar las estrategias de neuromonitorización y seguimiento neurológico en niños afectos de CC en España.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) occurs in approximately 1 out of every 100 live births. In Spain, approximately 4000 neonates are born with CHD each year, of who 25% require surgery in the first year of life.1 Advances in surgical technique and perioperative management have improved survival rates, so that 85% of these infants can reach adulthood. However, this increase in survival is associated with a high prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders.2–5

In patients with CHD, abnormalities in brain development may be identified from the fetal stage.6 Thirty percent of infants with CHD have white matter lesions (WMLs) similar to those observed in preterm infants.7 Fetuses with severe CHD have more immature brains, which increases the risk of postoperative neurologic complications or perioperative hemodynamic instability.8 In addition, these perioperative neurologic complications are associated with a prolonged length of stay and increase the risk of neurobehavioral and learning disorders.8–12

Although some countries have implemented guidelines for the neurodevelopmental follow-up of this population,13 there is no consensus at the European level,14 and follow-up in Spain is heterogeneous.

With the aim of obtaining a global perspective on current clinical practice, we conducted a survey of Spanish hospitals offering pediatric cardiac surgery (PCS) services, collecting data on neuromonitoring, neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental follow-up protocols.

MethodsWe developed a questionnaire adapted from a similar survey conducted by the European Association Brain and Congenital Heart Disease Consortium14 and distributed it to every hospital in Spain with a PCS program. The data were collected through the REDCap platform (https://www.project-redcap.org/). The questionnaire was submitted in November 2023, and we accepted responses through January 2024 (Supplemental material).

ResultsGeneral informationWe sent the questionnaire to the 19 Spanish hospitals that had a PCS program, of which 17 responded (Fig. 1).

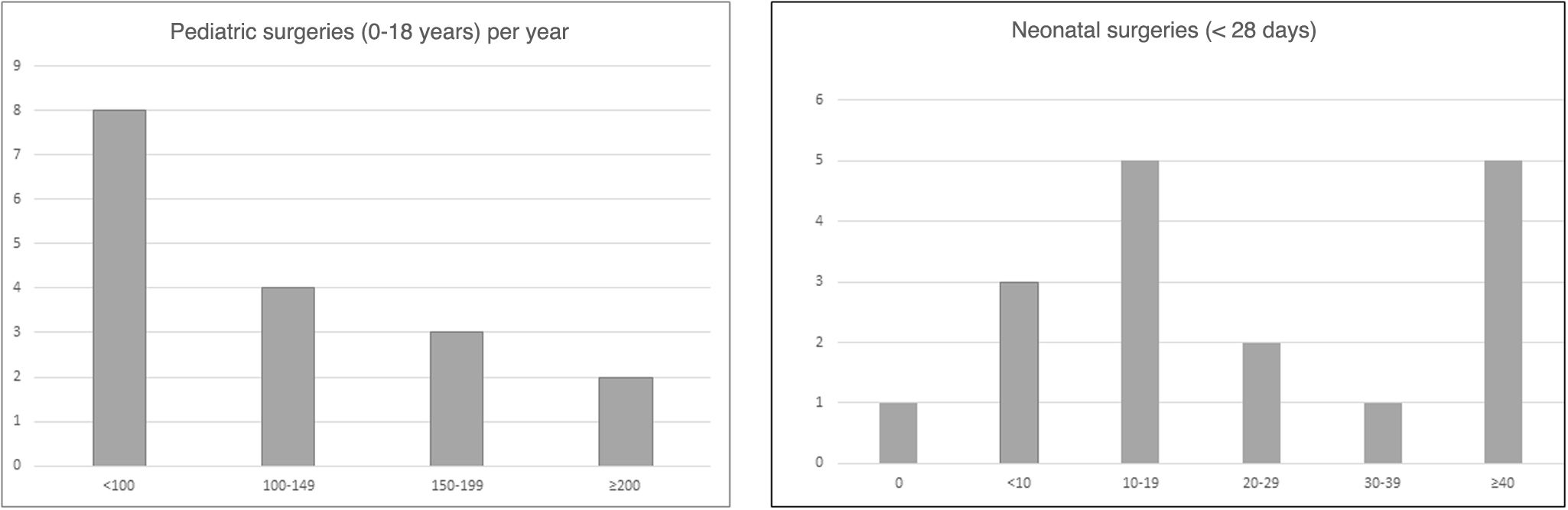

In 2023, a total of 1781 pediatric cardiac surgeries were performed in the 17 participating hospitals, 360 of them in newborns. Extracorporeal circulation was used in 57.7% of the surgeries. Fig. 2 presents the frequency distribution of centers based on the volume of surgeries performed.

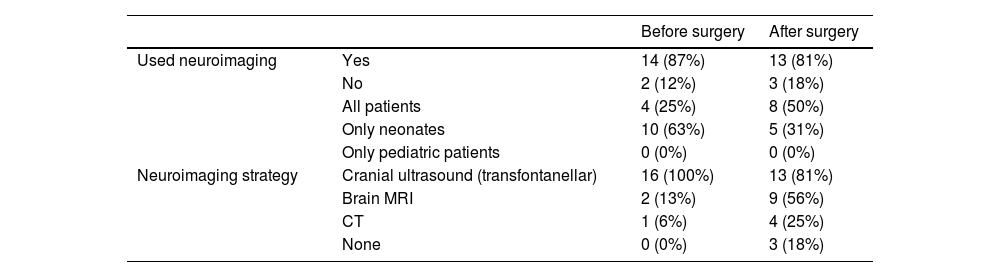

NeuroimagingTable 1 presents the results regarding the use of neuroimaging techniques (cranial ultrasound [CUS], computed tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), for assessment of the central nervous system before and after PCS.

Use of neuroimaging as a tool to assess the central nervous system before and after surgery.

| Before surgery | After surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Used neuroimaging | Yes | 14 (87%) | 13 (81%) |

| No | 2 (12%) | 3 (18%) | |

| All patients | 4 (25%) | 8 (50%) | |

| Only neonates | 10 (63%) | 5 (31%) | |

| Only pediatric patients | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Neuroimaging strategy | Cranial ultrasound (transfontanellar) | 16 (100%) | 13 (81%) |

| Brain MRI | 2 (13%) | 9 (56%) | |

| CT | 1 (6%) | 4 (25%) | |

| None | 0 (0%) | 3 (18%) |

Prior to PCS, 63% of the centers performed a structured neurologic examination (SNE) in newborns (e.g., the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination [HINE]). Among them, the SNE was performed routinely in 40% of the centers, while 50% only performed it if there was some form of clinical concern. The remaining 10% performed it as part of a research protocol.

The centers that performed a preoperative SNE (63%) also performed a SNE in the postoperative period: 30% routinely, 60% only if there were clinical concerns, and 10% as part of a research protocol.

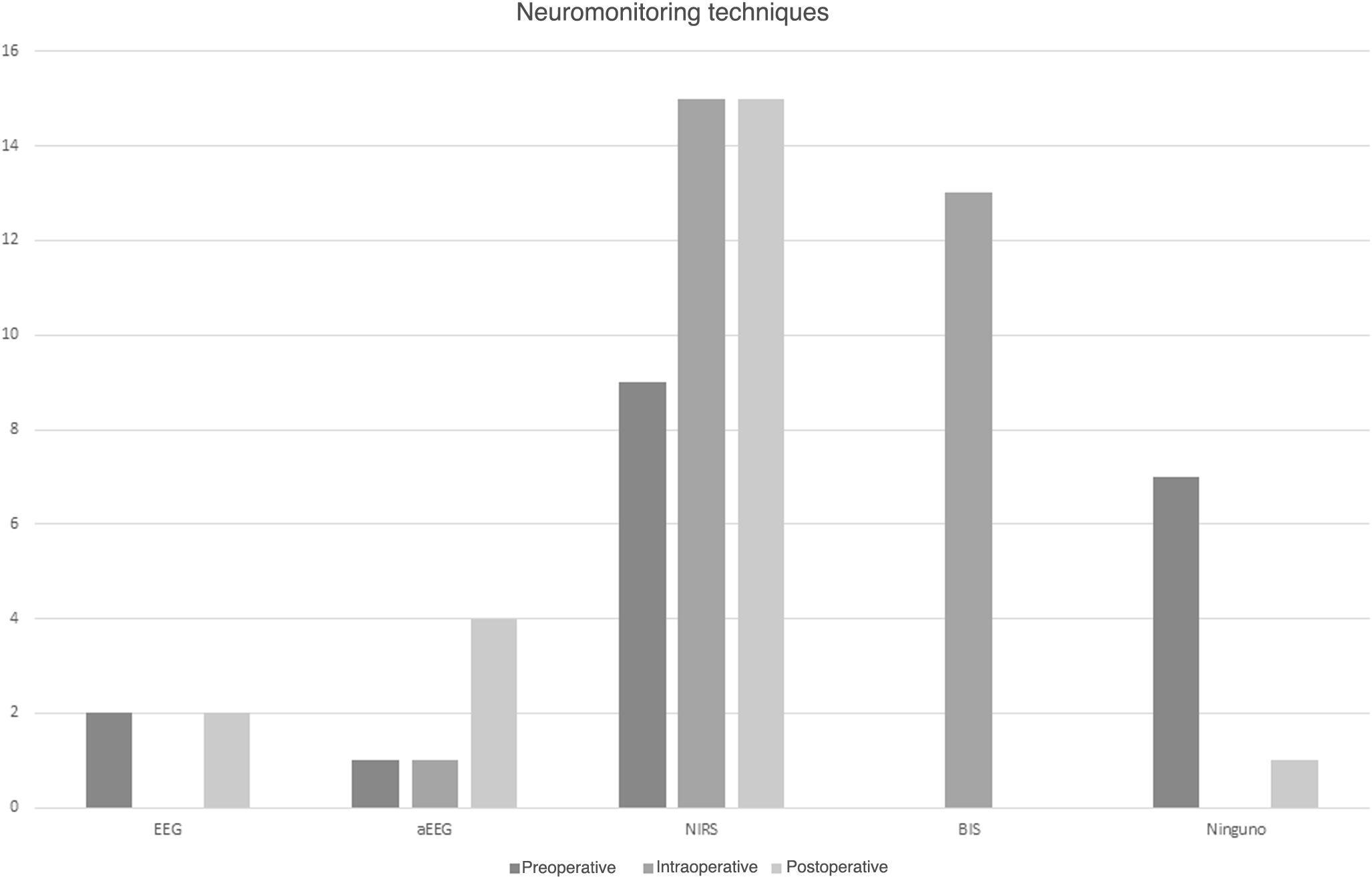

NeuromonitoringFifty-six percent of participating hospitals used neuromonitoring in the preoperative period, and all used near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure the regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rcSO2). Twenty-two percent used conventional electroencephalography (EEG) and 11% amplitude-integrated electroencephalography (aEEG) (Fig. 3).

All centers used neuromonitoring during PCS. Ninety-four percent used NIRS, with the addition of aEEG in 6%. Eighty-one percent used bispectral index monitoring and none of the centers used conventional EEG (Fig. 3).

Ninety-four percent of the centers used neuromonitoring in the immediate postoperative period. All of them used NIRS, 27% aEEG and 13% conventional EEG (Fig. 3).

Follow-up protocol for patients with congenital heart disease (CHD)Nineteen percent of the participating centers had a specific protocol for the neurologic follow-up of patients with CHD. In two of these hospitals, the protocol extended to age 2 years, and in another hospital, to age 6 years. In addition, 2 centers reported they were in the process of developing such a protocol.

DiscussionThis article presents the findings of a survey of Spanish hospitals offering PCS. The results reveal substantial variation in clinical practice between centers, especially in relation to the use of neuromonitoring and neuroimaging techniques and the neurodevelopmental follow-up of patients.

There is growing evidence that patients with CHD tend to have central nervous system abnormalities and WMLs that predate surgery.15–17 For this reason, performance of preoperative imaging is recommended, with MRI currently considered the gold standard.17

In our survey, all hospitals reported the use of CUS, especially in neonates, while MRI was reserved for symptomatic patients or research protocols. Although CUS is the most widely used technique, there is little evidence regarding its predictive value in patients with CHD. A study conducted by Latal et al. found that while CUS could provide relevant information before surgery, its capacity to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes at 12 months was limited.18

Perioperative brain lesions are common in patients with CHD.19 Although postoperative lesions are not the most frequent, several studies have underscored their impact on neurodevelopmental outcomes.20 White matter lesions are associated with unfavorable motor outcomes, a decrease in the intellectual quotient and a higher prevalence of attention problems in school age.21

Among the surveyed centers, CUS was the most frequently used technique for the postoperative evaluation in newborns. Although MRI is the neuroimaging gold standard, it also has limitations, such as the need to transport the patient, its high cost and the difficulty of conducting repeated tests. In addition, it requires that the patient stay still, which in some centers involves the use of sedation and its associated risks.22 According to our survey, 67% of centers carried out MRI in these patients under anesthesia. Some facilities opt for MRI acquisition during natural sleep, a strategy that has been validated, particularly in newborns.23

The SNE is an essential tool for detection of neurologic abnormalities.24 There is evidence that the quality of general movements assessed in the first months of life is correlated to intellectual quotient in school age and can predict neuromotor development through age 9 to 12 years.25,26 In newborns with CHD, instruments such as the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale,27,28 the Einstein Neonatal Neurobehavioral Assessment Scale29,30 and the General Movements Assessment31 have been found to be useful for identification of patients at risk during the postoperative period.32

In Spain, 63% of centers use some form of SNE in newborn infants before and after surgery. However, 31% of centers only use it if there are clinical concerns, a proportion that is substantially larger compared to the 20% reported in European hospitals.14 Performing a SNE before hospital discharge is a simple and efficacious strategy that should be integrated in the routine management of this group of patients.

Neuromonitoring during PCS and the perioperative period is essential in the management of patients with CHD, as it allows anticipation of possible complications.33 When we asked about the neuromonitoring strategies currently in use, monitoring of rcSO2 by means of NIRS was the most widely used method: 56% of centers used it in the preoperative period, 94% during surgery and 94% in the postoperative period. Although the evidence on its usefulness in predicting brain lesions and neurodevelopmental outcomes is contradictory, it continues to be one of the most widely used strategies in the operating room and intensive care units.

Another neuromonitoring strategy that has predictive value in patients with CHD is aEEG, especially in newborns.34 There is evidence of an association between aEEG patterns in the perioperative period and the detection of brain lesions in the perioperative MRI.35 In the postoperative period, the detection of abnormal brain activity is considered a good indicator of brain injury.4 In addition, delayed recovery of the background pattern or the normal sleep-wake cycle has a high predictive value for mortality and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes.36

Although aEEG can help identify newborns at high risk earlier, only 25% of centers in Spain report using it, and rarely used it in pediatric patients. The findings of the aforementioned European study were similar, as only 20% to 30% of centers reported using aEEG in the postoperative period.

There is evidence of a higher prevalence of neurodevelopmental and learning disorders in children with CHD, especially those who require PCS or early palliative care.12,20 Although some countries have established guidelines for the follow-up of patients with neurologic risk, such as extremely preterm infants, specific guidelines for patients with CHD have only been developed in recent years. In 2012, the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics published a scientific statement establishing guidelines for the evaluation, management and follow-up of patients with CHD.13 This guideline, updated in 2024, included a new risk stratification method.37

After this first scientific statement, the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative developed clinical practice guidelines for the neurologic and neurobehavioral follow-up of children with CHD after discharge.38 In Spain, 31% of hospitals currently implement or are in the process of developing a protocol for the neurologic follow-up of these patients, compared to 40% in Europe.14

Although our findings were very similar to those reported for other European countries, the particularities of the Spanish health care system may have played a role in the regional differences observed between autonomous communities. Based on these results, the development of a national consensus-based guideline could contribute to equity in the overall management of these patients.

ConclusionThe findings of this survey evinced substantial heterogeneity in neuromonitoring and neuroimaging practices and the neurodevelopmental follow-up of patients with CHD in Spanish centers that have PCS programs. This evidence can serve as the starting point for the detailed identification of current challenges, at both the local and national level, and the resources that are needed, both human and technical, in addition to an economic and clinical analysis of the present situation in Spain.

Forming a consensus group could lay the groundwork for the collaborative development of a guideline adapted to the particular needs and circumstances of Spanish hospitals offering PCS.

Alexandra Belfi; Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University. Nashville, United States.

Laia Vega: Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Hospital Universitari Dexeus, Grupo Quirónsalud. Barcelona, Spain.

Marta Aguar; Neonatal Unit. Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe. Valencia, Spain.

María Carmen Bravo; Neonatal Unit. Hospital La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Débora Cañizo; Department of Neonatology, BCNatal - Barcelona Center for Maternal Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu - Hospital Clínic, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. ICare4Kits, Cardiovascular Research Group, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain.

Laura Díaz Rueda; Pediatric Intensive Care. Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain.

Cristina Fernández-García; Department of Neonatology. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Barcelona, Spain.

Ángela Ferrer; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña. A Coruña, Spain.

José Manuel González Gómez; Hospital Materno Infantil de Málaga. Malaga, Spain.

Laura Ximena Herrera Castilloz; Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid, Spain.

Jaume Izquierdo-Blasco; Department of Pediatric Intensive Care. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Barcelona, Spain.

Begoña Loureiro; Department of Neonatology, Hospital Universitario Cruces. Barakaldo, Spain.

María Miñambres Rodríguez; Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. Murcia, Spain.

Raúl Montero Yéboles; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Hospital Reina Sofía, Cordoba, Spain.

María Ángeles Murillo Pozo; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Seville, Spain.

Esther Ocete Hita; Pediatric Intensive Care. Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain.

Marta Olmedilla Jódar; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Hospital 12 Octubre. Madrid, Spain.

Daniel Palanca Arias; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric Cardiology Unit. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain.

Rosa Pérez-Piaya Moreno; HM Montepríncipe, Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Madrid, Spain.

Úrsula Quesada; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Seville, Spain.

María Victoria Ramos Casado; Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Hospital 12 Octubre. Madrid, Spain.

Silvia Redondo Blázquez; Department of Pediatric Intensive Care, Hospital Universitario Cruces. Barakaldo, Spain.

Alba Ribas; Department of Neonatology, BCNatal - Barcelona Center for Maternal Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu - Hospital Clínic, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. ICare4Kits, Cardiovascular Research Group, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain.

Cristina Ruiz-Herguido; Department of Neonatology, BCNatal - Barcelona Center for Maternal Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu - Hospital Clínic, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. ICare4Kits, Cardiovascular Research Group, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain.

Francisco de Asís Sánchez Martínez; Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. Murcia, Spain.

Amelia Caridad Sánchez Galindo; Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid, Spain.

Joan Sánchez de Toledo; Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain. ICare4Kits, Cardiovascular Research Group, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain. Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States.

Eva Valverde; Neonatal Unit. Hospital La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Jose Luis Vazquez; Hospital Ramon y Cajal. Madrid, Spain.

Cristina Yun Castilla; Hospital Materno Infantil de Málaga. Malaga, Spain.

Marta Camprubí-Camprubí; Department of Neonatology, BCNatal - Barcelona Center for Maternal Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu - Hospital Clínic, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. ICare4Kits, Cardiovascular Research Group, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain.