Mesenteric lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangiomas or cystic hygromas, are rare lesions originating from the proliferation of lymphatic vessels in the mesentery.1 They mainly affect children aged less than 5 years and the most frequent location are the head, neck and axillary region, with intraabdominal locations accounting for less than 1–5% of cases.1–4 The clinical presentation varies depending on the size and location of the lesion from the absence of symptoms to acute abdomen (abdominal pain, abdominal distension, signs of peritoneal irritation).4,5 Although recent articles have described management with percutaneous sclerotherapy,1 the first-line treatment continues to be complete surgical resection.3,4 In this article, we describe the approach to the diagnosis and treatment of 2 cases of mesenteric lymphatic malformation managed in our unit.

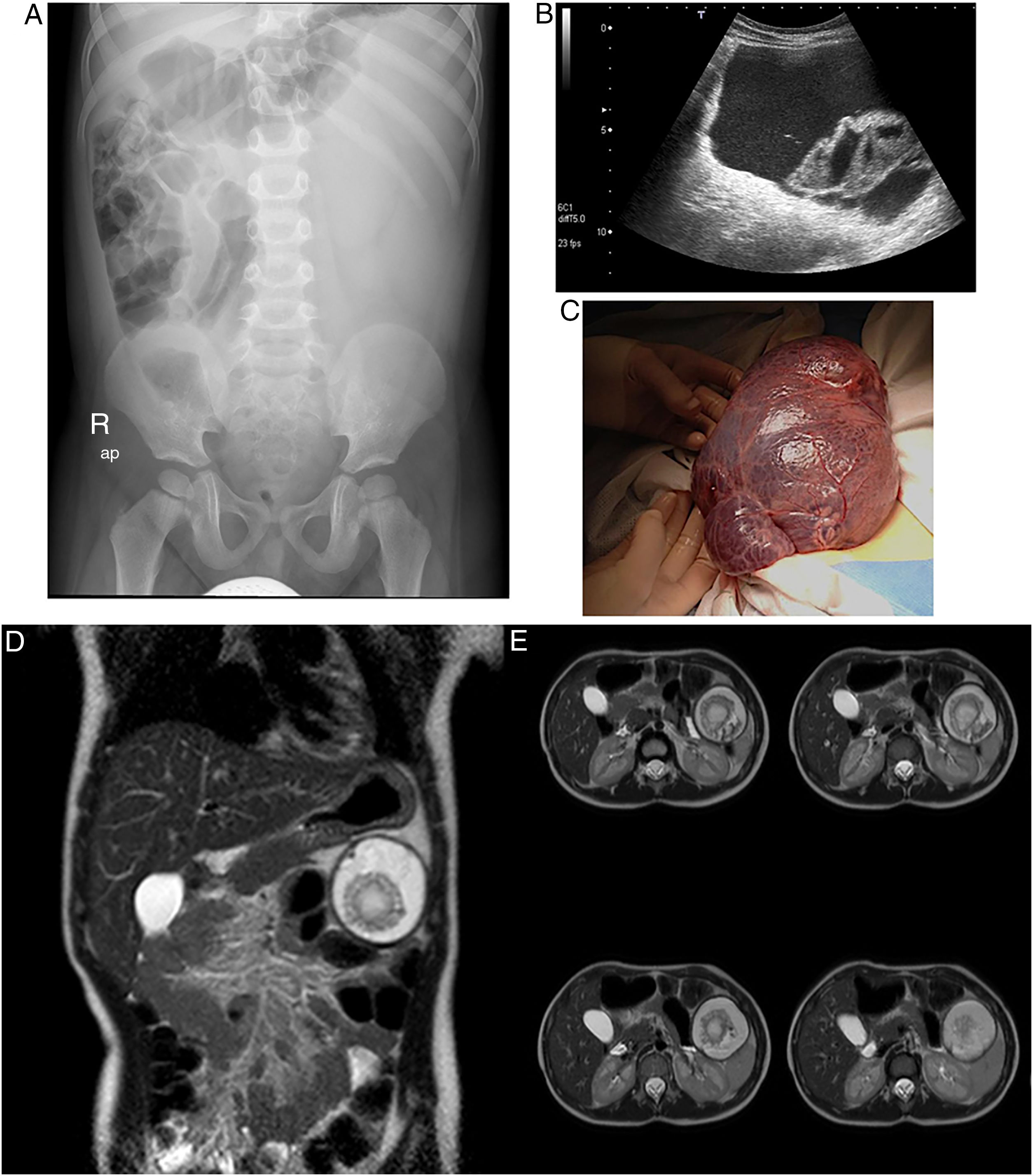

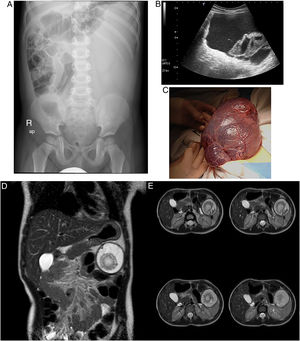

Case ABoy aged 3 years with an unremarkable previous history that sought care in the emergency department for diffuse abdominal pain of 3 days’ duration that exhibited guarding on palpation of the left side of the abdomen. He had been assessed 1 week prior due to a similar episode associated with fever and vomiting that had been managed with conservative treatment. The abdominal X-ray revealed a mass effect in the left side of the abdomen, and the abdominal ultrasound the presence of a large intraabdominal cystic lesion (Fig. 1A and B). As his condition was deteriorating, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy that revealed extensive cystic tumor dependent on the omentum and anchored to the greater curvature of the stomach, which was completely resected (Fig. 1C). The findings of the gross and histological examination led to diagnosis of lymphangioma with haematic content.

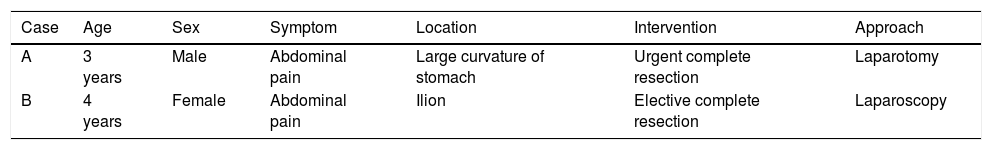

(A–C) Radiological and surgical findings in case A. (A) Abdominal X-ray with the patient in the supine position revealing a mass effect in the left abdomen with displacement of intestinal loops toward the right abdomen. No signs of bowel obstruction. (B) High-resolution grayscale ultrasound image revealing a cystic lesion with echogenic contents, internal septa and another pseudosolid lesion within. (C) Intraoperative image revealing a very large (15×9×3cm) multicystic mass pink in color. (D and E) Radiological findings in case B. Multiphasic contrast-enhanced MRI images in the coronal (D) and axial (E) planes following intravenous administration of gadolinium. Round lesion measuring approximately 5.3cm along all 3 axes located in the left hypochondrium with contents of probable hemorrhagic origin demarcated by a hypointense shape of a capsule or pseudocapsule. No evidence of organ dependence, edema or infiltration of adjacent structures.

Girl aged 4 years assessed in the emergency department for colicky abdominal pain of 5 day's duration associated with vomiting. The patient had had similar episodes before that had resolved satisfactorily with enemas. She underwent an ultrasound examination that revealed a very larger multicystic lesion in the left hypochondrium. In this case, the patient was clinically stable, which allowed performance of a magnetic nuclear imaging (MRI) scan to complete the investigation and schedule surgery. The scan revealed a cystic lesion at the level of the mesentery in close contact with the tail of the pancreas (Fig. 1D and E). The patient underwent laparoscopic-assisted resection of the lesion with bowel anastomosis. The pathology report described a benign cystic vascular lesion with immunohistochemical features compatible with lymphangioma (Table 1).

The lesions formerly known as lymphangiomas are currently classified under the term lymphatic malformations and described as cystic vascular anomalies rather than tumors of the lymphatic vessels. They may present in isolation or in the context of systemic disease.6

They are typically present at birth and grow with the child, becoming increasingly noticeable. This leads to diagnosis by age 5 years in 60–90% of cases, and diagnosis in adulthood is rare.3,4

Most cases (95%) involve the lymphatic vessels in the head, neck or axillary region, while abdominal involvement (in the mesenteric or retroperitoneal regions) is rare.1–6 Nevertheless, given the heterogeneity in the terminology used historically to describe them (lymphatic malformation, lymphangioma, cystic hygroma, etc.) and the fact that it may affect both the pediatric and the adult populations, it is very likely that its incidence is somewhat underestimated.6

The most widely accepted theory on the etiology of these malformations is the “blind sac” hypothesis, according to which these are congenital lesions resulting from sequestrations of lymphatic tissue that do not communicate with the lymphatic system during embryonic development, leading to dilatation of the vessels and formation of a cystic mass as the lymph accumulates.4 However, different authors of articles in the literature have proposed an association with specific factors such as radiation exposure, abdominal trauma, surgery or inflammation, among others.3,4

Most identified cases are painless masses growing in proportion to the child, but in some instances these malformations can cause complications such as infection, rupture, bowel obstruction, volvulus or spontaneous bleeding,2,6 making it a surgical emergency, as occurred in case A presented here. The latter cases typically present as acute abdomen, and the most frequent symptom is abdominal pain.

Ultrasonography is the gold standard of imaging for the initial evaluation and can be supplemented with computed tomography or MRI for a more thorough definition of the lesion if the condition of the patient allows it. In many cases, the definitive diagnosis is based on the histological findings.4,6

Surgical treatment involves the complete resection of the lesion and is associated with favorable long-term outcomes and a low risk of malignant transformation or recurrence.1,3

Although lymphatic malformations manifest infrequently as acute abdomen, they should not be excluded from the differential diagnosis of this clinical picture, especially in case of detection of a palpable abdominal mass.

Please cite this article as: Merino-Mateo L, Morante Valverde R, Redondo Sedano JV, Benavent Gordo MI, Gómez Fraile A. Malformación linfática mesentérica: una causa poco frecuente de abdomen agudo. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;92:49–51.