Enterovirus (EV) frequently causes outbreaks of infection in children in spring and summer. Although it usually produces mild illness, there are also cases with severe neurologic involvement (encephalitis, rhombencephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis and autonomic dysfunction with pulmonary oedema) that may cause lifelong sequelae or death. The serotypes associated with the most severe cases are A71 and D68.1–6 We describe the cases of the patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Madrid in May 2016 following the outbreak of EV infection with severe neurologic involvement in Catalonia in the same year.1

We conducted a prospective descriptive study of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics, the diagnostic tests performed and the outcomes of patients admitted with suspected EV infection and severe neurologic symptoms (Table 1).

Summary of clinical characteristics, diagnostic tests, treatment and outcomes for each patient.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | Patient 10 | Patient 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 25 | 49 | 26 | 22 | 29 | 32 | 25 | 48 | 14 | 11 | 26 |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Systemic manifestations | |||||||||||

| Fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Irritability | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Skin and mucosal involvement | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hand-foot-mouth-like rash | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Enanthem | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Neurologic manifestations | |||||||||||

| Onset (days from onset of systemic symptoms) | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Somnolence | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ataxia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Leve |

| Myoclonus | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Tremors | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Convulsive seizures | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Flaccid paralysis | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Initial suspicion | No |

| Involvement of cranial nerves III-XII | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dysautonomia | |||||||||||

| Altered breathing pattern | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Neurogenic pulmonary oedema | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cardiac dysfunction | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| High blood pressure | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brain and spine MRI | Involvement of hindbrain and spinal cord | Involvement of brainstem, medulla and cervical spinal cord | Cervical transverse myelitis | Involvement of cervical spine and conus medullaris | Involvement of dentate nucleus and spinal cord through segment D1 | Possible but unclear hyperintensity at the level of the C3–C6 segments and periaqueductal white matter | Lesions in left thalamus and cerebral peduncles and cervical myelitis | Hyperintensity in cerebral peduncles, periaqueductal brain matter and cervical spine through segment C6 | Tracer uptake in the cervical and dorsal spine and conus medullaris | Mild hyperintensity in dentate nucleus | Not performed |

| Enterovirus serotype | Nontypeable | A | A 71 | A 71 | A 71 | A 71 | B | – | Echo 32 | Nontypeable | A 71 |

| Treatment | |||||||||||

| Days from onset of symptoms | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 4 | No treatment |

| IVIG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Corticoids | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Fluoxetine | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Outcome | |||||||||||

| PICU stay (days) | Yes (12) | Yes (11) | Yes (2) | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (2) | No |

| Mechanical ventilation (days) | Yes (7) | Yes (7) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (2) | No |

| Length of stay (days) | 26 | 25 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| Early sequelae | Altered sleep and irritability | Tremors and irritability | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

We analyzed 11 cases, of which 10 were confirmed, defined as presenting with acute neurologic manifestations of encephalitis, rhombencephalitis and/or acute paralysis with compatible findings on MRI examination and detection of enterovirus by PCR analysis of a nasopharyngeal or rectal swab sample in the absence of evidence of a different aetiological agent. One was a probable case, suspected based on compatible clinical manifestations and results from diagnostic tests, but without microbiological confirmation.

All the patients were previously healthy. The median age was 26 months (interquartile range [IQR], 22–32) and there was a predominance of the female sex (6/11). We did not find an apparent epidemiological association between the different cases. The symptoms at onset were irritability (11/11), fever (10/11) and skin and mucosal involvement (8/11). Neurologic symptoms developed a median of 3 days after the onset of systemic symptoms (IQR, 2–4), and the most common were ataxia (11/11), somnolence (10/11), tremors (9/11) and myoclonus during sleep (7/11). Only 2 patients had symptoms of brainstem involvement, while flaccid paralysis was initially suspected in 1 (due to areflexia and need for mechanical ventilation) but eventually ruled out due to the quick resolution of symptoms within 24h. Four patients were admitted to the PICU due to dysautonomia and cardiac dysfunction.

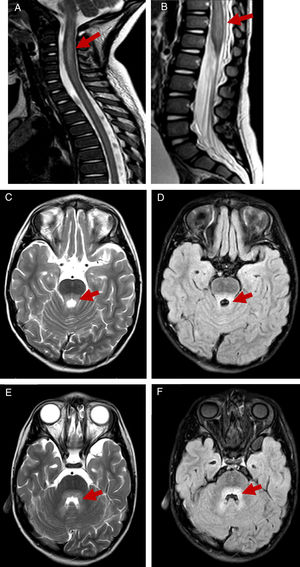

All patients underwent a lumbar puncture, and subsequent examination of the sample revealed pleocytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid in 9 out of 11 patients, with lymphocytic predominance in 7. A MRI scan was performed in 10 patients, revealing rhombencephalitis in 8 (associated with myelitis in 7) and isolated myelitis in 2 (Fig. 1). Since a high proportion of patients presented with somnolence and irritability, an encephalogram (EEG) was performed in 10, revealing slow wave activity in 9. The results of 9 brainstem auditory evoked response tests in patients with manifestations or MRI evidence of brainstem involvement and the 3 electromyograms performed in patients with significant spinal cord involvement were normal.

T2-weighted and FLAIR MR images showing hindbrain involvement with myelitis. T2-weighed images showing hyperintensity on at the level of the cervical spine until segment C6 in patient 2 (A) and significant thickening of the conus medullaris in patient 4 (B). Hyperintensity on T2-weighted and FLAIR MR images at the level of the posterior pons and surrounding the fourth ventricle in patient 2 (C–F).

Enterovirus was detected in rectal swab samples (10/11) and nasopharyngeal swab samples (5/9) by PCR (GeneXpert®) in our hospital, and subsequently typed in samples submitted to the Centro Nacional de Microbiología. It was not detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood samples in any patient. The most frequent serotype was A71 (5/10), while serotype D68 was not detected in any case. The 10 patients classified as having moderate illness (significant somnolence) or severe illness (clinical manifestations or neuroimaging evidence of brainstem or spinal cord involvement) received early intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy (within 24–48h from admission) in adherence with the treatment protocol applied in previous outbreaks.1,2 All of them received IVIG (1g/kg/day for 2 days), combined with administration of boluses of IV methylprednisolone (30mg/kg/day for 3 days) in patients with severe disease. Only patients admitted to the PICU received fluoxetine (0.3mg/kg/day), which was prescribed off-label on account of its in vitro activity and had no clear beneficial effects.

Two of the patients with severe disease had immediate sequelae that resolved after 3 months, and all patients remained asymptomatic at 12 months’ followup. The diagnostic tests repeated during followup included 4 EEGs that showed normalization of wave patterns and 2 MRI scans, of which 1 was unremarkable and 1 had features indicative of persistent myelitis.

In conclusion, we present a group of cases of EV infection with neurologic involvement linked in time, in which the most frequent type of involvement was rhombencephalitis. The clinical presentation was similar to the one described in other studies.1–3 The serotype detected most frequently was A71. As happened in the outbreak in Catalonia, while the initial presentation of some of the patients was severe, none died and all had favourable outcomes with no sequelae,1 which was not the case in other countries.2,3,6

Given the potential severity of neurologic involvement in enterovirus infection and that an outbreak of this magnitude had not been described in Spain until 2016, we believe that reporting the cases occurred in our country is relevant. This could help identify similar cases earlier, improving the initial management (especially supportive care) of an infection that can lead to death in the first 24h from the onset of neurologic symptoms.

Please cite this article as: Leal Barceló AM, Carrascosa García P, Rincón López EM, Miranda Herrero MC, Navarro ML. Brote de infección por enterovirus causantes de afectación neurológica grave en un hospital terciario. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:378–381.

Previous presentation: This study was presented as an oral communication at the XX Annual Meeting of the Sociedad de Pediatría de Madrid y Castilla-La Mancha, September 30, 2016, Oropesa, Spain.