The increased survival of congenital heart diseases has led to an increase in the long-term use of oral anticoagulants (OACs) in children.1 The most frequently used type are vitamin K antagonists, which are characterised by their narrow therapeutic margin and the need for frequent monitoring of the international normalised ratio (INR). Their management in children is complicated by problems inherent in this age group, such as inconsistent nutritional intake or infectious diseases.1,2

Treatment quality is assessed based on the time in therapeutic range (TTR), the percentage of time that the patient maintains an INR within the target range. While values of less than 60% are considered ineffective, greater values are associated with a decreased risk of bleeding episodes and thrombotic events.1,3

There is evidence that OAC self-management programmes achieve increases in TTR in children.1,4,5 We present the first paediatric case series analysed in Spain to assess the impact of the introduction of an AOC therapy self-monitoring programme.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study between January 2015 and May 2017 in patients aged 1 to 17 years. Our aim was to compare the TTRs after the introduction of a self-monitoring programme with the TTRs achieved in the previous year.

We collected data for demographic variables, age, indication for OACs, target therapeutic range, INR values, frequency of monitoring, date of initiation of self-monitoring, incidence of thrombotic events or bleeding episodes and reasons for variations of INR above 5 or below 1.4.

After they agreed to participate in the study, children and their caregivers received training on the use of the following: CoaguChek® XS portable system (Roche Diagnostics), tables to guide self-dosing of AOCs, and an online platform (TAONet®) and a mobile application (TAONet® Me) to report results to health care providers in real time.

The TTR was estimated using the Rosendaal linear interpolation method, which reduces the impact of multiple INR values over a short period of time. Applying the methodology used in other studies, we calculated the TTR based on the exact target INR with the addition of a 0.2 unit margin on either side, as the dose is usually not adjusted when the INR remains within these values.1,3 We assessed association by means of the Student's t test for paired samples after verifying that the data followed a normal distribution. We considered results with a p-value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

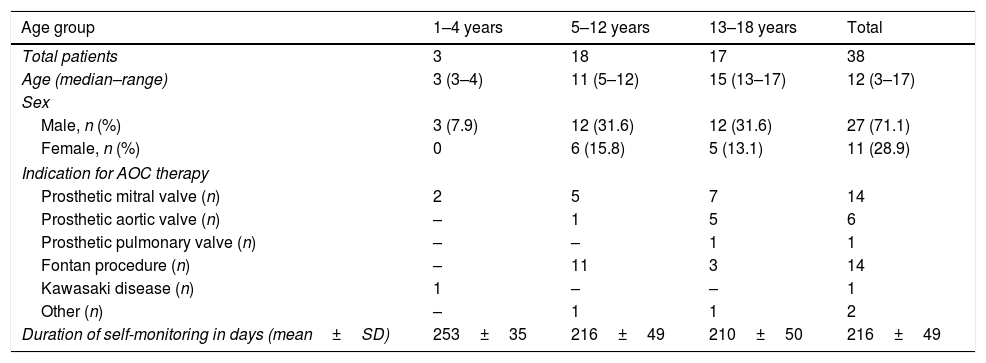

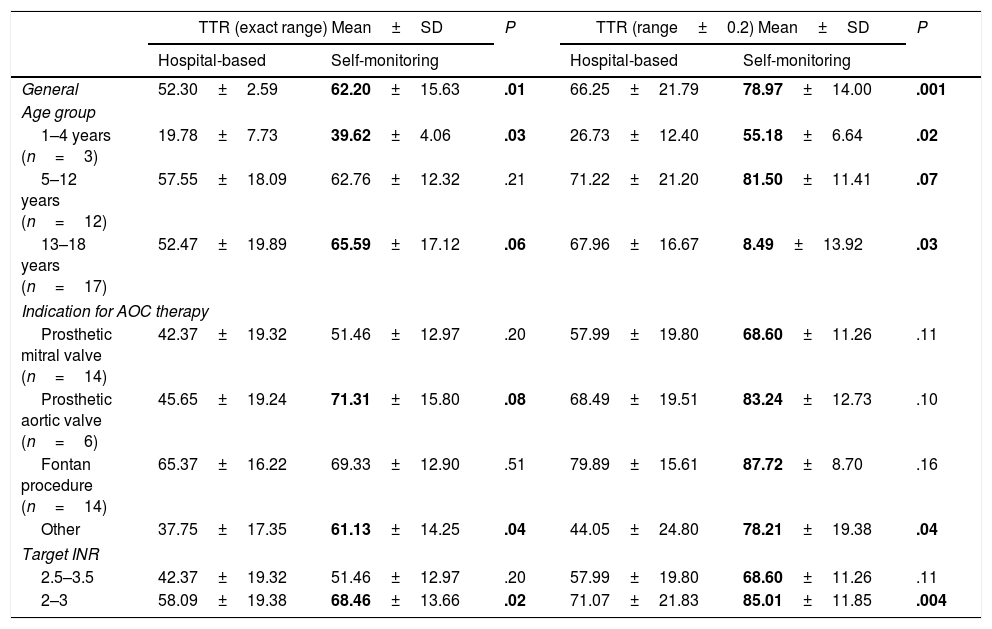

We included 38 patients in the study. All were receiving treatment with acenocoumarol. Table 1 summarises the relevant information about the cohort. Table 2 presents the TTR results by age, underlying disease and target INR. Regarding adverse effects of treatment, 1 patient aged 15 years developed menorrhagia in the hospital-based monitoring period. None of the patients experienced thrombotic events. The most frequent reasons for deviations from the target INR were infectious disease (30%) and non-adherence to treatment. In children aged less than 5 years, infectious diseases explained the deviation from the target in 71% of cases.

Demographic characteristics of patients, underlying disease that was the reason for treatment with AOC and duration of self-monitoring in days at the time of the study.

| Age group | 1–4 years | 5–12 years | 13–18 years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 3 | 18 | 17 | 38 |

| Age (median–range) | 3 (3–4) | 11 (5–12) | 15 (13–17) | 12 (3–17) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 3 (7.9) | 12 (31.6) | 12 (31.6) | 27 (71.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 0 | 6 (15.8) | 5 (13.1) | 11 (28.9) |

| Indication for AOC therapy | ||||

| Prosthetic mitral valve (n) | 2 | 5 | 7 | 14 |

| Prosthetic aortic valve (n) | – | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Prosthetic pulmonary valve (n) | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Fontan procedure (n) | – | 11 | 3 | 14 |

| Kawasaki disease (n) | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Other (n) | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Duration of self-monitoring in days (mean±SD) | 253±35 | 216±49 | 210±50 | 216±49 |

AOC, oral anticoagulant; SD, standard deviation.

Mean, standard deviation and statistical significance of the comparison of times in therapeutic range before and after the introduction of the self-monitoring programme, calculated for the exact INR target range and the INR range expanded by ±0.2 units.

| TTR (exact range) Mean±SD | P | TTR (range±0.2) Mean±SD | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-based | Self-monitoring | Hospital-based | Self-monitoring | |||

| General | 52.30±2.59 | 62.20±15.63 | .01 | 66.25±21.79 | 78.97±14.00 | .001 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 1–4 years (n=3) | 19.78±7.73 | 39.62±4.06 | .03 | 26.73±12.40 | 55.18±6.64 | .02 |

| 5–12 years (n=12) | 57.55±18.09 | 62.76±12.32 | .21 | 71.22±21.20 | 81.50±11.41 | .07 |

| 13–18 years (n=17) | 52.47±19.89 | 65.59±17.12 | .06 | 67.96±16.67 | 8.49±13.92 | .03 |

| Indication for AOC therapy | ||||||

| Prosthetic mitral valve (n=14) | 42.37±19.32 | 51.46±12.97 | .20 | 57.99±19.80 | 68.60±11.26 | .11 |

| Prosthetic aortic valve (n=6) | 45.65±19.24 | 71.31±15.80 | .08 | 68.49±19.51 | 83.24±12.73 | .10 |

| Fontan procedure (n=14) | 65.37±16.22 | 69.33±12.90 | .51 | 79.89±15.61 | 87.72±8.70 | .16 |

| Other | 37.75±17.35 | 61.13±14.25 | .04 | 44.05±24.80 | 78.21±19.38 | .04 |

| Target INR | ||||||

| 2.5–3.5 | 42.37±19.32 | 51.46±12.97 | .20 | 57.99±19.80 | 68.60±11.26 | .11 |

| 2–3 | 58.09±19.38 | 68.46±13.66 | .02 | 71.07±21.83 | 85.01±11.85 | .004 |

Statistically significant results presented in boldface.

AOC, oral anticoagulant; INR, international normalised ratio; SD, standard deviation; TTR, time in therapeutic range.

In our case series, there was a significant overall improvement in TTR after the introduction of the self-monitoring programme: children with a target INR range of 2 to 3 achieved TTRs higher than 85%. In particular, children with a total cavopulmonary shunt (Fontan procedure) achieved a mean TTR of 87.7%. These results are consistent with those published by other groups.1–5 Jones et al. reported that 69.2% of tests conducted at home were strictly within the prescribed TTR in 93 paediatric patients receiving warfarin.1 Other authors have published similar results,5 although no other group has come close to the 92% reported by the Canadian group.4

Younger patients, however, had TTRs lower than 60%. We attributed these results to variations caused by intercurrent infections and to the higher target INR required by most of the patients (2/3) aged less than 5 years, as higher target ranges have also been associated with poorer treatment control in previous studies.1,6 Nevertheless, the TTRs achieved were significantly improved compared to the previous period, which led to a positive evaluation of the self-monitoring programme.

Since we compared a single group of patients at 2 different times, we cannot rule out the possibility that all or some of the observed improvement in outcomes was due to other causes. However, both previous literature1–6 and our results suggest that the increased monitoring frequency and the empowerment of patients and their parents to assume the management of treatment were the most likely causes of the observed changes.

Please cite this article as: Berrueco R, Benedicto C, Ruiz-Llobet A, Gassiot S, Català A. Programa de autocontrol del tratamiento anticoagulante oral con antagonistas de la vitamina K en pacientes pediátricos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:381–383.