Breast masses are rare in girls and female adolescents, and they exceptionally have a malignant aetiology. The most frequent diagnosis in these masses is juvenile fibroadenoma. When its size exceeds 5cm, it is called giant fibroadenoma (GFA), a large-sized benign tumour with rapid growth. The differential diagnosis of GFA includes inflammatory processes, benign proliferative lesions and phyllodes tumour.1,2 Due to the lack of specific clinical guidelines for its correct diagnosis and treatment, the management of breast masses may pose difficulties.

We conducted a retrospective study of the breast masses larger than 5cm managed between 2000 and 2017 in a paediatric hospital. We collected data on the clinical characteristics and the diagnostic tests and treatment used in each case. The data was retrieved from the health records adhering to the protocols established by the hospital.

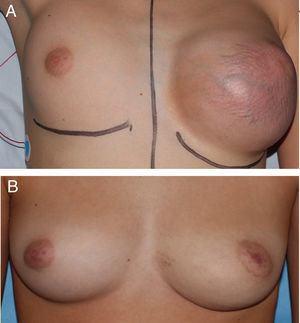

We present 4 cases of macromastia in patients with a median age of 15.3 years (range, 11.9–16.2), at Tanner stage 5 of pubertal development that sought care after developing a unilateral breast mass that was painless and growing quickly. On physical examination, the masses were painless, mobile, unattached to deeper tissues and with hypervascularization at the skin level (Fig. 1A). None of the patients had nipple discharge or local lymphadenopathy.

Sonographic examination of the breast revealed hypoechoic, lobulated masses with well-defined margins, in cases 1 and 3 with superficial hypervascularization. The findings in all patients were compatible with GFA or phyllodes tumour. The assessment of cases 1 and 4 included an MRI examination that revealed heterogeneous lesions that appeared isointense and hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with no signs of infiltration. The radiological findings were not conclusive.

The diagnosis of GFA was confirmed after excision of the masses (Fig. 2); the maximum tumour diameter ranged between 5 and 14.5cm and the mean weight was 1500g. The surgical technique used in cases 1, 2, and 3 was simple excision (Fig. 1B). In case 4, excision was followed by placement of a filled tissue expander that was emptied gradually with the purpose of helping the skin recover its elasticity progressively. We ought to mention that none of the patient experienced postoperative complications and all had good outcomes.

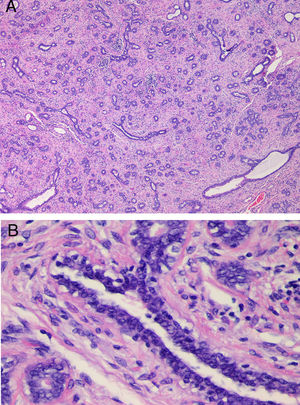

(A) Histological examination in case 3. Fibroepithelial proliferation with areas of pericanalicular and intracanalicular growth. No evidence of marked stromal growth, fat infiltration or cleft-like spaces. (B) Detail of Fig. 2A (H&E stain, 4×), showing a mildly hyperplastic epithelium and a stroma without cytological atypia or mitotic activity.

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics, radiological and pathological findings and final diagnosis for each case.

Clinical, radiological and gross and histological characteristics of the cases.

| Case | Race | Age (years) | Time elapsed from onset (months) | Localisation | Suspected diagnosis after ultrasound | Diagnosis after FNABa/CNBb Excisional biopsyc | Type of surgery | Gross tumour volume (cm) | Final diagnosis after analysis of specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caucasian | 11.9 | 7 | Unilateral | GFA/phyllodes tumour | Virginal breast hypertrophyc | Simple excision | 14.5×11.5×7 | GFA |

| 2 | Caucasian | 16.2 | Not documented | Unilateral | GFA/phyllodes tumour | GFAa | Simple excision | 5×4×2 | GFA |

| 3 | Caucasian | 14.9 | 1 | Unilateral | GFA/phyllodes tumour | GFAb | Simple excision | 10×8×8.5 | GFA |

| 4 | Black | 15.7 | 24 | Unilateral | GFA/phyllodes tumour | GFAa | Simple excision + tissue expansion | 12×10×3 | GFA |

CNB, core needle biopsy; FNAB, fine needle aspiration biopsy; GFA, giant fibroadenoma.

Giant fibroadenomas are masses characterised by a diameter of more than 5cm and rapid growth, and they are an infrequent type of fibroadenoma that accounts for 0.5–2% of the total cases.1–3 Their aetiology is unknown, although it has been hypothesised that they may be caused by increased sensitivity to oestrogen.1 In most cases, the mass develops during pubertal development around the time of menarche. This could be explained by the high cellular activity of the lobules from the onset of puberty to approximately age 25 years.4,5 The patients in our study were aged less than 17 years, which was consistent with the description of Sosin et al.2

The differential diagnosis of GFA includes inflammatory processes, benign proliferative lesions (hamartoma, lipoma, virginal or juvenile hypertrophy of the breast and pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia [PASH]) and phyllodes tumour.2,3 The main diagnosis that needs to be excluded is phyllodes tumour, which corresponds to fewer than 1% of all breast tumours. Its clinical and sonographic features may be indistinguishable from those of GFA and even virginal hypertrophy or PASH. Virginal hypertrophy is characterised by a rapid growth of breast tissue due to hypersensitivity to estrogens.5 In very rare cases, breast masses correspond to lipoma, hamartoma or PASH.4–6 The histological differential diagnosis includes virginal hypertrophy of the breast, breast hamartoma and, most importantly, phyllodes tumour. Fine-needle puncture aspiration biopsy is not useful to discriminate between these diseases. It is extremely difficult to distinguish GFA and phyllodes tumour in a core needle biopsy (CNB), and one study found that up to 25% of phyllodes tumours had initially been classified as fibroadenomas based on the CNB histology.7 Some authors have proposed histological features that would indicate surgical excision: increased stromal cellularity compared to a conventional fibroadenoma in more than 50% of the submitted tissue sample, stromal overgrowth viewed in a 10× microscopic field, stromal fragmentation and entrapment of fat in the lesion.6

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging test for assessment of a breast mass during adolescence. Fibroadenomas appear as a round or oval mass, isoechoic or hypoechoic and with well-defined borders. Doppler ultrasound reveals hypervascularization in up to 80% of cases, and was found in 50% of our patients. The sonographic appearance may be the same in cases of virginal hypertrophy, PASH or phyllodes tumour, which calls for histological examination in masses larger than 5cm or exhibiting rapid growth.7–9 Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast is not used routinely. However, it may be useful to define the lesion better before surgery.7

The treatment of fibroadenomas depends mainly on their size. For those with a diameter of less than 5cm in adolescents, treatment is conservative, as the risk of malignancy is nearly non-existent in the group aged less than 20 years. In cases of suspected GFA, complete excision of the mass is indicated for gross and histological examination, as GFA cannot be differentiated from some other masses, mainly phyllodes tumour, based on the clinical presentation and radiological features.5

If possible, surgery must spare healthy breast tissue and the nipple-areolar complex. Based on our results and the evidence published in the literature, simple excision, where the case allows it, is the treatment of choice on account of the low rate of postsurgical complications and the excellent cosmetic outcomes.10

In conclusion, ultrasound is the first-line imaging test for assessment of a mass in the breast, and a full gross and histological examination is necessary in masses with diameters of more than 5cm and/or exhibiting rapid growth, as fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsies are not useful in this type of lesion. The surgical treatment of choice is simple excision.

Please cite this article as: Corredor Andrés B, Márquez Rivera M, Lobo Bailón F, González Meli B, Azorín Cuadrillero D, Muñoz Calvo MT, et al. Fibroadenoma gigante de mama en adolescentes: procedimientos diagnóstico-terapéuticos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89:381–383.