There is evidence that the percentage of adolescents that practice testicular self-examination is low.

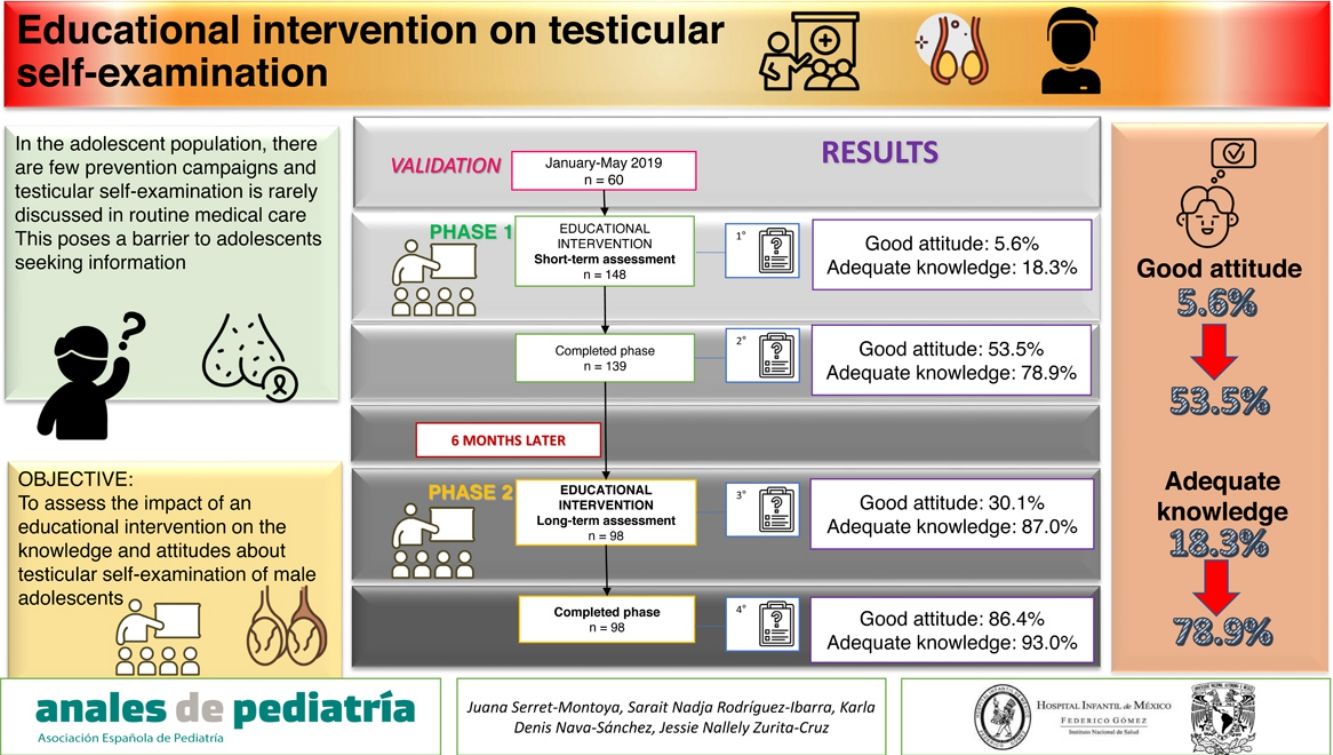

ObjectiveTo assess the short-term and long-term (6 months) impact in male adolescents of an educational intervention on the knowledge of testicular self-examination and attitude toward it.

MethodsWe conducted a quasi-experimental pre-test post-test study in male adolescents. A questionnaire was validated to assess knowledge on testicular self-examination and attitudes towards it (awareness, intentions, and behaviour). The educational intervention was group-based and consisted in an instructional talk with the aid of diagrams and brochures. The questionnaire was administered before and after the intervention. A follow-up was scheduled 6 months later, and the talk was delivered again, with administration of the questionnaire before and after.

ResultsThe study included 139 adolescents with a median age of 14 years. We found an improvement in knowledge (18.3% vs 78.9%; P = 0.02) and attitude (5.6% vs 53.5%; P = 0.02) after the initial intervention. At the 6-month follow-up (n=98), there was no change in knowledge (87.0% vs 93.0%; P = 0.671), but attitude improved after the second intervention (58.0% vs 78.0%; P = 0.009).

ConclusionAn educational intervention on testicular self-examination improved the proportion of adolescents with an adequate attitude (5.6% vs 53.5%) and adequate knowledge (18.3% vs 78.9%). The repetition of the intervention at 6 months increased the proportion of adolescents with an adequate attitude (53.5% vs 86.4%).

Se ha descrito que la autoexploración testicular se realiza en un bajo porcentaje de los adolescentes.

ObjetivoEvaluar el impacto de una maniobra educativa a corto y largo plazo (6 meses) sobre el conocimiento y actitud de los adolescentes varones en la autoexploración testicular.

MétodosSe realizó un cuasi-experimento, antes y después en adolescentes varones. Se validó un cuestionario para evaluar el conocimiento y la actitud (conciencia, intenciones y comportamiento) sobre la autoexploración testicular. La maniobra educativa consistió en una charla informativa de manera grupal incluyendo esquemas y folletos. Se les aplicó el cuestionario antes y después de la maniobra educativa. Se citaron a los 6 meses posteriores y se les dio nuevamente la charla aplicándose un cuestionario antes y después de la misma.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 139 adolescentes con una mediana para la edad de 14 años. El conocimiento (18.3% vs 78.9% p=0.02) y la actitud (5.6% vs 53.5% p=0.02) mejoró posterior a la primera charla informativa. A los 6 meses de seguimiento (n=98) el conocimiento no se modificó (87.0% vs 93.0% p=0.671); sin embargo, la actitud superó posterior a la segunda charla (58.0% vs 78.0% p=0.009).

ConclusiónUna maniobra educativa sobre la autoexploración testicular mejoró la proporción de una adecuada actitud (5.6% vs 53.5%) y conocimiento (18.3% vs 78.9%) en los adolescentes. El reforzamiento de la maniobra a 6 meses mejora la proporción de una adecuada actitud (53.5% vs 86.4%).

Testicular cancer is the most frequent type of cancer in men aged 15–40 years, with detection of 9 cases per 100 000 male individuals per year in Europe1. The main risk factors described in the literature are cryptorchidism, genitourinary anomalies and endocrine dysfunction, among others2. The incidence of testicular cancer is low compared to other forms of cancer affecting male individuals, but it continues to grow worldwide, as the main problem is the lack of dissemination of information regarding its prevention, detection and treatment, contributing to insufficient awareness and implementation of behavioural measures1,3. This is concerning, given that early detection has a substantial impact on survival and the cure rate for testicular cancer is approximately 96% if it is detected in the early stages2,4.

The American Cancer Society recommends testicular self-examination as an effective and cost-free measure to prevent late-stage diagnosis5,6. In light of this, the main goal of promoting testicular self-examination is to improve the efficacy of doctor-patient communication, thereby improving the quality and efficiency of health education7.

Studies in young adults have evinced lack of knowledge regarding testicular self-examination and what to do when a mass is detected, with only 10% of study participants reporting performing testicular self-examinations3,8,9. Other studies have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of comprehensive testicular cancer campaigns with advertising in social networks and mass media, flyers and educational talks that analysed data on age, risk groups, symptoms, performance of self-exams, curability rates and the importance of early detection10–14, and statistically significant changes in behaviour (performance, monthly self-examination, discussion of testicular cancer with a physician, friend or relative and search of information) have been found after educational campaings5,15,16.

There is evidence that performance of testicular self-examination is influenced by attitudes and emotional factors, and anxiety and shame may pose barriers to self-examination17,18; on the other hand, informational talks on testicular self-examination reduced anxiety in young men, increasing the probability of having performed testicular self-examination in the past month15,16.

Interventional studies on testicular self-examination have mostly focused on young adults, whereas few prevention campaigns target the male adolescent population and testicular self-examination is rarely explained in routine medical checkups in this age group, which poses a barrier to adolescents seeking information on the subject7.

The aim of our study was to assess the impact in the short and long term (6 months after) of an educational intervention on the knowledge and attitude of testicular self-examination in male adolescents.

Material and methodsThe study was conducted between January 2019 and January 2020 in the Department of Adolescent Care of a tertiary care children’s hospital. We consecutively recruited all adolescents visiting the outpatient clinic of the Department of adolescent care for the initial evaluation or for follow-up. The sampling method was nonprobabilistic. It was a quasi-experimental, pre-test post-test study in a sample of male adolescents. We excluded patients who refused to participate, who did not know how to read or write, who did not fill out the questionnaire completely or who did not undergo the educational intervention. We interviewed participants to collect data on their age, school enrolment, occupation and province of residence.

Educational interventionAn informational talk was given, explaining the anatomy of the male reproductive system and illustrating the steps involved in performing a testicular self-examination, in addition to its usefulness, importance, how and how often to perform it, warning signs that merit requesting a medical evaluation and risk factors for development of testicular cancer. We distributed flyers to the adolescents and hung posters in the outpatient clinic that remained in place for the duration of the study (8 months). The talk was given by a paediatrician with specialised training on adolescent medicine, and lasted approximately 20min. After the talk, the paediatrician answered questions posed by the participants.

Questionnaire to measure the results of the interventionWe assessed knowledge and attitudes on testicular self-examination by means of a questionnaire previously used in the United Kingdom in men aged 18–45 years16,19.

A company specialised in medical writing (LATAM-ENAGO Academy) did the back and forward translation of the items of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire comprised 16 items, with answers given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The questionnaire assessed knowledge and attitudes on testicular cancer and self-examination. The attitudes section was divided into components of awareness, behavioural intent and behaviour:

KnowledgeThe knowledge section assessed knowledge of signs and symptoms of testicular cancer. This included risk factors for the presence of testicular cancer and the early detection of testicular abnormalities. All the information for the items of the questionnaire was obtained from the American Cancer Society6 (items 11–16, with the level of knowledge considered good with a score of 24–30, fair with a score of 18–23 and poor with a score ≤ 17). The knowledge scale has shown adequate reliability (validation of translation: α=0.81).

AttitudesWe evaluated attitudes through 3 components: awareness, behavioural intent and behaviour.

Awareness was assessed in items 1–4, and rated good for scores of 16–20 points, fair for scores of 12–15 points and poor for scores of 11 or fewer points. The awareness subscale has shown adequate reliability (validation of translation: α=0.77).

Behavioural intent was assessed in items 5 and 6, and rated good for scores of 8–10 pints, fair for scores of 6–7 points and poor for scores of 5 or fewer points. The behavioural intent subscale has shown adequate reliability (validation of translation: α=0.84).

Self-reported behaviour related to testicular cancer was assessed with items 7–10, and rated good for scores of 16–20 points, fair for scores of 12–15 points and poor for scores of 11 or fewer points. The behaviour subscale has shown adequate reliability (validation of translation: α=0.81).

The knowledge and attitudes questionnaire was administered to male adolescents aged 10–18 years managed in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Adolescent Care of the Hospital Infantil de México between January and May 2019. In the first validation round, it was administered to 20 male adolescents; adjustments were made based on the results, and second and third validation rounds were performed with administration to 20 adolescents in each. At the end of the third round, the reliability of the questionnaire was adequate, with a Cronbach α greater than 0.80.

Short-term impactOnce the questionnaire had been validated, we implemented the group educational intervention in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Adolescent Care of the Hospital Infantil de México from June to August 2019, administering the questionnaire before and after the intervention.

Long-term impact (6 months after)Six months after the initial educational intervention, we contacted the adolescents to invite them to attend a second group-based educational talk in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Adolescent Care of the Hospital Infantil de México between December 2019 and February 2020. The questionnaire was administered again before (third time) and after (fourth time) the second talk.

The research protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of the hospital under file R-2017-21. The parents of participants signed their informed consent, and the adolescents themselves their informed assent, in adherence with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisFor quantitative data, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test, and since we found that the data did not follow a normal distribution, we summarised them with the median, minimum and maximum values.

To assess differences between questionnaire scores before and after the educational intervention and 6 months later, we used the Wilcoxon sign test for repeated measures.

To assess differences in the proportions of participants that exhibited good attitudes and good knowledge regarding testicular self-examination before and after the intervention, we used the Fisher exact test.

We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

The analyses were performed with the software STATA, version 12.

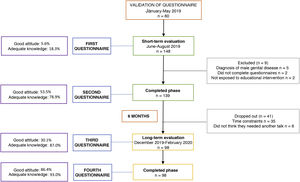

ResultsShort-term impact of the educational interventionWe identified 148 patients as potential candidates, of who only 139 were included; 5 were excluded due to an established diagnosis of male genital disease, 2 due to incomplete data in the questionnaire and 2 due to missing the educational intervention due to time constraints (Fig. 1).

In the resulting sample, the median age was 14 years; most participants were currently enrolled in secondary education (Table 1).

Characteristics of male adolescents who completed the second phase of the study.

| Short term | Long term | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=138 | n=98 | |||

| n (%) | P | |||

| Agea | 14 (10−18%) | 14 (10−18%) | ||

| Education cycle | Primary | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (3.33%) | 0.050 |

| Secondary | 48 (67.6%) | 24 (80%) | ||

| Preparatory | 22 (31%) | 5 (16.66%) | ||

| Occupation | Student | 68 (95.8%) | 27 (90%) | 0.039 |

| None | 3 (4.2%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| Residence | Mexico City | 63 (88.7%) | 29 (96.7%) | 0.330 |

| Province | 8 (11.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

Table 2 shows that when it came to attitudes (further divided into awareness, intent and behaviour), participants generally exhibited a poor attitude toward testicular self-examination in the pre-intervention test (median scale score of 29), and only 5.6% (n=4) exhibited a good attitude, whereas when it came to knowledge about testicular self-examination, they generally had fair knowledge (median scale score of 21), and 18.3% (n=13) had adequate knowledge at baseline (Table 2).

Scores on attitudes and knowledge about testicular self-examination assessed in the 138 adolescents before and after the delivery of the intervention in phase 2 of the study (short term).

| Pre-intervention | Total | Post-intervention | Total | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | ||||||

| Awareness | I have been exposed to information regarding testicular cancer | 3 (1−5) | 11 (4−20) | 5 (1−5) | 18 (4−20) | 0.000 |

| I know the warning signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 2 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| I know where to go to find accurate information about testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| I know how to perform a self-exam for testicular cancer to check that everything is fine | 3 (1−5) | 5 (1−5) | ||||

| Intent | I am ready to perform a self-exam for testicular cancer in the next month | 3 (1−5) | 7 (2−10) | 5 (1−5) | 9 (2−10) | 0.000 |

| I plan to talk with my doctor about the risks, signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| Behaviour | I perform a testicular self-exam every month | 2 (1−5) | 11 (4−20) | 3 (1−5) | 13 (4−20) | 0.000 |

| I have discussed testicular cancer with my doctor | 2 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| I search for information on testicular cancer on the Internet | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| I have discussed testicular cancer with friends or family | 2 (1−5) | 2 (1−5) | ||||

| Assessment of provided information-knowledge | Testicular cancer mainly occurs in young and middle-aged men | 4 (1−5) | 21 (6−28) | 5 (1−5) | 27 (6−30) | 0.000 |

| Cryptorchidism and a family history of testicular cancer are among the risk factors for testicular cancer | 3 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| Testicular cancer can be detected early through testicular self-examination | 4 (1−5) | 5 (1−5) | ||||

| The best time to perform a testicular self-exam is during or after a warm bath or shower, when the skin of the scrotum is relaxed | 4 (1−5) | 5 (1−5) | ||||

| It is normal for one testicle to be slightly larger or hang lower than the other | 3 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| A lump or swelling in the testicle, pain or a feeling of heaviness are some of the signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 3 (1−5) | 5 (1−5) | ||||

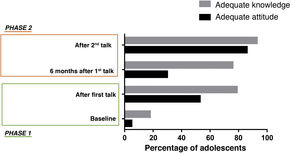

After the intervention, there was improvement in the attitude score (29 vs 40; P< 0.001) and the knowledge score (21 vs 27; P< 0.000), in addition to an increased proportion of adolescents with a good attitude (5.6% vs 53.5%; P= 0.02) and adequate knowledge (18.3% vs 78.9%; P= 0.02) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Long-term impact of the educational intervention (6 months after)In the third phase, there were only 98 participants (out of the 139 that completed the second phase); 35 patients reported not being able attend the following talk due to school, and 6 patients refused on the grounds that they did not need a second talk, as a single one was sufficient for them (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of the group of 98 patients who participated in the assessment of the long-term impact of the intervention (phase 3) were a median age of 14 years, with an age range of 10–18 years; with 18 patients (60%) residing in Mexico City and the rest outside the city limits (Table 1).

The results of the third test (6 months after the initial talk) evinced a decreasing trend in the awareness and behaviour scores compared to the second test, although it was not statistically significant (Table 3). However, when we compared the proportion of adolescents with a good attitude score in the post-test after the initial educational intervention (talk) compared to the test performed before the second talk 6 months after the first (third test), we found that the proportion had decreased (53.5% vs 30.1%; P= 0.02) (Fig. 2).

Scores on attitudes and knowledge about testicular self-examination assessed in the 98 adolescents before and after the delivery of the intervention in phase 3 of the study (long term).

| Score after first talk | Total | Score 6 months after first talk | Total | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | ||||||

| Awareness | I have been exposed to information regarding testicular cancer | 5 (1−5) | 17 (4−20) | 5 (2−5) | 16 (6−20) | 0.07 |

| I know the warning signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (2−5) | ||||

| I know where to go to find accurate information about testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| I know how to perform a self-exam for testicular cancer to check that everything is fine | 5 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| Intent | I am ready to perform a self-exam for testicular cancer in the next month | 5 (1−5) | 8 (2−10) | 4 (1−5) | 9 (2−10) | 0.81 |

| I plan to talk with my doctor about the risks, signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| Behaviour | I perform a testicular self-exam every month | 3 (1−5) | 13 (4−20) | 4 (1−5) | 12 (4−19) | 0.52 |

| I have discussed testicular cancer with my doctor | 4 (1−5) | 3 (1−5) | ||||

| I search for information on testicular cancer on the Internet | 4 (1−5) | 3 (1−5) | ||||

| I have discussed testicular cancer with friends or family | 2 (1−5) | 2 (1−5) | ||||

| Assessment of provided information-knowledge | Testicular cancer mainly occurs in young and middle-aged men | 5 (1−5) | 25 (6−30) | 2 (1−5) | 25 (6−30) | 0.75 |

| Cryptorchidism and a family history of testicular cancer are among the risk factors for testicular cancer | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| Testicular cancer can be detected early through testicular self-examination | 5 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| The best time to perform a testicular self-exam is during or after a warm bath or shower, when the skin of the scrotum is relaxed | 5 (1−5) | 5 (1−5) | ||||

| It is normal for one testicle to be slightly larger or hang lower than the other | 4 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

| A lump or swelling in the testicle, pain or a feeling of heaviness are some of the signs and symptoms of testicular cancer | 5 (1−5) | 4 (1−5) | ||||

After the second intervention, we found a substantial increase in the proportion of adolescents with a good attitude toward testicular self-exploration (second intervention: 30.1% in pre-test vs 86.4% in post-test; P= 0.001), and this proportion was also greater compared to the proportion after the first talk (test after first talk, 53.5% vs test after second talk, 86.4%; P= 0.003) (Fig. 2).

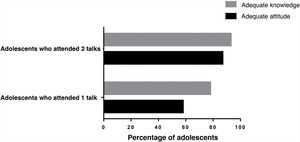

On one hand, when we compared the proportion of adolescents with adequate knowledge among the adolescents who attended 1 talk and those who attended 2 talks, we found that the difference was not significant (1 talk, 87.0% vs 2 talks, 93.0%; P= 0.671), but on the other, when we compared the proportion with a good attitude, we found a significantly greater proportion in the group of adolescents that attended 2 talks (1 talk, 58.0% vs 2 talks, 78.0%; P= 0.009) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionMain findingsOverall, we found a very low proportion of adolescents with a favourable attitude (5.6%) and adequate knowledge (18.3%) about testicular self-examination.

The delivery of an educational talk on testicular self-examination to male adolescents significantly improved knowledge on the subject, however, we found that improvements in favourable attitudes waned significantly 6 months after the initial talk.

Although our goal was to assess the impact of an educational intervention on testicular self-examination in adolescents, it is important to mention that at baseline, we found a low proportion of adolescents with favourable attitudes and adequate knowledge regarding self-examination, in agreement with the findings of other studies conducted in male adolescents and young adults3,8,10,11, which reflects how little this subject is discussed in the population and the scarce efforts made to promote routine self-examination and awareness of the warning signs of testicular disease.

In our study, delivery of the educational intervention was associated with a substantial improvement in knowledge on the subject, with short-term improvements in attitude and knowledge of 53.5% and 78.9%, respectively, evincing that the main problem is the lack of dissemination on testicular self-examination, which contributes to inadequate knowledge and behaviour. Along the same lines, Wanzer et al. carried out a study in New York through a comprehensive testicular cancer and self-examination campaign in 220 college students who completed measures before and after the campaigns and in a control group of 52 students who were not exposed to the campaign messages. The study found an overall improvement in knowledge and awareness. The campaign included similar strategies, delivering information through flyers, posters, shower cards and online platforms, and the authors found that the knowledge on testicular cancer and self-examination of the students improved by 12% after the campaign, and that exposure to specific materials (shower cards) was associated with a self-reported improvement in awareness compared to students not exposed to them, with a 5% change16.

Several past studies have evinced that informational talks substantially improve knowledge on testicular self-examination in male adolescents and young adults, with improvements ranging from 10.3% to 68.3%3,10,14. This is consistent with our results, as we found a statistically significant improvement in awareness and behaviour, corresponding to a 53.5% change, in the short term.

When it comes to the factors that may have an impact on testicular self-examination in adolescents, Shepherd and Watt identified a collection of emotional factors that could promote or discourage self-examination (anxiety, shame, anticipated regret and relief), evincing that these social-cognitive and emotional factors could have a negative effect on the improvement of awareness and behaviour of 10%18. Although we did not assess factors associated with the promotion or deterrence of testicular self-examination, we found that adolescents in a higher educational level were less likely to return for a second educational intervention.

As regards the educational intervention, the study conducted in New York showed that reinforcement at 2 different times with multiple informational strategies and the use of pre-a and post-intervention measures significantly increased knowledge acquisition between baseline and the end of the intervention16; this was also the case in our study, where we found that the proportion of adolescents with adequate knowledge was maintained in the short and long term (78.9% and 76.6%).

We found that maintaining good attitudes (53.5%) required reinforcement of what had been learned (6 months), as a second educational intervention improved behavioural intent, which had not changed with a single talk, and promoted adherence of adolescents to testicular self-examination, while the proportion of good knowledge of self-examination remained constant (78.9% vs 76.0%) 6 months after receiving the informational talk. This was similar to the findings of a study by Roy and Casson in Northern Ireland, which included 150 men aged 18–45 years, seeking to determine the level of awareness, knowledge and attitudes toward testicular cancer and self-examination through an educational intervention, reporting a 50% decline in attitude over time, evincing the need of reinforcement, however, acquired knowledge was maintained in 70% after 6 months9.

Overall, the findings of our study, supported by the previous literature, clearly evinced the need of specific efforts to disseminate information on testicular cancer targeting youth in order to increase the efficacy of testicular self-examination11.

We propose delivering this type of educational intervention in the school setting, which students have to attend, with a minimum of 1 talk sufficing to substantially improve attitudes and knowledge; however, since attitudes decline over time, reinforcement of the educational intervention at least every 6 months is required to maintain good attitudes.

ConclusionAfter delivering an educational intervention in a paediatric hospital, we conclude that there was substantial improvement in the proportion of adolescents with a good attitude (5.6% vs 53.5%) and adequate knowledge (18.3% vs 78.9%) after the intervention in the short term (testing before and after the intervention).

We found that the proportion of adolescents with a good attitude decreased when we assessed the results of the intervention 6 months after its delivery (53.5% vs 30.5%), while the proportion of adolescents with adequate knowledge was maintained in the short and long term (78.9% vs 76.6%).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.