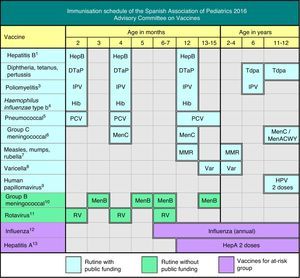

The Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics (CAV-AEP) annually publishes the immunisation schedule which, in our opinion, estimates optimal for children resident in Spain, considering available evidence on current vaccines. We acknowledge the effort of the Ministry of Health during the last year in order to optimise the funded unified Spanish vaccination schedule, with the recent inclusion of pneumococcal and varicella vaccination in early infancy.

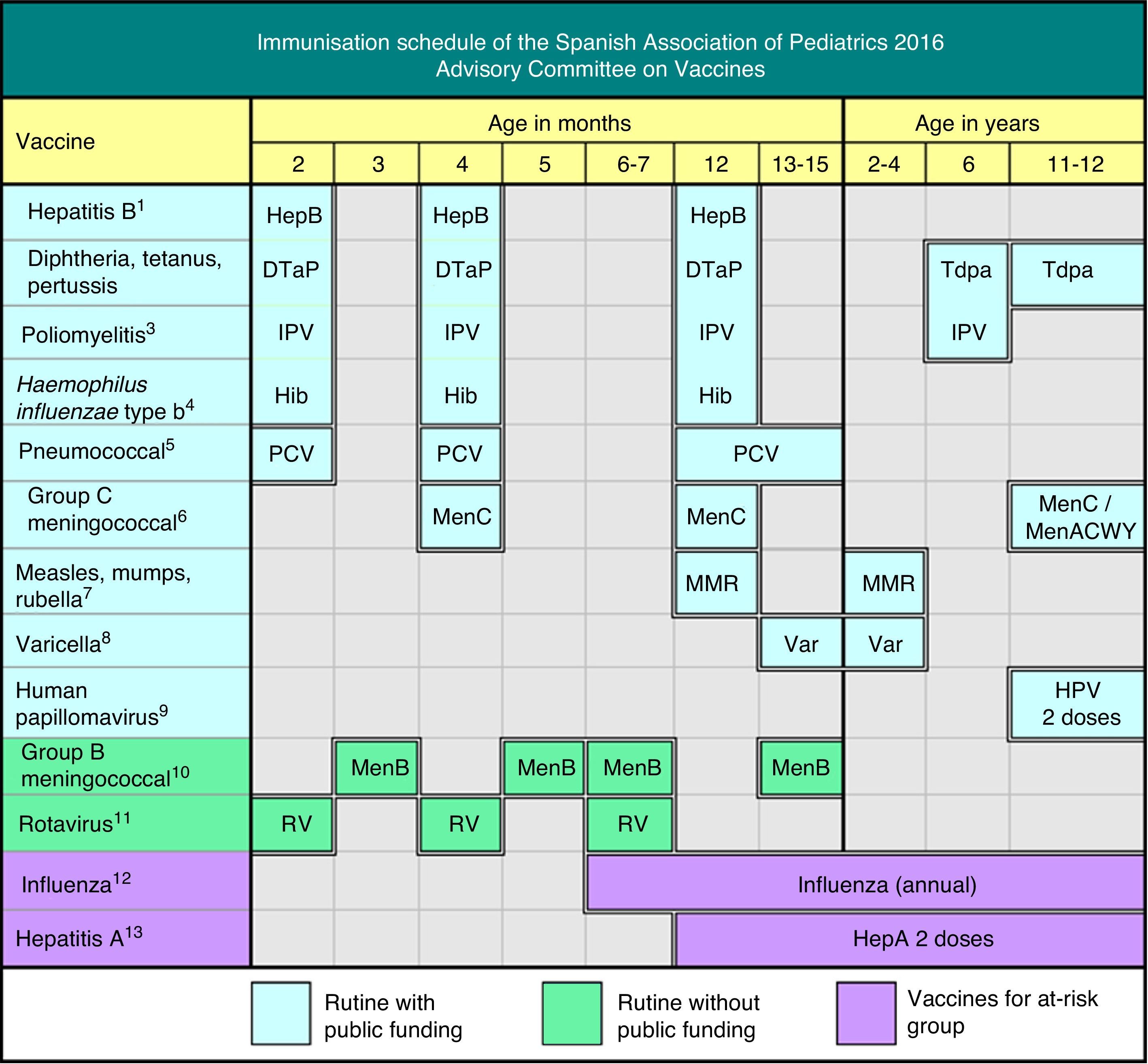

Regarding the funded vaccines included in the official unified immunisation schedule, taking into account available data, CAV-AEP recommends 2+1 strategy (2, 4 and 12 months) with hexavalent (DTPa-IPV-Hib-HB) vaccines and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Administration of Tdap and poliomyelitis booster dose at the age of 6 is recommended, as well as Tdap vaccine for adolescents and pregnant women, between 27 and 36 weeks gestation.

The two-dose scheme should be used for MMR (12 months and 2–4 years) and varicella (15 months and 2–4 years).

Coverage of human papillomavirus vaccination in girls aged 11–12 with a two dose scheme (0, 6 months) should be improved. Information for male adolescents about potential beneficial effects of this immunisation should be provided as well.

Regarding recommended unfunded immunisations, CAV-AEP recommends the administration of meningococcal B vaccine, due to the current availability in Spanish communitary pharmacies, with a 3+1 scheme (3, 5, 7 and 13–15 months). CAV-AEP requests the incorporation of this vaccine in the funded unified schedule. Vaccination against rotavirus is recommended in all infants.

Annual influenza immunisation and vaccination against hepatitis A are indicated in population groups considered at risk.

El CAV-AEP publica anualmente el calendario de vacunaciones que estima idóneo para los niños residentes en España, teniendo en cuenta la evidencia disponible sobre las vacunas. Reconocemos el esfuerzo del Ministerio de Sanidad, en el último año, por optimizar el calendario común, con la inclusión de la vacunación frente al neumococo y la varicela en la primera infancia.

En cuanto a las vacunas financiadas incluidas en el calendario común, con los datos disponibles actualmente, y dada la falta de disponibilidad del componente de tosferina, se recomienda emplear esquemas 2+1 (2, 4 y 12 meses) con las vacunas hexavalentes y con la antineumocócica conjugada 13-valente.

Se aconseja un refuerzo de Tdpa a los 6 años, junto con una dosis de polio, así como vacunación con Tdpa en adolescentes y embarazadas, entre las semanas 27–36.

Se emplearán esquemas de 2 dosis para triple vírica (12 meses y 2–4 años) y varicela (15 meses y 2–4 años).

Se deben incrementar las coberturas frente al papilomavirus en niñas de 11–12 años con 2 dosis (0–6 meses), así como informar a los varones de los beneficios potenciales de la vacunación.

Respecto a las vacunas recomendadas no financiadas, dada su disponibilidad en las farmacias comunitarias, se recomienda la vacuna frente al meningococo B, con esquema 3+1 (3, 5, 7 y 13–15 meses), solicitando su entrada en el calendario. Es recomendable vacunar a todos los lactantes frente al rotavirus.

La vacunación antigripal anual y la inmunización frente a la hepatitis A están indicadas en grupos de riesgo.

The Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics (CAV-AEP) updates the immunisation schedule every year, taking into account current evidence to propose the recommendations on vaccination that it considers most appropriate for children residing in Spain.

This year, major changes have been made to the recommendations of this Committee, as can be seen in Fig. 1, partly due to new developments that have taken place in recent months, such as the inclusion of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and the vaccine against varicella in the official immunisation schedules in 2015 and 2016.1 The Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality (Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [MSSSI]) has taken into consideration these two important demands of the CAV-AEP, to the great delight of paediatricians and society. It has also announced the distribution of the vaccine against varicella in community pharmacies, and the long-awaited arrival of the meningococcal B vaccine, also demanded by paediatricians.

Due to the short supply of the pertussis vaccine, and for the purpose of optimising the immunisation schedule, adapting it to current epidemiological conditions, increasing its efficacy and converging towards the homogenisation of vaccination schedules in Europe, the CAV-AEP has made various modifications, implementing 2+1 schedules with hexavalent vaccines.

Ideally, scientific societies would be taken into account in the decision-making process, and the autonomous communities (ACs) and the MSSSI would make a greater collective effort to fund a more comprehensive routine immunisation schedule for Spanish children. Alternative systems should be set up to assist families in paying for vaccines that are not funded by the state, as is done in other countries in the European Union and in Spain in relation to commonly used medications.

Due to the space restrictions of this document, we recommend the reading of the expanded overview of these recommendations available at our website, www.vacunasaep.org.

In 2015, the case of diphtheria in Olot and the two cases of poliomyelitis in Ukraine underscored the need to continue vaccinating every child, striving to maintain high vaccination coverage rates and to persuade parents that refuse vaccination.

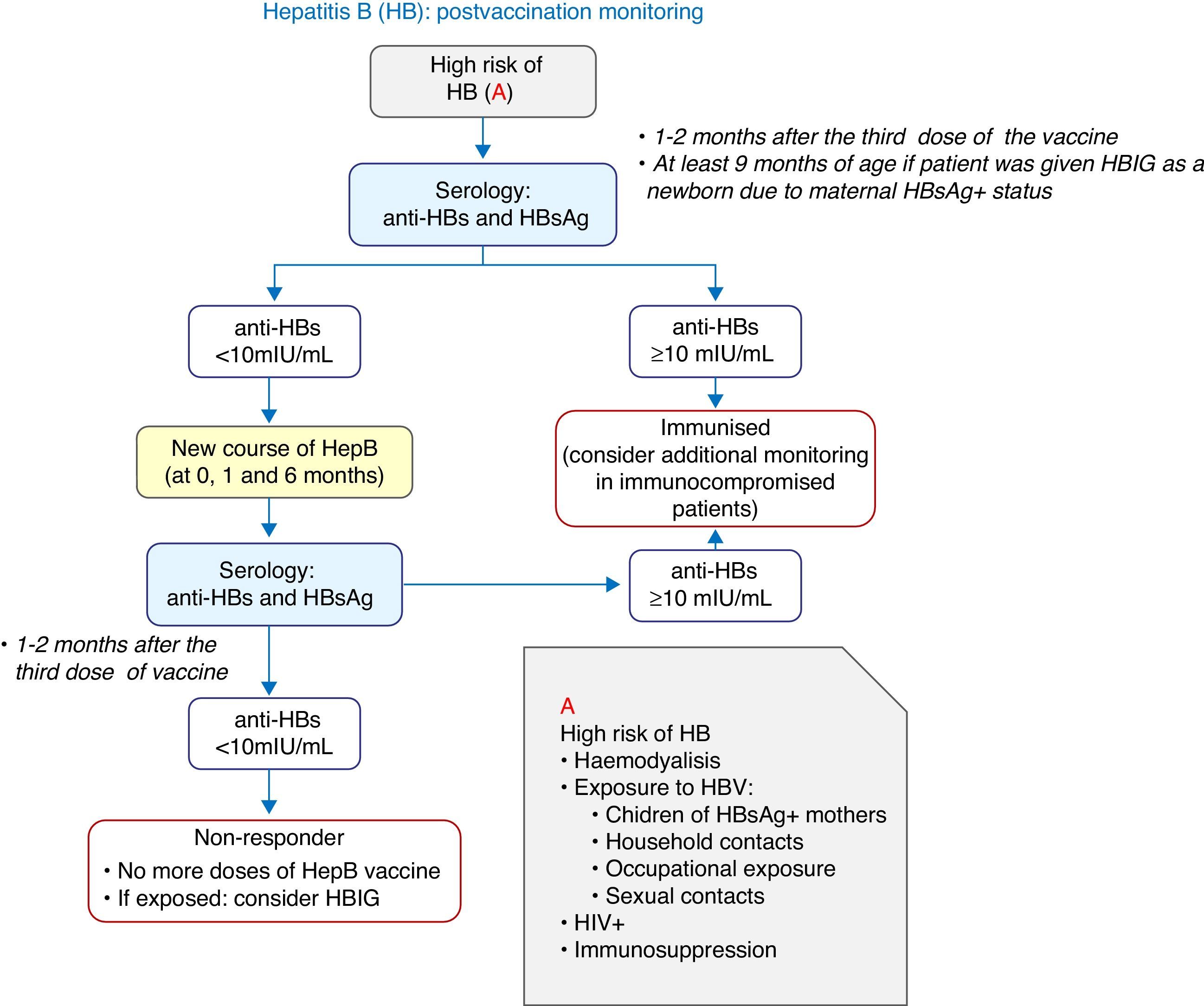

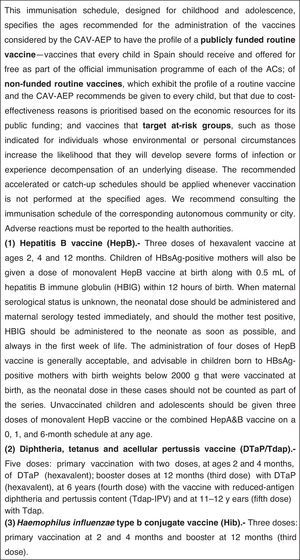

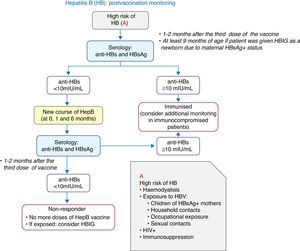

Vaccination against hepatitis B2016 recommendation: We recommend the vaccination of infants with three doses of hexavalent vaccine at 2, 4 and 12 months of age. Previously unvaccinated older children and adolescents will receive 3 doses of the monovalent vaccine alone or combined with the hepatitis A vaccine at 0, 1 and 6 months.

In Spain, the annual incidence of hepatitis B (HBV) rose slightly in 2013 compared to 2012 (1.53 and 1.27 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively).2 In 2015, the first dose was given at birth in more than half of the ACs, a schedule that should be maintained if it is believed that there is suboptimal screening of pregnant women.

There is evidence that delaying the age at which the last dose of the vaccine is administered and increasing the interval between doses can improve immunological memory, offering greater protection against HBV in adults,3 and this can be achieved with a 2+1 schedule.

The vaccination of newborns is always to be performed with the monovalent vaccine, which will be prescribed to children born to mothers that are HBsAg-positive or of unknown serological status. Babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers should also be given anti-hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG), preferably in the first 12h of life.

Four-dose schedules may be administered in infants that were vaccinated as newborns.

Fig. 2 presents a decision algorithm for the management of at-risk patients.

Vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis and Haemophilus influenzae type b2016 recommendation: We recommend primary vaccination with the hexavalent DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine at 2, 4 and 6 months. The first dose can be given earlier at 6 weeks post birth. A booster dose, also of the hexavalent vaccine, should be administered at 12 months of age (2+1 schedule), with subsequent boosters with the Tdap-IPV vaccine at age 6 years and with the Tdap vaccine at age 11–12 years. Vaccination with a dose of Tdap is recommended in all pregnant women between weeks 27 and 36 of gestation, and in all household members that will be in contact with the newborn (especially any postpartum mothers that were not vaccinated during pregnancy).

The incidence of pertussis has increased worldwide,4 with infants suffering the highest burdens and most severe forms of disease. Preventive strategies must prioritise the protection of this group. Vaccination of women with the Tdap during the third trimester of gestation is safe and efficacious, and it is the most effective and efficient method for preventing pertussis in infants.5

The 2+1 primary vaccination and booster schedule is used in many European countries. We believe that this schedule, which is both safe and immunogenic, optimises the available doses of vaccine, as one less dose is used for primary vaccination.6

We uphold the recommendation of the WHO (2014) of administering one dose of OPV or IPV to travellers residing or meaning to stay for more than 4 weeks in countries affected by polio. This dose must be received within 4 weeks to 12 months of travel. The recent occurrence of two cases of poliomyelitis in unvaccinated children in Ukraine caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 underscores the need to maintain high coverage rates of vaccination against polio. The 2+1 primary vaccination series with hexavalent vaccine calls for the administration of a polio booster at age 4–6 years with the Tdap-IPV vaccine, as many countries have been doing. Spain is one of the few European countries that do not administer this booster dose after age 2 years.

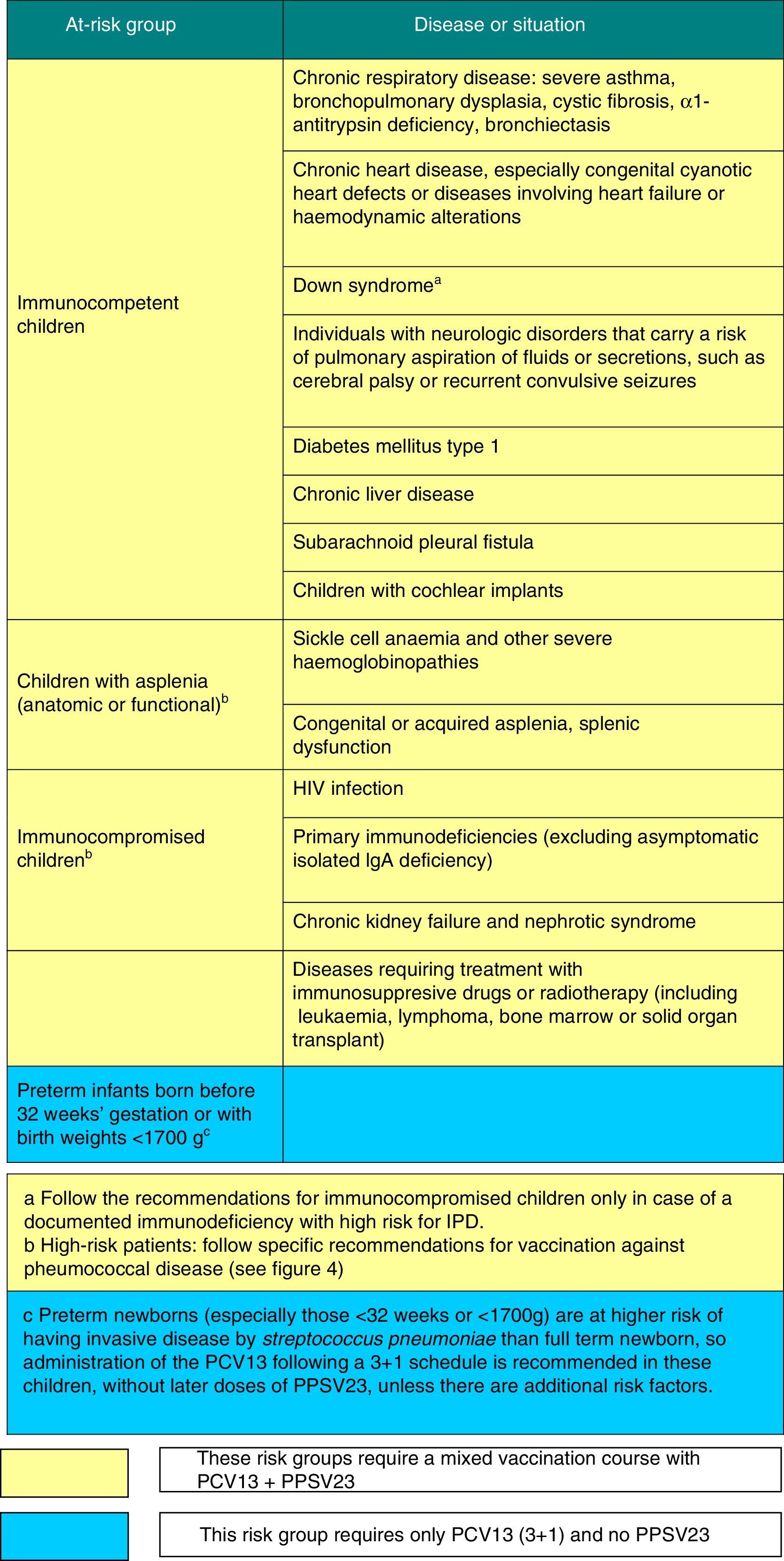

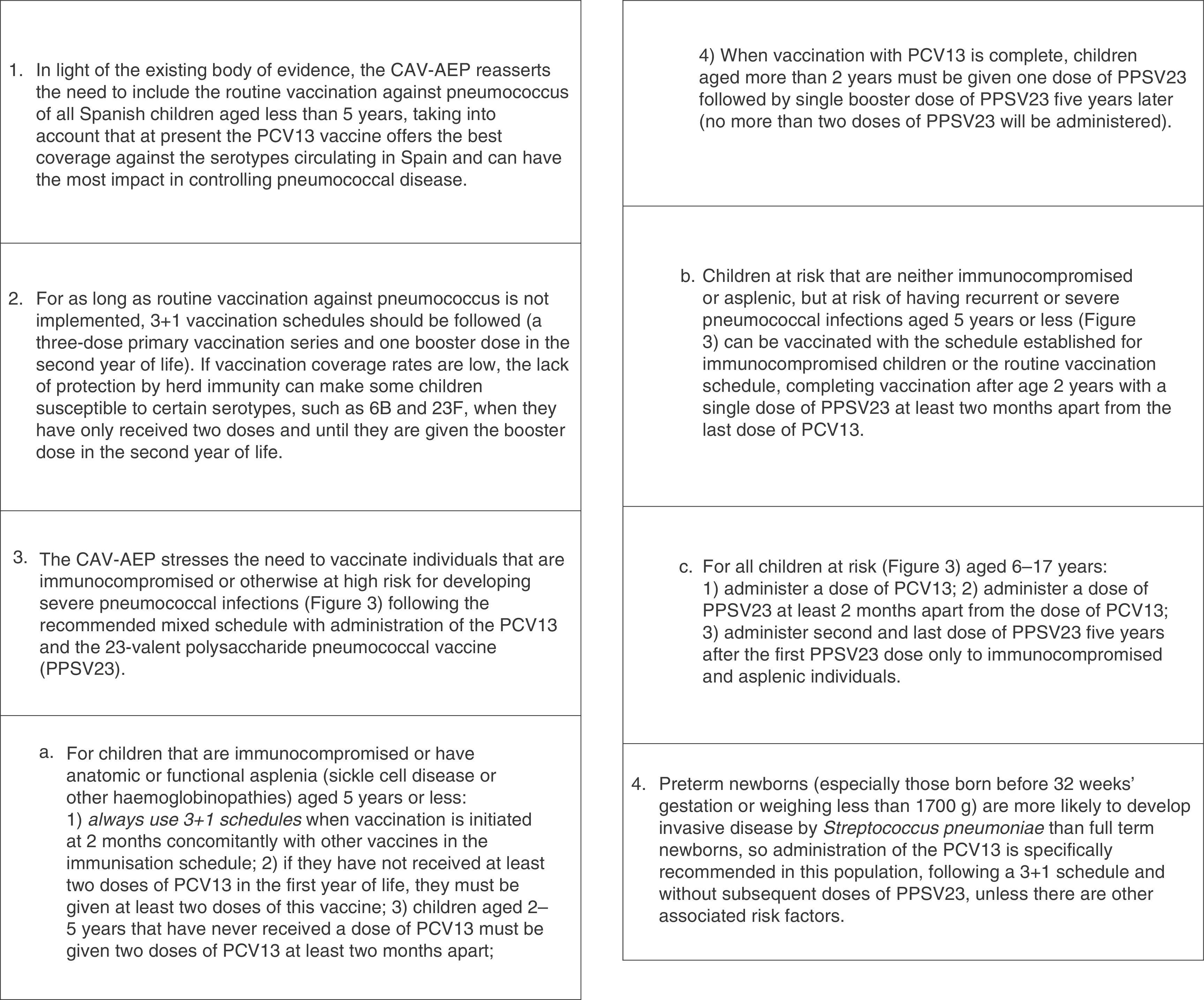

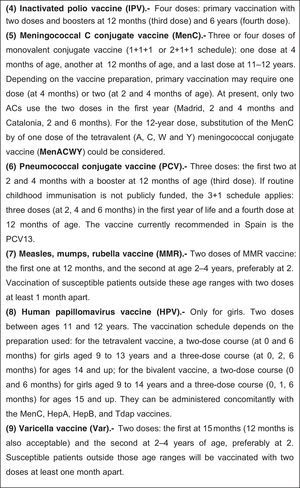

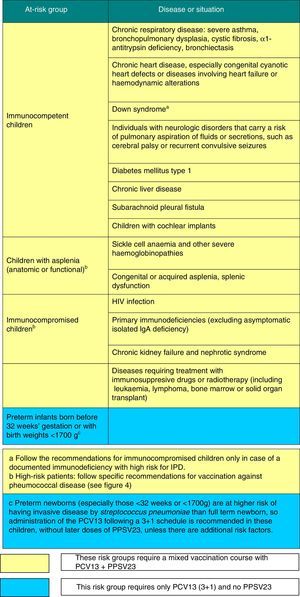

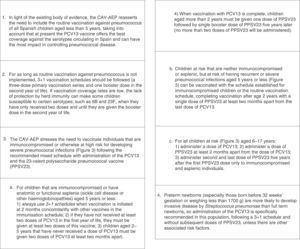

Vaccination against pneumococcal disease2016 recommendation: Vaccination against pneumococcal disease is recommended for all children younger than 5 years and children that are immunocompromised or otherwise at risk at any age. Routine vaccination can be performed starting in infancy with a 2+1 series (at 2, 4, 12–15 months), but in the absence of routine vaccination, the series should follow a 3+1 schedule. We recommend the use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) based on epidemiological data for Spain, its demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the rate of all forms of noninvasive disease and its capacity to induce herd immunity in all age groups.

The evidence of the capacity of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (10-valent [PCV10] and PCV13) to cause a marked reduction in the rate of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) continues to grow.7,8 These two vaccines also have a significant impact on noninvasive pneumococcal disease, having led to a reduction in the number of hospitalisations for pneumonia caused by pneumococcus or of other aetiologies in vaccinated as well as unvaccinated individuals.9

The PCV13 significantly reduces nasopharyngeal colonisation by vaccine serotypes, including 19A.10 It is almost certain that this fact accounts for the marked reduction brought by this vaccine on noninvasive forms of pneumococcal disease such as pneumonia11,12 and acute otitis media,13 as well as for the herd immunity against IPD and pneumonia in both children and adults.

There are fewer studies on the impact of PCV10 on nasopharyngeal colonisation and noninvasive forms of pneumococcal disease. The PCV10 produces a considerable reduction of hospitalisations due to pneumonia,9 although this reduction is not as significant as the one achieved by the PCV13.11,12 This may be due to the nonexistent impact of the PCV10 on the rate of nasopharyngeal colonisation by serotype 19A,14 which in fact increases after vaccination with the PCV10.15 Moreover, given the importance of nasopharyngeal colonisation as regards herd immunity, it is unlikely that the PCV10 with achieve this protection against serotype 19A, as illustrated by the experience in Finland, where the number of cases of PID by this serotype has increased significantly in unvaccinated individuals and overall in the entire population.16

Figs. 3 and 4 show the groups at risk for pneumococcal disease and the recommendations for vaccination against pneumococcus.

2016 recommendation: We recommend three to four doses of the monovalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (series of 1 [or 2]+1+1), with the following schedule: a first dose at 4 months (or two doses at 2 and 4 months, depending on the vaccine used), another at 12 months, and a last one at 12 years of age. In adolescents, this last dose may be replaced by one dose of tetravalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

There is extensive evidence on the effectiveness of this vaccine.17 The rate of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) by serogroup C remained very low in Spain during the 2012–2013 season (0.06 cases per 100,000 inhabitants). The incidence of meningococcal disease by other serogroups (W, Y and A) continues to be low in Spain at less than 5%. The availability of tetravalent conjugate vaccines (Menveo® and Nimenrix®),18 reserved for vaccination of travellers to endemic regions, provides an ideal alternative for booster doses in adolescence, given the increased frequency of travel in this age group. The use of this vaccine is recommended at any age, especially in immunocompromised patients at high risk of IMD (complement deficiency, congenital or functional asplenia), for whom the CDC recommends revaccination every 5 years.19

Vaccination against measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)2016 recommendation: We recommend that a first dose of MMR vaccine be given at 12 months of age, with a second dose given between 2 and 4 years of age, preferably at 2, for the early remediation of any potential primary vaccine failures.

Between July 2014 and June 2015, the number of reported cases of measles in the WHO European Region decreased, although it continued to be unacceptably high; as did the number of rubella cases and outbreaks of mumps. The incidence of these diseases in Spain is low, but nevertheless shows the same trends.20 It is essential that high coverage rates and thorough surveillance are maintained if we are to eradicate these diseases. The administration at 12 months of a single dose of vaccine achieves seroconversion rates of 95% and higher for all three viruses, rates that approximate 100% after administration of the second dose.

Vaccination against varicella2016 recommendation: It is recommended that all children be vaccinated against varicella with two doses: one at 15 months and another at 2–4 years of age. It is also recommended that a two-dose catch up vaccination be done in children and adolescents that have not had the disease and are unvaccinated (or that the series is completed in those who have only received one dose in the past).

The MSSSI has approved the inclusion of vaccination against varicella with a two-dose schedule (at 12–15 months and 3–4 years) starting in 2016.21 The two vaccines currently available (Varilrix® and Varivax®)18 have demonstrated high effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cases and complications, both in vaccinated and the unvaccinated individuals,22,23 while exhibiting an excellent safety profile.24

Varicella vaccination is being rigorously monitored in Europe, where its potential benefits and cost-effectiveness are under debate. The impact of the disease and the need to achieve high vaccination coverage rates with two doses are critical aspects that need to be researched.24

After nearly 20 years of vaccination in the United States, there has been no evidence of a shift in the age of disease.23 There had been an increase in the incidence of herpes zoster (HZ) prior to the introduction of childhood vaccination against varicella,25 and several studies have concluded that there is no evidence of vaccination having any influence on the incidence of HZ,25,26 although its incidence is lower in vaccinated children than in children with a history of natural varicella.27 Childhood vaccination against varicella can only be considered cost-effective if there is evidence that it is not associated with an increase in the incidence of HZ in the general population, and especially in individuals aged more than 50 years, while the potential impact of vaccinating the latter against HZ is being evaluated.24

The optimal interval between doses and the duration of the protection conferred by vaccination remain to be determined, and a rigorous epidemiologic surveillance is essential to this end.24

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV)2016 CAV-AEP recommendation: Routine vaccination against HPV is recommended for all girls aged 11–12 years as a means to prevent cervical cancer and precancerous lesions in the female genital tract.

We believe that the optimal age for vaccination is 11–12 years. The 2015 recommendation of the MSSSI already incorporated the appeal of the CAV-AEP for advancing vaccination to age 12 years.1The currently approved dosage allows the administration of two doses in adolescents.18

The data that are currently available support both the efficacy and the effectiveness of universal vaccination programmes for the prevention of persistent infection by HPV, genital warts and preneoplasias, including high-grade lesions.28,29 We expect that data supporting the use of the vaccine for the prevention of cervical cancer and other cancers associated with HPV will soon follow.

Both vaccines have exhibited an adequate safety profile and a favourable benefit-risk ratio.29 Still, the average coverage rate in Spain has not grown past 75%. A greater effort is required of healthcare professionals to improve coverage.

The tetravalent vaccine has been approved for males18 and included in the official vaccination schedule of countries such as the United States, Canada, Austria, Switzerland and some regions in Italy. There is growing evidence on the role of HPV in the aetiopathogenesis of some types of cancer that affect both sexes, but especially those with a greater incidence in males, such as anal cancer and cancers of the head and neck.30 Information must be given and vaccination with the tetravalent vaccine considered for males aged 11–12 years.30

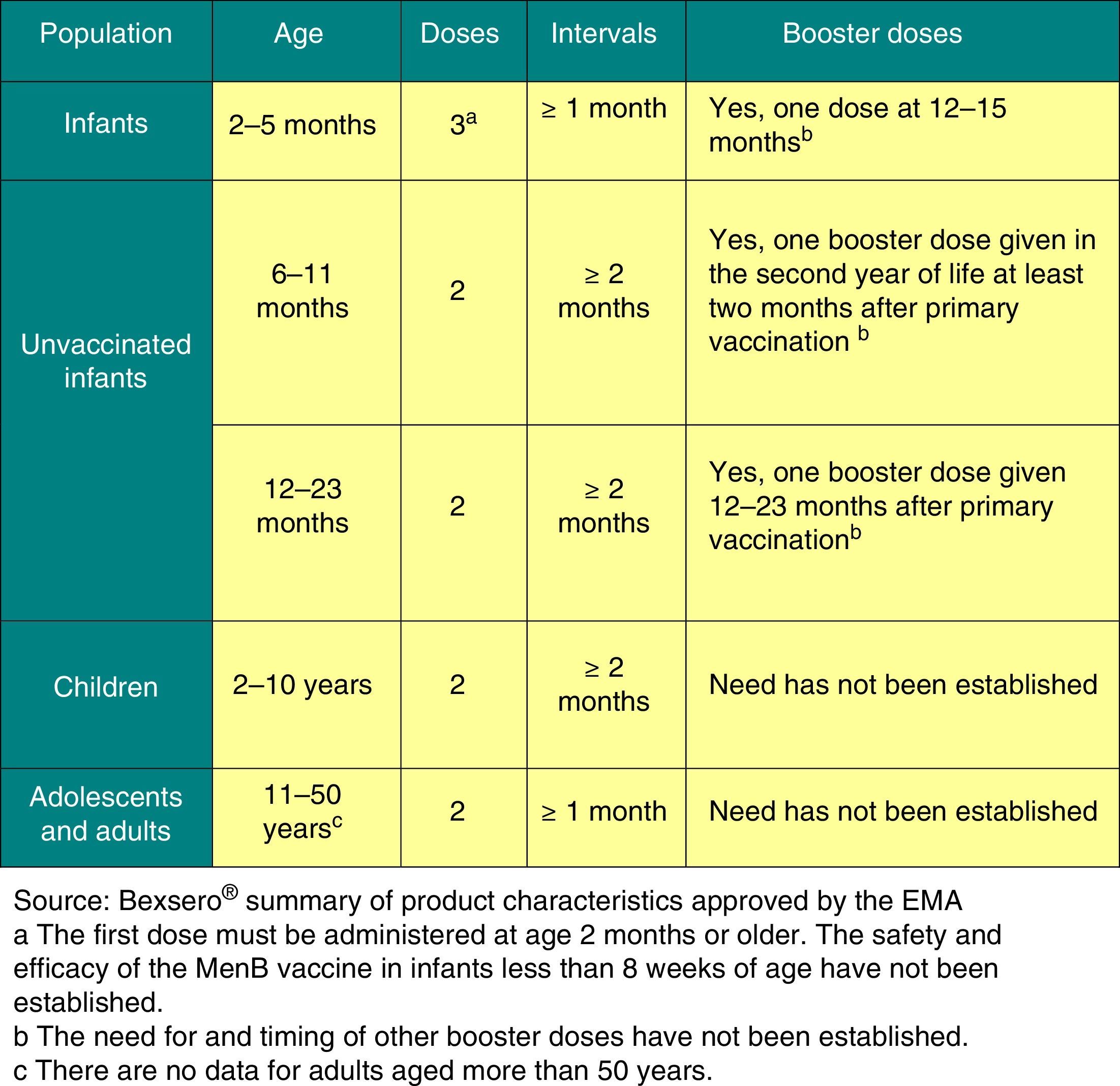

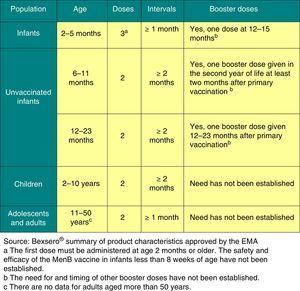

Vaccination against group B meningococcal disease2016 recommendation: The meningococcal B vaccine exhibits the profile of a routine vaccine to be administered to all children starting at 2 months of age.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that the only vaccine currently authorised in Europe for the prevention of group B IMD (Bexsero®) from 2 months of age is immunogenic and safe in infants, children, adolescent and adults, and induces immunologic memory. The decision of the United Kingdom (UK) to include it in its official schedule starting in September 1, 2015 has been particularly relevant, introducing the vaccine in infants with a 2+1 schedule (at 2, 4 and 12–13 months).31

Clinical trials have shown that Bexsero® may be administered concomitantly with the rest of the vaccines in the schedule, although this increases its reactogenicity. Administration of prophylactic paracetamol reduces the incidence of adverse events and does not affect the immunogenicity of this vaccine or any other vaccines in the routine schedule that are given concomitantly.Its compatibility with meningococcal C vaccines remains to be demonstrated.The AEMPS has authorised the distribution of this vaccine in community pharmacies starting on October 1, 2015.32Based on current data, we recommend33:

- 1.

Administration of Bexsero® without concomitant administration of other vaccines in the schedule, with doses at 3, 5 and 7 months or administered at least 2 weeks apart from other routine vaccines.

- 2.

This schedule would not require the routine use of prophylactic paracetamol.

- 3.

The booster dose should be given between 13 and 15 months of age to avoid an overlap with the meningococcal C vaccine.

2016 recommendation: Vaccination against rotavirus is an advisable and safe health intervention for all infants.

Since the introduction of the rotavirus (RV) vaccines in 2006, the morbidity and mortality of gastroenteritis due to RV infection in infants and young children has decreased considerably both in developing and developed countries.

Universal vaccination against rotavirus is recommended by the WHO for infants in every country of the world, and a significant decrease of morbidity and mortality caused by RV has been observed since the introduction of this vaccine in the official immunisation schedules of more than 77 countries (September 2015).

There is also evidence of a marked decline in the circulation of RV in European countries that have implemented routine vaccination, as can be observed in the UK after 2 years of universal vaccination.34

There has been a strict post-marketing surveillance, with a special focus on intussusception, for which a low risk has been observed (1–5 cases per 100,000 vaccinated children).35 It is important that the parents of children that are going to be vaccinated are informed of the benefits and risks of this vaccine, explaining the warning signs for intussusception so parents can act quickly and avoid the complications of a delayed diagnosis (it is important that vaccination is initiated before 12 weeks). The benefits of vaccination against rotavirus continue to significantly outweigh the hypothetical risks of intussusception.36

The pentavalent vaccine, RotaTeq®, continues to be the only one available in Spain. It is administered orally and can be given at the same time as other vaccines in the schedule.

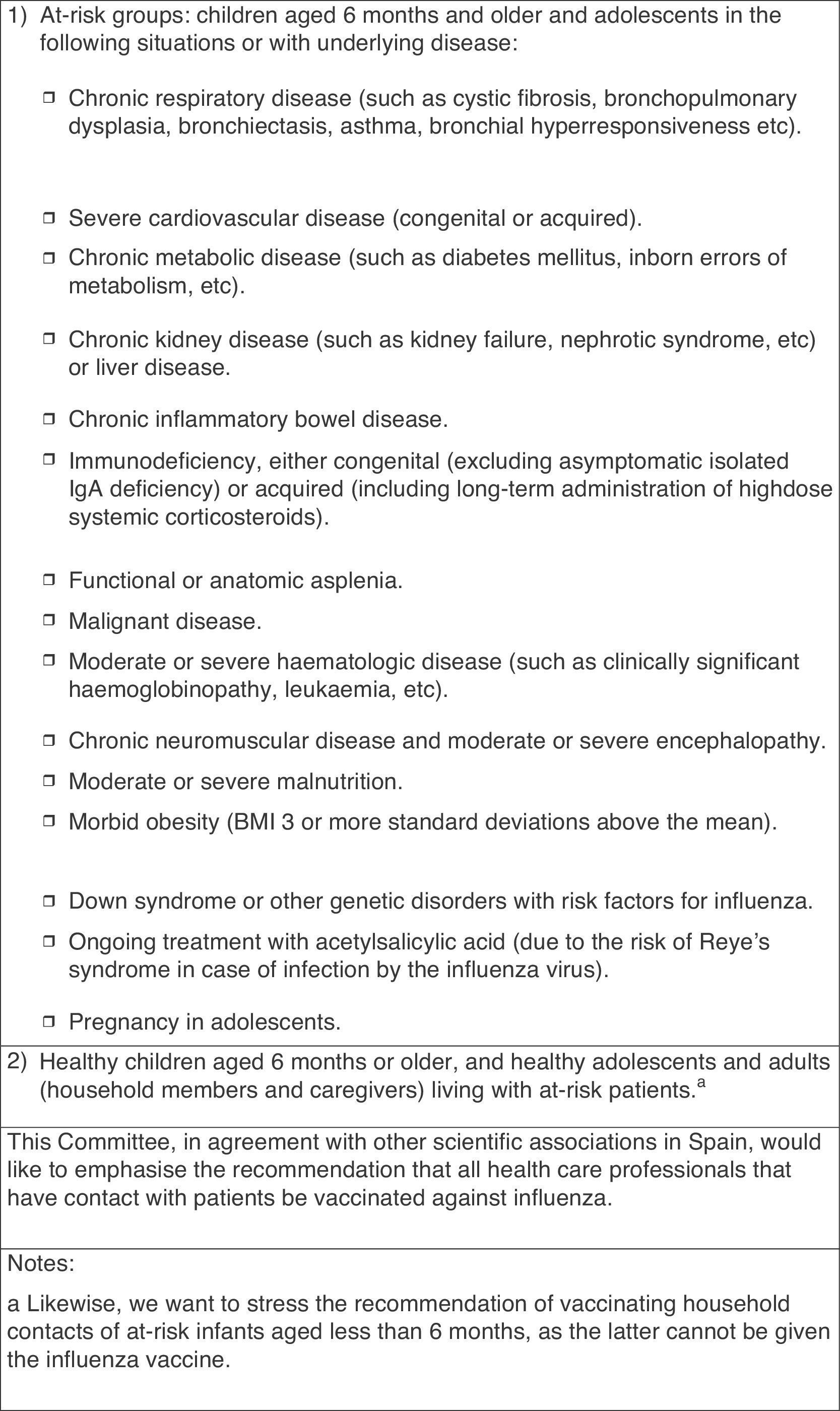

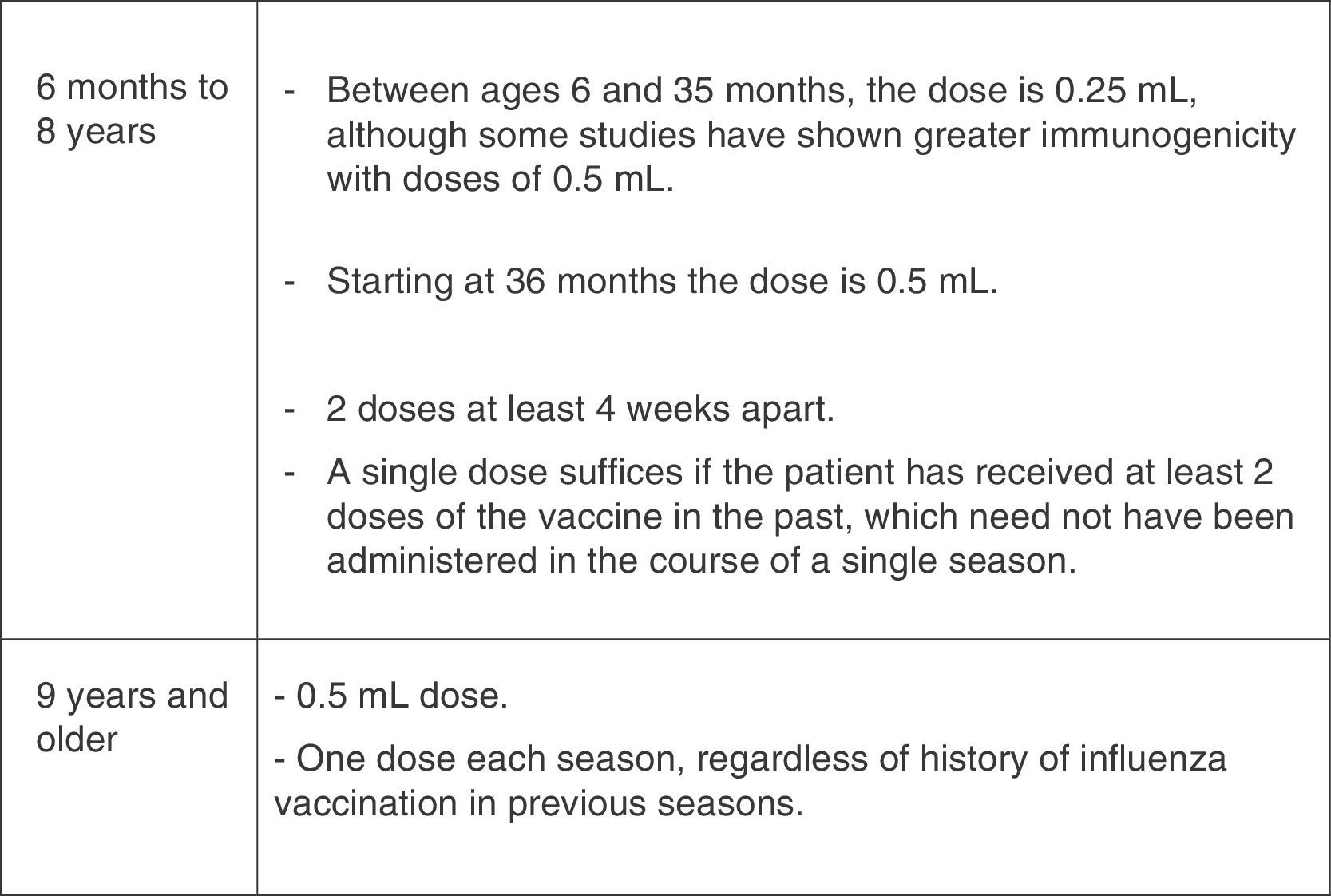

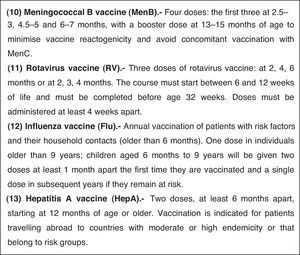

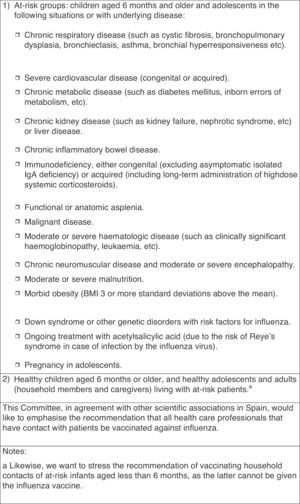

Vaccination against influenza2016 CAV-AEP recommendation: Vaccination against influenza is recommended for children and adolescents in the following circumstances: (a) risk groups: children aged 6 months and older and adolescents that are at risk due to specific circumstances or underlying disease; (b) children aged 6 months and older, adolescents and adults that are healthy and living with at-risk individuals.

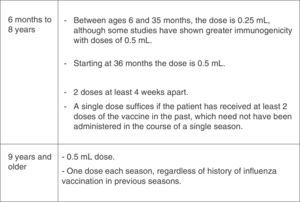

Fig. 6 summarises the recommendations of the CAV-AEP for vaccination against influenza, and Fig. 7 the dosage of the vaccine. Additional information can be found in the annual document released by this Committee specifically devoted to the influenza vaccine.37

Recommendations of the CAV-AEP for vaccination against seasonal influenza 2015–2016 (with trivalent inactivated vaccines).37

Dosage of the influenza vaccine by age and vaccination history.37

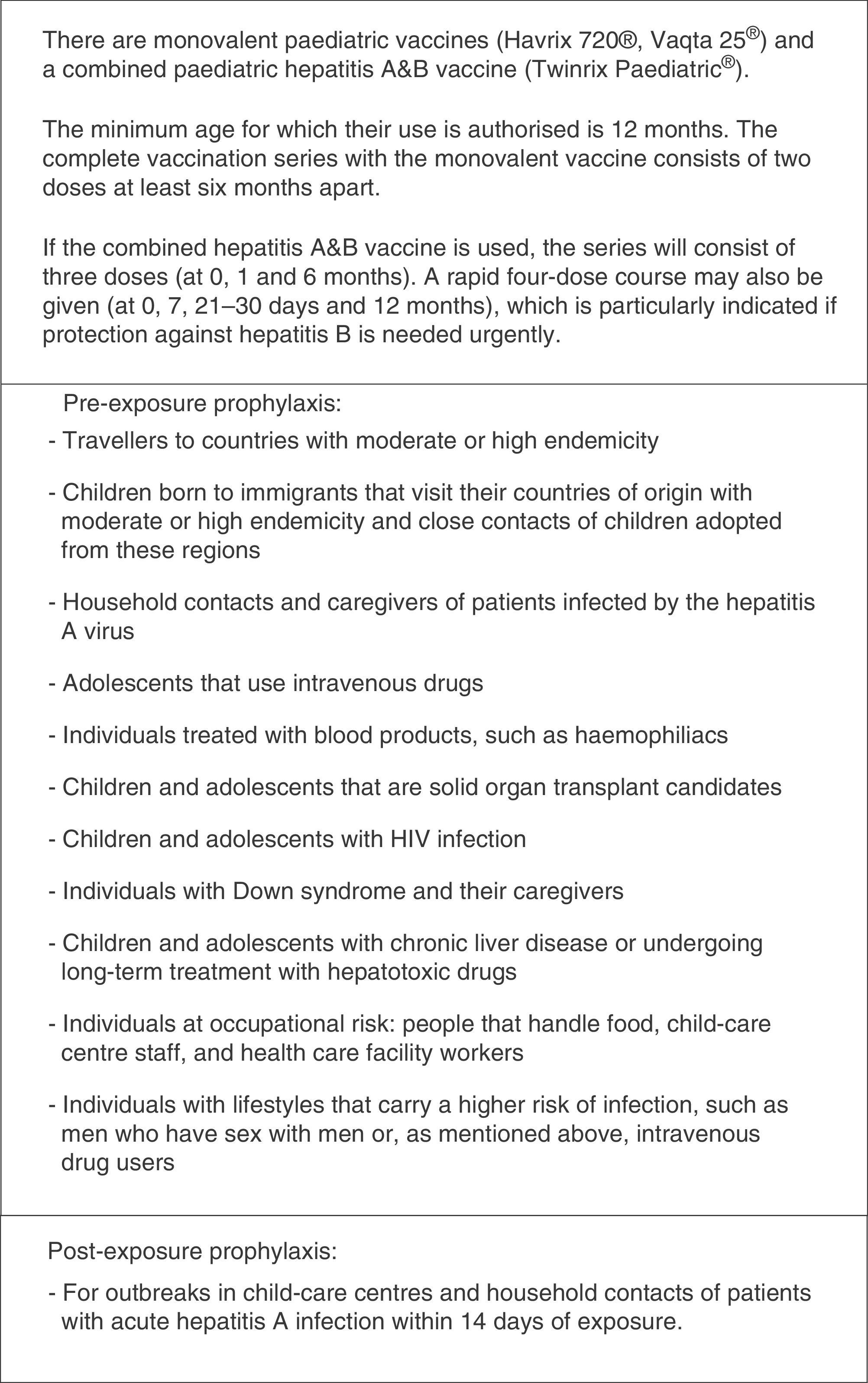

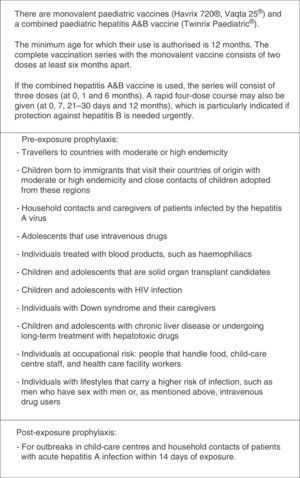

2016 recommendation: Vaccination against hepatitis A with 2 doses at least 6 months apart is recommended in specific risk situations. Its administration should be considered for children aged more than 12 months attending child-care centres.

The preparations, dosage and indications for this vaccine for children and adolescents at risk are presented in Fig. 8.38The vaccine has a 95% efficacy and it is estimated that anti-HVA antibodies persist for at least 14–20 years.39

Child-care centres that care for incontinent children are more likely to experience outbreaks of hepatitis A and transmit the virus to susceptible household contacts. For this reason, children aged more than 12 months that attend child-care centres could benefit from the administration of this vaccine, while benefitting their contacts indirectly.

Another special risk group are children born, most of them in Spain, to immigrants from endemic regions, as they are at a high risk of contracting the disease when they visit their countries of origin and subsequently transmitting the disease.40

FundingThe development of these recommendations (analysis of published data, debate, consensus and publication) was not funded by any sources other than the logistics facilitated by AEP.

Conflicts of interestLast 5 years:

- -

DMP has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD, as a researcher in clinical trials conducted by GlaxoSmithKline and as a consultant on the Astra-Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Pfizer advisory boards.

- -

FJAG has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD and as a consultant on GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis advisory boards.

- -

JAF has collaborated in educational activities and as a research in clinical trials funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD, and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis advisory boards.

- -

MJCO has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD, as a researcher in clinical trials conducted by Pfizer and as a consultant on GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD advisory boards.

- -

JMCR has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur MSD and Novartis.

- -

NGS has collaborated in educational activities funded by Sanofi Pasteur MSD and has attended educational activities funded by Novartis and Pfizer.

- -

AHM has received funding to attend domestic educational activities.

- -

THSM has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD and as a researcher in clinical trials funded by GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

- -

MMM has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD, as a researcher in clinical trials conducted by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD and as a consultant on a Novartis advisory board.

- -

LOC has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD and as a researcher in clinical trials conducted by GlaxoSmithKline.

- -

JRC has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur MSD and as a researcher in clinical trials conducted by GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

- -

David Moreno-Pérez. Infectología Pediátrica e Inmunodeficiencias. Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Pediatría. Hospital Materno-Infantil. Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga. IBIMA Research Group. Departamento de Pediatría y Farmacología. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad de Málaga.

- -

Francisco José Álvarez García. Pediatra. Centro de Salud de Llanera. Asturias. Profesor Asociado en Ciencias de la Salud. Departamento de Medicina. Universidad de Oviedo.

- -

Javier Arístegui Fernández. Unidad de Infectología Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario de Basurto. Bilbao. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU).

- -

María José Cilleruelo Ortega. Servicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

- -

José María Corretger Rauet. Consell Assessor de Vacunacions. Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya. Barcelona.

- -

Nuria García Sánchez. Pediatra. Centro de Salud Delicias Sur. Zaragoza. Profesora Asociada en Ciencias de la Salud. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad de Zaragoza.

- -

Ángel Hernández Merino. Pediatra. Centro de Salud La Rivota. Alcorcón. Madrid.

- -

Teresa Hernández-Sampelayo Matos. Servicio de Pediatría.

- -

Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- -

Manuel Merino Moína. Pediatra. Centro de Salud El Greco. Getafe. Madrid. Profesor Colaborador de la Facultad de Medicina. Universidad Europea. Madrid.

- -

Luis Ortigosa del Castillo. Servicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario Ntra. Sra. de Candelaria. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de La Laguna. Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

- -

Jesús Ruiz-Contreras. Servicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario 12 de octubre. Madrid. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Please cite this article as: Moreno-Pérez D, García FJÁ, Fernández JA, Ortega MJC, Rauet JMC, Sánchez NG, et al. Calendario de vacunaciones de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (CAV-AEP): Recomendaciones 2016. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;84:60.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics (CAV-AEP) are presented in Appendix.