Data about consumption of antibiotics in Spain are worrisome. They are mainly prescribed in the community sector and there is a high exposure to antibiotics in the pediatric population. The aim of this study is to describe the evolution of antibiotic consumption in the pediatric population of Asturias during 2005–2018 period.

MethodsRetrospective and descriptive study using data about consumption of antibacterial agents for systemic use (J01 group of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification) in pediatric outpatients in Asturias between 2005 and 2018. Data, expressed as defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID), in three periods were compared.

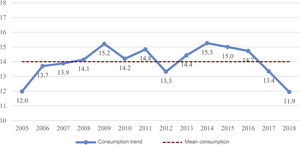

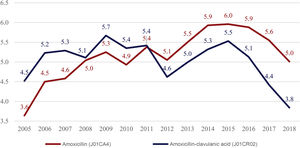

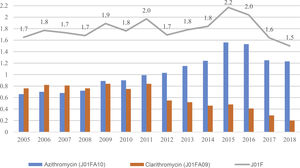

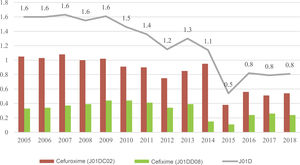

ResultsMean antibiotic consumption in pediatric outpatients in Asturias (2005–2018) was 14 DID (CI95% 13.4–14.6). Consumption increased until 2009 (15.2 DID) and decreased from 2015 onwards (11.9 DID in 2018). Remarkable data along the study were: 1) increase in amoxicillin consumption (p = 0.027), that have exceeded that of amoxicillin-clavulanate since 2011; 2) steady consumption of macrolides, with an increase in azithromycin (p < 0.001) and a decrease in clarithromycin (p = 0.001); 3) reduction of cephalosporins consumption (p < 0.001); 4) increase in quinolones consumption (p = 0.002).

ConclusionsGlobal antibiotic consumption in pediatric outpatients in Asturias between 2005 and 2018 has experienced a constant decrease lately and an improvement in patterns of antibacterial use.

El consumo de antibióticos en España es elevado y más del 90% de las prescripciones se realizan en ámbito extrahospitalario. La exposición a antibióticos en la edad infantil es alta. El objetivo de este estudio es describir la evolución del consumo extrahospitalario de antibióticos en la población pediátrica del Principado de Asturias entre 2005 y 2018.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo y retrospectivo del consumo de antibacterianos de uso sistémico (grupo J01 de la clasificación ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification) en ámbito extrahospitalario en la población pediátrica (0–13 años) del Principado de Asturias entre 2005 y 2018. Se compara el consumo, medido en número de dosis diarias definidas (DDD) por 1.000 habitantes y día (DHD), en 3 periodos de tiempo.

ResultadosEl consumo medio de antibacterianos en la población pediátrica asturiana (2005–2018) fue de 14 DHD (IC95% 13,4–14,6), con un aumento hasta 2009 (15,2 DHD) y descenso a partir de 2015 (11,9 DHD en 2018). A lo largo del estudio se detectó: 1) un aumento del consumo de amoxicilina (p = 0,027), que supera al de amoxicilina-clavulánico desde el año 2011; 2) un consumo estable de macrólidos, con un aumento de azitromicina (p < 0,001) y un descenso de claritromicina (p = 0,001); 3) un descenso del consumo de cefalosporinas (p < 0,001); 4) un aumento del consumo de quinolonas (p = 0,002).

ConclusionesEl consumo de antibióticos a nivel extrahospitalario en la población pediátrica del Principado de Asturias entre los años 2005 y 2018 ha experimentado un descenso mantenido en los últimos años y una mejora evolutiva del patrón de uso.

Excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics is the most important contributor to the development of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. In recent years, several strategies have been developed to confront both of these problems.1–3 In Europe, the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network (ESAC-Net) has been monitoring antibiotic use at the hospital and community levels in 31 European countries since 1997.2 The data evinces clear north-south and west-east gradients, with greater consumption and prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in countries in Southern and Eastern Europe.2,4 At the domestic level in Spain, in 2014 the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System approved the Plan Nacional de Resistencia a Antibióticos (National Plan on Antibiotic Resistance, PRAN) for surveillance of antibiotic use overall and of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in Spain, with its objectives including observing, limiting and improving antibiotic use in both animal and human health, and to promote and support antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance surveillance networks.3

More than 90% of the antibiotics consumed are prescribed at the outpatient level, mainly for management of respiratory tract infections. It is estimated that nearly half of antibiotic prescriptions in primary care are inappropriate, and unnecessary prescription is the main reason antibiotic use is deemed inappropriate.2,5 In 2018, Spain was the fourth leading country in antimicrobial consumption in the community in Europe.2

Antimicrobial consumption is greater at both ends of the lifespan. It is estimated that approximately 60% of children under 4 years are exposed to antimicrobials at least once a year.6,7 Yet, there are few population-based studies in Spain describing antimicrobial consumption in the paediatric population at the community level.8–10 Antimicrobial overuse in the paediatric population has significant repercussions, as the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance is up to 30% greater in isolates in community-acquired infections compared to isolates in the hospital setting.11,12

The aim of our study was to describe the use of antibiotics at the outpatient level in the paediatric population of Asturias, Spain, and analyse quantitative and qualitative temporal trends in antimicrobial use in the 2005–2018 period.

Material and methodsStudy design and settingWe conducted a retrospective study with a descriptive and comparative analysis of the annual consumption of antibacterials for systemic use (group J01 of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification [ATC]) at the outpatient level in the paediatric population (age 0–13 years) of Asturias between 2005 and 2018. We excluded the use of antibacterials not for systemic use and antiinfectives other than antibacterials, such as antifungals (J02), antimycobacterials (J04) and antivirals (J05).

The study universe was the entire paediatric population of Asturias. The public health system of the Department of Health of Asturias (Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias, SESPA) is divided in 9 health areas, each of which has a hospital offering paediatric care. As of January 1, 2019, the total population of Asturias was of 1 002 205 inhabitants, including 104 130 children under 14 years.13

Consumption dataWe obtained data on antimicrobial consumption from official medical prescription monthly payment records in the database of the Pharmacy Section of the Vice Directorate of Health Care Administration of the SESPA. We collected data on the units of systemic antibacterial drugs dispensed by pharmacies in Asturias for official prescriptions charged to the SESPA between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2018 made to patients aged 0–13 years. We aggregated data by national antimicrobial code, by levels 3 (therapeutic group), 4 (therapeutic subgroup) and 5 (chemical substance) in the ATC classification and by year.

Measures and indicators of antibiotic consumptionThe unit used to measure consumption was the defined daily dose (DDD) as described in the most recent update of the Collaborating Centre for Drugs Statistics Methodology of the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2019. The DDD is the international standard recommended by the WHO for drug utilization studies and is defined as the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults.14

The indicators of consumption analysed in the study were the number of DDD per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID) for the most widely used antibiotics and the number of DDD per 1000 inhabitants per year (DDD/1000/y) for chemical substances with a consumption corresponding to less than 0.5 DID, applying the following formulas:

The number of inhabitants in the denominator corresponded to the yearly number of paediatric patients with a public health care system card (Tarjeta Sanitaria Individual, TSI), which we obtained from the population and health care resources database of the Department of Public Health and Health Care Services of the SESPA, a datum published every year in the official health report.15

In the qualitative analysis, we used the J01_B/N indicator recommended by the ESAC-Net to assess antibacterial use patterns, which corresponds to the ratio of the consumption of broad-spectrum antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 2nd and 3rd generation cephalosporins and macrolides excluding erythromycin) to the consumption of narrow-spectrum antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins and macrolides (β-lactamase-sensitive penicillins, 1st generation cephalosporins and erythromycin) calculated as follows2:

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Asturias and exempted from informed consent on account of its being a population-based study. The authors adhered to the protocols established by health care facilities for access to health records.

Statistical analysisWe conducted the statistical analysis with the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0. Since antibiotic consumption is a quantitative variable that follows a normal distribution, we calculated means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We compared consumption in 3 periods (2005–2009, 2010–2014 and 2015–2018) by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Bonferroni correction. The significance level for all the inferential analyses was 0.05.

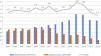

ResultsThe mean consumption of systemic antibacterials (group J01 in the ATC classification) dispensed by prescription in the community by the paediatric population of Asturias between years 2005 and 2018 was of 14 DIDs (95% CI, 13.4–14.6). The maximum difference in consumption found between time points (Fig. 1) was of 3.4 DIDs (maximum of 15.3 DIDs in 2014; minimum of 11.9 DIDs in 2018), and we found no significant differences in the comparison by periods (P = .6) (Table 1).

Consumption of antibiotic groups and subgroups by the paediatric population in Asturias (2005-2018), overall and by period.

| Group | Name | Overall consumption | Period 1 (2005−2009) | Period 2 (2010−2014) | Period 3 (2015−2018) | P | Differences between periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J01 | Antibacterials for systemic use | 14.0 DID | 13.8 | 14.4 | 13.8 | .600 | No |

| J01A | Tetracyclines | 35.3 DDD/1000/y | 22.3 | 42.0 | 43.1 | .033 | No |

| J01C | β-lactam penicillins | 10.7 DID | 10.3 | 11.1 | 10.9 | .404 | No |

| J01CA | Broad-spectrum penicillins | 5.2 DID | 4.6 | 5.4 | 5.6 | .027 | 1 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01CE | β-lactamase sensitive penicillins | 0.5 DID | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | .164 | No |

| J01CR | Combinations of penicillins | 5.0 DID | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | .399 | No |

| J01D | Other β-lactam antibacterials | 1.2 DID | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 | < .001 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01DB | First-generation cephalosporins | 3.5 DDD/1000/y | 2.8 | 2.5 | 5.6 | .040 | No |

| J01DC | Second-generation cephalosporins | 0.9 DID | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | < .001 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01DD | Third-generation cephalosporins | 130.8 DDD/1000/y | 159.2 | 145.7 | 80.1 | .011 | 1 ≠ 3; 2 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01E | Sulphonamides and trimethoprim | 27.5 DDD/1000/y | 30.4 | 25.9 | 25.9 | .096 | No |

| J01F | Macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins | 1.8 DID | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | .739 | No |

| J01FA | Macrolides | 1.8 DID | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | .760 | No |

| J01FF | Lincosamides | 1.4 DDD/1000/y | 0.7 | 1.1 | 2.5 | .003 | 1 ≠ 3; 2 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01M | Quinolones | 5.2 DDD/1000/y | 4.0 | 4.9 | 7.2 | .002 | 1 ≠ 3; 2 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01X | Other antibacterials | 12.2 DDD/1000/y | 8.8 | 13.9 | 14.2 | .001 | 1 ≠ 2; 1 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01XE | Nitrofuran derivatives | 3.51 DDD/1000/y | 2.8 | 4.8 | 2.8 | .104 | No |

| J01XX | Other antibacterials | 8.56 DDD/1000/y | 5.9 | 9.0 | 11.4 | < .001 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 (increase) |

DDD, daily defined dose; DID, number of DDD/1000 inhabitants/day.

The distribution of the different therapeutic groups by decreasing frequency was: J01C (β-lactam penicillins), 10.7 DIDs (76.7% of total consumed); J01F (macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins), 1.8 DIDs (12.8%); J01D (other β-lactam antibacterials, which refers to cephalosporins), 1.2 DIDs (8.9%); J01A (tetracyclines), 35.3 DDD/1000/y (0.7%); J01E (sulphonamides and trimethoprim), 27.5 DDD/1000/y (0.5%); J01X (other antibacterials), 12.2 DDD/1000/y (0.2%); J01M (quinolones), 5.2 DDD/1000/y (0.1%). The most frequently consumed chemical substances were amoxicillin (J01CA04; 5.2 DID), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (J01CR02; 5 DID), azithromycin (J01FA10; 1 DID), cefuroxime (J01DC02; 0.8 DID) and clarithromycin (J01FA09; 0.6 DID) (Table 2).

Consumption of the 10 most frequently used antibiotics in the paediatric population in Asturias (2005–2018), overall and by period.

| Substance code | Name | Overall consumption | Period 1 (2005−2009) | Period 2 (2010−2014) | Period 3 (2015−2018) | P | Differences between periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J01CA04 | Amoxicillin | 5.2 DID | 4.6 | 5.4 | 5.6 | .027 | 1 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01CR02 | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 5.0 DID | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | .399 | No |

| J01FA10 | Azithromycin | 1.0 DID | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 | < .001 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01DC02 | Cefuroxime | 0.8 DID | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | < .001 | 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01FA09 | Clarithromycin | 0.6 DID | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | .001 | 1 ≠ 3; 2 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01CE02 | Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 119.5 DDD/1000/y | 106.3 | 117.7 | 138.4 | .059 | No |

| J01DD08 | Cefixime | 116.2 DDD/1000/y | 137.5 | 126.0 | 77.4 | .029 | 1 ≠ 3 (decrease) |

| J01CE10 | Phenoxymethylpenicillin-benzathine | 78.2 DDD/1000/y | 70.7 | 87.6 | 76.0 | .174 | No |

| J01AA02 | Doxycycline | 31.5 DDD/1000/y | 17.4 | 37.8 | 41.1 | .019 | 1 ≠ 3 (increase) |

| J01EE01 | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 21.5 DDD/1000/y | 22.4 | 20.5 | 21.6 | .591 | No |

DDD, daily defined dose; DID, number of DDD/1000 inhabitants/day.

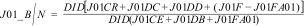

Amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid accounted for 94.9% of consumption in the J01C group and 72.8% of overall consumption. In the first period, the consumption of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was greater compared to the consumption of amoxicillin, a trend that reversed from 2011 (Fig. 2). There was a significant increase in the consumption of amoxicillin between the first and last periods under study (P = .027), while the decrease in the use of e amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was not statistically significant (P = .399) (Table 2).

Consumption of antibacterials in the J01 F group remained stable throughout the study period (P = .739) (Table 1). Azithromycin and clarithromycin accounted for 91.6% of the consumed antibacterials belonging to group J01F. We found an increase in the use of azithromycin (P < .001) and a decrease in the use of clarithromycin (P = .001) (Table 2). From 2009, the consumption of azithromycin exceeded the consumption of clarithromycin, with the difference increasing through the end of the study period (differences of 0.1 DID in 2009 and 1.1 DID in 2016), as can be seen in Fig. 3.

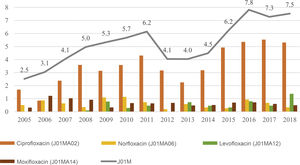

In the J01D group, cefuroxime and cefixime accounted for 91.9% of the consumption. The frequency of consumption of J01D group antibacterials, cefuroxime and cefixime all decreased in the period under study (P < .001, P < .001 and P = .029, respectively) (Tables 1 and 2). Consumption of drugs in this therapeutic group reached the minimum in 2015 (0.5 DID) (Fig. 4). Consumption of antibacterials in all other groups amounted to 1.5% of the total. The use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remained stable through time (P = .591), while there were significant increases in the consumption of doxycycline (P = .019), fosfomycin (group J01XX; P < .001) and ciprofloxacin (P = .001). The consumption of quinolones was 3 times greater in 2018 compared to the first year under study (Fig. 5).

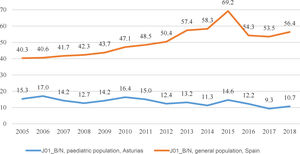

The J01_B/N quality indicator in our study was below the ratios corresponding to the total population of Spain and also improved over time, with ratios around 10 in the last few years (Fig. 6).

DiscussionThe DDD is the standard recommended by the WHO to perform drug utilization studies.14 However, one of its main drawbacks is that it may underestimate consumption in the paediatric population and may not accurately reflect the doses used or recommended in everyday clinical practice. Although other parameters have been studied for the purpose of assessing antibiotic consumption in paediatric inpatients, such as the DDD adjusted for weight or days of treatment, the ideal measure of antibiotic consumption in the paediatric population has yet to be identified. Some of these indicators also require information that is usually not accessible in drug utilization studies that analyse consumption in the community and in large populations.16–18

The WHO updates DDDs regularly according to changes in dosage for the main indications for each drug. The latest update took place in 2019 and included adjustments in the DDDs of the most frequently consumed antibiotics in Spain, amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. The data of this study were updated based on this latest review and can thus be compared, with the drawbacks that we already mentioned, with the data published by the ESAC-Net. The consumption in the paediatric population of Asturias increased progressively in the first time interval, from 12 DID in 2005 to 15.2 DID in 2009, and decreased from 2015, reaching levels similar to those found at the beginning of the study. Every year, consumption in Asturias was lower compared to consumption in the general population of Spain with a relatively parallel trend until 2015. In recent years, the evidence shows an excessive use of antibacterials at the outpatient level in our country that places Spain among the countries in Europe with the greatest consumption.2,3 Studies conducted in different regions in Spain have also reported a substantial exposure of the population to antibiotics and an increase in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics through the years.6,7,19–22

Five antibiotics accounted for 90.5% of the total consumption, and amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, in particular, accounted for 75% of the total. In the adult population, there has been an increase in the use of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, which has exceeded the consumption of amoxicillin since the early 2000s, reaching 56% of total outpatient prescriptions in 2018.2,6,7,19–21,23,24 Frequent prescription of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in the paediatric population is not justified given the infections usually managed at the outpatient level, as most are caused by bacteria that do not produce β-lactamases, such as Streptococcus pyogenes or Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vázquez et al. described a predominant use of amoxicillin over its combination with clavulanic acid since 2005 in the paediatric population of Castilla y Leon.10 We identified this shift in the paediatric population of Asturias since 2011, and the gap widened over time, which reflects an improved pattern of consumption. Although the consumption of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in the population under study did not change significantly between periods, we ought to highlight a decrease of 26% in the use of this active ingredient in the last period under study.

Consumption of drugs in the macrolides therapeutic group remained stable in our population. However, we ought to warn of a sharp increase in the consumption of azithromycin over the study period, which is all the more remarkable given that fewer DDDs are required per course of treatment with this drug. The main consequence of the excessive use of any antibiotic is the development of antimicrobial resistance, but the potential side effects of the administration of any drug must also be considered, and in this case it is important to be aware of the recent report on the risk of severe arrhythmia associated with the use of azithromycin in children.25 In the United States, there is evidence that azithromycin is prescribed too frequently and inappropriately in the paediatric population (second most frequently prescribed antibiotic), a practice that is currently the main target of antibiotic stewardship programmes at the outpatient level in the country.26

The decrease in the consumption of cephalosporins in the paediatric population of Asturias, especially steep in 2015, could be explained by a shortage of cephalosporins at the time, a situation that prompted an alert by the Committee on Medicines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Paediatrics) due to the short supply of oral solutions in a widely used therapeutic group with special indications in young children.6,7,27,28

Quinolones are the third most widely used therapeutic group at the outpatient level in the general Spanish population (11% of total consumption) and the most frequently prescribed group in the population over 75 years.2,6,7 Although the consumption of quinolones in our study was very small (0.1% of the total), there was a significant increase over the period under study that should be monitored in future studies.

The ESAC group proposed the J01_B/N as a quality indicator for antibacterial use at the outpatient level. This ratio allows comparison between European countries, which has evinced significant variation, with the lowest ratios found in Norway (0.16) and Sweden (0.21) and the highest in Greece (624) and Italy (226) in 2018.2 Malo-Fumanal et al. found significant quantitative and qualitative differences in antibiotic utilization between Spain and Denmark, with a greater consumption, overall and of cephalosporins and broad-spectrum penicillins in every age group and quinolones in the adult population, in Spain.29 Thus, in 2018 the J01_B/N ratio in Spain was 59.4 compared to 0.6 in Denmark.2 In our study, we found a decrease in this indicator throughout the study period, which reflects an improvement in the patterns of antibiotic use. In contrast, this same indicator was noticeably higher and was increasing over the same period in the general population of Spain.

There are limitations to our study, chiefly those common to drug utilization studies with similar methodology based on data retrieved from pharmacy records. We obtained data on the dispensation in community pharmacies of drug prescriptions funded by the SESPA, but did not include data for dispensation without prescription (self-medication) or of prescriptions issued from the private health care system or other insurers. Since 2002, a medical prescription is required in Spain for dispensation of an antibiotic agent in pharmacies. The volume of antibiotics dispensed through health insurance companies and prescriptions by private physicians is not small, although in Asturias it is below the national average; in 2019, Asturias ranked second last of all autonomous communities in Spain in the dispensation of antibiotics prescribed outside the public health service.30 In addition, the coverage of the paediatric population of Asturias by the public health system is high (98% in year 2018).15 We did not analyse consumption at the hospital level, as we know that it is very small in proportion to consumption in the community after a quantitative study in one of the central health areas found that it amounted to 1.5% of the overall consumption. We did not analyse consumption by age group, seasonal patterns in prescription or the appropriateness and suitability of antibiotherapy prescriptions. Lastly, we did not analyse prescriptions made exclusively by paediatricians, but all prescriptions made by any physician that managed paediatric patients in the period under study in primary care or after-hours urgent care centres, as we sought to assess the actual exposure of the paediatric population to antibiotic agents.

In conclusion, our study, conducted in the paediatric population of one autonomous community in Spain and spanning 14 years, found a decrease in the overall consumption of antibiotics at the outpatient level in recent years and a more rational use of these drugs. We ought to highlight and warn of the marked increase in the consumption of azithromycin and quinolones throughout the period under study. It is important that physicians be aware of local antimicrobial consumption patterns to be able to implement antimicrobial stewardship strategies and identify the determinants of antimicrobial prescription for the purpose of containing the development of antibacterial resistance.

FundingThe study received a €500 grant from the Fundación Ernesto Sánchez Villares (FESV) of the Sociedad de Pediatría de Asturias, Cantabria y Castilla y León (SCCALP).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Calle-Miguel L, Iglesias Carbajo AI, Modroño Riaño G, Pérez Méndez C, García García E, Rodríguez Nebreda S, et al. Evolución del consumo de antibióticos a nivel extrahospitalario en Asturias, España (2005–2018). An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;95:438–447.

Previous presentation: partial results of this study were presented under the title «Increase and high variability in consumption of antimicrobial agents for systemic use in the paediatric population in Northern Spain. Time period 2005–2015» at the 37th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID); May 6–11, 2019, Ljubljana, Slovenia.