The care at the end of children's lives must be sensitive to the needs of the child and their family. An understanding of the illness is required from the perspective of parents faced with the death of their child, in order to improve quality and guide the development of end-of-life care in Paediatrics.

MethodA retrospective observational study was conducted between June 2014 and June 2017 using a questionnaire, to assess the needs, experiences, and satisfaction with the care received, from a sample of parents who lost a child due to a foreseeable cause. Three different study groups were formed based on the team responsible for end-of-life care, and an analysis was carried out on the differences between the group treated by the paediatric palliative care team, the group attended by non-palliative paediatricians, and the neonatal group.

ResultsOf the 80 eligible families, 64 could be contacted, and 28 (43.8%) finally completed the questionnaire. Our study shows positive experiences and high satisfaction of parents with the care received at the end of their child's life. The highest scores in experiences and satisfaction were given by the parents of the children served by the paediatric palliative care team, with statistically significant differences in family support, communication, shared decision making, and bereavement support (P<.05).

ConclusionsParents are satisfied with the care received at the end of their children's lives, but the intervention of a specific paediatric palliative care team improves the quality of care at the end of life in paediatrics.

La atención al final de la vida de los niños debe ser sensible a las necesidades del niño y de su familia. Necesitamos entender la enfermedad desde la perspectiva de los padres que se enfrentan a la muerte de su hijo, para poder mejorar la calidad y guiar el desarrollo de la atención al final de la vida en Pediatría.

MétodoEstudio observacional retrospectivo a través de cuestionario, para evaluar las necesidades, experiencias y satisfacción con la atención recibida, de una muestra de padres que perdieron un hijo por una causa previsible, entre junio de 2014 y junio de 2017. Diferenciamos tres grupos de estudio en función del equipo responsable de la atención al final de la vida, y las diferencias entre el grupo atendido por el equipo de cuidados paliativos pediátricos, el grupo atendido por pediatras no paliativistas y el grupo neonatal, son analizadas.

ResultadosDe las 80 familias elegibles, 64 pudieron ser contactadas y 28 (43,8%) finalmente completaron el cuestionario. Nuestro estudio muestra experiencias positivas y alta satisfacción de los padres con la atención recibida al final de la vida de su hijo. Las puntuaciones más altas tanto en experiencias como en satisfacción, fueron otorgadas por los padres de los niños atendidos por el equipo de cuidados paliativos pediátricos con diferencias estadísticamente significativas en apoyo a la familia, comunicación, toma de decisiones compartida y atención en torno a la muerte (p<0,05).

ConclusionesLos padres están satisfechos con la atención recibida al final de la vida de sus hijos, pero la intervención de un equipo específico de cuidados paliativos pediátricos mejora la calidad de la atención al final de la vida en pediatría.

Children with life-threatening or life-limiting diseases require comprehensive care that is not limited to physical care, but also addresses and acknowledges the psychological, social and spiritual needs of children and their families.

Many countries have recognised the need for paediatric palliative care (PPC) units to deliver comprehensive care to children with life-threatening or life-limiting diseases and their families.1,2 In Spain, the PPC field has expanded significantly since 2005, although with significant variations between and within its autonomous communities. However, few studies have analysed the effectiveness of PPC teams. In 2007, a study conducted in south-east Bavaria (Germany) assessed the satisfaction of parents with the care delivered by a PPC team. With a response rate of 88%, the survey showed that parents believed that the involvement of the PPC team resulted in very significant improvements in symptom management and quality of life in the children and in communication, support to the family and streamlining of administrative processes (P<.001).3 Another study, conducted in Sweden in 2001, found that professional and social support through the process of grieving had a positive long-term impact on parents that lost a child to cancer.4

Since June 2014, the Department of Paediatrics of the Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (HCUVA) has a PPC team that delivers home-based and in-hospital services with a multidisciplinary staff (physicians, nurses, psychologists and social worker) especially trained in palliative care, end-of-life care and grief counselling. In the Department of Paediatrics of the HCUVA, the end-of-life care for children with life-threatening or life-limiting disease is sometimes delivered by the PPC team, but in many cases it is delivered by the original care team (neonatology, paediatric neurology, paediatric oncology) or paediatric intensive care specialists.

We sought to deepen our understanding of the needs and experiences of parents in our population facing the death of their children and to assess their perception of the care received during this difficult time in their lives with the ultimate purpose of improving quality and inform the development of end-of-life care in paediatric practice. The primary objective of our study was to assess the effectiveness of the PPC team, that is, whether the involvement of the PPC team improved end-of-life care base on the experience and the level of satisfaction of parents with the care received.

MethodsStudy design and universeWe conducted a retrospective observational study by means of a questionnaire to assess patient needs and end-of-life care as perceived by parents who lost children to predictable causes of death between June 2014 and June 2017 in the Department of Paediatrics of the HCUVA.

We classified participants into 3 groups based on the team responsible for delivering end-of-life care:

- •

PPC group, managed by the PPC team.

- •

Non-PPC group, managed by paediatricians not specialised in palliative care: the original care team (paediatric neurology or oncology) or the paediatric intensive care unit team.

- •

Neonatal group, managed by the neonatal intensive care unit team. The PPC team was also not involved in the care of the neonatal group, but we wanted to differentiate this subset due to the particular characteristics of death in the first month of life and the high complexity of the required care, which precluded the discharge from hospital of the patient before death.

We invited to participate all parents of a child managed in the Department of Paediatrics of the HCUVA that died between June 2014 and June 2017 as a result of a life-threatening or life-limiting disease (defined based on the classification of the Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families of 19975) and able to read Spanish. We excluded parents whose child died within 24h of birth.

To assess the perceptions of parents, we used the Parental PELICAN questionnaire (PaPEQu), designed and validated in Switzerland in the framework of the Paediatric End-of-LIfe CAre Needs project (PELICAN, 2012–2015, NCT01983852).6,7 The PaPEQu allows the retrospective evaluation of parental experiences and needs during their child's end-of-life care and to evaluate the quality of paediatric and neonatal care as perceived by parents.6 We translated the Italian version of the questionnaire to Spanish following the international guidelines for the translation of questionnaires of the Global Asthma Network published in 2015.8

The PaPEQu is structured into 6 thematic domains regarding the quality of family-centred cared, identified by the Initiative for Paediatric Palliative Care investigator team9 and adapted by Truog et al.10 The 6 domains conform to the evidence that is currently available and are: (1) support of the family unit, (2) communication, (3) shared decision-making, (4) relief of pain and other symptoms, (5) continuity and coordination of care and (6) bereavement support.7 Each domain includes items that assess the needs of parents and items that assess their experiences. Lastly, parents are asked to rate their overall satisfaction with each domain of care. The questionnaire also has open-ended questions asking parents to describe 3 positive and 3 negative experiences related to their child's end-of-life care.

We used 2 slightly different versions of the PaPEQu: the neonatal version and the general version. Appendix A presents the full list of items in each of the Spanish versions of the PaPEQu.

Data processing and analysisWe set an α level of 5% in the tests used for comparison of the 3 groups of parents. When the dependent variable was quantitative, we used the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. In addition, to compare parents two by two, we used the Mann–Whitney U as a nonparametric post hoc test with the Bonferroni correction to protect from the increased probability of a type 1 error. When the dependent variable was qualitative, we compared the 3 groups of parents with the likelihood ratio. We performed all the statistical analysis with the software SPSS 19.0.

ResultsRecruitment and characteristics of the sampleFig. 1 presents the recruitment process for obtaining the study sample.

We telephoned parents that met the inclusion criteria and whose child had not died in the first 24h post birth to give them information about the study and request their participation. If families agreed to participated, we mailed an envelope to the home containing a letter that presented the study, the informed consent form and 2 questionnaires. We considered submission of a completed questionnaire a formal agreement to participation in the study. We recruited families between July and August of 2017.

The participation rate was of 43.8%, corresponding to 28 of the 64 eligible families that we were able to get in touch with. Participation was similar in the 3 groups under study (Fig. 1).

We sent 2 copies of the questionnaires to the 55 families that initially agreed to participate in the study (1 for the father and 1 for the mother). Thus, we sent out a total of 108 questionnaires (there were a few single parent households) and we received 46 completed questionnaires from 28 families (response rate of 42.6%).

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample of deceased children by study group. The largest was the neonatal group (n=12), which included premature newborns with respiratory, gastrointestinal, infectious or neurologic complications and 1 newborn with polymalformative syndrome.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and place of death of children in the sample by study group and overall.

| Characteristics of deceased children | CPP | No CPP | Neonatal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=9 | n=7 | n=12 | N=28 | |

| (32%) | (25%) | (43%) | (100%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 5 (41.7%) | 12 (42.9%) |

| Female | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (58.3%) | 16 (57.1%) |

| Age of death | ||||

| In months, mean (SD) | 66.89 (61.0) | 82.29 (67.6) | 0.33 (0.2) | 42.21 (59.3) |

| Type of disease, n (%) | ||||

| Neurologic | 5 (55.6%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (21.4%) |

| Oncological | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (32.1%) |

| Cardiovascular | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) |

| Neonatal | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) | 12 (42.9%) |

| Place of death, n (%) | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 0 (0%) | 3 (42.8%) | 12 (100%) | 15 (53.6%) |

| Inpatient ward | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.1%) |

| Home | 9 (100%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (35.7%) |

| Other setting | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) |

n, absolute frequency; N, total sample size; SD, standard deviation; %, percentage of group/column.

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the parents that participated in the study. Mothers participated in a greater proportion compared to fathers. The majority of participants were native Spaniards (89.1%), while 10.9% of parents were immigrants.

Sociodemographic characteristics of parents by study group and of the overall sample.

| Characteristics of parents | PPC | Non-PPC | Neonatal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=15 | n=8 | n=23 | N=46 | |

| (32.6%) | (17.4%) | (50%) | (100%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Father | 6 (40%) | 1 (12.5%) | 11 (47.8%) | 18 (39.1%) |

| Mother | 9 (60%) | 5 (62.5%) | 12 (52.2%) | 26 (56.5%) |

| Agea, mean (SD) | ||||

| Fathers | 38.33 (6.2) | – | 35.82 (5.5) | 36.71 (5.7) |

| Mothers | 32.78 (13.4) | 33.4 (6.8) | 32.92 (5.0) | 32.96 (8.7) |

| Nationality, n (%) | ||||

| Spanish | 15 (100%) | 6 (75%) | 20 (87%) | 41 (89.1%) |

| Moroccan | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Honduran | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Ecuadorian | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Ukrainian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| First language, n (%) | ||||

| Spanish | 15 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 20 (87%) | 43 (93.5%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 3 (6.5%) |

| Current marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married/partnered | 15 (100%) | 4 (50%) | 22 (95.7%) | 41 (89.1%) |

| Divorced/separated | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Single | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Religious affiliation, n (%) | ||||

| Catholic | 10 (66.7%) | 3 (37.5%) | 17 (73.9%) | 30 (65.2%) |

| Protestant | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Muslim | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Evangelist | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| None | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 3 (13%) | 9 (19.6%) |

| Number ofchildrenb, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 6 (40%) | 2 (25%) | 9 (39.1%) | 17 (37%) |

| 2 | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 9 (39.1%) | 17 (37%) |

| 3 | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (25%) | 5 (21.7%) | 11 (23.9%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Previous loss of children, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (17.4%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| No | 15 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 19 (82.6%) | 42 (91.3%) |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||||

| Primary/elementary education | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Compulsory secondary education/middle school | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (50%) | 7 (30.4%) | 16 (34.8%) |

| Noncompulsory secondary education/high schoolc | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| High-level vocational educationd | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 3 (6.5%) |

| Associate's degree | 3 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (13%) |

| Bachelor's degree | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 6 (13%) |

| No education | 4 (26.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (13%) |

| Employment status prior to death of child, n (%) | ||||

| Actively employed | 6 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (43.5%) | 16 (34.8%) |

| Inactivee | 9 (60%) | 6 (75%) | 13 (56.5%) | 28 (60.9%) |

| Employment status at the time of the survey, n (%) | ||||

| Actively employed | 11 (73.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 16 (69.6%) | 28 (60.9%) |

| Inactivee | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 15 (32.6%) |

| Gross household income, n (%) | ||||

| <16,000 € | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 8 (17.4%) |

| 16000–30000 € | 8 (53.3%) | 2 (25%) | 6 (26.1%) | 16(34.8%) |

| 31000–51000 € | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 5 (10.9%) |

n, absolute frequency; N, total sample size; SD, standard deviation; %, percentage of group/column.

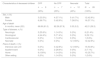

The scores in the need-related items were high, with little variation between the 3 groups, with the exception of items pertaining bereavement support (domain 6). In this domain of quality of care, parents in the different groups differed in the importance they assigned to each of the needs that the questionnaire asked about (Fig. 2).

In the overall sample, the needs that felt most important to parents in end-of-life care were choosing the place of death (mean, 4.52; standard deviation [SD], 2.09), receiving support from the care team in the hours following the death of the child (mean, 4.40; SD, 1.95) and giving families and/or friends the opportunity to say goodbye to the child (mean, 4.37; SD, 2.11).

For parents in the PPC group, choosing the place of death was significantly more important than for parents in the other 2 groups (P<.05). Parents of newborns ascribed significantly less importance to the presence of members of the care team in the child's funeral compared to parents in the other 2 groups (P<.01). Compared to parents in the PPC group, parents of newborns also ascribed less importance to the opportunity for family and/or friends to say goodbye to the child (P<.01) and to keeping in touch with someone from the care team after the child's death (P<.01).

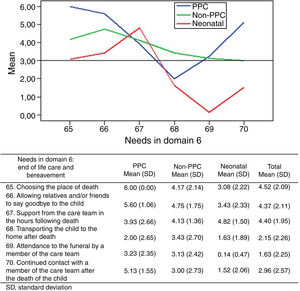

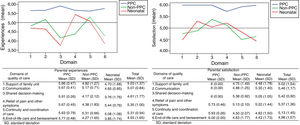

Parental experiences and satisfaction with the care receivedIn general, parents rated their experiences with the end-of-life care of their children as positive (Fig. 3). In the overall sample, the highest scores corresponded to the domains of relief of pain and other symptoms (mean, 5.35; SD, 1.0) and the continuity and coordination of care (mean, 5.31; SD, 0.94). The lowest scores corresponded to bereavement support (mean, 4.55; SD, 1.65) and shared decision-making (mean, 4.61; SD, 1.77).

Parents of children managed by the PPC team reported the most positive experiences in the 6 domains of quality of care, with significantly higher scores in the support of the family unit, communication, shared decision-making and bereavement support domains (P<.05). Parents in the neonatal group reported the least positive experiences in every domain except the relief of pain and other symptoms, in which the least positive experiences were reported by the non-PPC group.

The scores parents gave to their overall satisfaction with the received end-of-life care were higher compared to the scores given to their experiences (Fig. 3). In the overall sample, the highest scores were given to the domains of communication (mean, 5.46; SD, 1.17) and shared decision-making (mean, 5.42; SD, 0.92). The lowest scores corresponded to bereavement support (mean, 4.98; SD, 1.57) and support of the family unit (mean, 5.02; SD, 1.54).

In agreement with the reported experiences, the satisfaction of parents in the PPC group was higher in the 6 domains of quality of care, with significantly higher scores given in every domain (P<.05) except relief of pain and other symptoms.

In the non-PPC and neonatal groups, we found differences in how parents rated experiences versus satisfaction (Fig. 3). The satisfaction with shared decision-making of parents in the non-PPC and neonatal groups was higher than expected. Although based on the section devoted to experiences decision-making “was not discussed”, parents agreed with the decisions made and accepted them well. Similarly, in the non-PPC group, while parents reported having the experience that relief of pain and other symptoms “was not achieved”, they expressed a high degree of satisfaction with the implemented interventions and the management of pain and other symptoms.

Support of the family unitDuring the illness, children and their parents had access to a wide range of support services. In the overall sample, the services used most frequently were psychological support (47.8%), grief counselling (28.3%) and spiritual counselling (26.1%). The neonatal group had the least access to these support services: 34.8% of parents in this group reported having access to none of these services, and only 17.4% received psychological support.

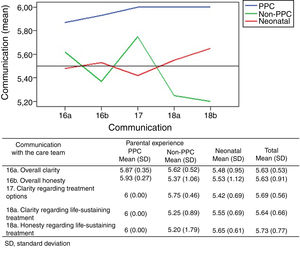

Communication with the health care teamIn general, parents reported very positive experiences in their communication with the health care team in charge of the patient (Fig. 4). Once more, the most positive experiences were reported by parents in the PPC group.

We asked parents in the PPC and non-PPC groups about what the child had been told about his or her impending death; 69.6% of parents stated that their children could not be informed due to their young age or mental status, while 21.7% did not want death to be discussed with their children. Only 2 children were told that they were going to die.

Shared decision-makingThe experiences of parents in shared decision-making corresponded to the lowest scores in the 6 domains of quality of care in the non-PPC (mean, 4.17; SD, 2.12) and neonatal (mean, 3.76; SD, 1.76) groups. However, the overall level of satisfaction of the parents with this domain was high (Fig. 3).

In the total sample, 50% of parents considered that they had made a decision regarding the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in their children (Table 3). A much greater proportion of parents were involved in this decision in the group managed by the PPC team (73.3%; P=.1). Parents reported that decisions regarding resuscitation were made jointly by the family and care team in 52.2% of cases.

Description of the decision-making process regarding resuscitation and withdrawal or withholding of treatment.

| Decision-making | PPC | Non-PPC | Neonatal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=15 | n=8 | n=23 | N=46 | |

| (32.6%) | (17.4%) | (50%) | (100%) | |

| 1. Was a decision made about using or not using CPR measures?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (73.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 9 (39.1%) | 23 (50%) |

| No | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | 22 (47.8%) |

| 2. Who made the decision to use or not use CPR measures?, n (%) | ||||

| Not discussed | 6 (40%) | 3 (37.5%) | 14 (60.9%) | 23 (50%) |

| Only 1 parent | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| The family | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| The care team | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 3 (13%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| The family and the care team together | 7 (46.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 12 (26.1%) |

| 3. Did the care team announce the withdrawal of therapeutic interventions that had become ineffective?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 15 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 18 (78.3%) | 41 (89.1%) |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 3 (6.5%) |

| 4. Who made the decision to withdraw or not withdraw ineffective treatments?, n (%) | ||||

| Not discussed | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (25%) | 6 (26.1%) | 10 (21.7%) |

| Only 1 parent | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| The family | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| The care team | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 9 (39.1%) | 14 (30.4%) |

| The family and the care team together | 10 (66.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 15 (32.6%) |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; LR, likelihood ratio; n, group size; N, total sample size; %, percentage of the group.

1. LR(2)=4.611; P=.100 (difference not statistically significant). 2. LR(8)=11.120; P=.195 (difference not statistically significant). 3. LR(2)=4.679; P=.096 (difference not statistically significant). 4. LR (8)=14.224; P=.076 (difference not statistically significant).

When it came to the withdrawal or withholding of treatment, 89.1% of parents confirmed that they had been informed of the discontinuation of ineffective treatments (Table 3). In the PPC group, 66.7% of parents reported that the decision to withdraw these treatments was made jointly by the family and the care team. In contrast, higher proportions of parents in the non-PPC and neonatal groups reported that this decision was made independently by the care team (37.5% and 50%, respectively).

Relief of pain and other symptomsThe symptoms that concerned parents the most at the end of their children's lives, selected out of a list with more than 10 options, were respiratory distress and pain.

Continuity and coordination of careWe asked parents in the PPC and non-PPC groups about the health care staff that was most involved in supporting them and helping them organise the care of their children. The most frequent answer in the PPC group was the PPC team (93.3%), compared to a hospitalist in the non-PPC group (62.5%). However, we found that 25% of parents in the non-PPC group reported that nobody helped them organise the end-of-life care of their children.

End-of-life care and bereavement supportThe scores parents gave to their experiences in relation to the end-of-life care of the child were among the lowest in the 6 domains of quality of care in the non-PPC group (mean, 4.27; SD, 1.65) and the neonatal group (mean, 3.85; SD, 1.74) (Fig. 3). This was also reflected in the reported overall satisfaction, with a significantly lower level of satisfaction in parents in the non-PPC group (mean, 4.63; SD, 1.77) and in the neonatal group (mean, 4.43; SD, 1.73) compared to parents in the PPC group (mean, 6.00; SD, 0.00; P<.01).

All children managed by the PPC team died at home, accompanied by their parents and close relatives or friends. In the neonatal group, all newborns died in the neonatal intensive care unit, 30.4% of parents were not present when their children died, and only 34.8% of parents were accompanied by family or close friends.

In our sample, 67.4% of parents reported not using any form of bereavement support. Once again, the neonatal group was by far the group with the least access to support services, with 87% of the parents not receiving any form of support and only 8.7% receiving psychological care.

Positive and negative experiences with the care receivedParents described 3 positive and 3 negative experiences related to the end-of-life care of their children. We categorised their responses by domain of quality of care, and the results are summarised in Table 4. Positive experiences most frequently involved the support of the family: the humanity, commitment, empathy and warmth of care teams. The most negative experiences corresponded to the neonatal group and mostly involved bereavement support and the support of the family unit. When it came to bereavement, parents complained that they were not given time with their children after death, that they were not allowed to keep the cord clamp or the ID tags or any other memento, that they would have liked to perform some form of religious farewell ritual and that they did not receive any kind of psychological support. In the support of the family domain, negative experiences had to do with particular moments where the staff exhibited a lack of empathy or rapport, feeling alone facing the death of their children, the lack of privacy and only 1 family member being allowed to be with the child in the hospital.

Description of positive and negative experiences of parents in relation to the care received.

| Quality of care domain | PPCn=15 | Non-PPCn=8 | Neonataln=23 | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive experiences | ||||

| 1. Support of the family unit | 24 | 11 | 30 | We never felt alone. We had support and guidance daily, and they were always available to help us at any time (PPC). |

| 2. Communication | 0 | 0 | 10 | The positivity and hope inspired by the team (Neonatal). |

| 3. Shared decision-making | 1 | 0 | 0 | Always provided guidance on how to manage the disease (PPC). |

| 4. Relief of pain and other symptoms | 3 | 2 | 6 | Knowing that every possible measure was being taken to remove the pain (PPC). |

| 5. Continuity and coordination of care | 2 | 0 | 0 | The comfort, support and calm we experienced in always dealing with the PPC team and no longer dealing with strangers (PPC). |

| 6. Bereavement support | 2 | 0 | 1 | To be able to care for her and be with her until the end at home (CPP). |

| Negative experiences | ||||

| 1. Support of the family unit | 4 | 2 | 9 | Lack of privacy due to the small space shared with other parents and babies (Neonatal). |

| 2. Communication | 0 | 1 | 5 | Short time available to talk to paediatrician (Neonatal). |

| 3. Shared decision-making | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 4. Relief of pain and other symptoms | 2 | 1 | 0 | Having to negotiate administration of pain relief with nurses (Non-PPC) |

| 5. Continuity and coordination of care | 2 | 2 | 3 | Dreading weekends because the on-call physicians that came did not know my child (Non-PPC). |

| 6. Bereavement support | 0 | 2 | 13 | After my child died, they did not let us be with him. They took a long time to bring him back, and we had to say goodbye to him when he was shrouded, cold and blue (Neonatal). |

Some of the positive and negative experiences of parents were counted in more than one domain.

This is one of the few studies on the effectiveness of palliative care in children at the end of life and their parents. We assessed the effectiveness based on the perceptions of parents, which allowed us to learn about their experiences and their satisfaction with the care received.

Experiences vs. satisfaction with the care receivedThe purpose of asking parents about their satisfaction with the care received is to assess the quality of care.11 However, high levels of satisfaction may merely indicate low expectations on the part of parents, and thus should not be directly interpreted as evidence of high-quality care.11 A high level of satisfaction could simply indicate that there were no unexpected negative events. This was the case in the study conducted by Wolfe et al.,12 in which parents reported considerable suffering at the end of life in children with cancer at the same time as high levels of satisfaction with the care received. The assessment of personal experiences with specific aspects of care offers a more reliable picture of the quality of care that is less biased by parental expectations.7 In our study, the non-PPC group reported less positive experiences with the alleviation of pain and other symptoms, yet the satisfaction of parents in this domain was high (Fig. 3). This was also the case with shared decision-making, the domain in which parents in the non-PPC and neonatal groups reported the least positive experiences out of all 6, with which they nevertheless reported high satisfaction (Fig. 3).

Support to the family unitParents going through the death of a child have a strong need of compassionate professional support.7 The positive experiences described by parents most frequently involved the support received by the family: the humanity, commitment, understanding and warmth of the care staff. Some of the negative experiences described by parents also had to do with specific instances where the care team exhibited a lack of empathy or rapport with the family. Although this may only happen to a few families, we cannot take this experience lightly, as its negative repercussions could endure years after the incident.7

Communication with the health care teamParents consider straightforward, tactful, honest and clear communication essential,13–15 and the lack of information or communication are deficiencies in care delivery that are often identified in systematic reviews, such as those by Aschenbrenner et al.13 or Stevenson et al.15 In our study, the experiences and satisfaction of parents with the communication with the care team were very positive. Positive experiences predominated in the written comments of parents that involved this domain.

Shared decision-makingMany parents in our study considered that decisions regarding resuscitation and withdrawal or withholding of ineffective treatments were not made jointly by the care team and the family, but independently by the care team. These results were similar to those found in the PELICAN study,7 but contradicted the findings of previous studies on decision-making at the end of life in neonatology,16,17 which report shared decision-making of the care team and family regarding withdrawal or withholding of ineffective treatment in 84% and 92% of cases. Decision-making must pursue the best interests of the child and the family. However, health professionals and parents each have their own personal perceptions, values and interpretations of what is best for the child, and there is a power imbalance in this context.7 In light of these findings, we need to reflect, listen more attentively to families, address their needs and include parents in making important decisions for their children.

Relief of pain and other symptomsThe experience of parents in the alleviation of suffering was the most positive out of the 6 quality domains, and the levels of satisfaction with the care received in this domain were also very high. The experiences related to pain relief received some of the lowest scores given by parents in the non-PPC group although, as we already noted, the satisfaction of these parents with the care received in this domain was high.

Continuity and coordination of careHaving a specific member of the care team in charge of coordinating end-of-life care for the child and as a stable point-of-contact for the family was one of the most important needs identified by parents in our study. The continuity and coordination of care have been identified as important factors in promoting parental involvement in the care of their children, reducing frustration and improving confidence in the quality of care.18 In our study, experiences relating to the continuity and coordination of care received the second highest ratings out of the 6 domains of care. However, the level of satisfaction in this domain was lowest in the non-PPC group, with 25% of parents expressing that they had no help organising the end-of-life care for their children. In the description of negative experiences, one mother in the non-PPC group specifically stated that they were alone in the end-of-life process. Our findings support previous evidence that home care is a key factor in giving parents confidence and reassurance at the end of life of the child. In their description of positive experiences, parents in the PPC group praised the continuity of care offered by the PPC team: they were thankful that they were never alone and that they always dealt with the same providers regardless of setting, and not only in their home.

End-of-life care and bereavement supportThe domain corresponding to the least positive experiences and the lowest satisfaction in the non-PPC and neonatal groups was the care at the end of life and bereavement support. The involvement of the PPC team significantly improved both the experiences and the satisfaction of parents (P<.05). The health care staff should have specific training in PPC, end-of-life care and bereavement support to understand and address the needs of parents at the end of life of their children.

After the death of a child, the care must continue with the provision of bereavement support to parents. In the description of their experiences and the support services that they accessed, parents expressed their wish for psychological support in the grieving process and to meet other parents that have experienced the loss of a child.

Limitations of the studyThe main limitation of our study is the small sample size (N=46 parents), on account of which the findings may not be generalisable to the rest of the population of bereaved parents in the Region of Murcia. Of all the families we got in touch with, 85.9% agreed to participate in the study, but only 43.8% of those eligible families we were able to reach ultimately completed the questionnaire (Fig. 1). This may be a source of selection bias, as it is possible only families that felt very thankful and satisfied with the care felt sufficiently motivated to complete the questionnaire. This could also explain the favourable results we found both in the reported experiences and levels of satisfaction.

ConclusionsOur study shows that parents had positive experiences and a high satisfaction with the end-of-life care of their children. However, while the overall results were favourable, we found differences both in the experiences and the satisfaction of parents based on the health care team that managed the end-of-life care of the child. Parents of children managed by the PPC team had the most positive experiences and the highest levels of satisfaction in the 6 domains of quality of care under study, with significantly higher scores in the domains of support of the family unit, shared decision-making and bereavement support (P<.05).

In our practice as paediatricians, those of us that manage children with life-threatening or life-limiting diseases but are not specialised in palliative care should improve our knowledge on palliative care, symptom relief, communication, end-of-life care and bereavement support. We must address the physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs of children and their families, and make sure that parents are given the opportunity to participate in decision-making and care delivery at the end of their children's lives.

Involvement of the PPC team improves the quality of end-of-life care in the paediatric population in the Region of Murcia. Its support, empathy, commitment, humanity and warmth towards families combined with its expertise in symptom relief are essential to parents facing the death of a child.

Multicentre studies with larger samples are required to confirm the results of this study and to optimise the end-of-life care offered to paediatric patients and their families.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank all participating parents for their collaboration and their willingness to recall difficult times in their lives. We also thank the PPC unit of the HCUVA for its daily work and their support to our paediatric patients and their families, and Julio Sánchez Meca for his help in the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Plaza Fornieles M, García-Marcos Barbero P, Galera Miñarro AM, Barbieri G, Bellavia N, Bermúdez Cortés MDM, et al. Eficacia del Equipo de Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos de Murcia según la experiencia de los padres. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:4–15.