Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy poses a significant challenge to the public health system and in the management of blood cancers. The article “Immunotherapy with CAR T-cells in paediatric haematology-oncology”1 by the Group on Immunotherapy and Advanced Therapies of the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology) provides an interesting review of the most relevant aspects of the introduction of immunotherapy with T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) in the therapeutic armamentarium against CD19+ B cell lymphoproliferative disorders.

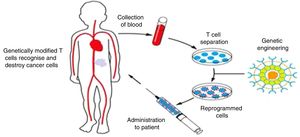

CAR T-cells are T cells that have been genetically engineered to express a receptor that targets a tumour antigen. Thus, the CAR T cell can attack and destroy the tumour cell without the mediation of the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) complex (Fig. 1). CAR T-cells that target the B-lymphocyte antigen CD19 (CART-19) can eliminate tumour cells in B-cell lymphomas and leukaemias. It is precisely in paediatric patients with very advanced B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and few therapeutic options that CAR T-cells have proven most efficacious. And it was an international clinical trial, with participation of a Spanish hospital, in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, that led to the marketing authorisation of tisagenlecleucel, one of the existing commercial CAR T-cell products.2 In Spain, CART-19 therapies are also developed in the academic setting,3 and there is a phase I clinical trial underway in adult and paediatric patients the results of which are to be published soon.

Production and delivery of CAR T cells. Lymphocytes are harvested from the patient by means of leukapheresis. Ex vivo, T cells are separated, expanded and genetically modified to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that recognises a tumour antigen (CD19 in the case of CART-19), and then are infused back into the patient.

The authorisation by regulatory agencies of tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel (the 2 commercial CD19-targeting CAR T-cell products manufactured for treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults and diffuse large B cell lymphoma in adults) motivated the development and implementation of the National Plan for Advanced Therapies-CAR T-cell therapies in Spain. This plan not only underscored the importance of identifying the best-suited facilities for the administration of these therapies, but placed particular emphasis on the need for restructuring in some of these hospitals so that in-house manufacturing of this type of individualised immunotherapies can be integrated in their care delivery. Hospitals specialised in paediatric haematology and oncology thus face the challenge of evolving towards a care delivery model that includes this gene and cellular therapy, aiming to develop the capacity to manage every aspect involved in the use, manufacture and administration of these novel treatments in house. In this regard, the development in Spain of an academic CAR T-cell therapy and a clinical trial with adult and paediatric patients has proven the viability of this type of therapy in our country.3

In addition to describing what CAR T-cells are, how they work and the importance of understanding their clinical performance, the article delves into aspects that are essential for their use in clinical practice. One of the most specific aspects addressed in the article is the essential need for the collaboration and coordination of multiple hospital-based care specialities, a concept comprehended in what the authors refer to as multidisciplinary CAR T-cell team. While the list may seem long (haematologists, immunologists, intensive care specialists, paediatricians, neurologists, oncologists, biologists, pharmacologists, hospital pharmacists, experts in regulation and quality assurance systems, nurses, etc.), more than 1 year after the introduction of this management approach it has become evident that all of these actors are essential to provide effective and efficient care to patients.

The article also addresses the option of direct in-house (“academic”) manufacturing and management of these therapeutic approaches, in which there is a vast opportunity for ongoing improvement that should be realised. The current regulation on medicinal products seeks to stabilise production systems, but as is the case with most gene and cellular therapies, CAR T-cell therapies require rapid adaptation to offer the most beneficial treatment options. It is important to establish mechanisms for the introduction of improvements (which are nearly limitless in advanced therapies), and optimisation of cellular therapy can only occur if manufacturing and trials are feasible in academic settings. Therefore, it is important to equip hospitals with the necessary human and material resources and to develop more specific regulation that rather than obstruct will allow this “manufacture and development” of academic projects that will open access to new CAR-based immunotherapies. The academic setting allows a more agile honing and innovation of CARs, implementation of new protocols for manufacture and management and definition of specific clinical strategies that will more rapidly and conclusively identify the most efficacious therapeutic options for patients. In addition, it can conduct research on CARs for treatment of less prevalent diseases, such as cancer in the paediatric age group, in which the pharmaceutical industry may have less interest.

Last of all, aside from any economic considerations regarding CAR T-cell therapy that could have a negative impact in universal public health systems like the one in Spain, “bedside” biopharmaceutical development offers other important advantages. On one hand, it facilitates management of the treatment process, as in-house manufacture of CAR T-cells can reduce production times, an essential factor in patients with advanced cancer. It also reduces the carbon footprint compared to commercial CAR T-cell products as it cuts the CO2 emissions resulting from the transport of cells between the prescribing hospital and the commercial manufacturing facility, which may be separated by thousands of kilometres. On the other hand, local manufacture can also be important in the context of crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, which is currently putting many oncological patients at extreme risk.4 Long-distance connection and communication difficulties place a significant strain on care delivery through a host of different problems, including supply shortages when products are manufactured far from the patient. Decentralised in-house processes, such as academic CAR T-cell projects, offer a flexibility that, in the context of a crisis like the one we are currently facing, could and should facilitate access to these therapies that are used as a last resort in patients facing a life-or-death situation, which obviously has unique connotations when it comes to paediatric patients.

CAR T-cells constitute a revolutionary and highly significant advance in the treatment of some blood cancers. Research can identify new targets and mechanisms to combat the significant barriers that currently hinder their use in other types of solid tumours and could open up a new approach to the treatment of cancer and possibly other disorders, such as autoimmune diseases. The constitution of an immunotherapy group in the framework of the Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica is a very significant step towards ensuring rapid access to these therapies for paediatric patients.

This editorial is included as a work sponsored by grants PI18/000775 and AC18/00072 (CE_ERA Net_Nanomed18) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III with Fondos FEDER - "Una manera de hacer Europa".. This work is also funded by the "Fundacio bancaria la Caixa" (3922-19 FCRB).

Please cite this article as: Juan M, Rives S. Inmunoterapia CAR-T en hemato-oncología pediátrica… presente y futuro. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:1–3.