The percentage of difficult intravenous access cases is high in pediatric care, and multiple attempts may be needed to establish peripheral venous access. The DIVA score allows identification of these patients; however, a validated version of this tool is not yet available in Spain. The objective of this study was to develop the Spanish version of the DIVA score.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study with psychometric analysis in two phases: adaptation of the DIVA score to Spanish and analysis of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version (DIVA-SP).

The first phase consisted in the forward and back translation and back-translation of the score followed by expert evaluation and pretesting to develop the DIVA-SP. In the second phase, the scale was validated in a sample of patients aged up to 16 years admitted to different departments of a tertiary care hospital who required peripheral venous access. The nurse in charge of the patient completed the scale, which was included in an ad-hoc questionnaire along with other items to collect sociodemographic data.

ResultsA total of 353 catheterizations were included. All items exhibited reliability with kappa values greater than 0.61. In the analysis of robustness, all items were deemed adequate except the history of prematurity. For the three-variable model, a cut-off point of 4 in the DIVA score showed a sensitivity of 0.45, a specificity of 0.81, a positive predictive value of 0.64, a negative predictive value of 0.67, a positive likelihood ratio of 2.44 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.67. Of all patients, 66% were classified correctly and 33% incorrectly.

ConclusionsThe DIVA-SP is useful, valid and reliable for application in Spain. Furthermore, it exhibits better psychometric properties than the original version for identifying difficult intravenous access in pediatric patients.

El porcentaje de vías venosas difíciles en pediatría es elevado, lo que requiere múltiples intentos para canalizar un acceso venoso periférico. La DIVA Score permite identificar a estos pacientes; sin embargo, en España no se dispone de una versión válida de esta herramienta. El objetivo de este estudio fue obtener la versión española de la escala DIVA Score.

Material, pacientes y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal de carácter métrico desarrollado en dos etapas: adaptación al español de la DIVA Score y análisis de las propiedades métricas de la escala en su versión española (DIVA Score-SP).

En la primera fase se siguió un proceso de traducción, retrotraducción, evaluación por expertos y pre-test hasta conseguir la DIVA Score-SP. En la segunda fase, se validó la escala incluyendo a pacientes de hasta los 16 años ingresados en distintas áreas de un hospital de tercer nivel que precisaron acceso venoso periférico. La enfermera responsable cumplimentaba la escala, incluida en un cuestionario ad-hoc, junto con otros datos sociodemográficos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 353 canalizaciones. Todos los ítems mostraron una fiabilidad con valores de kappa>0.61. En el análisis de la robustez, todos los ítems resultaron adecuados, excepto el ítem “antecedentes de prematuridad”. Para el modelo de tres variables, el punto de corte DIVA Score≥4 mostró: sensibilidad = 0,45, especificidad = 0,81, VPP = 0,64, VPN = 0,67, LR(+) = 2,44 y LR(-) = 0,67. Se clasificaron correctamente el 66% de los pacientes e incorrectamente el 33%.

ConclusionesLa DIVA Score-SP es útil, válida y fiable en nuestro contexto. Además, presenta mejores propiedades instrumentales que la versión original para identificar vías venosas difíciles en pediatría.

Peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) placement is one of the most frequently performed invasive procedures in pediatric inpatients, and it is estimated that about 50% of hospitalized children require this technique.1,2

However, establishing peripheral intravenous access is not always easy and often requires multiple attempts. The success rate of PIVC insertion on the first attempt in pediatric patients ranges between 46% and 76%, decreasing to as little as 33% in infants.3–5 This situation is referred to as difficult venous access (DVA) or difficult intravenous access (DIVA). According to Bahl et al.,6 DIVA is defined as two or more failed attempts using conventional methods, suggestive physical examination findings (no visible or palpable veins) or a previous history of DIVA.

Pain is one of the consequences of multiple venipunctures.7 Children who experience frequent painful events develop an increased sensitivity to pain and maladaptive responses, which affect cognitive and motor development.8 They also tend to develop needle phobia, which causes anticipatory anxiety that may persist to adulthood, complicating subsequent health care encounters. These effects also affect the family and health care workers, who experience the inevitable procedure with the same intensity, anxiety and frustration.8,9 On the other hand, multiple insertion attempts delay diagnosis or initiation of treatment, reduce the number of available access sites in the patient and cause complications such as infection or extravasation, increasing the length of stay and, therefore, costs.10,11

In light of the above, the use of imaging techniques is recommended to reduce the proportion of failed PIVC insertion attempts.12–16 Some authors suggest the use of clinical prediction rules and algorithms to facilitate decision-making in patients with difficult venous access.17–19 Yen et al. developed the Difficult Intravenous Access Score (DIVA Score)20 to identify patients with difficult venous access, which is composed of four variables: vein visible after tourniquet (not visible = 2 points, visible = 0 points), vein palpable after tourniquet (not palpable = 2 points, palpable = 0 points), age category (>1 year = 3 points; 12 years = 1 point; ≥3 years = 0 points) and history of prematurity (gestational age < 38 weeks = 3 points; ≥38 weeks = 0 points). The possible score ranges from 0 to 10, and a score of 4 points of higher is indicative of a 50% chance of failure on the first attempt. Later on, external validation studies were conducted in different English-speaking locations,21,22 modified versions were proposed and validated23–25 and the scale was translated and adapted for use in Brazil26 and also adapted for the adult population.27

In 2019, a study conducted in Spain found a first-attempt success rate for PIVC insertion of only 38%.28 The use of technologies to guide catheter insertion is growing with the aim of avoiding failed attempts, given their many negative effects.12–16 However, in our region, a tool allowing prediction of the probability of failure in PIVC insertion is still not available, so there is a need to carry out and validate the cross-cultural adaptation of the DIVA Score in the Spanish population. Thus, the general objective of our study was to produce the Spanish version of the DIVA Score. The specific objectives were the translation to Spanish and cultural adaptation to the Spanish population of the score, followed by assessment of its psychometric properties.

Material and methodsStudy designCross-sectional descriptive and quantitative study conducted in two phases: Spanish translation and adaptation of the DIVA Score and analysis of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the scale (DIVA Score-SP).

We conducted the Spanish translation and adaptation of the instrument following the recommendations of the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR)29 and of Beaton et al.30 The second phase, for validating the Spanish version of the scale, was carried out from January to October 2021 in different pediatric care settings at the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid: the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), the pediatric emergency department (PED) and the general pediatrics and infant ward.

SampleFor the purpose of content validation in the first phase, we selected 30 nurses from the pediatric care settings included in the study. To be eligible, they had to have a minimum of two years’ experience in the hospital’s department of pediatrics.

For the second phase, the validity and reliability assessment, we recruited patients aged 0 to 16 years who either visited the pediatric emergency department or were hospitalized in the general pediatrics ward, infant ward or pediatric intensive care unit during the study period and who required PIVC insertion. We excluded patients with life-threatening emergencies, those for whom we were unable to obtain consent and patients with less than 80% of the questionnaire completed or any missing items in the DIVA Score.

Study phasesFirst phase: translation and cross-cultural adaptation

- a

Before the translation: We contacted the author of the original scale, who in addition to giving permission for the translation, also agreed to participate in its adaptation.

- b

Translation process: We engaged two bilingual translators who were native Spanish speakers, one of whom had specialized health care knowledge and one who did not. Both translators produced translations independently and then, with the collaboration of the research team, synthesized both Spanish versions into a single version (DIVA Score-SP0.0).

- c

Backward translation: Subsequently, two bilingual translators who were native English speakers independently translated the Spanish version (DIVA Score-SP0.0) back to English, after which both back-translated versions were synthesized into one (DIVA Score-SP1.0).

- d

Expert evaluation: Following the recommendations of the COSMIN checklist,31 we carried out a conventional Delphi process with participation of four translators, one bilingual linguist, four nurses proficient in English and with a minimum of 5 years of experience in pediatric care, a doctor in health care research methodology proficient in English and the author of the scale. We created an online questionnaire that was submitted to the participants, who evaluated the semantic and conceptual equivalence on a Likert scale (none, poor, good, excellent). Items with negative ratings and/or suggestions were revised. Lastly, the final consolidation was performed with the help of an expert in the Spanish language, giving rise to the DIVA Score-SP2.0 version. After producing a report detailing the modifications, a second round was conducted, which did not yield further contributions.

- e

Pretest of the translated questionnaire: an ad hoc questionnaire was administered to 30 pediatric nurses working a tertiary care hospital. The questionnaire included a section to collect data on the sociodemographic characteristic of the nurses (age, sex, experience in pediatric care, care setting where they were currently working) and the DIVA Score-SP2.0 version, translated and adapted for the Spanish population. Nurses rated the items of the instrument on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 in relation to their comprehensibility and pertinence, in addition to rating the utility and simplicity of the instrument. Subsequently, they applied the tourniquet on the extremity to undergo venipuncture, performing a naked-eye examination of the venous anatomy of the patient, without actually performing the insertion. Lastly, they completed the instrument and recorded the time it took them to apply it. A single stopwatch was used for this purpose in every case, starting at the time the nurse started to read the heading of the DIVA Score form and ending when the total score was written down. After making small modifications to the format, the final version (DIVA Score-SP3.0; Appendix B, Supplemental material) was complete.

After the examination of the venous anatomy after applying a tourniquet, the most suitable vessel for cannulation was selected and, before puncture, the provider completed the DIVA Score-SP3.0. To assess interrater reliability, a second nurse made an independent assessment of the selected vase and also completed the instrument. This assessment was conducted in 10 patients per item (for a total of 40 pairs of observations).32,33

Study variablesFor the assessment of construct validity, we developed an ad hoc questionnaire (Supplemental material) to collect data on different variables grouped into four sections: (a) nurse-related: age, sex, experience in pediatric care, work setting; (b) patient-related: age, sex, weight; (c) procedure-related: success on first attempt (when possible, administering 2 mL of physiological saline without observing signs of extravasation), total attempts, desisting from PIVC insertion; and (d) instrument-related: items of the scale, score.

Sample sizeWe recruited participants through nonrandomized consecutive sampling, calculating the necessary sample size based on the 25% first-attempt failure rate reported by Yen et al.20 Taking as reference the population of 59 621 patients who visited the PED and were admitted to the two inpatient settings specified above, we estimated we needed a sample of a minimum of 287 participants for a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 5%. Assuming losses of 20%, we settled on a final sample of 360 patients requiring PIVC placement. Although we did not perform formal stratification by age group or health care conditions, we considered several factors to minimize potential biases in the distribution of patients. We took into account the larger proportion of patients managed at the PED, the frequency of cannulation and medical complexity. We also ascertained that the number of admissions was similar for the ward and the PICU, guaranteeing a balanced and representative sample distribution.

Statistical analysisWe described qualitative variables in terms of frequences and percentages and quantitative variables in terms of the median and interquartile range, as the data did not follow a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Qualitative data were compared by means of the χ2 or Fisher exact test and quantitative data using the Student t or Mann-Whitney U test. In the assessment of reliability, given the nature of the scale, we assessed interrater reliability by means of the Cohen kappa, considering agreement good from a kappa value of 0.61.34 In the assessment of feasibility, we studied the time it took nurses to apply the score in the pretest study. In the validity assessment, we evaluated logical validity by analyzing the response rate to the items during the pretest and the perceived utility of the scale. To assess content validity, we analyzed the opinion of nurses regarding the comprehensibility, relevance, utility and simplicity of the test with the Lawshe method. We calculated the content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI), considering values of 0.33 and 0.80 or greater, respectively, indicative of an adequate content validity for the total scale.35,36 We evaluated predictive validity by means of multivariate logistic regression, using failure in the first attempt as the reference, assessing model robustness by means of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the area under the curve (AUC) obtained in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed by calculating the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR + and LR−).37 We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The data were processed and analyzed with Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS version 29.0. Cases for which the full instrument was not completed, were excluded from the analysis, and missing data in other parts of the questionnaire were not handled in any way, as they did not affect the variables of interest.

ResultsTranslation and cross-cultural adaptationForward and backward translation: after two rounds, the minor discrepancies between the versions of the four translators were remedied, achieving 100% agreement in the final version.

Semantic and conceptual equivalence assessment: the group of experts rated each of the items positively with the exception of the “rango de edad” (age category) item, for which there was disagreement regarding conceptual equivalence. The percent believed there was no equivalence and 20% that the equivalence was “poor”. In the new Spanish version, the age categories do not correspond to those in the original scale. The issue was resolved by leaving only the numerical values for each age range, removing the words used to label each category in the English version. In the second round, no other modifications were suggested, and there was unanimous agreement on the item.

Pretest: the study questionnaire was completed by 30 nurses, 86% (n = 26) female, with a mean (SD) age of 38 (6.9) years and a median experience in pediatric care of 12 [5.7–15.0] years.

Fig. 1 summarizes the opinions regarding the comprehensibility and relevance of each item, the title and the explanation at the foot of the table, as well as the utility and simplicity.

At this point, modifications were made to both the explanation at the foot of the table and the structural format of the instrument. In addition, directions were drafted to guide the completion of the score (Appendix B, Supplemental material).

Reliability: the two groups of nurses that applied the score (observer 1 and observer 2) had similar characteristics (Table 1). The agreement in all item scores and the total score were above the required kappa value threshold of 0.68 (Table 2).

Sociodemographic characteristics of observers and patients in the interrater reliability assessment of the DIVA Score.

| Variables | Test nurses (observer 1) n = 40 | Control nurses (observer 2) n = 40 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)b | 37.5 [34−47] | 37 [34.2−41] | .515 |

| Sexa | |||

| Male | 3 (7.5) | 9 (22.5) | .060 |

| Female | 37 (92.5) | 32 (77.5) | |

| Settinga | |||

| PED | 8 (20) | 8 (20) | .937 |

| PICU | 28 (70) | 27 (67.5) | |

| Pediatrics ward | 4 (10) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Years of experience in pediatric careb | 9.5 [3−17.7] | 11.5 5–15 | .809 |

Abbreviations: DIVA: difficult intravenous access; PED: pediatric emergency department; PICU: pediatric intensive care unit.

Interrater reliability: DIVA Score-SP.

| Item | Cohen kappa | P |

|---|---|---|

| Vena visible tras la aplicación de un torniquete (vein visible after tourniquet) | 0.79 | <.001 |

| Vena palpable tras la aplicación de un torniquete (vein palpable after tourniquet) | 0.68 | <.001 |

| Rango de edad (age category) | 1 | <.001 |

| Antecedentes de prematuridad (history of prematurity) | 0.93 | <.001 |

| DIVA Score-SP | 0.78 | <.001 |

The analysis included 30 pairs of measurements.

Abbreviation: DIVA Score-SP, Difficult Intravenous Access Score-Spanish version.

Feasibility: the mean (SD) completion time was 32.2 (13.8) seconds. Of the total nurses, 73.3% (n = 22) strongly agreed that the scale was easy to use, and there were no negative ratings (Fig. 1).

ValidityLogical validity: all items were completed in every instance save for the history of prematurity, which was not completed by two nurses. As regards the utility of the scale, 93.3% of ratings were positive (Fig. 1).

Content validity: none of the items had a CVR of less than 0.33. The CVI was of 0.84 (Table 3).

Content validity: DIVA Score-SP.

| Item | CVR | CVR | CVI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Comprehensibility | ||

| Title | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| Vena visible tras la aplicación de un torniquete (vein visible after tourniquet) | 0.87 | 0.87 | |

| Vena palpable tras la aplicación de un torniquete (vein palpable after tourniquet) | 0.87 | 0.87 | |

| Rango de edad (age category) | 0.93 | 0.87 | |

| Antecedentes de prematuridad (history of prematurity) | 0.53 | 0.87 | |

| Explanations at foot of table | 0.93 | 0.80 |

Abbreviations: CVI, content validity index; CVR, content validity ratio; DIVA Score-SP, Difficult Intravenous Access Score-Spanish version.

Criterion validity (predictive): out of 366 catheter insertions, 13 were excluded due to the lack of completion of the history of prematurity item, leaving a total of 353. Most nurses that performed the technique were female (69.1%; n = 244), and more than half worked in the PED (55.5%; n = 196). Patients aged less than 2 years were the largest age category (54.4%; n = 192) (Table 4). The first attempt failed in 41.9% (n = 148) of the 353 patients, and the team chose to desist in achieving PIVC insertion after one or several failed attempts in 54 patients. A single attempt was made in 62% patients (n = 220), which was successful in 205 cases and failed in 15 cases in which the decision was made not to pursue further attempts. In 20.7% of the patients (n = 73) two attempts were made, and in 17% (n = 60) three or more attempts, with two patients undergoing a total of seven attempts. The decision to desist was made after the first attempt in 15 patients, after the second attempt in 17, after the third attempt in 10, after the fourth attempt in five, after the fifth attempt in three, after the sixth attempt in three and after the seventh in one. The median DIVA Score was 3 [1–5] points. In the analysis of robustness, all the items were statistically significant with the exception of the history of prematurity (Table 5).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the nurses who applied the DIVA Score to patients and characteristics of patients assessed with this scale (predictive validity).

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Attempts by nurse | N = 353 (100%) |

| Nurse age (years)b | 41 [34−44] |

| Nurse sexa | |

| Female | 244 (69.1) |

| Care settinga | |

| PED | 196 (55.5) |

| PICU | 102 (28.9) |

| Ward | 55 (15.6) |

| Years of experience in pediatric careb | 11.9 4–15 |

| Patients | n = 353 (100%) |

| Age categorya | |

| Neonate (0−29 days) | 7 (2) |

| Young infant (1−12 months) | 105 (29.7) |

| Old infant (1−2 years) | 80 (22.7) |

| Preschooler (2−5 years) | 53 (15) |

| School-aged child (6−11 years) | 60 (17) |

| Adolescent (12−16 years) | 45 (127) |

| Patient sexa | |

| Male | 202 (57.2) |

Abbreviations: DIVA, difficult intravenous access; PED, pediatric emergency department; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Multivariate analysis of the final version of the DIVA Score-SP.

| Variables | n (%) | B (β) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 353) | ||||

| Vena visible tras la aplicación de un torniquete (visible vein)a | ||||

| Visible | 244 (69.1) | – | – | – |

| Not visible | 109 (30.9) | 0.76 | 2.1 (1.28−3.62) | < .001 |

| Vena palpable tras la aplicación de un torniquete (palpable vein)a | ||||

| Palpable | 211 (59.8) | – | – | – |

| Not palpable | 142 (40.2) | 0.71 | 2 (1.28−3.32) | < .001 |

| Rango de edad (age category)a | ||||

| ≥ 3 years | 161 (45.6) | – | – | – |

| 1−2 years | 76 (21.5) | 1.03 | 2.8 (1.56−5.09) | < .001 |

| < 1 years | 116 (32.9) | 1.52 | 4.6 (2.64−8.03) | < .001 |

| Antecedentes de prematuridad (history of prematurity)a | ||||

| Premature | 36 (10.2) | 0.21 | 1.23 (0.58−2.60) | .574 |

| Not premature | 317 (89.8) | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DIVA Score-SP, Difficult Intravenous Access Score-Spanish version; OR, odds ratio.

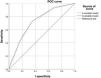

The three-variable model (removing the history of prematurity item) behaved similarly to the four-variable model (ROC AUC, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.67−0.77] vs 0.72 [95% CI, 0.67−0.78]) (Fig. 2). Using the same scoring system of the original instrument for the three-model variable, a DIVA Score of 4 points or greater exhibited a sensitivity of 0.45 and a specificity of 0.81, with a PPV of 0.64, a NPV of 0.67, a LR+ of 2.44 and a LR− of 0.67 (Table 6). The score classified 66% of patients correctly and 33% incorrectly.

Predictive characteristics based on DIVA Score-SP (final version).

| Failure on first attempt | Total | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | LR+ | NPV | LR− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||||

| Score on DIVA Score-SP | |||||||||

| 0 | 11 | 68 | 79 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 0.93 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.39 | 0.86 | 0.22 |

| 2 | 22 | 50 | 72 | 0.87 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 1.46 | 0.81 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 40 | 34 | 74 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 2.06 | 0.76 | 0.42 |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 2.44 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 5 | 54 | 30 | 84 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 2.60 | 0.66 | 0.69 |

| 7 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.59 | 0.94 |

| Total | 148 | 205 | 353 |

Abbreviations: DIVA Score-SP, Difficult Intravenous Access Score-Spanish version; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

The final DIVA Score-SP is a simple instrument for clinical practice that is useful, valid and reliable.

Validation methodologyIn this case, we applied it to the Spanish translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the DIVA Score. We ought to highlight that this validation study was the most systematic and thorough in respect of current recommendations.29,30 Generally, the studies we identified in the literature conducted to apply this scale in other countries did not carry out the full process and only assessed predictive validity after a plain and literal translation of the items. Only two studies aimed to apply the full forward translation, backward translation and adaptation process, although the subsequent analysis of the psychometric properties of the instrument was limited.

The study conducted in Turkey by Gerçeker et al.38 involved five translators and a single language expert to do the backward translation. The sample included only 90 children. The group of experts did not carry out an assessment of the semantic and conceptual equivalence of the translated version, nor a pretest. Internal consistency was evaluated by means of the Cronbach α, which was not sufficiently rigorous, since the items could have either two or three possible options. Therefore, caution should be exerted in interpreting these results. With regard to test-retest reliability, the analysis included repeated measures taken two weeks apart in a subset of 30 patients. Since the clinical condition of patients can change considerably, even in a matter of hours,37 we do not consider this appropriate. For these reasons, in our study we considered that it would be more appropriate and robust to limit the analysis to interrater reliability. The authors of the Turkish study also decided to eliminate the item assessing skin shade, as did the author of the original instrument. There was no analysis of predictive validity, although they did analyze content validity with the help of 10 experts. The authors concluded that the instrument was valid, feasible, simple and quick.

In the study conducted by Freire et al.26 to translate the instrument to Portuguese and adapt it to the Brazilian population, the steps taken included forward and backward translation with a similar approach to the one used in our study. A group of experts also evaluated the semantic and conceptual equivalence of the instrument and a pretest study was conducted. However, they selected 20 health care workers (physicians, nurses and nurse technicians) and applied the scale to 30 children. In our study, 30 different nurses applied the instrument to 30 pediatric patients. In the Brazilian study, the psychometric analysis was limited to the assessment of the reliability of the professionals’ opinions regarding the clarity of the translated items by means of the Cronbach α, which was not the most appropriate measure for the purpose, as it was intended to assess content validity.35,36 The authors concluded that the instrument was useful and easy to use for phlebotomists.

ReliabilityBased on the Cohen kappa values, the instrument, applied by pairs of providers in single patients, appeared to good reliability, with reproducible results.32 Items assessing more objective characteristics, such as age and the history of prematurity, had, as expected, higher scores indicative of very good reproducibility.

The authors of the original scale analyzed the reproducibility for several items that they considered subjective, but not for the total scale. Compared to our study, they found poorer agreement, although still acceptable, for the items “vein visible after tourniquet” and “vein palpable after tourniquet”, with kappa values of 0.61 and 0.57, respectively.20 This was similar to what has been described in a previous study, with kappa values of 0.51 and 0.43 for the same items.21

FeasibilityMost nurses considered the scale to be simple and quick to complete, making its implementation feasible.

Logical validityDuring the pretest, the response rate was perfect for all items except the history of prematurity, which was not completed in two instances because the nurses were unsure of how to answer it. This item requires consulting the health records, which can complicate the application of the scale or lead to arbitrary answers.

Most nurses considered the instrument useful for everyday clinical practice, although one experienced nurse did not find it useful. Previous studies have demonstrated that clinical judgment is not sufficiently reliable in predicting difficult intravenous access due to its variability, as it may depend on experience and the latter may be influenced by a variety of factors, so that it is not easily reproducible among providers.23 Specifically, Yen et al.20 found limited reliability in difficulty prediction among nurses (kappa value of 0.37). In the study conducted by O’Neill et al.,22 although it was doctors that performed catheter placement, they also described the instrument as user-friendly and useful for objective assessment of DIVA.

Content validityThe nurses surveyed in the pretest considered all items relevant and representative of the construct, except for the history of prematurity, which, while exceeding the established threshold, received a lower rating and was considered less relevant.

Criterion validity (predictive)The proportion of failures in first attempts of PIVC insertion was high, especially in infants aged less than one year. This could be due to the inclusion of patient from different hospital settings (ward, PED and PICU), however, other studies focused exclusively on the emergency care setting. Therefore, it is possible that patients in our study were more likely to have chronic conditions, affecting the success rate of cannulation attempts.10 In addition, 32.9% of the children were infants under one year. According to Lininger et al.,4 the proportion of failure increased to up to 66% in infants. Riker et al.21 found a proportion of failed first attempts of 32.2% in a sample with 23.2% of patients aged less than one year. Yen et al.20 reported a lower percentage (25%) in a sample with 13% of infants. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the “history of prematurity” item could be eliminated from the model, as was also reported by Riker et al.21 and Girotto et al.,23 which could be explained by the low proportion of children with such a history in the sample, as was the case in our study (10.2%). The ROC AUCs in both models (with and without this item) were similar, which suggests that it could be removed from the scale. Riker et al.21 reported an AUC of 0.720 (95% CI, 0.67−0.78), greater compared to the areas reported by Girotto et al.23 (AUC, 0.649; 95% CI, 0.589−0.709) and Yen et al.20 (AUC, 0.670). A study conducted in pediatric inpatients in a general care unit compared both models, finding that, although with a lower value compared to the studies mentioned above, the AUC was better for three-variable model (AUC, 0.620) compared to the four-variable model.24 In our study, due to the high prevalence of difficult intravenous access, the score had a better specificity and PPV, although with a lower sensitivity. However, the LR+ and LR− indicate that the probability of a positive result in the DIVA Score-SP is 2.44 times greater in patients with DIVA while the probability of a negative result is 1.5 times greater in patients without DIVA. These likelihood ratios correspond to a moderate impact in terms of clinical utility.39 In addition, the score classified 33% of children incorrectly. The low sensitivity of the instrument results in an increased probability of false negatives, which limits its usefulness for ruling out the problem. This means that some patients with DIVA may go undetected. Notwithstanding, the score could be useful as an initial screening tool if efficiency in terms of time and resources is prioritized, as it generates few false positives. In agreement with other authors, we recommend further efforts to enhance the psychometric properties of the scale and its external validity. Subsequently, it would be necessary to investigate whether the inclusion of the scale in clinical protocols achieved a decrease in the proportion of DIVA.

LimitationsSampling was consecutive and nonrandomized. Due to the nature of the instrument, which was composed of nonhomogeneous mixed variables, we were unable to assess internal consistency nor did assess test-retest reliability, as the changing clinical condition of patients could have affected the scores obtained with the scale. Although the scale was validated in different pediatric inpatient settings, we did not include the neonatal unit and the study was conducted in a single hospital, so the results need to be compared to results in other centers and care settings to be able to generalize them. Nevertheless, this study is the first to provide a valid tool for predicting DIVA in pediatric care settings in Spain.

ConclusionsThe DIVA Score-SP is useful, valid and reliable in our population, and offers certain improvements with respect to the original version of the instrument. However, its psychometric properties are limited (low sensitivity and a 33% error rate), so, as other authors before us, we recommend continuing the process of improving the scale and its external validation to confirm its predictive utility. Later on, it would be useful to analyze whether the inclusion of this scale in clinical pathways reduces the percentage of difficult intravenous access.

Ethical considerationsThe study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Law on Biomedical Research and good clinical practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the competent research ethics committee (TP/0279). Participation was voluntary and required prior signed informed consent from the parents. The study was conducted safeguarding the confidentiality and anonymity of participants.

Author contributionsAll authors agreed on the final version of the manuscript unanimously and contributed to both the concept and/or design of the study, the acquisition and/or analysis of data and, subsequently, the drafting and/or reviewing of the manuscript.

FundingThe first author, María de la Vieja, received a grant from the program for increasing research activity in the field of nursing of the Hospital 12 de Octubre (2020–2021 period).

The authors declare having no financial relationships that could give rise to a potential conflict of interest.

We want to express our most heartfelt thanks to the entire nursing team of the PICU, emergency department and ninth floor of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, thanks to whose collaboration and support we were able to carry out this study. We also thank all the experts that participated in the validation of the scale.

Special thanks to Dr Paloma Posada Moreno, who has played an important role in the development of the research project as well as the interpretation of the data to produce the DIVA Score-SP. We would also like to thank Ms Leticia Peláez-Rodríguez for the key role she played throughout the fieldwork and her contributions to the manuscript. Finally, we would like to thank Mr Julio Alberto Mateos Arroyo for reviewing the manuscript, giving us a new perspective on the methods and statistical analysis section. Due to the maximum number of authors allowed in the journal, it was not possible to feature them as authors, but we would like to take advantage of this section to thank them for their scientific contributions to this work.