To determine the prevalence of abnormalities in small airway function and sleep-disordered breathing in preschoolers born very preterm and with very low birth weight, and their association with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and other neonatal risk factors.

MethodsCross-sectional study of children aged 3 to 6 years born before 32 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of less than 1500 g. Respiratory oscillometry was performed, determining the resistance and reactance at 5 Hz (R5 and X5), the difference in resistance at 5 and 19 Hz (R5-19), area under the reactance curve (AX), and the resonant frequency (fres). Nocturnal oximetry was also performed, determining the oxygen desaturation indices at thresholds of 3% (ODI3) and 4% (ODI4). We analyzed the association of the results with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and other neonatal risk factors with the χ2 test or the Mann-Whitney U test.

ResultsThe sample included 22 children with a median (IQR) age of 4.9 (3.7–5.4) years, of who 54.5% had bronchopulmonary dysplasia. There was a high prevalence of abnormal results for all oscillometry parameters (R5-19, 10.0%; X5, 21.1%; R5, 25.0%; fres, 40.0%; AX, 45.0%) and oximetry parameters (ODI3, 38.1%; ODI4, 33.3%). None of these results were associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other neonatal risk factors.

ConclusionPreschoolers born very preterm and with very low birth weight have a high prevalence of abnormal small airway function and, probably, sleep-disordered breathing, unrelated to bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Determinar la prevalencia de anomalías de la función de las vías aéreas pequeñas y de trastornos respiratorios del sueño en preescolares nacidos con gran prematuridad y peso neonatal muy bajo, y su relación con la displasia broncopulmonar y otros factores de riesgo neonatales.

MétodosEstudio transversal, de niños de 3–6 años nacidos con peso < 1500 gramos y <32 semanas de edad gestacional. Se realizó oscilometría respiratoria, determinándose la resistencia y la reactancia a 5 Hz (R5 y X5), la diferencia de resistencias a 5 y 19 Hz (R5-19), el área de reactancia (AX) y la frecuencia de resonancia (Fres). Se realizó también oximetría nocturna, determinándose los índices de desaturación del 3% y 4% (ODI3, ODI4). Se estudió la asociación de los resultados con la displasia broncopulmonar y otros factores de riesgo neonatales mediante pruebas de chi cuadrado o Mann-Whitney.

ResultadosSe estudió a 22 niños de (mediana, rango intercuartil) 4,9 (3,7–5,4) años, el 54,5% con displasia broncopulmonar. La prevalencia de resultados anormales era alta en todos los parámetros de la oscilometría (R5-19: 10,0%, X5: 21,1%, R5: 25,0%, Fres: 40,0%, AX: 45,0%) y de la oximetría (ODI3: 38,1%, ODI4: 33,3%). Ningunos de esos resultados se relacionaban con la displasia broncopulmonar ni otros factores de riesgo neonatales.

ConclusiónLos preescolares nacidos con gran prematuridad y muy bajo peso neonatal tienen una prevalencia elevada de alteraciones de la función de las pequeñas vías aéreas y, probablemente, de trastornos respiratorios del sueño, no relacionados con la displasia broncopulmonar.

Advances in modern neonatology have achieved a reduction in mortality in infants born with very low birth weight (VLBW < 1500 g) and very preterm (VPT, gestational age < 32 weeks).1 This increased survival poses a challenge in terms of the future health of VLBW/VPT infants, including the long-term adverse effects of some neonatal intensive care interventions. The respiratory system is one of the organ systems that can be affected by the sequelae of prematurity.2

There is evidence of a persistence of an obstructive airway pattern in children with a history of VLBW/VPT, with decreased maximum expiratory flows, increased resistance in the small airways, air trapping, airway hyperresponsiveness, morphological changes in imaging studies (thickening of the airway wall), and, less frequently, defects in alveolar gas diffusion, all of this without evidence of an underlying inflammatory process.3–8 These abnormalities persist into adulthood and they seem worse in presence of chronic lung disease of prematurity/bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).9,10 Functional respiratory disorders manifest in the form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with recurrent respiratory symptoms, frequently triggered by viral infections, hospitalizations due to respiratory problems, limited physical capacity and need for bronchodilators and airway anti-inflammatories.11,12 Most severe episodes requiring hospital admission occur in children,13 but respiratory symptoms persist into adulthood.14

In general, clinical manifestations and functional impairment are greater the greater the prematurity, and a history of BPD could increase this risk.12,15,16 However, the extent to which BPD actually entails an increased risk of persistent lung disease, beyond the risk attributable to prematurity itself, other perinatal factors, and environmental exposures, is still under debate.4–6,17–21

Most previous studies have collected data from school age onwards, when it is easier to perform conventional lung function tests like spirometry. Respiratory oscillometry (OS) is a technique that requires less cooperation, is easier to perform and yields results in a shorter amount of time, which makes it suitable for assessment of lung function in preschoolers. Respiratory oscillometry measures the resistance and reactance of the respiratory system and is especially useful for identifying abnormalities in the distal airways, which can be important in chronic lung disease of prematurity/BPD.7 Several studies have found a correlation of OS and spirometry results in school-aged children with a history of prematurity.22 In preschoolers, several studies that applied OS found a very high prevalence of abnormalities, consisting in greater total airway and distal airway resistance values, without clear differences in relation to the history of BPD.3,23–25

Compared to lung function, there are little data on the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children born preterm. Some studies have found a high prevalence of SDB in school age and adolescence associated with prematurity.26 The risk seems to decrease with age until adolescence, after which it starts increasing again.27 However, the reported findings are not consistent.28 Studies in preschoolers are scarce and have found a high prevalence of SDB, possibly associated with BPD, and a decreasing tendency with increasing age.29

The objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence of abnormalities in respiratory mechanics and SDB in preschoolers with a history of VLBW/VPT and to analyze their association with neonatal characteristics such as gestational age, birth weight, treatment received in the neonatal unit or the diagnosis of BPD.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study in children born between 2018 and 2021 with a gestational age less than 32 weeks and a birth weight of less than 1500 g , who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital. We excluded children with no follow-up data in their electronic health records, residing outside the catchment area of the hospital, with diseases or malformations unrelated to prematurity that increase the risk of prolonged respiratory disease (bronchopulmonary malformations, congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiencies, polymalformative syndromes), and children with cerebral palsy or other type of neurologic damage that preclude correct performance of lung function tests. We defined BPD and its severity according to the criteria established by the Spanish Society of Neonatology and the Spanish Research Group on Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (GEIDIS)30: need of supplemental oxygen, positive airway support of high-flow nasal cannula for more than 28 days, and classify BPD severity according to the level of respiratory support required at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age (or at discharge, whichever comes first).

Nocturnal oximetry was performed using a digital pulse oximeter (Radical-7 with RD-SET sensor; Masimo Corporation, Irvine, California, USA), and the recordings were analyzed by means of the Visi-Download software (Stowood Scientific Instruments Ltd, Oxford, UK). The pulse oximeters were programmed without alarms, with an averaging time of 2 s, and records were made for a minimum duration of 6 h (recommendations of the Australasian Sleep Association31). We collected the following data for analysis: 3% oxygen desaturation index (ODI3: mean number of times the peripheral oxygen saturation [SpO2] dropped ≥3% from baseline per hour of recording), 4% oxygen desaturation index (ODI4: mean number of times the SpO2 dropped ≥4% from baseline per hour of recording), mean SpO2 during the recording and the percentage of time with SpO2 below 90% (CT90) and below 88% (CTT88).

In addition, the parents completed a brief version of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire, the Sleep-Related Breathing Disorder scale (SRBD-PSQ)32 translated and validated to Spanish.33 It is an instrument specifically designed to assess sleep-related breathing problems and appropriate for use in children from age 2 years, consisting of 22 items with three possible responses (“yes”, “no” and “don’t know”).

As recommended in the latest guideline of the British Thoracic Society,34 the following results were considered probably pathological: ODI3 > 7, ODI4 > 4 y SRBD-PSQ with positive answers in 33% or more of the items.

We assessed respiratory mechanics by means of OS with the tremoflo C-100 system (Thorasys Thoracic Medical Systems, Montreal, Canada), adhering to the standards of the European Respiratory Society.35 We collected data on the following parameters: resistance of the respiratory system at 5 Hz (R5), difference between the resistance at 5 and 19 Hz (R5−19), reactance a 5 Hz (X5), area under the reactance curve (AX) and resonant frequency (fres). We expressed the parameters as z scores relative to the reference values from the device-specific equations for the tremoflo C-100 developed by Ducharme et al.36 We considered increased values of R5, R5−19, AX or fres (z score > 1.645) and decreased values of X5 (z-score < −1.645) as abnormal.37

We administered a short questionnaire to parents asking about the family history of asthma, the child’s exposure to smoke and whether the child was being treated with inhaled corticosteroids for asthma.

We summarized all continuous variables as median and interquartile range. We analyzed the association between neonatal, sleep, respiratory mechanics and postnatal clinical variables using the χ2 test or the Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital (23-PI102). We obtained signed informed consent from parents prior to inclusion of patients in the study.

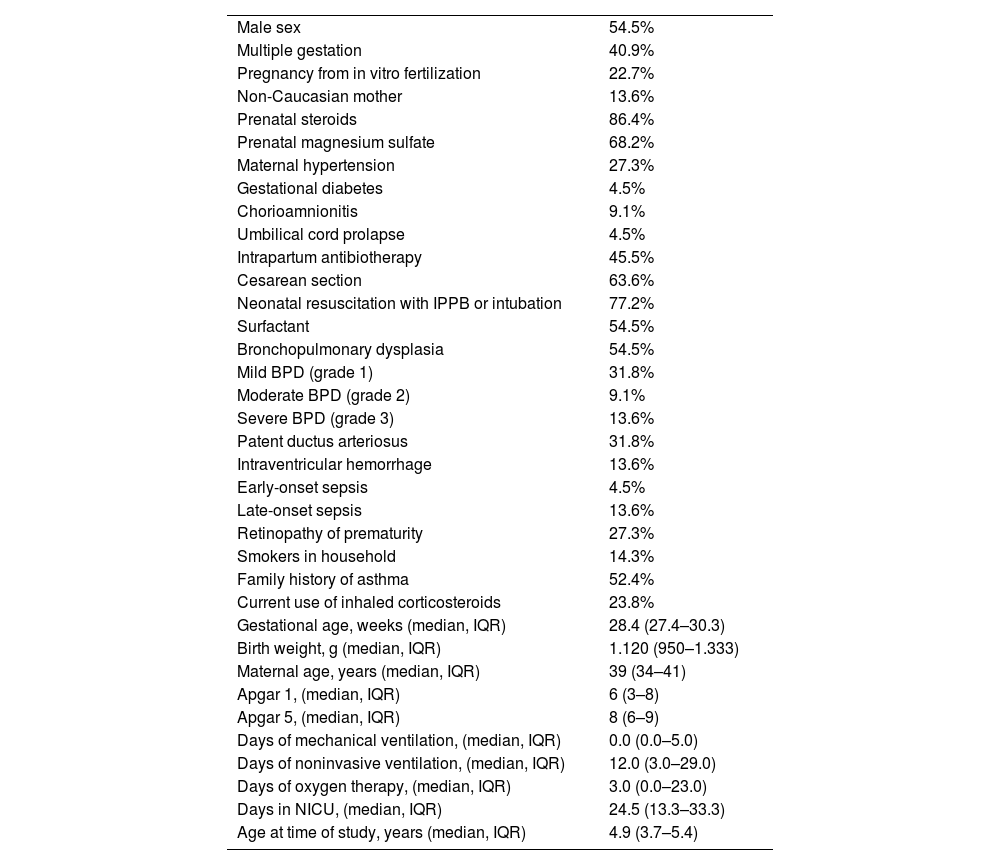

ResultsDuring the study period, 50 VLBW infants born before 32 weeks of gestation were managed at the hospital and survived to be discharged. We were unable contact 18 (36.0%) because they lived outside the hospital's catchment area. Another 10 (20.0%) declined to participate. In the end, 22 (44.0%) were included in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. There were no statistically significant differences between the patients who were included and those who were not in terms of sex, characteristics of pregnancy and childbirth, neonatal clinical course, need of ventilation or supplemental oxygen, days of stay in the intensive care unit or diagnosis of BPD. The mothers of included patients were older at the time of delivery: 39 (34–41) years vs 34 (25–36) years (P < .001). None of the patients in the sample were receiving oxygen or respiratory support at the time of the study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (n = 22).

| Male sex | 54.5% |

| Multiple gestation | 40.9% |

| Pregnancy from in vitro fertilization | 22.7% |

| Non-Caucasian mother | 13.6% |

| Prenatal steroids | 86.4% |

| Prenatal magnesium sulfate | 68.2% |

| Maternal hypertension | 27.3% |

| Gestational diabetes | 4.5% |

| Chorioamnionitis | 9.1% |

| Umbilical cord prolapse | 4.5% |

| Intrapartum antibiotherapy | 45.5% |

| Cesarean section | 63.6% |

| Neonatal resuscitation with IPPB or intubation | 77.2% |

| Surfactant | 54.5% |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 54.5% |

| Mild BPD (grade 1) | 31.8% |

| Moderate BPD (grade 2) | 9.1% |

| Severe BPD (grade 3) | 13.6% |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 31.8% |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 13.6% |

| Early-onset sepsis | 4.5% |

| Late-onset sepsis | 13.6% |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 27.3% |

| Smokers in household | 14.3% |

| Family history of asthma | 52.4% |

| Current use of inhaled corticosteroids | 23.8% |

| Gestational age, weeks (median, IQR) | 28.4 (27.4–30.3) |

| Birth weight, g (median, IQR) | 1.120 (950–1.333) |

| Maternal age, years (median, IQR) | 39 (34–41) |

| Apgar 1, (median, IQR) | 6 (3–8) |

| Apgar 5, (median, IQR) | 8 (6–9) |

| Days of mechanical ventilation, (median, IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–5.0) |

| Days of noninvasive ventilation, (median, IQR) | 12.0 (3.0–29.0) |

| Days of oxygen therapy, (median, IQR) | 3.0 (0.0–23.0) |

| Days in NICU, (median, IQR) | 24.5 (13.3–33.3) |

| Age at time of study, years (median, IQR) | 4.9 (3.7–5.4) |

Abbreviations: IPPB, intermittent positive pressure breathing; IQR, interquartile range; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

We were able to acquire acceptable OS recordings in 20 children, and 21 submitted valid nocturnal oximetry recordings.

Nocturnal oximetry resultsNocturnal oximetry recordings lasted a median (IQR) of 9:23 (9:00–9:50) h. We found a high ODI3 (>7) in 38.1%, a high ODI4 (>4) in 33.3% and an abnormal SRBD.PSQ in 33.3%. The median (IQR) ODI3, ODI4 and SRBD-PSQ values were 6.1 (4.4–9.3), 2.8 (1.7–4.4) and 15.0% (9.5%–38.9%), respectively. The oxygen saturation remained adequate during the recordings, with median (IQR) CT90 and CT88 values of 0.02% (0.00%–0.20%) and 0.00% (0.00%–0.04%). The average SpO2 was 95.1% (93.6%–95.9%).

Three children (14.3%) had abnormal results for both the PSQ-SRBD and the ODI3, and two (9.5%) had abnormal results for the PSQ-SRBD and the ODI4.

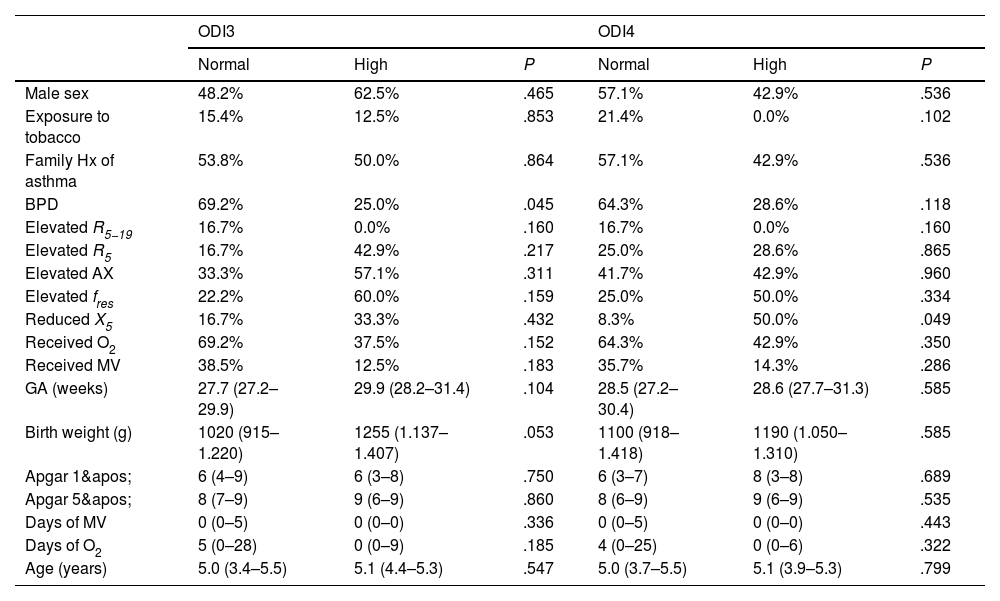

The prevalence of abnormal ODI3, ODI4 or PSQ-SRBD results was not higher in children with BPD nor children who required oxygen therapy or MV in the neonatal period, nor was it associated with gestational age, birth weight, age at the time of the study lung function abnormalities, with the exception of a marginally significant result between abnormal X5 and ODI4 values (Table 2).

Results of nocturnal oximetry.

| ODI3 | ODI4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | High | P | Normal | High | P | |

| Male sex | 48.2% | 62.5% | .465 | 57.1% | 42.9% | .536 |

| Exposure to tobacco | 15.4% | 12.5% | .853 | 21.4% | 0.0% | .102 |

| Family Hx of asthma | 53.8% | 50.0% | .864 | 57.1% | 42.9% | .536 |

| BPD | 69.2% | 25.0% | .045 | 64.3% | 28.6% | .118 |

| Elevated R5−19 | 16.7% | 0.0% | .160 | 16.7% | 0.0% | .160 |

| Elevated R5 | 16.7% | 42.9% | .217 | 25.0% | 28.6% | .865 |

| Elevated AX | 33.3% | 57.1% | .311 | 41.7% | 42.9% | .960 |

| Elevated fres | 22.2% | 60.0% | .159 | 25.0% | 50.0% | .334 |

| Reduced X5 | 16.7% | 33.3% | .432 | 8.3% | 50.0% | .049 |

| Received O2 | 69.2% | 37.5% | .152 | 64.3% | 42.9% | .350 |

| Received MV | 38.5% | 12.5% | .183 | 35.7% | 14.3% | .286 |

| GA (weeks) | 27.7 (27.2–29.9) | 29.9 (28.2–31.4) | .104 | 28.5 (27.2–30.4) | 28.6 (27.7–31.3) | .585 |

| Birth weight (g) | 1020 (915–1.220) | 1255 (1.137–1.407) | .053 | 1100 (918–1.418) | 1190 (1.050–1.310) | .585 |

| Apgar 1' | 6 (4–9) | 6 (3–8) | .750 | 6 (3–7) | 8 (3–8) | .689 |

| Apgar 5' | 8 (7–9) | 9 (6–9) | .860 | 8 (6–9) | 9 (6–9) | .535 |

| Days of MV | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–0) | .336 | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–0) | .443 |

| Days of O2 | 5 (0–28) | 0 (0–9) | .185 | 4 (0–25) | 0 (0–6) | .322 |

| Age (years) | 5.0 (3.4–5.5) | 5.1 (4.4–5.3) | .547 | 5.0 (3.7–5.5) | 5.1 (3.9–5.3) | .799 |

The percentages correspond to the occurrence of each variable in each category (normal/abnormal) of ODI3 and ODI4 values. The figures followed by parentheses correspond to median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: AX, area under reactance curve; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; GA, gestational age; fres, resonant frequency; MV, mechanical ventilation; ODI3, oxygen desaturation index 3%; ODI4, oxygen desaturation index 4%; O2, oxygen therapy; R5, respiratory system resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference between respiratory system resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; X5, respiratory system reactance at 5 Hz.

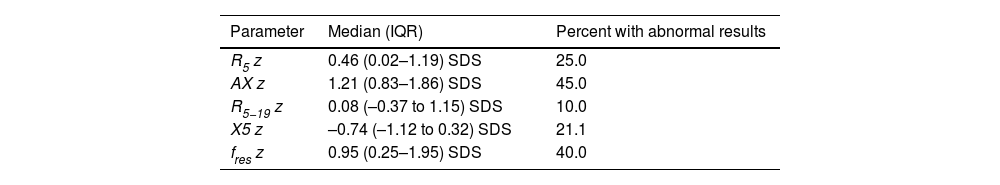

Table 3 presents the results. All OS parameters were frequently altered, especially the AX (Fig. 1). The prevalence of OS abnormalities was not greater in children with BPD (Fig. 2) nor those managed with oxygen therapy or MV in the neonatal period, nor was associated to gestational age or birth weight nor with the detection of abnormalities in the nocturnal oximetry. The OS results also did not change in relation to a family history of asthma, exposure to tobacco smoke or treatment with inhaled corticosteroids.

Results of respiratory oscillometry.

| Parameter | Median (IQR) | Percent with abnormal results |

|---|---|---|

| R5 z | 0.46 (0.02–1.19) SDS | 25.0 |

| AX z | 1.21 (0.83–1.86) SDS | 45.0 |

| R5−19 z | 0.08 (–0.37 to 1.15) SDS | 10.0 |

| X5 z | –0.74 (–1.12 to 0.32) SDS | 21.1 |

| fres z | 0.95 (0.25–1.95) SDS | 40.0 |

Abbreviations: AX, area under reactance curve; fres, resonant frequency; R5, respiratory system resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference between respiratory system resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; X5, respiratory system reactance at 5 Hz.

Percentage of patients with abnormal results in each of the respiratory oscillometry parameters. AX, area under reactance curve; fres, resonant frequency; R5, respiratory system resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference between respiratory system resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; X5, respiratory system reactance at 5 Hz.

Normalized values (z score) for the respiratory oscillometry parameters in children with and without a history of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The horizontal dashed lines mark the limits of normal (+1.645 y –1.645 SD). AX, area under reactance curve; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; fres, resonant frequency; R5, respiratory system resistance at 5 Hz; R5−19, difference between respiratory system resistance at 5 and 19 Hz; X5, respiratory system reactance at 5 Hz.

In this small sample of preschoolers with a history of VLBW preterm birth before 32 weeks of gestation, the prevalence of respiratory mechanics abnormalities was very high and indicative of predominantly distal airway involvement. Similarly, the prevalence of SDB was very high. Sleep-disordered breathing was not associated with either lung function or BPD or other possible perinatal risk factors.

The main limitation of the study was the small sample size, due to its being conducted in a single center. In addition, we assessed sleep disturbances using nocturnal oximetry as opposed to polysomnography. Although the ODI3 offers a high sensitivity and specificity for the identification of moderate to severe disturbances,38 we can only consider SDB in our patients probable, rather than confirmed. Furthermore, the concordance of results obtained by means of OS and conventional lung function tests is not perfect, there is still room for improvement in the standardization of OS, and its results are partly dependent on the system used and the applied reference values. On the other hand, we used a definition of BPD in line with current neonatal practice guidelines, but all definitions of BPD are inconsistent39 given that they do not have a sufficiently pathophysiological basis and address only one component (alveolar) of chronic lung disease.

Our results are consistent with those of other studies that have investigated lung function by means of oscillometry in preschoolers with a history of very preterm birth. Delestrain et al.23 found an elevated respiratory resistance (R5) that did not response to treatment with bronchodilators in 76% of children aged 4 years born extremely preterm (GA ≤ 28 weeks) and did not find any differences in association with BPD. Manti et al.,24 in a study in children aged 3 to 6 years born before 32 weeks of gestation, also found no differences in OS results or in the response to bronchodilators between children with and without a history of BPD. Lombardi et al.25 conducted a study in children aged 5 years born before 32 weeks of gestation and found elevation of R8 and AX in 16.5%, with no differences between children with and without BPD. Simpson et al.,3 in a study of children born at or before 32 weeks of gestation at ages 4 to 8 years, found a similar impairment in both oscillometry and spirometry in children with and without a history of BPD. Although the prevalence of disease may vary based on the oscillometry system and reference values used in the assessment, our study corroborated that preschoolers with a history of VLBW and VPT birth frequently had alterations in lung function, with a pattern of distal airway obstruction, that could not be attributed to the presence or absence of a past diagnosis of BPD.

In respect of SDB in preschoolers, several prospective studies have found an increased risk of SDB in children with a history of prematurity. Sadras et al.40 found a greater prevalence of SDB in children born between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation compared to those born to term in a sample of children under 2 years (mean age, 14.1 months). Contrary to our findings, they found a progressive reduction of the prevalence of SDB with increasing gestational age. In that study, the ODI3 in children born preterm was slightly higher compared to our study (median, 8.9 vs 6.1). Ortiz et al.29 studied children aged less than 3 years (mean age, 1.3 years) with BPD, nearly 60% required supplemental oxygen at the time of the study. The median ODI3 in that study was 5.5, and the prevalence of SDB was greater than 80%, mainly due to obstructive events. The frequency of SDB increased with the severity of BPD and rapidly decreased with increasing age. As occurred in our study, the prevalence of SDB was not associated with gestational age. We studied older children compared to these last two studies, using only nocturnal oximetry, and we did not find any association between nocturnal oximetry abnormalities and either BPD or gestational age, nor with the results of oscillometry.

In conclusion, in this sample of preschoolers born with VLBW before 32 weeks of gestation, there was a very high prevalence of both lung function abnormalities, with a pattern of small airway obstruction, and probably SDB, but these appeared to be independent phenomena unrelated to each other and to BPD.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Previous meeting: Partial results of this study were presented at the XLVI Reunión Anual Sociedad Española de Neumología Pediátrica (April 2025).