Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) affects adults predominantly, with the greatest number of admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU) and highest mortality found in this age group.1 Although coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children has been described as being less severe with a shorter recovery time,2 we present the case of a female patient aged 16 years, previously healthy and with no known contacts with COVID-19, that suffered severe pneumonia due to infection by SARS-CoV-2 requiring veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and experienced a full recovery.

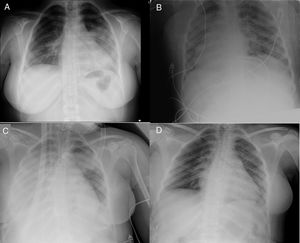

The patient presented to the emergency department of the regional hospital in her area with cough and fever of 6 days’ duration. The chest radiograph evinced pneumonia (Fig. 1A), which prompted admission to the inpatient ward. At 48 h, the PCR test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 turned out positive, so prescriptions were made for ritonavir/Lopinavir (for up to 7 days), hydroxychloroquine (for up to 10 days), azithromycin (for up to 5 days) and interferon β-1b (for up to 7 days). On the same day, the condition of the patient worsened, as she developed tachycardia, tachypnoea, dyspnoea, fever (39.9 °C) and her oxygen saturation (SaO2) dropped to 90% (4 L/min of supplemental oxygen). The patient was transferred to the ICU and immediately required orotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation (Fig. 1B). In the 72 h that followed, the patient was managed with neuromuscular blocking agents, a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 12–14 cmH2O, inhaled nitric oxide and ventilation in the prone position (2 sessions). After 4 days in the PICU, the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and the PaO2/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) worsened (the latter dropped to 70 mmHg for 6 h), which prompted activation of the mobile ECMO team of the tertiary care referral hospital in our autonomous community. The patient was connected to a portable ECMO system (Cardiohelp®, Maquet Cardiopulmonary AG, Hirrlingen, Germany) with a femoral-jugular veno-venous configuration (Fig. 1C): 21 F multistage drainage cannula and 19 F return cannula.

Plain chest radiograph. A) Chest radiograph in emergency department of the regional hospital B) Chest radiograph at admission in ICU of regional hospital (prone position). C) Chest department at admission to ICU after transfer to referral hospital (day 0 of ECMO). D) Chest radiograph in inpatient ward of referral hospital (discharge day).

After connection to the ECMO system, the patient was transferred to the ICU of the referral hospital. On arrival, she had a heart rate of 77 bpm and a blood pressure of 131/61 mmHg with administration of noradrenaline at a dose of 0.1 μg/kg/minute. She received ventilation with a tidal volume of 3 mL/kg of body weight, a FiO2 of 50% and a PEEP of 14 cmH2O. The initial ECMO blood flow was 4.2 L/min with a FiO2 of 100% (with a sweep of 4 L/min). The salient findings were lymphopaenia, marked elevation of interleukin 6, C-reactive protein, ferritin and d-dimer levels, and a negative troponin test (Table 1). At admission in the ICU of our referral hospital, we initiated treatment with tocilizumab (initial dose of 600 mg followed by 400 mg/12 h after), methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/24 h, 3 doses) and switched antiviral treatment to remdesivir (initial dose of 200 mg followed by 100 mg/24 h for 4 days).

Laboratory data. Ventilation and ECMO settings.

| Reference | ECMO day 0 | ECMO day 1 | ECMO day 2 | ECMO day 3 | ECMO day 4 | ECMO day 5 | ECMO day 6 | ECMO day 7 | ECMO day 8 | Post-ECMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12−14.5 | 9.2 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 9 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 9 | 9.2 |

| Leucocytes (×103/mm3) | 3.5−10.5 | 8.88 | 5.84 | 5.91 | 5.34 | 8.31 | 10.73 | 17.94 | 15.56 | 15.95 | 4.81 |

| Neutrophils (×103/mm3) | 1.8−8.0 | 7.11 | 4.06 | 5.90 | 3.46 | 5.5 | 7.23 | 14.21 | 11.47 | 12.50 | 11.78 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/mm3) | 1.5−7.0 | 0.77 | 1.12 | 1.51 | 1.20 | 1.45 | 2.18 | 2.09 | 1.52 | 2.00 | 2.18 |

| Platelets (×103/mm3) | 150−400 | 202 | 192 | 244 | 283 | 377 | 309 | 329 | 207 | 162 | 179 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9−4.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3 | 3.2 | 3.9 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 135−150 | 143 | 143 | 141 | 138 | 138 | 135 | 138 | 137 | 141 | 141 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5−5.5 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Ionised calcium (mg/dL) | 4.3−5.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 76−110 | 109 | 99 | 79 | 130 | 103 | 92 | 98 | 99 | 95 | 79 |

| ALT (U/L) | 5−35 | 23 | 25 | 32 | 38 | 61 | 53 | 51 | 45 | 44 | 41 |

| LDH (U/L) | 135−214 | 361 | 345 | 379 | 373 | 471 | 441 | 609 | 557 | 518 | 288 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 10−50 | 15 | 14 | 23 | 24 | 21 | 25 | 31 | 37 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.26−0.77 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| Arterial lactate (mmol/L) | 0.3−1.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| C-reactive Protein (mg/L) | 0−5 | 192.9 | 178.6 | 98.6 | 40.8 | 22.8 | 12 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 6 | 1.9 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) | 0−100 | 125.9 | 782.9 | 273.6 | 216.7 | 148.8 | 42.3 | ||||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 15−150 | 283 | 70 | ||||||||

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0−0.5 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 170−437 | 700 | 520 | 396 | 321 | 235 | 179 | 221 | |||

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 20−500 | 1275 | 1136 | 1751 | 3386a | 13 391a | 23 563a | 25 415a | 32 355a | 1374 | |

| Antithrombin III (%) | 80−130 | 87 | 106 | ||||||||

| pCO2 (mmol/L) | 55 | 41.8 | 46 | 46.5 | 46.8 | 44.7 | 46.7 | 47.8 | 42.8 | ||

| Ventilator FiO2 (%) | 100 | 60 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 40 | 35 | ||

| PaO2:FiO2 | 67 | 133 | 230 | 233 | 226 | 219 | 232 | 406 | 600 | ||

| PEEP (cmH2O) | 14 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Dynamic compliance (mL/cmH2O) | 15 | 24 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 25 | 34 | 41 | 45 | ||

| ECMO blood flow (L/min) | 4 | 4.2 | 4 | 4 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.5 | ||

| Sweep gas flow (L/min) | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| ECMO FiO2 (%) | 100 | 70 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 60 | 30 | ||

| Tidal volume (mL/kg) | 4.02 | 4.25 | 3.47 | 3.28 | 3.58 | 3.46 | 3.6 | 4.44 |

The patient responded favourably. The levels of proinflammatory cytokines went down and pulmonary function improved: increase in the PaO2:FiO2 ratio and improvement in dynamic compliance with a lower PEEP (Table 1). After 180 h, it became possible to discontinue ECMO and extubate the patient. After 8 days in the ICU and 7 in the inpatient ward of the referral hospital, the patient was discharged home without need of supplemental oxygen and was able to walk unassisted (negative PCR test for SARS-CoV-2) (Fig. 1D).

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation should be considered salvage therapy in cases refractory to conventional mechanical ventilation, ventilation in the prone position and/or recruitment manoeuvres.3 The frequency of ECMO utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic has been of 0.5%–1% of all hospitalised patients. In Europe, as of May 7, 2020, 1068 adult patients have required support with ECMO.4 Although cases of pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 have been reported in infants5, children6 and young adults,1 these patients have generally had good outcomes and rarely required extracorporeal life support. Our patient developed severe pneumonia refractory to standard therapy and required ECMO. The European Survey of Neonatal/Paediatric COVID-19 Patients in ECMO includes few patients, including ours.4 Adult patients with COVID-19 need between 20 and 50 days of ECMO to recover. In the case of our patient, 7 days of ECMO sufficed to maintain oxygenation and allowed delivery of ultra-protective ventilation until the inflammatory response abated. We did not detect any adverse effects of the combination of antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments used in the patient. We also did not need to adjust the usual dosage, so we surmise that there were no pharmacokinetic alterations associated with the use of the circuit or the extracorporeal membrane.

Many articles published during the current pandemic describe the course of disease in patients that remain in the ICU (even under ECMO). Ours is the first case of a paediatric patient managed with veno-venous ECMO that has fully recovered and been discharged home free of sequelae. In this case, extracorporeal life support proved safe (including an interhospital transfer), so it can be contemplated as an option in children and adolescents for management of COVID-19 if their condition requires such support.

Please cite this article as: Gimeno-Costa R, Barrios M, Heredia T, García C, Hevia Ld. Insuficiencia respiratoria COVID-19: soporte con ECMO para niños y adultos jóvenes. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:202–205.