Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis in children.1 It is characterised by symmetric ascending motor weakness and areflexia. GBS encompasses a group of acute immune-mediated acquired polyradiculoneuropathies that are usually preceded by gastrointestinal or respiratory infections. The most common forms are classified on the basis of neurophysiological criteria as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) and acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN).2 While both forms may be clinically indistinguishable, their prognosis can be very different. We present a case in which serial neurophysiological studies were key in the identification of a case of GBS with an atypical presentation, its classification as AMAN, and the assessment of the patient's outcome.

A male patient 7 years of age with no medical or surgical history of interest sought care in the emergency department for pain in the lumbar region and the right triceps surae accompanied by limited mobility in climbing and going down stairs lasting 11 days. We observed that the patient had difficulty walking on his toes, and the rest of the neurological examination was normal, including the deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). The findings of the lower limb X-rays were normal. He was discharged with a diagnosis of functional impairment due to nonspecific pain.

A week later he developed distal weakness in all four limbs that was evinced by muscle testing. The DTRs were brisk and symmetric. A previous history of acute gastroenteritis of two days of duration two weeks before the onset of symptoms was reported.

Myelitis was suspected due to the presence of hyperreflexia and tetraparesis, leading to initiation of a short course of oral corticosteroid therapy with a mild improvement of symptoms. Cranial and spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tests were requested. While the cranial MRI showed no abnormal findings, the spinal MRI revealed gadolinium uptake by the nerve roots of the cauda equina (Fig. 1), compatible with nonspecific radiculitis.

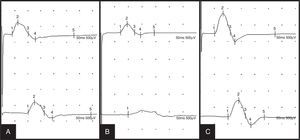

This was followed by an initial neurophysiological study of the four limbs consisting of sensory and motor neurography, F-wave latency measurement and electromyography. The sensory conduction findings were normal. All motor responses were low-amplitude (Fig. 2A) with preserved conduction velocity, associated with a significant reduction in F wave reproducibility. The findings were suggestive of a motor axonal polyradiculoneuropathy with no signs of muscle denervation.

Evolution of the findings of deep peroneal nerve motor neurography with distal stimulation at the ankle (tracings at the top) and proximal stimulation at the fibular head (tracings at the bottom): decrease in distal and proximal amplitude suggestive of axonal damage in the first study (A); motor conduction block 10 days later (B); amplitude measurements near the normal range 20 days later (C).

The analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid was normal. Serology was positive for Campylobacter jejuni. Tests for serum antiganglioside antibodies revealed the presence of IgG antiGD1a antibodies.

Ten days after the AMAN diagnosis and having observed clinical improvement, the neurophysiological study revealed a worsening of motor parameters, with evidence of nerve conduction blocks (Fig. 2B) and signs of incipient muscle denervation.

At 20 days, with the patient remaining asymptomatic, the repeat neurophysiological study showed improvement in motor conduction, which was almost normal (Fig. 2C), and mild signs of denervation with no loss of motor units.

While universal areflexia is typically a key feature in the clinical picture of GBS, there have been reports of atypical cases that present with normal or even overactive reflexes. Kuwabara et al.3 found a 33% incidence of hyperreflexia in patients with GBS, mostly in patients with AMAN and anti-GD1a antibodies. The physiopathological mechanism of this phenomenon could be explained by the presence of intact sensory nerves and a less severe motor axonal loss that would preserve the reflex arc,3,4 combined with involvement of spinal inhibitory interneurons resulting in distal conduction disturbances.4

While the MRI findings tend to be nonspecific, studies of GBS in children5 report contrast enhancement of the spinal roots in most of the cases.

Yuki6 associated AMAN with axonal degeneration and transient involvement of the nodes of Ranvier. While the AMAN subtype carries a poorer functional prognosis, the presence of conduction blocks is associated with a better recovery. In the case we present here, serial neurophysiological studies evinced the reversibility of motor nerve involvement, both for distal peripheral nerves (normalisation of neurography findings after initial evidence of conduction blocks) and proximal nerves (F wave restoration). The persistence of acute signs of muscle denervation in asymptomatic patients can be attributed to the axonal degeneration characteristic of the disease and the time gap that exists between clinical and electrophysiological manifestations.

The diagnosis of GBS in children may be delayed by the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms. Furthermore, the presence of hyperreflexia as an atypical manifestation may pose a challenge to the clinical diagnosis of GBS. In this context, neurophysiological studies acquire a greater relevance for the initial diagnosis, classification into the demyelinating subtype (AIDP) or axonal subtype (AMAN), and a better prognostic assessment of GBS.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez Guerrico I, Mínguez P, Aznar Laín G, Rubio MA, Royo I. Contribución de los estudios neurofisiológicos seriados en el síndrome de Guillain-Barré atípico. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:282–284.