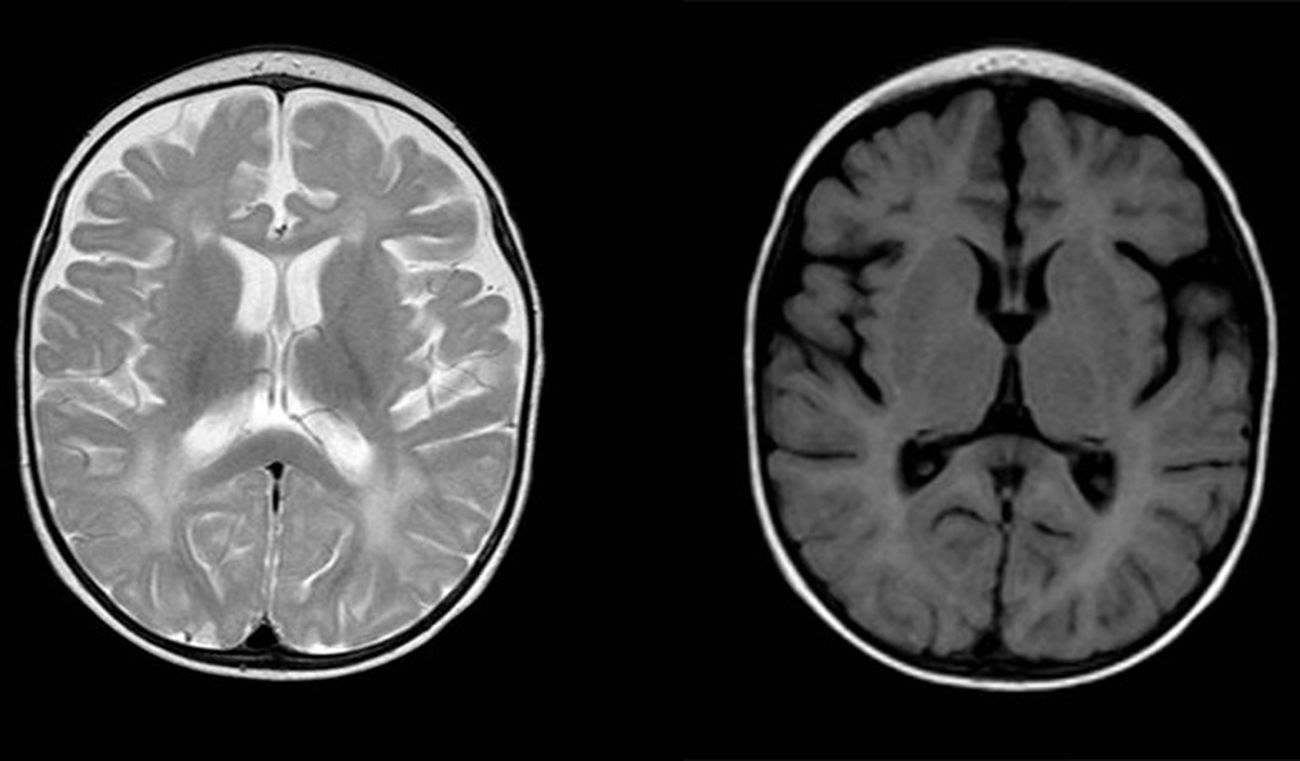

Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS) is a rare hereditary disease whose exact prevalence is unknown. It was first described in 1984 by Jean Aicardi and Francoise Goutières as a progressive encephalopathy with onset in the first months of life characterised by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lymphocytosis and calcifications in the basal ganglia.1 It manifests with irritability, psychomotor retardation, spasticity, dystonia, epileptic seizures, recurrent episodes of aseptic fever and microcephaly. The mortality is higher during the encephalopathic phase, and although the disease typically stabilises afterwards, it causes severe neurologic sequelae. Other characteristic features that may appear during its course are chilblains, ocular symptoms (mainly glaucoma), cardiac involvement or autoimmune disorders.2 Type I interferons play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of AGS, in which their expression is upregulated leading to increased production.3 For this reason, one of the classic laboratory findings in these patients is an elevated level of interferon alfa in CSF, along with pleocytosis and equally elevated levels of neopterin and biopterin. The potential usefulness of assessing the level of expression of interferon-stimulated genes by interferon in peripheral blood as a marker is currently being investigated, as there is evidence that these levels stay high past the encephalopathic phase (“interferon signature”).3–5 Another key feature is the detection of neuroimaging abnormalities including calcifications in the basal ganglia and changes in the white matter (Fig. 1). To date, we know of 7 genes whose mutations can lead to upregulation of the interferon pathway: ADAR, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, TREX1 and IFIH1. Heterozygous mutations have been described for the TREX1, ADAR and IFIH1 genes, whereas the mutations reported in all other genes have been homozygous.2 Mutations in the IFIH1 gene were detected most recently (2014)4 and are therefore the least frequent pathogenic variants, whereas mutations in the RNASEH2B and TREX1 genes account for the highest proportion of diagnosed cases of AGS.

Diffuse and patchy signal abnormalities in white matter in both cerebral hemisphere, hyperintense in T2-weighted images. Enlarged subarachnoid space with frontotemporal predominance in both hemispheres, with widening of the interhemispheric fissure and increased ventricular size (in the absence of increased pressure), compatible with cortical and subcortical atrophy.

In the past few decades, thanks to advances in genetics allowing the detection of these specific mutations, evidence has emerged of a broad phenotypic spectrum beyond the classic presentation based on the causative gene. We present the cases of 3 patients given a diagnosis of AGS in the past 8 years with the aim of analysing their clinical features in relation to the underlying genetic defect (Table 1). In general, the presenting features of AGS were consistent with those described in the most recent case series in the literature: neonatal presentation (33%), microcephaly (66%), psychomotor retardation (100%), spasticity (100%), severe intellectual disability (66%) and calcifications on cranial CT (66%), although only one patient had epileptic seizures.

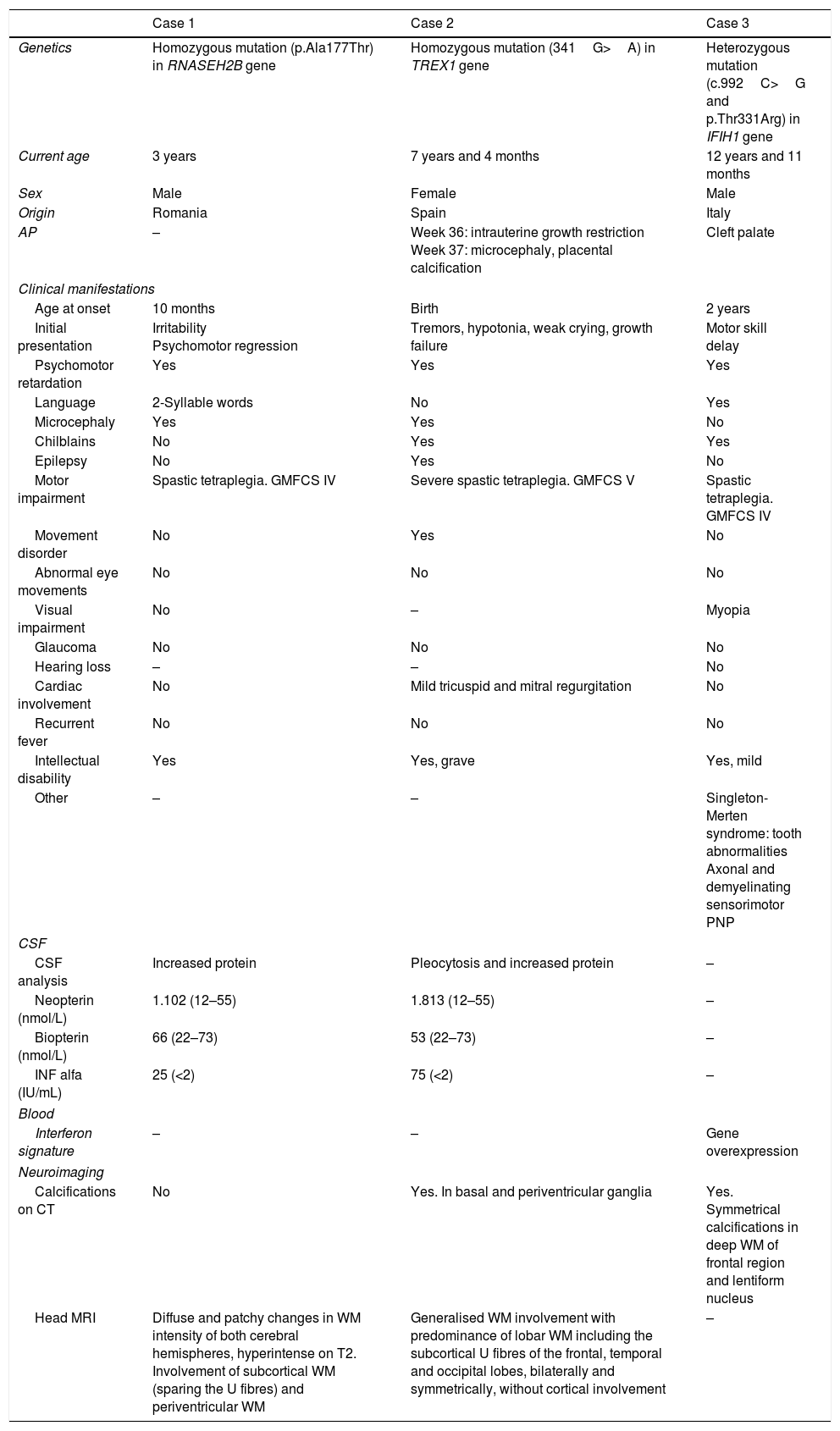

Characteristics of patients with Aicardi-Goutières syndrome.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetics | Homozygous mutation (p.Ala177Thr) in RNASEH2B gene | Homozygous mutation (341G>A) in TREX1 gene | Heterozygous mutation (c.992C>G and p.Thr331Arg) in IFIH1 gene |

| Current age | 3 years | 7 years and 4 months | 12 years and 11 months |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male |

| Origin | Romania | Spain | Italy |

| AP | – | Week 36: intrauterine growth restriction Week 37: microcephaly, placental calcification | Cleft palate |

| Clinical manifestations | |||

| Age at onset | 10 months | Birth | 2 years |

| Initial presentation | Irritability Psychomotor regression | Tremors, hypotonia, weak crying, growth failure | Motor skill delay |

| Psychomotor retardation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Language | 2-Syllable words | No | Yes |

| Microcephaly | Yes | Yes | No |

| Chilblains | No | Yes | Yes |

| Epilepsy | No | Yes | No |

| Motor impairment | Spastic tetraplegia. GMFCS IV | Severe spastic tetraplegia. GMFCS V | Spastic tetraplegia. GMFCS IV |

| Movement disorder | No | Yes | No |

| Abnormal eye movements | No | No | No |

| Visual impairment | No | – | Myopia |

| Glaucoma | No | No | No |

| Hearing loss | – | – | No |

| Cardiac involvement | No | Mild tricuspid and mitral regurgitation | No |

| Recurrent fever | No | No | No |

| Intellectual disability | Yes | Yes, grave | Yes, mild |

| Other | – | – | Singleton-Merten syndrome: tooth abnormalities Axonal and demyelinating sensorimotor PNP |

| CSF | |||

| CSF analysis | Increased protein | Pleocytosis and increased protein | – |

| Neopterin (nmol/L) | 1.102 (12–55) | 1.813 (12–55) | – |

| Biopterin (nmol/L) | 66 (22–73) | 53 (22–73) | – |

| INF alfa (IU/mL) | 25 (<2) | 75 (<2) | – |

| Blood | |||

| Interferon signature | – | – | Gene overexpression |

| Neuroimaging | |||

| Calcifications on CT | No | Yes. In basal and periventricular ganglia | Yes. Symmetrical calcifications in deep WM of frontal region and lentiform nucleus |

| Head MRI | Diffuse and patchy changes in WM intensity of both cerebral hemispheres, hyperintense on T2. Involvement of subcortical WM (sparing the U fibres) and periventricular WM | Generalised WM involvement with predominance of lobar WM including the subcortical U fibres of the frontal, temporal and occipital lobes, bilaterally and symmetrically, without cortical involvement | – |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; INF, interferon; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PNP, polyneuropathy; WM, white mater.

As noted before, homozygous mutations in the RNASEH2B gene are the most frequent variants that cause AGS and their phenotypic expression usually conforms the most to the classic presentation.4 This was the case of the patient in our study that carried such a mutation, who had onset at age 10 months with irritability and psychomotor retardation and with characteristic neuroimaging and CSF findings.

Twenty percent of cases of AGS may have a neonatal presentation, with the onset of disease occurring in utero.5 Mutations in any of the 7 aforementioned genes may lead to this phenotype, but this early presentation is most frequently associated with the TREX gene.4,5 The initial presentation of this form is similar to that of a TORCH infection, with hepatosplenomegaly, hypertransaminasaemia, thrombocytopenia and neurologic manifestations including extreme irritability, movement disorders and epileptic seizures.5 These patients have a more severe course of disease and are at higher risk of death. The patient in our sample that presented with such a variant had a neonatal presentation and currently has the most severe form of illness of the 3.

Mutations in the ADAR1 gene and especially the IFIH1 gene are associated with a late onset of symptoms, after 1 year of life with normal psychomotor development.5 In some of these cases, the syndrome has a benign course with relative preservation of language and motor skills. Our patient with a mutation in the IFIH1 gene was a singular case in that he also had Singleton-Merten syndrome, a rare disease also caused by a mutation in the IFIH1 gene and characterised by dental dysplasia, aortic calcifications and osteoporosis.6

Our aim is to underscore the significant phenotypic variability of AGS and its association with specific mutations for the purpose of both encouraging consideration of this diagnosis in cases with presentations that deviate from the classic form of disease and of contributing additional information on the course of disease and outcomes in these patients.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Medinilla EE, Villagrán García M, Mora Ramírez MD, Calvo Medina R, Martínez Antón JL. Síndrome de Aicardi-Goutières: espectro fenotípico y genético en una serie de 3 casos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90:312–314.