We present a case of protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) in the context of infection by Mycoplasma that we consider of interest because this disease is rare in childhood and no cases involving this aetiological agent have been previously reported in the literature.

The patient was a girl aged 3 years that presented to the emergency department with recurrent vomiting of 5 days’ duration, soft stools and asthenia in the past 3 days. She had a fever that peaked the day before admission (38°C) and an adequate urine output.

The patient had no perinatal history of interest. She had been formula-fed and introduced complementary foods without evidence of intolerance. The vaccinations were up to date (the patient had not received the vaccine against rotavirus). Her father had thalassaemia minor.

In the physical examination at admission, the patient weighed 14.3kg and had a body temperature of 36.8°C. Her general health condition was normal, with mild asthenia. Her nutritional and hydration status were both adequate. She had no exanthema or petechiae. The appearance of the oral cavity and pharynx was normal. Regular heart sounds with no murmurs. Lung sounds evinced good ventilation with a mild cough. The abdomen was soft and not tender, without masses or evidence of organ enlargement. The patient was conscious and alert, and exhibited no meningeal or focal neurologic signs.

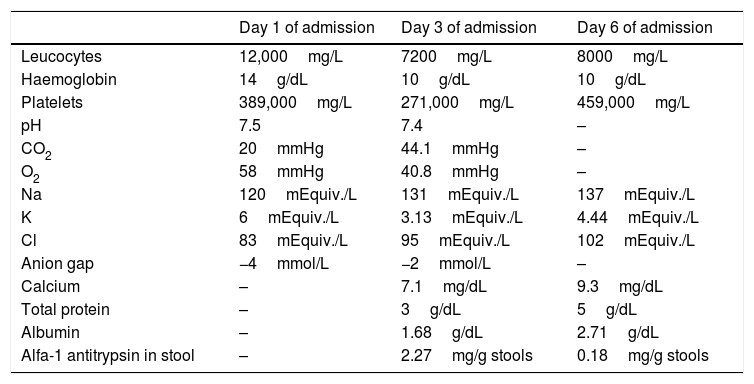

The blood tests performed at admission revealed a normal complete blood count and a mixed acid-base disorder with hyponatraemia and hypochloraemia (Table 1). The patient was admitted with a diagnosis of gastroenteritis to receive intravenous (IV) fluids.

Laboratory tests performed in our hospital to assess the patient during acute illness.

| Day 1 of admission | Day 3 of admission | Day 6 of admission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leucocytes | 12,000mg/L | 7200mg/L | 8000mg/L |

| Haemoglobin | 14g/dL | 10g/dL | 10g/dL |

| Platelets | 389,000mg/L | 271,000mg/L | 459,000mg/L |

| pH | 7.5 | 7.4 | – |

| CO2 | 20mmHg | 44.1mmHg | – |

| O2 | 58mmHg | 40.8mmHg | – |

| Na | 120mEquiv./L | 131mEquiv./L | 137mEquiv./L |

| K | 6mEquiv./L | 3.13mEquiv./L | 4.44mEquiv./L |

| Cl | 83mEquiv./L | 95mEquiv./L | 102mEquiv./L |

| Anion gap | −4mmol/L | −2mmol/L | – |

| Calcium | – | 7.1mg/dL | 9.3mg/dL |

| Total protein | – | 3g/dL | 5g/dL |

| Albumin | – | 1.68g/dL | 2.71g/dL |

| Alfa-1 antitrypsin in stool | – | 2.27mg/g stools | 0.18mg/g stools |

Treatment started with standard fluid therapy. Since the patient exhibited only modest improvement of hyponatraemia, oliguria, food refusal and asthenia, her hydration status was reassessed, with ordering of serial arterial blood tests and replacement of fluids. The hyponatraemia persisted despite resolution of vomiting and IV administration of adequate doses of sodium. On day 2 of admission, the patient developed symptoms of a common cold and abdominal distension, and on day 3 developed peripheral swelling, mainly in the eyelid area, a relentless cough and dysphonia, with increased abdominal distension. Additional laboratory tests were ordered that revealed hypoproteinaemia with hypoalbuminaemia, hyponatraemia and hypouricaemia with normal serum creatinine and chloride levels (Table 1). The results of Labstix strip urine test were negative.

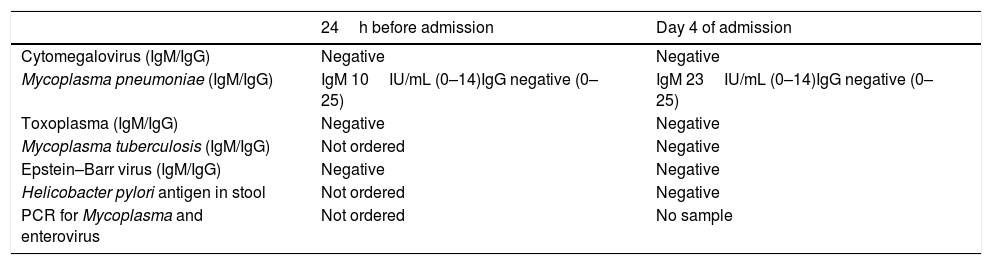

The patient underwent an abdominal ultrasound scan, whose sole abnormal finding was free fluid in the pelvis. Suspicion of PLE led to strict monitoring of fluid balance and measurement of alpha-1 antitrypsin in stool on 3 consecutive days, along with a request for an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Treatment with a dry high-protein diet was initiated, with IV administration of a proton pump inhibitor and fluids as needed based on the fluid balance. The evaluation was completed with serologic tests, which detected infection by Mycoplasma with a higher IgM antibody titre in the sample obtained 24h before admission compared to the follow-up test performed on day 4 of admission. Specific PCR could not be performed due to lack of a sample (Table 2).

Microbiological tests performed in the patient during acute illness.

| 24h before admission | Day 4 of admission | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus (IgM/IgG) | Negative | Negative |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae (IgM/IgG) | IgM 10IU/mL (0–14)IgG negative (0–25) | IgM 23IU/mL (0–14)IgG negative (0–25) |

| Toxoplasma (IgM/IgG) | Negative | Negative |

| Mycoplasma tuberculosis (IgM/IgG) | Not ordered | Negative |

| Epstein–Barr virus (IgM/IgG) | Negative | Negative |

| Helicobacter pylori antigen in stool | Not ordered | Negative |

| PCR for Mycoplasma and enterovirus | Not ordered | No sample |

The level of alpha-1 antitrypsin was elevated (2.27mg/g), which confirmed the suspected diagnosis of PLE, while the only possible aetiological agent identified was Mycoplasma, which led to initiation of azithromycin while awaiting the results of the endoscopy, which was scheduled for day 5 of admission.

On day 5, the patient exhibited significant clinical improvement, with resolution of the oedema and negative fluid balances and a gradual increase in the repeat measurements of serum protein levels. The scheduled endoscopy was cancelled due to this obvious improvement.

The Mycoplasma genus comprises the smallest self-replicating microorganisms ever described, which are responsible for several infections. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a recognised cause of atypical pneumonia that is endemic worldwide and affects children as well as adults. It has been associated with other diseases, such as pleuropericarditis, pleuritis, reactive arthritis, predominantly cutaneous vasculitis, cold urticaria, lymphocytic meningitis, disseminated encephalomyelitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, Adie syndrome and, infrequently and only in adults, PLE.1

The term PLE encompasses several infrequent diseases that share an excessive protein loss through the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in hyponatraemia possibly associated with oedema, ascites, pleural effusion and pericardial effusion.

The main diseases that cause PLE are parasitic infection, amyloidosis, ulcerative jejunoileitis, intestinal lymphoma intestinal, bacterial overgrowth, coeliac disease, Whipple disease, lymphangiectasia, amyloidosis, Crohn disease, Ménétrier disease, eosinophilic gastritis, erosive gastritis, stomach cancer, lymphoma, ulcerative colitis, and colon cancer.

It is characterised by hypertrophy of the gastric folds of the fundus and body, mucosal hypersecretion, protein loss and hypochlorhydria.1 Its pathophysiology has not been established, with different authors suggesting the possibility of infectious, autoimmune, endocrine and genetic aetiologies, and it is associated with an increased risk of stomach cancer (10%–15%).2,3

This disease is rare in childhood, usually manifesting before age 6 years with a sudden onset, persistent oedema and a benign outcome.1 In most of the published literature, cytomegalovirus (CMV) is considered the most probable aetiological agent, and Helicobacter pylori is another likely cause. Pathogens that are involved less frequently and have not been described in the literature include M. pneumoniae, Giardia intestinalis and herpes simplex.4

The initial presentation is nonspecific, similar to that of a viral illness, with appearance of peripheral oedema once hypoalbuminaemia has developed. Hypoproteinaemia and hypoalbuminaemia are typically present, and faecal alpha-1-antitrypsin is a sensitive and specific marker of protein loss in the gastrointestinal tract.4

There is no specific treatment for this disease. Spontaneous resolution usually occurs within 5 weeks from onset. The treatment plan is based on the causative pathogen. The management includes a diet rich in protein, antisecretory drugs, octreotide, anticholinergic drugs and possibly monoclonal antibodies.5

Surgical treatment is indicated in case of uncontrolled protein loss, bleeding, location near the cardia or dysplasia, as it eliminates the risk of malignant transformation. The right approach remains controversial, and the intervention should be adapted to the location and severity of the dysplasia.6

Please cite this article as: Carvajal Roca E, Fornes Vivas R, Tronchoni Belda M. Una complicación digestiva de la infección por Mycoplasma a tener en cuenta. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;91:199–200.