In our society, workplace violence is an alarming phenomenon: according to the latest report on aggressions to health care professionals in the national health system of Spain (2022), there were 20 reported attacks per 1000 professionals. Such violence is frequently considered “inevitable” and “part of the job”, and emergency care and psychiatric care settings are the ones where the rate of aggression is highest.1 Any hostile behaviour (HB) can cause, in addition to physical injuries, psychological harm, so it is important to study and prevent any type of attack, as recommended by various professional boards.1

To date, few studies have been conducted on the aggressions experienced by health care workers in paediatric emergency departments (PEDs). Consequently, we designed a study with the following objectives: (1) to describe HBs in the PED of a children’s hospital and (2) to determine whether there were significant differences compared to other care settings in the same hospital.

We conducted a single centre retrospective observational and descriptive study in a tertiary care children’s hospital serving medically complex patients. In our hospital, health care staff report experienced HBs on a voluntary basis through an electronic record system. The following variables are documented in these reports: care setting (emergency care, inpatient care, outpatient clinics, other), professional category, characteristics of the attack (mild verbal, verbal with gestures, mild physical and property damage), attacker, reason for attack, measures taken and impact on the health care worker.

The study included every recorded report (after anonymization) filed between September 2020 and September 2022. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the hospital (PIC-162-22). The results were analysed with the statistical software SPSS version 25 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). In the descriptive analysis, we summarised the data using the median and interquartile range (quantitative variables) or the frequency and percentage distribution (categorical variables). We used tests to analyse the distribution of the data, to compare qualitative data (χ2, contingency table, Fisher exact test). We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

During the study period, the health care staff of the hospital reported 205 attacks. Fifty-seven HBs (27.8%) took place in the PED, 95 (46.3%) in inpatient wards, 33 (16.3%) in outpatient clinics and 20 (9.6%) in other settings (gynaecology-obstetrics, street).

Of the 57 HBs reported in the PED, 38 were reported by nursing staff, 11 by doctors and 8 by administrative staff. The distribution by type of HB was 5 mild verbal attacks, 43 verbal attacks accompanied by gestures and 9 mild physical attacks; all the reported mild physical attacks took place in the context of restraining a patient. The aggressor was a relative/accompanying person in 44 cases and the patient in 13. The reasons that triggered the HB as reported by staff were waiting times (15), disagreement with the rules (12), agitation (12), disagreement with care plan (9) and worry (9). Fig. 1 presents the frequency distribution of the different types of reported HBs.

The measures taken were verbal de-escalation (57), physical restraining (10), contacting security personnel (12), contacting the point person (5) and contacting the police (4). Eighteen professionals reported having psychological sequelae and 8 physical sequelae. The psychological sequelae reported by the staff were discomfort (9), anxiety (9), worry (3), sadness (2) and fear (2).

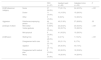

When we compared the HBs described at the PED with those described in other hospital settings (Table 1), we found statistically significant differences in terms of the professional category of the subject of attack, the aggressor, the type of HB and the trigger.

Differences in aggressive behaviours based on different hospital care settings.

| PED (n = 57) | Inpatient ward (n = 95) | Outpatient clinic (n = 53) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2,0]Professional category | Nurse | 37 (64.9%) | 77 (81.1%) | 24 (45.3%) | < .001 |

| Doctor | 11 (19.3%) | 10 (10.5%) | 15 (28.3%) | ||

| Other | 9 (15.8%) | 8 (8.4%) | 14 (26.4%) | ||

| Aggressor | Relative/accompanying person | 44 (77.2%) | 49 (51.6%) | 37 (69.8%) | .03 |

| [2,0]Type of attack | Mild verbal | 5 (8.8%) | 22 (23.2%) | 23 (43.4%) | < .001 |

| Verbal-gestures | 43 (75.4%) | 32 (33.7%) | 15 (28.3%) | ||

| Mild physical | 9 (15.8%) | 41 (43.2%) | 15 (28.3%) | ||

| [4,0]Reason | Waiting time | 15 (26.3%) | 2 (2.1%) | 7 (13.2%) | < .001 |

| Disagreement with rules | 12 (21.1%) | 20 (21.1%) | 9 (17%) | ||

| Agitation | 12 (21.1%) | 29 (30.5%) | 40 (7.5%) | ||

| Disagreement with medical plan | 9 (15.8%) | 25 (26.3%) | 19 (35.8%) | ||

| Worry | 9 (15.8%) | 19 (20.0%) | 14 (26.4%) |

PED, paediatric emergency department.

Thus, most HBs in the PED were verbal attacks with gestures on the part of relatives and/or accompanying adults and the most frequent reasons were the wait times and disagreement with the rules of the department. These results were consistent with other studies conducted in the adult emergency care setting, although in this setting it is usually the patient who attacks the staff.2 In addition, and also in agreement with the previous literature, most HBs targeted nursing staff, probably due to the closer and longer contact of nurses with patients.3

More aggressions were reported in inpatient care wards than in the PED, although the frequency of attacks in the PED may have been underreported due to the substantial workloads or a shorter contact with families. Furthermore, in inpatient care, physical attacks were more frequent and the proportion of HBs perpetrated by the patients was also greater.

Last of all, nearly one third of the staff that had experienced an attack reported having some form of psychological sequelae, although other authors have reported the presence of psychological disturbances in more than half of attacked professionals.4,5

In light of the above, further research is required to create awareness and monitor the issue of aggression against health care workers. In addition, agencies and institutions must develop strategies at the local and regional level to prevent this form of violence, manage these behaviours as they happen and follow-up with the staff to minimise their potential sequelae.

Webpage for data consultationInforme de Agresiones a profesionales del Sistema Nacional de Salud 2022 [accessed 25 April 2024]. Available at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/profesionesSanitarias/agresiones/docs/Informe_Agresiones.2022.pdf.

Previous meeting: This study was presented as an oral communication at the XXVII Annual Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, May 18–20, 2023, Las Palmas, Spain.