During pregnancy, physiological changes in the immune response make pregnant women more susceptible to serious infection, increasing the risk for the mother as well as the foetus, newborn and infant. All women should be correctly and fully vaccinated as they enter their reproductive years, especially against diseases such as tetanus, hepatitis B, measles, rubella and varicella. In addition to the recommended vaccines, in risk situations, inactivated vaccines could be administered to women who were not correctly vaccinated before, while attenuated vaccines are contraindicated.

Despite the fact that vaccination during pregnancy is a very important preventive measure and the existing recommendations from public health authorities, scientific societies and health professionals, the vaccination coverage could clearly be improved, especially against influenza and SARS-CoV-2, so any health professional involved in the care of pregnant women should proactively recommend these vaccines.

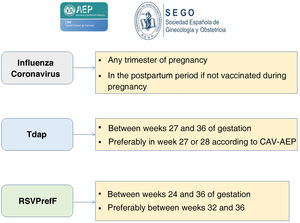

The Spanish Association of Pediatrics (AEP), through its Advisory Committee on Vaccines, and the Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (SEGO) recommend vaccination against the following diseases during pregnancy: against influenza and COVID-19, in any trimester of pregnancy and during the postpartum period (up to 6 months post birth) in women not vaccinated during pregnancy; against pertussis, with the Tdap vaccine, between weeks 27 and 36 of gestation (in the CAV-AEP recommendations, preferably between weeks 27 and 28); and against RSV, with RSVPreF, between weeks 24 and 36 of gestation, preferably between weeks 32 and 36.

Durante el embarazo, los cambios fisiológicos en la respuesta inmunitaria favorecen que las gestantes sean más susceptibles a infecciones graves, tanto para ellas como para el feto, recién nacido y lactante. Todas las mujeres deberían entrar en el período reproductivo con su calendario vacunal correctamente cumplimentado, sobre todo en lo que respecta a enfermedades como tétanos, hepatitis B, sarampión, rubeola y varicela. Además de las vacunas recomendadas, en situaciones de riesgo las vacunas inactivadas podrían ser administradas en aquellas mujeres que no estuvieran correctamente inmunizadas con anterioridad, mientras que las atenuadas están contraindicadas.

A pesar de que la vacunación durante el embarazo es una medida preventiva muy importante, y de las recomendaciones de autoridades sanitarias, sociedades científicas y profesionales sanitarios, las coberturas vacunales son claramente mejorables, especialmente en lo que respecta a gripe y COVID-19, por lo que todo profesional sanitario que atienda a la embarazada debe ser proactivo en aconsejarlas.

La Asociación Española de Pediatría, a través de su Comité Asesor de Vacunas, y la Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia recomiendan las siguientes vacunaciones durante la gestación: frente a gripe y COVID-19, en cualquier trimestre del embarazo, y durante el puerperio (hasta los 6 meses) en aquellas que no hubieran sido vacunadas durante la gestación; frente a tosferina con Tdpa, entre las 27 y 36 semanas de gestación (el CAV-AEP da preferencia entre las 27 y 28 semanas); y frente al VRS con RSVPreF, entre las 24 y 36 semanas de gestación, de preferencia entre las 32 y 36 semanas.

Vaccination of pregnant women offers two potential benefits. First of all, it protects pregnant women from infections to which they may be particularly susceptible due to the physiological changes in the immune response that take place during pregnancy, which in turn protects the foetus from congenital infections and other harmful effects of maternal infection. Secondly, it may be used to protect infants from infection in the first months of life, when they are most vulnerable, through the placental transfer of neutralizing immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and/or secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies in the mother’s breast milk.1

Importance of vaccination during pregnancyThe physiological adaptation that takes place during pregnancy, with a shift toward a predominance of humoral immunity (Th2 response), protects the foetus from immunologic rejection but makes pregnant women more susceptible to severe infections.2 Therefore, vaccination before conception and during pregnancy is a crucial measure to reduce morbidity and mortality in pregnant women, foetuses and infants.3

Influenza is particularly hazardous to pregnant women, with a mortality that is significantly greater compared to women who are not pregnant. In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the inclusion of pregnant women among the risk groups for the purposes of vaccination, which the World Health Organization (WHO) did in 2005 and the European Commission in 2009, following the H1N1 pandemic. In the 2021–2022 season,4 28 of the 29 countries in the European Economic Area recommended vaccination, 22 of them in any trimester and 6 in the second and third trimesters (in the case of risk factors, also in the first trimester). Bulgaria was the exception.

Pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are at increased risk of preeclampsia/eclampsia, severe infection, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), maternal mortality, preterm birth and a severe perinatal morbidity and mortality index.5

Due to the increased number of cases of pertussis in infants and deaths in infants aged less than 2 months, vaccination during pregnancy with tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) was introduced in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2012, which achieved a substantial impact. In Spain, Catalonia was the first autonomous community to implement this strategy in 2014; in 2015, it was approved by the Comisión de Salud Pública (Public Health Commission), and since 2016 it is implemented in every autonomous community in the country.

Since December 1, 2023, the first vaccine is available in Spain for administration to pregnant women to protect infants through age 6 months against respiratory syncytial virus, which causes significant morbidity (in Europe, one in 56 term infants are hospitalised due to this infection) and significant use of health care resources.6

Temporal trends in vaccination coverage during pregnancyAccording to the Vaccination Information System of the Spanish Ministry of Health (the SIVAMIN),7 which keeps records of administered vaccines, the overall vaccination coverage with influenza vaccine during pregnancy increased progressively between 2017 (29.60%) and 2020 (62.30%). In 2021 the trend changed, with coverage declining to 55.28%, decreasing further in 2022 to 53.59%, although this coverage is still somewhat greater compared to the coverage observed before the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these suboptimal coverages, Spain is the country in the European Union out of the four that provided data with the highest coverage from the 2018–2019 to the 2020–2021 season (the last for which data are available). 4 By autonomous community within Spain, in 2022 the coverage exceeded 75% in Andalusia (82.13%) and the Valencian Community (77.20%), while, on the other extreme, it was below 40% in Ceuta (17.87%), Catalonia (31.13%), Extremadura (32.96%) and Melilla (33.86%). There are no official data for the Balearic Islands.

As for the vaccination coverage with Tdap vaccine in pregnant women, there has been a progressive increase from 79.9% in 201 7 to 8 7% in 2021 and 2022.7,8 In 2022, all autonomous communities and Melilla had vaccination coverages greater than 80%, with the highest found in La Rioja (99.4%), Canary Islands (91.3%), Asturias (91.1%) and Castilla La Mancha (90.2%). There are no official data for Balearic Islands or Ceuta.

Lastly, when it comes to vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in the 2023–2024 season, as of January 15 only 2 European countries have published data: Ireland (18.3%) and Spain (6.5%).9

Vaccines given during pregnancyPertussisIn the past two decades, the incidence of pertussis has been increasing worldwide, independently of the vaccination schedules and coverages,10,11 making pertussis one of the most prevalent vaccine-preventable diseases. Some of the reasons are the waning of the immunity conferred by both the natural disease and vaccination, the switch from whole-cell to acellular vaccines (which, while causing fewer adverse reactions, offer shorter protection and do not prevent carriage), and the development of Bordetella pertussis strains, especially pertactin-deficient strains, that escape the immunity induced by the acellular vaccine.

The impact of this resurgence has been greatest on young infants, especially those who have yet to start the routine immunization schedule, who account for most of the mortality (chiefly infants aged less than 3 months) and can develop malignant pertussis with heart and respiratory failure, refractory pulmonary hypertension, cardiogenic shock and multiple organ failure.

In 2023, the number of cases of pertussis increased significantly in Spain (2211) compared to 2022 (241).12

Several strategies are available to prevent pertussis in infants, such as the cocooning strategy (which has not been found to be effective) or vaccination of adolescents, pregnant women, before conception or in the immediate postpartum period.13 Among them, vaccination of pregnant women is most effective, as it reduces the risk of hospitalization in infants aged less than 2 months as well as the length of stay. Programmes for vaccination of pregnant women were first implemented in 2012 in Argentina, the United States and the United Kingdom. At present, more than 40 countries, 28 of them in Europe, include vaccination against pertussis in pregnant women in their vaccination schedules in any of the recommended weeks of gestation, since starting from week 16 there is no difference in the concentration of antibodies passed to the infant against 2 of the 3 pertussis antigens.14 In Spain, the Advisory Committee on Vaccines (known as CAV, its acronym in Spanish) of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Paediatrics) recommends it since 2013, and the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System implemented this recommendation since 2015, a strategy that had a significant impact in preventing vaccination due to pertussis in infants aged less than 3 months. As regards vaccine effectiveness (VE), a recent study reported a VE of 89% in preventing hospitalization in infants aged less than 3 months and of 97% in preventing death,15 while another found a VE in preventing the disease of 70.4% at age 2 months and of 43.3% at age 7–8 months.16 Although there is evidence of a slightly decreased immunogenicity of the third dose of the vaccine primary series administered during childhood among infants whose mothers had been vaccinated during pregnancy, this did not translate to an increased risk of disease.15,16

The CAV-AEP and the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (SEGO, Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) recommend administration of the Tdap vaccine in each pregnancy between weeks 27 and 36 of gestation, as antibody levels wane over time. The CAV-AEP specifies it is preferable to administer it between weeks 27 and 28. If there is a risk of preterm birth, the Tdap can be administered from week 20.

Several studies have demonstrated the safety of this vaccination strategy for the mother, the pregnancy, the foetus and the newborn infant. A review that analysed 14 vaccine safety trials did not find differences between women vaccinated and not vaccinated during pregnancy or their offspring.17

InfluenzaPregnant women are at increased risk of disease and hospitalization due to influenza infection compared to women of reproductive age who are not pregnant.18 Some studies have found an association between infection in the first trimester and an increased probability of various congenital defects.19

Pregnancy is a risk factor that increases disease severity and mortality for both pandemic and seasonal influenza. Thus, during the 1918, 1957 and 2009 pandemics, mortality was four times greater in pregnant women compared to nonpregnant women. In the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, 5% of the mortality corresponded to pregnant women when pregnant women accounted for only 1% of the population.20 At the same time, it is estimated that during the influenza season, 4%–22% of pregnant women will develop respiratory tract disease and that their relative risk of hospitalization is nearly threefold that of nonpregnant women.21

Vaccination against influenza during pregnancy decreases the risk of infection and complications in pregnant women and their babies through age 6 months. One study found it reduced the risk of hospitalization in pregnant women by 40%.22 Another study found that maternal vaccination was associated with a reduction in hospital admissions and emergency department visits associated with influenza in infants aged less than 6 months. The VE was highest against hospitalization in infants younger than 3 months (53%) and infants born to mothers vaccinated in the third trimester (52%).23 This would justify, on one hand, postpartum vaccination of household contacts as well as of the mother in cases in which, for whatever reason, the mother was not vaccinated previously.

Vaccination of pregnant women has proven to be safe for both the mother and the foetus and newborn infant. A systematic review did not find an association between vaccination against influenza of pregnant women and an increased risk of foetal death, spontaneous miscarriage or congenital malformations.24 Another study found no evidence of an association with spontaneous miscarriage, chorioamnionitis, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm birth or congenital anomalies, admission to the neonatal unit, low Apgar scores or need of mechanical ventilation, while it found a protective effect against low birth weight and small for gestational age during periods of high influenza activity.25

In light of the above, we recommend vaccination of pregnant women with a dose of inactivated vaccine in any trimester of pregnancy during the influenza season and, if the mother had not been vaccinated, maternal vaccination of the mother within 6 months post birth.26,27

SARS-CoV-2Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 compared to nonpregnant women. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 92 studies comparing outcomes in pregnant patients with COVID-19 versus age- and sex-matched nonpregnant patients COVID-19 found that pregnancy increased the risk of need of intensive care (OR, 2.13), invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.59) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (OR, 2.02).28 During the delta wave, compared to previous SARS-CoV-2 variants, infection in unvaccinated pregnant patients was associated with an increased need of respiratory support (including ECMO) and maternal mortality. The severity of disease and the complications of pregnancy were similar in unvaccinated patients from the omicron wave until the start of the delta wave. Poor communication of the risks associated with infection by the omicron variant, which was perceived as less severe, can have a negative impact on the acceptability of vaccination for pregnant women.29 Maternal vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is the strategy that prevents severe disease during pregnancy while reducing the risk of adverse obstetric events, including gestational hypertension, caesarean delivery, preterm delivery or low birth weight for gestational age.

In short, vaccination offers a dual benefit: protection of pregnant women and protection of their offspring during infancy while they are not eligible for vaccination and depend on the immunity acquired from their mothers. In addition, maternal vaccination results in greater persistence of antibodies in infants compared to the immunity acquired after natural infection. Furthermore, the evidence supports the safety30,31 and effectiveness32–34 of vaccination during pregnancy and demonstrates that SARS-CoV-2 vaccines can be given at the same time as other vaccines routinely administered during pregnancy, such as the influenza or pertussis vaccines. For these reasons, we recommend vaccination with mRNA vaccines at any point during pregnancy, whether or not the pregnant patient has been previously vaccinated.35–37

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)Following the introduction in 2023 of nirsevimab, a monoclonal antibody, for the prevention of infection by RSV in newborns and infants aged less than 6 months as well as children with certain risk factor, the recent availability of a bivalent prefusion F protein subunit vaccine (RSVpreF) for vaccination of during pregnancy opens a new dimension in the preventive strategies against this pathogen. This vaccine is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use between weeks 32 and 36 of gestation and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for use between 24 and 36 weeks.

In April 2023, the results of a phase III trial (MATISSE) in pregnant women aged 18–49 years given a single intramuscular injection of 120 μg of RSVpreF or placebo between weeks 24 and 36 of gestation were published. The trial took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and excluded high-risk pregnancies (risk of preterm birth, multiple pregnancy, or a previous infant with a clinically significant congenital anomaly). The efficacy endpoints were medically attended lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI) and severe RSV-associated LRTI in infants within 90, 120, 150 and 180 days post birth. A lower boundary of the confidence interval (CI) for vaccine efficacy greater than 20% was considered to meet the success criterion for VE. The efficacy against severe LRTI was 81.8% (99.5% CI, 40.6–96.3) in the first 90 days post birth and 69.4% (97.58% CI, 44.3–84.1) at 6 months. The efficacy against medically attended LRTI was 57.1% (99.5% CI, 14.7–79.8, so it did not meet the criterion for VE) in the first 90 days post birth and 51.3% (97.58% CI, 29.4–66.8) through 180 days post birth. Maternal vaccination with RSVpreF did not prevent medically attended LRTI of any cause (not only RSV) within 90 days (efficacy, 7.0%) or 180 days (efficacy, 2.5%) post birth. No safety signals were detected in maternal participants or in infants and toddlers up to 24 months of age. The incidences of adverse events reported within 1 month after injection or within 1 month after birth were similar in the vaccine group (13.8% of women and 37.1% of infants) and the placebo group (13.1% and 34.5%, respectively).38

Both the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation in the United Kingdom39 and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC in the United States40 have established recommendations for maternal vaccination against RSV during pregnancy as one of the possible strategies to prevent severe infection by RSV in infants.

The AEP and the SEGO recommend, once RSVpreF is authorised for inclusion as part of the public health policy in Spain (it was not available in time for the 2023–2024 season), administration of a dose of vaccine to pregnant women between weeks 24 and 36 of gestation, preferably between weeks 32 and 36.

ConclusionThe physiological changes that take place during pregnancy make pregnant women more susceptible to infections, which may become severe or even fatal for the mother as well as the foetus, newborn or infant, in whom the immune response is still inefficient and, therefore, the maternal transfer of antibodies is essential for their protection in the early months of life.

All women should reach the reproductive age fully and correctly vaccinated, especially against diseases like tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, measles, rubella, mumps and chickenpox. During pregnancy, in addition to the recommended vaccines and in specific risk situations, inactivated vaccines could be administered to women who were not correctly vaccinated in the past, while attenuated vaccines are generally contraindicated.

Although vaccination during pregnancy is a very important preventive measure, and despite the issued recommendations and campaigns implemented by public health authorities, scientific societies and health care professionals, there is significant improvement to be made in vaccination coverages, especially when it comes to influenza and COVID-19.

Increasing the acceptability of vaccination and coverage rates in pregnant women depends on health care providers conveying adequate, reliable and evidence-based information about the corresponding diseases and the impact on the health of the mother as well as the foetus, newborn and infant. To do so, providers must receive specific training to help them provide this information and answer any question or concern that pregnant women may have regarding the safety and benefits of these vaccines. Any visit or checkup carried out by midwives, community nurses, obstetricians and family physicians is an opportunity that must be used to inform pregnant women and their close circle of the importance of protecting themselves and their future children from these diseases. Paediatric nurses and paediatricians, through their participation in maternal education or taking advantage of any visit made to the clinic by pregnant women with other children, should also engage in this objective. We must all be proactive in encouraging the administration of the vaccines recommended during pregnancy, given how important this public health strategy is.

The AEP, through its Advisory Committee on Vaccines, and the SEGO recommend administration of the following vaccines during pregnancy, as can be seen in Fig. 1:

- •

Vaccination against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 in any trimester of the pregnancy or during the postpartum period (up to 6 months post birth) in mothers who were not vaccinated during gestation.

- •

Vaccination against pertussis con Tdap between weeks 27 and 36 of gestation (preferably between 27 and 28 weeks according to the CAV-AEP). If there is risk of preterm birth, it can be administered from week 20 of gestation.

- •

Vaccination against RSV with RSVPreF between weeks 24 and 36 of gestation, preferably between weeks 32 and 36, as recommended by the EMA.

It is expected that other vaccines for pregnant women that are currently in clinical trials will be available in upcoming years, such as vaccines aimed at preventing cytomegalovirus or group B streptococcal infection in the foetus or newborn.

FundingThe development of these recommendations (analysis of the published data, debate, consensus and publication) has not been supported by any funding source outside of the logistic support provided by the AEP and the SEGO.

Conflicts of interest (last 5 years)JAA has collaborated in educational activities funded by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi and Seqirus, as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi and as a consultant in AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi advisory boards.

FJAG has collaborated in educational activities funded by Alter, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi and as a consultant in de GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi advisory boards.

MCFM has been a principal investigator and a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

TFF has participated in a Roche clinical trial as a researcher and has been invited to attend an educational activity sponsored by Pfizer and Roche.

AIA has collaborated in educational activities funded by AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, MSD and Pfizer and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer advisory boards. He has also received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, MSD and Pfizer to attend domestic educational activities.

MLR has participated in a GlaxoSmithKline clinical trial as the principal investigator.

IRC has collaborated in educational activities funded by GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi, as a researcher in vaccine clinical trials for Abbot, AstraZeneca, Enanta, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, HIPRA, Janssen, Medimmune, Merck, Moderna, MSD, Novavax, Pfizer, Reviral, Roche, Sanofi and Seqirus and as a consultant in GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi advisory boards.

ASF has collaborated in educational activities funded by Pfizer and as a researcher in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.