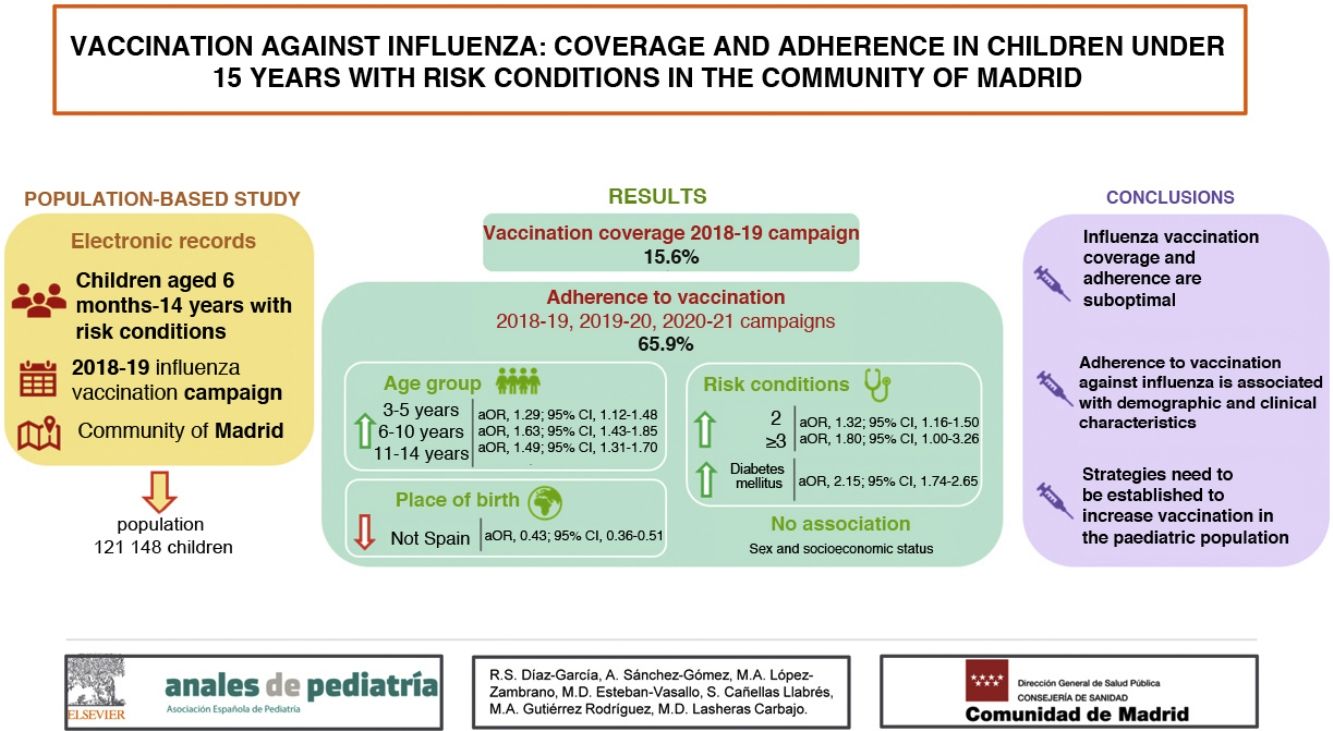

Vaccination against influenza is indicated in children at risk of complications or severe disease. The objective of this study was to describe the percentage of children aged less than 15 years with risk conditions vaccinated against influenza in the Community of Madrid, and to analyze the factors associated with adherence to vaccination throughout 3 vaccination campaigns.

Materials and methodsPopulation-based cross-sectional observational study of children aged 6 months to 14 years with conditions that indicated influenza vaccination at the beginning of the 2018−2019 campaign. Electronic population registers were used. We described the percentage of children vaccinated in 3 consecutive campaigns, and assessed the association of adherence to vaccination with demographic and socioeconomic variables and risk conditions using bivariate and multivariate analysis.

ResultsThe vaccination coverage was 15.6% in the 2018−2019 campaign. The adherence to vaccination was 65.9%. The variables associated with greater adherence were age greater than 2 years, especially in the 6−10 years group (aOR = 1.63; 95% CI, 1.43−1.85) and presenting more than one risk condition, especially 3 or more diseases (aOR = 1.80; 95% CI, 1.00−3.26). Diabetes mellitus was the disease associated most strongly with adherence (aOR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.74–2.65). Adherence was lower in the immigrant population (aOR = 0.43; 95% CI, 0.36−0.51). We found no association between vaccination adherence and sex or socioeconomic status.

ConclusionsVaccination coverage and adherence were suboptimal. Adherence to vaccination against influenza is associated with demographic and clinical conditions. Strategies need to be established to increase vaccination in children, with greater involvement of professionals and education of parents.

La vacunación antigripal está especialmente indicada en población infantil con riesgo de complicaciones o enfermedad grave. El objetivo de este estudio es describir el porcentaje de vacunación frente a la gripe en menores de 15 años con condiciones de riesgo en la Comunidad de Madrid, así como analizar los factores asociados a la adherencia vacunal a lo largo de tres campañas de vacunación.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional transversal de base poblacional de niños/as de 6 meses a 14 años y con condiciones de riesgo que fueran indicación de vacunación antigripal al inicio de la campaña 2018−2019. Se emplearon registros poblacionales electrónicos. Se describió el porcentaje de vacunados durante tres campañas consecutivas. Se analizó mediante análisis bivariado y multivariado la asociación de la adherencia vacunal con variables demográficas, socioeconómicas y condiciones de riesgo.

ResultadosLa cobertura vacunal fue del 15,6% en la campaña 2018−2019. La adherencia a la vacunación fue del 65,9%. Se asociaron a una mayor adherencia edad ≥3 años, fundamentalmente de 6−10 años (ORa = 1,63; IC 95% [1,43−1,85]) y presentar más de una condición de riesgo, especialmente ≥3 (ORa = 1,80; IC 95% [1,00–3,26]). Diabetes mellitus fue la enfermedad más asociada (ORa = 2,15; IC 95% [1,74−2,65]). Las personas extranjeras presentaron menor adherencia (ORa = 0,43; IC 95% [0,36−0,51]). No se encontraron diferencias en la adherencia según sexo ni nivel socioeconómico.

ConclusionesLa adherencia y cobertura vacunal se encuentran en niveles subóptimos. La adherencia a la vacunación antigripal se asocia a características demográficas y clínicas. Es necesario establecer estrategias para incrementar la vacunación en población infantil, con mayor implicación de profesionales y formación de progenitores.

Seasonal influenza is a disease that continues to have a substantial impact on global health1. The paediatric population is the age group most affected by this infection. In Spain, in the 2019−2020 season, the highest cumulative incidence of influenza occurred in children aged 0–4 years (n = 6244; 7 cases/100 000 inhabitants), followed by children aged 5–14 years (4995, 6 cases/100 000 inhabitants)2. In the early years of life, influenza results in a high hospitalization rate, which actually exceeded the rate observed in the elderly in the 2019−2020 season in Spain (52.4 cases/100 000 inhabitants in children <5 years versus 40.7 cases/100 000 inhabitants in adults ≥65 years)2.

The transmission rate is highest in the group aged less than 15 years2, making this subset of the population a key component in the chain of infection of influenza, both in the school and home setting, which entails substantial health care, social and economic costs, chiefly on account of school absenteeism and parental absenteeism from work3.

Vaccination is the main preventive measure against influenza. In Spain, until the 2021–2022 season, the indication for vaccination of the paediatric population approved by the Interregional Council of the National Health System focused exclusively in children aged more than 6 months with a high risk of complications of influenza infection due to the presence of personal risk factors (Appendix B in Supplementary material) or living with individuals at risk, on account of the risk of transmitting the infection to them4. In such cases, vaccination against influenza is funded by the public health care system.

It is estimated that approximately 16% of the paediatric population of the Community of Madrid in Spain has at least 1 chronic disease5. Two of the most prevalent diseases that are currently an indication for vaccination against influenza are asthma, which affects 10%–15% of the paediatric population in Spain6, and coeliac disease, affecting approximately 1%7. In the subset of patients under 15 years hospitalised due to influenza in Spain between 2014 and 2016, the most frequent underlying chronic condition was also asthma (15.4%), followed by immunosuppression (9.7%)8.

Starting in the 2020−2021 season, the Interregional Council of the National Health System established a target influenza vaccination coverage of at least 60%4. However, the vaccination coverage in in the paediatric population with risk factors is insufficient both in Spain9–11 and in the rest of Europe12. Knowing the factors that are associated both with vaccination and with the maintenance of adherence throughout several seasons is essential for the purpose of developing strategies to achieve the established target.

The factors associated to vaccination against influenza in the paediatric population have not been studied as thoroughly as in adults. Most of the studies have focused on vaccination coverage and associated factors9,13–15 or on groups with specific risk conditions16–18, especially asthma19. In Spain, thus far, adherence to influenza vaccination has only been studied in individuals with risk conditions and associated risk factors from age 65 years20.

The aim of our study was to describe the proportion of vaccination against influenza in children aged less than 15 years with risk conditions in the Community of Madrid and to analyse factors associated with adherence to influenza vaccination through 3 seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns (2018−2019, 2019−2020 and 2020−2021).

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a population-based cross-sectional observational study.

Study universeThe population under study comprised all children included in the public health care card holder database of the Community of Madrid in December 2018 who, on the date that the influenza vaccination campaign started in the 2018−2019 season, were aged at least 6 months and less than 15 years and had an identifiable risk condition constituting an indication for vaccination against influenza21.

Data sources and outcomesThe sources of information were the public health care database of the Community of Madrid including all individuals with an active public health card, the primary care (PC) health record database and the personal vaccination records in the public health information system (SISPAL) database of the Community of Madrid.

We collected data on sex and date and country of birth from the health card holder database. Since socioeconomic data were not available at the individual level, we used a deprivation index that is calculated for each census area based on a combination of indicators related to employment, education and internet access as a proxy measure22. We established the value for this index for each health district, categorising it into quintiles, and by extension attributed this value to individuals residing within that district.

We used the PC health record database to select the population of interest with any of the identifiable conditions that constituted an indication for vaccination against influenza in the 2018−2019 season by searching for the corresponding International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) codes: chronic cardiovascular diseases, asthma and other chronic pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, liver disease, haemoglobinopathies and anaemias, immunosuppression, coeliac disease, chronic inflammatory diseases and neurological or neuromuscular diseases or diseases manifesting with cognitive impairment (Appendix B in Supplementary material).

We obtained information regarding vaccination from the personal vaccination record database of the SISPAL. The latter database is integrated in the PC electronic health record (HER) system, with daily transfer of data for any new doses administered in PC centres in the public health system of Madrid to the SISPAL vaccination database. In addition, any other authorised vaccination site is obligated to record any administered doses directly to the SISPAL system through an online form.

AnalysisFor each child meeting the inclusion criteria, we collected data on the doses of influenza vaccine recorded in the SISPAL database through the unique patient identifier used in both the SISPAL and public health coverage card databases. We calculated the percentage of children vaccinated with at least 1 dose and fully vaccinated in each campaign, disaggregated by sociodemographic characteristics and risk condition. We categorised patients by age group based on their age at the start of the 2018−2019 vaccination campaign.

We defined full vaccination in vaccine-naïve children aged less than 9 years as administration of 2 doses of influenza vaccine at least 24 days apart. In children aged less than 9 years that had vaccinated at least once in previous vaccines and in children aged more than 9 years, we defined full vaccination as having received 1 dose of influenza vaccine during the seasonal campaign.

To assess adherence to influenza vaccination recommendations, we used children who received at least 1 dose of vaccine in the 2018−2019 campaign as the reference group. We defined adherence as having received the influenza vaccine again in the 2 subsequent campaigns.

To analyse the factors associated with adherence, we fitted logistic regression models, expressing the results crude odds ratios (ORs) for the bivariate analysis and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) in the multivariate analysis. The multivariate analysis included variables found to be significantly associated in the bivariate analysis. The OR and aOR values are presented with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We considered P-values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with the software IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical considerationsGiven the study design, it was not possible to seek informed consent from included individuals. All the data was obtained from population databases, were anonymised and were handled safeguarding confidentiality, in compliance with current laws on personal data protection and working protocols of the Directorate General of Public Health, and since the study was conducted by analysing population data for public health purposes, authorization by an ethics committee was not necessary.

ResultsIn December 2018, there were 1 021 788 children aged between 6 months and 14 years registered in the public health card database. Of this total, we excluded 26 536 who were removed from the system before the end of the study period (that is, before the end of the 2020−2021 influenza vaccination campaign), most frequently due to moving to a different autonomous community in Spain. Of the 995 252 remaining children, 12.2% (121 148) had a condition or underlying disease that could be identified in the PC health records that constituted an indication for vaccination against influenza, and therefore comprised the study universe. Table 1 presents their distribution based on their sociodemographic characteristics and risk conditions, out of which asthma was most prevalent (10.0%).

Characteristics of the population under study and of children vaccinated during the 2018–2019, 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 influenza vaccination campaigns in the Community of Madrid.

| PopulationN = 121 148n (%) | Vaccinated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018−2019 campaign | 2019−2020 campaign | 2020−2021 campaign | |||||

| At least 1 dosen (%) | Fully vaccinatedn (%) | At least 1 dosen (%) | Fully vaccinatedn (%) | At least 1 dosen (%) | Fully vaccinatedn (%) | ||

| Total | 18 861 (15.6) | 18 209 (15.0) | 18 723 (15.5) | 18 288 (15.1) | 26 231 (21.7) | 25 748 (21.3) | |

| Age group | |||||||

| 6 months-2 years | 4184 (3.4) | 1116 (26.7) | 1019 (24.4) | 1066 (25.5) | 988 (23.6) | 1316 (31.5) | 1264 (30.2) |

| 3−5 years | 16 226 (13.4) | 3364 (20.7) | 3116 (19.2) | 3254 (20.1) | 3073 (18.9) | 4344 (26.8) | 4090 (25.2) |

| 6−10 years | 51 263 (42.3) | 7468 (14.6) | 7161 (14.0) | 7499 (14.6) | 7323 (14.3) | 10 963 (21.4) | 10 786 (21.6) |

| 11−14 years | 49 473 (40.8) | 6913 (14.0) | 6913 (14.0) | 6904 (14.0) | 6904 (14.0) | 9608 (19.4) | 9608 (19.4) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 70 211 (58.0) | 11 181 (15.9) | 10 786 (15.4) | 11 002 (15.7) | 10 756 (15.3) | 15 477 (22.0) | 15 194 (21.6) |

| Female | 50 937 (42.0) | 7680 (15.1) | 7423 (14.6) | 7721 (15.2) | 7532 (14.8) | 10 754 (21.1) | 10 554 (20.7) |

| Country of birth | |||||||

| Spain | 116 905 (96.5) | 18 281 (15.6) | 17 683 (15.1) | 18 187 (15.6) | 17 774 (15.2) | 25 642 (21.9) | 25 168 (21.5) |

| Other | 4243 (3.5) | 580 (13.7) | 526 (14.4) | 536 (12.6) | 514 (12.1) | 589 (13.9) | 580 (13.7) |

| Socioeconomic status quintile | |||||||

| Q1 (highest SES) | 24 556 (20.3) | 3164 (12.9) | 3047 (12.4) | 3198 (13.0) | 3106 (12.6) | 5130 (20.9) | 4991 (20.3) |

| Q2 | 23 089 (19.1) | 3445 (14.9) | 3316 (14.4) | 3370 (14.6) | 3303 (14.3) | 5036 (21.8) | 4940 (21.4) |

| Q3 | 28 952 (23.9) | 4957 (17.1) | 4796 (16.6) | 4934 (17.0) | 4814 (16.6) | 6649 (23.0) | 6547 (22.6) |

| Q4 | 21 845 (18.0) | 3321 (15.2) | 3205 (14.7) | 3297 (15.1) | 3209 (14.7) | 4458 (20.4) | 4385 (20.1) |

| Q5 (lowest SES) | 22 704 (18.7) | 3974 (17.5) | 3845 (16.9) | 3924 (17.3) | 3856 (17.0) | 4958 (21.8) | 4885 (21.5) |

| Risk conditions | |||||||

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 4101 (3.4) | 626 (15.3) | 612 (14.9) | 688 (16.8) | 665 (16.2) | 948 (23.1) | 932 (22.7) |

| Asthma | 99 554 (82.2) | 15 552 (15.6) | 15 099 (15.2) | 15 299 (15.3) | 14 930 (15.0) | 21 510 (21.6) | 21 172 (21.3) |

| Other pulmonary disease | 2432 (2.0) | 343 (14.1) | 325 (13.4) | 335 (13.8) | 326 (13.4) | 474 (19.5) | 468 (19.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1557 (1.3) | 724 (46.5) | 710 (45.6) | 743 (47.7) | 733 (47.1) | 882 (56.6) | 878 (56.4) |

| Renal or hepatic disease | 976 (0.8) | 201 (20.6) | 188 (18.3) | 191 (19.6) | 186 (19.1) | 230 (23.6) | 227 (23.3) |

| Haemoglobinopathies and anaemias | 5916 (4.9) | 676 (11.4) | 630 (10.6) | 649 (11.0) | 619 (10.5) | 794 (13.4) | 778 (13.2) |

| Immunosuppression | 2764 (2.3) | 439 (15.9) | 417 (15.1) | 457 (16.5) | 446 (16.1) | 589 (21.3) | 573 (20.7) |

| Coeliac disease | 5007 (4.1) | 630 (12.6) | 565 (11.3) | 739 (14.8) | 693 (13.8) | 1280 (25.6) | 1204 (24.0) |

| Chronic inflammatory disease | 725 (0.6) | 219 (30.2) | 213 (29.4) | 229 (31.6) | 224 (30.9) | 269 (37.1) | 266 (36.7) |

| Neurologic or neuromuscular disease, disease with cognitive impairment | 3073 (2.5) | 787 (25.6) | 758 (24.7) | 818 (26.6) | 803 (26.1) | 972 (31.6) | 950 (30.9) |

| Number of risk conditions | |||||||

| 1 | 116 369 (96.1) | 17 593 (15.1) | 16 968 (14.6) | 17 442 (15.0) | 17 025 (14.6) | 24 600 (21.1) | 24 134 (20.7) |

| 2 | 4604 (3.9) | 1203 (26.1) | 1177 (25.6) | 1210 (26.3) | 1192 (25.9) | 1550 (33.7) | 1533 (33.3) |

| 3 | 169 (0.1) | 62 (36.7) | 61 (36.1) | 68 (40.2) | 68 (40.2) | 76 (45.0) | 76 (45.0) |

| 4 | 6 (0.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) |

SES, socioeconomic status.

In the population under study, the percentage of children that received at least 1 dose of influenza vaccine in the 2018−2019 campaign was 15.6%. In the 2019−2020 campaign, the percentage was 15.5%, and in the 2020−2021 campaign it rose to 21.7% (Table 1).

Table 1 shows the percentage of children fully vaccinated in each campaign. In the 2018−2019 campaign, there were 2027 vaccine-naïve children aged less than 9 years that were vaccinated, with documentation of full vaccination with 2 doses at least 24 days apart in 1375 of them (67.8%). Subsequently, the number of vaccine-naïve children aged less than 9 years who received the influenza vaccine was 1003 in the 2019−2020 campaign and 1522 in the 2020−2021 campaign, of who 568 (56.6%) and 1039 (68.3%), respectively, were fully vaccinated with 2 doses at least 24 days apart.

Table 1 presents the percentage of vaccinated children disaggregated by sociodemographic characteristics and risk condition. The risk condition with the highest percentage of vaccinated children was diabetes mellitus. We found that the percentage of vaccinated children tended to increase with the number of known risk factors.

Of the 18 861 children that received at least 1 dose of vaccine in the 2018−2019 campaign, 75.0% were vaccinated in the following campaign and 65.9% adhered to vaccination in the 2 following campaigns. In the 2019−2020 campaign, 18 723 children received at least 1 dose of vaccine, of who 15 430 (82.7%) were vaccinated in the 2020−2021 campaign.

Table 2 presents the results of the bivariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with adherence. Adherence was greater in children aged more than 2 years compared to younger children. Children born outside of Spain exhibited significantly lesser adherence (aOR, 0.43) compared to children born in Spain. The presence of more than 1 risk condition was associated with greater adherence, with the greatest increase found in children with 3 or more risk conditions (aOR, 1.80). We did not find differences in adherence based on sex or socioeconomic status.

Factors associated with adherence to vaccination throughout the 2018-2019, 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 influenza vaccination campaigns in the Community of Madrid.

| Adherencen (%) | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Age group | |||||

| 6 months-2 years | 636 (57.0) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| 3−5 years | 2118 (63.0) | 1.28 (1.12−1.47) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.12−1.48) | <0.001 |

| 6−10 years | 5098 (68.3) | 1.62 (1.43−1.84) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.43−1.85) | <0.001 |

| 11−14 years | 4584 (66.3) | 1.48 (1.31−1.69) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.31−1.70) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 7419 (66.4) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Female | 5017 (65.3) | 0.95 (0.90−1.02) | 0.143 | 0.96 (0.90−1.02) | 0.174 |

| Country of birth | |||||

| Spain | 12 167 (66.6) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Other | 269 (46.4) | 0.43 (0.37−0.51) | <0.001 | 0.43 (0.36−0.51) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status quintile | |||||

| Q1 (highest SES) | 2046 (64.7) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Q2 | 2251 (65.3) | 1.03 (0.93−1.14) | 0.565 | 1.02 (0.92−1.13) | 0.729 |

| Q3 | 3334 (67.3) | 1.12 (1.02−1.23) | 0.016 | 1.11 (1.01−1.22) | 0.027 |

| Q4 | 2163 (65.1) | 1.02 (0.92−1.13) | 0.694 | 1.01 (0.91−1.12) | 0.801 |

| Q5 (lowest SES) | 2642 (66.5) | 1.08 (0.98−1.20) | 0.108 | 1.08 (0.97−1.19) | 0.147 |

| Number of risk conditions | |||||

| 1 | 11 522 (65.5) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| 2 | 863 (71.7) | 1.34 (1.18−1.52) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.16−1.50) | <0.001 |

| 3 or more | 51 (78.5) | 1.92 (1.06−3.47) | 0.031 | 1.80 (1.00−3.26) | 0.051 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SES, socioeconomic status.

Multivariate analysis. Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = 0.015.

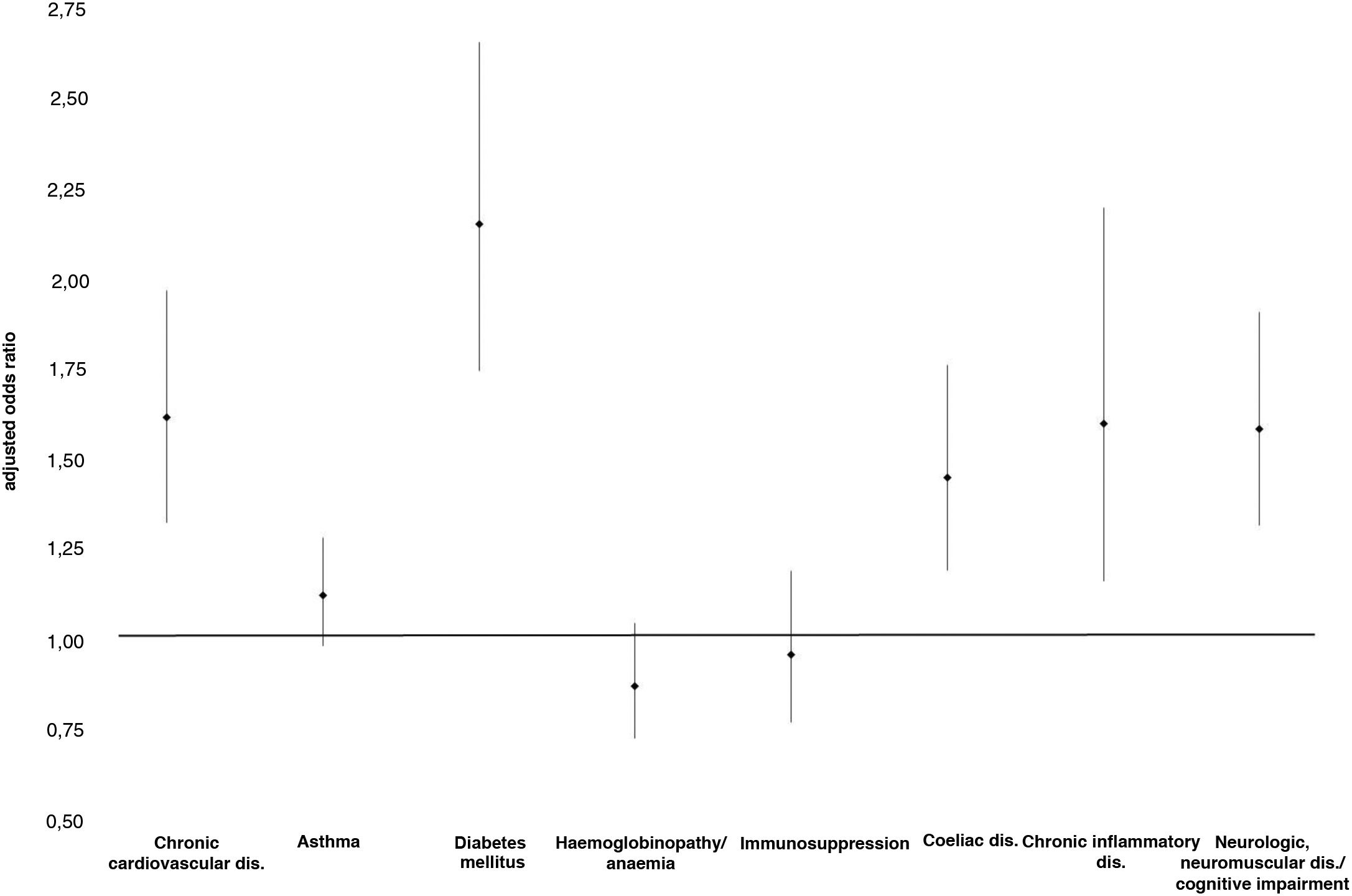

When we analysed each of the risk conditions in relation to other covariates by means of logistic regression, we found that diabetes mellitus was the risk condition associated with the highest adherence (aOR, 2.15), followed by chronic cardiovascular disease (aOR, 1.61) and chronic inflammatory disease (aOR, 1.60) (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThe influenza vaccination coverage in the paediatric population with risk conditions during the 2018−2019 campaign (15.6%) was similar to the coverage described previously in the Community of Madrid in the 2012–2013 campaign (15.7%)11, but lower compared to the coverage reported in the 2009–2010 campaign (27.1%), which coincided with the novel influenza A (H1N1) pandemic10. Higher vaccination coverages have been found in nationwide studies in Spain, both in the general population (17.5 %–19.1 %)13,14 and in children hospitalised due to influenza (25.9%)8, as well as in studies conducted in other autonomous communities, such as Catalonia (23.9%)9, but always far below the coverage target for individuals with risk conditions.

When we analysed vaccination in this cohort in the years that followed, we found a slight decrease in vaccination in the second campaign (15.1%) and a substantial increase in the 2020−2021 campaign (21.3%), which could be explained by the concurrent COVID-19 pandemic, during the importance of vaccination against influenza in at-risk individuals was emphasised.

The frequency of vaccination with 2 doses in vaccine-naïve children aged less than 9 years in our study ranged from 56.6% to 68.3%. This proportion is greater than the one reported in studies conducted in the United States23,24, although it is nonetheless insufficient and evinces the need to complete the recommended vaccination schedule in this age group.

Adherence to vaccination against influenza is a subject that has barely been explored, especially in children. Our study found that 65.9% of children aged less than 15 years with risk conditions vaccinated in the 2018−2019 adhered to vaccination in the next two campaigns. In Spain, there are currently only data on adherence in adults with risk factors over 2 vaccination campaigns (87%)20.

In our study, we found that adherence to vaccination against influenza in the paediatric population with risk factors increased with increasing age. This phenomenon has not been investigated in the past, but it could be due to older children tolerating the administration of an injectable vaccine better. Some studies have analysed the association of age with influenza vaccination coverage in children in risk groups with contradictory results9,13.

Our study did not find differences in adherence based on sex. A study conducted in Navarre did find an increased adherence with vaccination against influenza in men, but it focused on the population aged more than 65 years20. Other studies have found more frequent vaccination against influenza in male versus female subjects in both children10,11 and adults20,25.

In the subset of immigrant origin, we found a lower frequency of vaccination as well as lower adherence compared to Spanish nationals, which was consistent with the results of other studies on influenza vaccination coverage in both the paediatric and adult healthy or at-risk populations10,11,26, and on vaccination coverage in the paediatric population for the vaccines included in the routine immunization schedule27,28. Cultural factors could contribute to these differences.

In this study, we did not find an association between socioeconomic status and adherence to vaccination against influenza. We also did not find a clear linear trend in vaccination coverage in relation to socioeconomic status. The current evidence on the association of socioeconomic status and vaccination is contradictory. One study found that the frequency of vaccination against influenza in children with risk factors increased with increasing parental income13. Some studies have found an increased frequency of vaccination against influenza in association with lower educational attainment, either of the parents of children with risk factors19,26 or in the adult population17,18. Previous studies have found both an inverse association of socioeconomic status with vaccination coverage for vaccines included in the routine immunization schedule, attributed to an increased use of private health care services in higher-income households29, and a lack of differences based on social class or the type of health care insurance (public or private)30. In our study, the lack of differences could be due to the universal public health care coverage of children in Spain, which facilitates more consistent follow-up of children with risk factors in the public health care system.

The presence of more than one risk condition was associated with both a greater vaccination coverage and increased adherence to vaccination against influenza, which was consistent with previous evidence on adherence in adults13 and vaccination coverage in individuals in risk groups10,26,31.

In agreement with previous studies, we found that asthma was the most prevalent chronic disease in children8,10,11,16. The literature shows that influenza vaccination coverage is low11,16,19,32. In addition, our study did not find an association between the presence of asthma and an increased adherence to vaccination. The risk condition associated with the greatest frequency of vaccination was diabetes mellitus, with 46.5% of affected children vaccinated with at least 1 dose and 45.6% fully vaccinated, which was consistent with previous studies on vaccination coverage conducted in Madrid10,11, Catalonia9 and Valencia16. Diabetes mellitus was also the condition associated with the greatest adherence to vaccination, as was also the case in a study conducted in adults33. A possible explanation is that in the paediatric population, the most frequent form of diabetes mellitus is type 1, which requires frequent follow-up visits that offer numerous opportunities for health education and guidance, including in relation to vaccination against influenza. Previous studies have found that a higher frequency of health care visits is associated with an increased likelihood of vaccination against influenza34,35.

However, we found a lesser adherence in conditions associated with a high risk of complications of influenza infection, such as immunosuppression or neurologic diseases, which also require frequent contact with the health care system. The lower influenza vaccination coverage in these diseases has been described in previous studies9,31,36 and could be due to delays in vaccination due to concurrent disease or a higher frequency of hospital admission combined with concerns regarding the safety of influenza vaccines in these patients20,36,37. Another possible contributing factor is that the follow-up of these patients is chiefly conducted in specialty care as opposed to primary care, so that the onus of decision-making regarding the information, prescription and administration of vaccines would be shared by the two settings, possibly resulting in diffusion of responsibility as regards vaccination36–38.

This is the first study conducted in Spain that analyses influenza vaccination adherence in the paediatric population with risk conditions and changes in vaccination coverage in a cohort through several vaccination campaigns by reviewing individual vaccination records and electronic health records. The use of electronic records offers advantages compared to survey data, such as quicker data collection, yearly results, elimination of recall bias and the ability to identify diseases that are not included in surveys. In addition, it is reasonable to assume that few data were missing in vaccination records, as is the case in other studies with similar methodology11. One limitation of the study is that there are risk factors that are indications for vaccination against influenza in children that would not be found in the PC health records (eg, asplenia, haemophilia or use of immunosuppressive agents). Still, the prevalence of risk conditions was similar to the prevalence reported in other studies with a similar methodology10,11. Another is that since we could not obtain individual data on socioeconomic factors, we had to resort to the use of ecological data through the deprivation index. Also, the public health card register does not include individuals managed outside the public health care system, although we consider that the cohort was representative of the population, as it encompassed 95% of the total population of the Community of Madrid.

We found that adherence to vaccination against influenza and the corresponding vaccination coverage were suboptimal. Parents and especially paediatricians must be further educated on paediatric immunization against influenza, as vaccination against influenza in children is chiefly determined by the recommendation of the physician in charge13–15,18,20,39 and the available information and trust in the safety of the vaccine15,36. In addition, it is important to take advantage of the more frequent contact of children with risk conditions with health care staff to promote vaccination9,20.

In a study conducted in the United Kingdom in children aged 2–4 years in which adherence to vaccination with the nasal spray vaccine was greater than 80%, the development of adverse events following vaccination in children in this age group was the main reason given by parents to not continue vaccinating in successive campaigns40. We need to know the causes of nonadherence in our population and with the use of the vaccines administered in our region. It is important to continue investigating the reasons for the low adherence to vaccination against influenza, especially in children that start vaccination at a younger age, in the immigrant population and in individuals with specific risk conditions, and to implement strategies within immunization programmes to advance towards the established targets.

In conclusion, the influenza vaccination coverage in children is below recommended levels. Greater adherence to vaccination is associated with demographic (age at initiation of vaccination ≥ 3 years and Spanish versus foreign national origin), and clinical characteristics (> 1 personal risk factor). We found significant differences based on the specific risk factors, and diabetes mellitus was the disease most strongly associated with adherence.

FundingThis study did not receive any form of specific funding from the public, private or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.