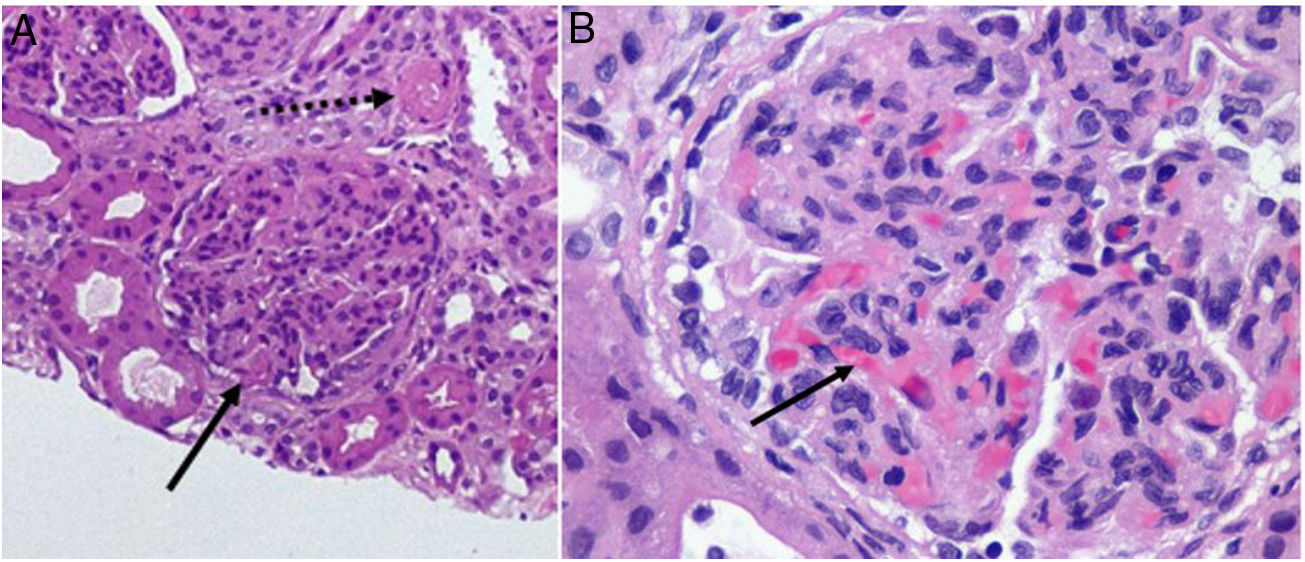

A Dominican girl aged 10 years sought care for fever without focus, vomiting and high blood pressure with onset 1 month prior. The blood tests results were: haemoglobin (Hb), 6 g/dL; schistocytes; positive direct Coombs test; platelets, 46 000/μL; creatinine (Cr), 2 mg/dL and nephrotic-range proteinuria (protein: creatinine ratio [Pr:Cr], 6 mg/mg); antinuclear antibodies (ANA,) 1/640; anti-dsDNA antibodies, 1/1280; C3, 23.1 mg/dL and C4, 2.8 mg/dL. The patient tested negative for Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and had normal ADAMTS13 activity. Given the suspicion of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) in the context of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), we initiated treatment with 3 intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone pulses (500 mg) followed by oral prednisone (1 mg/kg), IV cyclophosphamide (500 mg/15 days), IV eculizumab (900 mg/week) and sessions of haemofiltration to manage the progressive deterioration of renal function and uraemic encephalopathy. Examination of a renal biopsy specimen revealed features compatible with class IV lupus nephritis with active and chronic (A/C) lesions and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (Fig. 1). After 2 weeks, given the persistence of primarily haematologic activity, we added immunoglobulins (1 mg/kg) and rituximab (375 mg/m2/week for 4 weeks, alternating every other week with cyclophosphamide). After a month’s stay in hospital, the patient exhibited progressive and sustained improvement of renal function in absence of proteinuria (Cr, 0.82 mg/dL; Pr:Cr, 0.75 mg/mg) and of TMA (Hb, 11 g/dL; platelets, 378 000/μl). After completing the course of cyclophosphamide, the patient started maintenance treatment with mycophenolate (500 mg/12 h).

An Asian girl aged 8 years presented with poor general health. The salient findings of blood tests were: Hb, 8.4 g/dL; schistocytes; platelets, 11 000/μl, negative direct Coombs test; haematuria and Pr:Cr of 11 mg/mg with normal renal function; ANA, 1/640; negative anti-dsDNA test; C3, 60.9 mg/dL and C4, 12.8 mg/dL; ADAMTS13, 0% and negative anti-ADAMTS13 and genetic tests. The initial treatment consisted of IV methylprednisolone (3 boluses of 500 mg) followed by a step-down protocol of oral prednisone (1 mg/kg) and plasmapheresis. The patient exhibited a favourable haematological and renal response after 1 week of treatment, so she was discharged home. A month later, after withdrawal of steroid therapy, the patient presented with epistaxis and purpura in the lower extremities and blood tests results evincing worsening: Hb, 10 g/dL; platelets, 10 000/μl; Pr:Cr 5 mg/mg. The test for detection of anti-Ro52 antibodies was positive. Based on the suspicion of reactivation of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) in the context SLE, the patient once again underwent plasmapheresis and received treatment with methylprednisolone boluses and oral prednisone at a dose of 2 mg/kg. The patient exhibited a favourable haematologic response (Hb, 11 g/dL; platelets, 178 000/μl), and the subsequent examination of a renal biopsy specimen revealed features suggestive of class V lupus nephritis, prompting initiation of maintenance therapy with mycophenolate (1 g/12 h) that achieved normalization of the protein levels in urine and ADAMTS13 activity (95%).

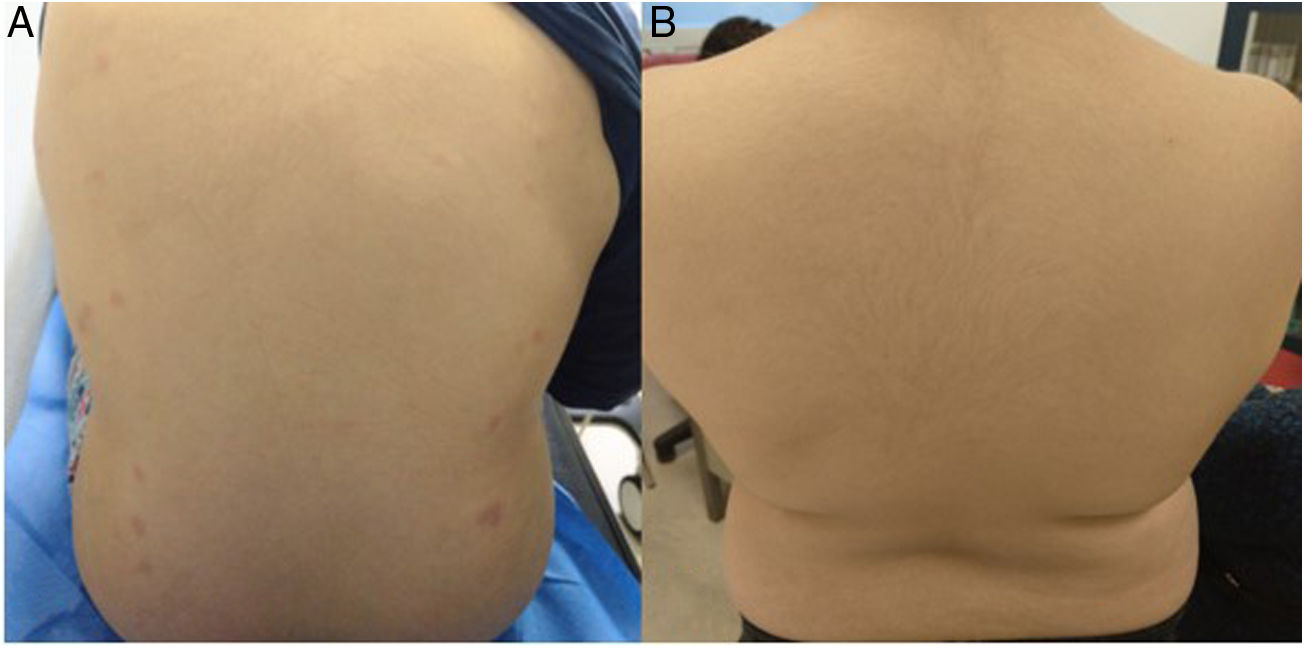

A Dominican boy aged 11 years presented with illness of 1 week’s duration characterised by fever, aphthae, a butterfly rash, erythematous oedematous plaques in the trunk (Fig. 2A) and polyarthralgia. The salient findings of blood tests were: white blood cell count of 2000 cells/μL; Hb, 10 g/dL; positive direct Coombs test; ANA antibodies, 1/1280; anti-dsDNA greater than 1/320; C3, 18 mg/dL and C4, 1.8 mg/dL; a triple positive antiphospholipid IgE antibody profile in absence of thrombotic features (strongly positive anticoagulant lupus test; anti-B2GPI IgG, 231.7 U/mL; ACA IgG, 70 U/mL); activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), 33 s; prothrombin percent activity (PT%), 52%; factor II, 33%; mixing study PT%, 85% indicative of factor II deficiency with no evidence of bleeding; mild haematuria; Pr:Cr, 1 mg/mg with normal renal function. The biopsy findings were compatible with acute cutaneous lupus, and the renal biopsy was postponed due to risk of haemorrhage, but it remained necessary because prognosis and treatment depend on the pathological classification of affected important organs. Treatment consisted of a step-down protocol of oral prednisone at an initial dose of 1 mg/kg and hydroxychloroquine at a dose of 200 mg/day, with clinical improvement of the skin and mucosae observed at 5 days (Fig. 2B) and normalization of coagulation (negative lupus antigoaculant test; anti-B2GPI IgG, 48 U/mL and ACA IgG, 26 U/mL; mixing study PT%, 77%; factor II, 60%) that was maintained throughout the follow-up. This allowed obtention of a renal biopsy sample the features of which were compatible with class III lupus nephritis. The patient started treatment with mycophenolate (500 mg/12 h) with normalization of urine sediment findings at 1 month. Three months later, rituximab was added (2 doses of 750 mg/m2 14 days apart) to manage refractory cutaneous and articular activity.

Thrombotic microangiopathies are characterised by haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia with variable organ involvement. The most frequent type is HUS secondary to infection by Shiga toxin-producing E. coli; atypical SHU results from a dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway of genetic aetiology that is treated with eculizumab, which blocks C5 and thus inhibits formation of the membrane attack complex1; TTP results from a congenital or acquired deficiency of ADAMTS13 activity. Secondary MATs develop in the context of various diseases, such as disorders of connective tissues (chiefly SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome). Systemic lupus erythematosus usually predates the onset of MAT (73%).1

The histological classification of lupus nephritis is an important prognostic factor. In addition to the classic subtypes, it is important to assess for the presence of other lesions, among which MAT is most relevant due to having the least favourable outcomes and being an independent risk factor for kidney injury.2 Forms associated with SLE used to be managed with immunosuppressive therapy and plasmapheresis,1,2 but since complement activation plays a role in both disorders, eculizumab has been used in recent series of patients with lupus nephritis refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy, achieving good responses.1 Other studies have reported clinical improvement and a lower cumulative steroid dose with the addition of rituximab to induction therapy, especially in black patients.3

The presence of TTP is associated with long duration of SLE, nephritis and high disease activity.4 Clinical manifestations and monitoring of enzymatic activity (which is normal in remission) can guide the diagnosis in case of negative antibody test results. Patients are managed with plasmapheresis until blood work findings improve or with immunoglobulin therapy combined with high-dose steroid therapy. The addition of rituximab may be helpful in refractory cases.4

Lupus anticoagulant hypoprothrombinaemia syndrome (LAHS) is associated with an acquired factor II deficiency and positive lupus anticoagulant results.5 It is most frequent in childhood5 and predominantly associated to connective tissue disorders.6 It is suspected in the presence of prolonged aPTT and PTT with full correction of PTT and minimal correction of the aPTT in the mixing studies.6 It manifests with bleeding (mainly of the skin and mucosae) but may be associated with thrombosis in patients with tissue disorders (10%).5 Treatment is based on plasma transfusions and steroid therapy alone or combined with an immunosuppressive agent depending on the systemic manifestations, which usually achieves normalization of coagulation and resolution of bleeding.5,6 At this point, the patients should be monitored for the potential development of thrombosis with initiation of platelet antiaggregation or anticoagulation therapy if necessary.5

Please cite this article as: Barrio Nogal L, Clemente Garulo D, de Lucas Collantes C, Aparicio López C, López Robledillo JC. Lupus eritematoso sistémico de debut atípico: a propósito de tres casos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:257–259.