Spinal cord compression (SCC) is an oncological emergency associated with significant morbidity, and early treatment is the most important factor in preventing neurologic sequelae.

The incidence in paediatric oncological patients is 3% to 5%. The tumour associated most frequently with SCC is neuroblastoma in children aged less than 5 years and sarcoma in older children.1

We conducted a retrospective study reviewing all cases of malignant SCCS over a 10-year period (2010–2020). We excluded patients aged more than 15 years due to hospital age range policy.

We identified a total of 14 cases, 9 in male patients and 5 in female patients (1.8:1). The median age was 4 years (interquartile range [IQR], 13−2).

The most frequently involved type of tumour was neuroblastoma (5/14), followed by Ewing sarcoma (3/14). The median age differed based on the type of tumour: 2 years in patients with neuroblastoma (IQR, 4.5−0.5) and 13 in patients with sarcoma (IQR, 15−4). Only one patient had a blood tumour (myeloid leukaemia).

In 8 patients, SCC was present at onset and in 6 it developed with disease progression. The median time elapsed to diagnosis was 6 days. In cases where it was present at onset, the delay was longer (15 days; IQR, 30−5]) compared to cases that developed with disease progression (2 days; IQR, 8.5−1).

The most frequent location was dorsal (9/14), followed by cervical (3/14), lumbar (1/14) and sacral (1/14).

In 13 patients, SCC was symptomatic at diagnosis. The most frequent symptoms were motor deficit (11/14), lumbar pain (7/14), bladder dysfunction (6/14) and anal sphincter dysfunction (3/14).

All patients received high-dose dexamethasone to protect the marrow. The targeted treatment consisted of surgical decompression (6/14), chemotherapy (5/14) and radiotherapy (3/14). We monitored the neurologic sequelae for a period of 2 years. Five patients had complete resolution of symptoms and 9 developed sequelae. Lower extremity paresis was the most frequent sequela (6/14), followed by bladder dysfunction (2/14) and anal sphincter dysfunction (1/14). Then patients survived the episode. In the group of patients who died, the median time elapsed to death was 4 months.

Spinal cord compression is a rare complication, but a high level of suspicion must be maintained to allow early initiation of treatment.

When it comes to specific treatment, it must be personalised based on the neurologic deficits, the body surface area to be irradiated, spinal stability, the chemoradiosensitivity of the tumour. In children with neuroblastoma or lymphoma, chemotherapy is the first-line treatment, while in cases of sarcoma, a multimodality approach with surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy is recommended.1

The most commonly used surgical decompression approach is laminectomy. This procedure allows collection of a biopsy sample and reducing the tumour. However, this approach is associated with a higher frequency of late sequelae.2

Radiotherapy is a treatment that has rapid effects. However, its use is progressively decreasing because it increases the risk of secondary tumours and its impact on neurologic outcomes is unknown. In our sample, all the patients treated with radiation were cases of progression. It was also used in 2 patients receiving palliative care, in whom radiotherapy achieved an improvement in quality of life.

As for chemotherapy, historically it has been assumed that the response to treatment was slower compared to radiotherapy and surgery.3 However, the findings of several studies contradict this conclusion, showing that chemotherapy is as effective as the other treatment options. In addition, chemotherapy causes fewer orthopaedic sequelae.4

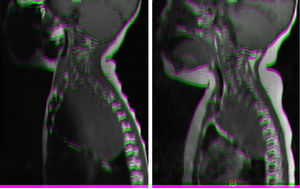

All patients managed with chemotherapy had favourable outcomes (Fig. 1) except one who required laminectomy. All were patients who presented with SCC at onset.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patient with neuroblastoma associated with spinal compression at onset. (a) Mass located in the right superior mediastinum measuring 7×5×9cm compressing the spinal cord from the C7-T1 level to the T3-T4 level. (b) MRI following administration of a carboplatin and etoposide cycle: mass measuring 5×5×8cm, with a smaller intracanal component and a reduced mass effect on the spinal cord, which has recovered in terms of both thickness and signal intensity.

Treatment should be initiated as soon as possible, with administration of dexamethasone in the first 48h. In the case of early neurologic deterioration, urgent surgical decompression is recommended. The risk of developing permanent sequelae ranges from 50% to 70%, and sequelae tend to be more severe the younger the age of the patient.5,6

Spinal cord compression is an oncological emergency that may cause significant morbidity, so early diagnosis is essential, especially in infants, given the nonspecificity of the symptoms, difficulty to assess pain and greater severity of sequelae in this age group.6

Strict criteria to determine which treatment is most suitable have yet to be established, although there is evidence that chemotherapy is at least as effective, achieving comparable if not improved outcomes, compared to other treatment modalities. Further research should be conducted in multiple centres and larger samples to establish firm conclusions regarding the selection of optimal treatment.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.