In young infants, infections by human parechovirus (HPeV) can cause illness ranging from mild respiratory or gastrointestinal disease to clinical sepsis, aseptic meningitis or encephalitis.1 Sepsis-like forms, especially in infants aged less than 3 months, continue to pose a diagnostic challenge due to the difficulty of distinguishing them from severe bacterial infection (SBI).2 The diagnosis of HPeV infections is based on the detection of viral genes by means of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in different biological samples (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], pharyngeal or nasopharyngeal exudate, serum or blood, stools or rectal discharge).3

At present, there are no established laboratory parameters that can help identify forms of HPeV infection associated with increased severity or length of stay. The aim of our study was to describe the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients admitted due to HPeV infection, analysing the factors associated with poorer outcomes.

We conducted a retrospective observational study in children aged less than 8 years admitted to the Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid, Spain) due to HPeV infection between January 2016 and December 2022 in whom blood tests were conducted at the time of admission. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

The diagnosis of HPeV infection was made based on positive PCR results in nasopharyngeal, rectal swab, blood and/or CSF samples. The samples were tested for enterovirus (EV) and HPeV with the commercial real-time PCR kit for enterovirus and parechovirus (RealCycler®, Progenie molecular®),4 and positive samples were submitted to the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (National Centre of Microbiology) for genotyping.

The statistical analysis was performed with the R statistics package (R-Studio Desktop, version 1.41106), and we considered differences statistically significance if the corresponding P value was less than 0.05. The mean length of stay in days was the dependent variable, and we used the Mann–Whitney U test to compare its values in pairs of independent groups formed based on the established cut-off point for each clinical parameter and the findings of the triage performed on arrival to the emergency department using the paediatric assessment triangle, the Young Infant Observation Scale (YIOS) and the Rochester criteria for low risk of bacterial infection.

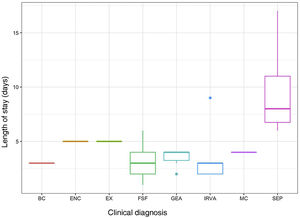

The sample included a total of 35 patients with a median age of 2 months (interquartile range [IQR], 0–8), with a predominance of male patients (21/35; 60%). The most frequent diagnosis was fever without source (FWS), followed by respiratory infection, gastroenteritis and sepsis-like illness. The median length of stay was 3 days (IQR, 2–5).

The length of stay was significantly longer in patients who had mild elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP≥20mg/L) and procalcitonin (PCT≥0.12ng/mL) at the time of admission, in absence of thrombocytosis and leucocytosis (although with mild neutrophilia), and with slightly elevated haemoglobin values. Table 1 summarises the results of the statistical analysis.

Comparison of obtained laboratory values to established cut-off points.

| Laboratory parameter | Cut-off point | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leucocytes (cells/mm3) | <14 500 | ≥14 500 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 4.38 | 1.2 | 0.02* |

| Neutrophils (cells/mm3) | <6000 | ≥6000 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 3.52 | 5.54 | 0.04* |

| Lymphocytes (cells/mm3) | <3100 | ≥3100 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 4.66 | 3.38 | 0.07 |

| Platelets (count/mm3) | <350 000 | ≥350 000 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 4.6 | 3.27 | 0.04* |

| Haemoglobin (g/mm3) | <13.5 | ≥13.5 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 3.59 | 6.42 | 0.02* |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | <20 | ≥20 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 3.58 | 5.77 | 0.02* |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | <0.12 | ≥0.12 | |

| Length of stay, days (mean) | 2.62 | 4.3 | 0.01* |

Values presented in bold face: increased mean length of stay associated with blood test results.

In the sample under study, 17.1% of the patients (6/35) required admission to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), of whom 2 received a diagnosis of sepsis, and had a significantly greater elevation of the white blood cell and neutrophil counts (increased leucocytosis and neutrophilia).

The evaluation of infants aged less than 3 months with FWS (n=8) included a complete blood panel with chemistry whether or not they met the criteria for high risk. In this group of patients, 37.5% (3/8) had normal results in the triage and had longer lengths of stay, although the difference was not significant. Two of these three patients with normal results at triage had values of CRP greater than 20mg/L at admission. Patients with sepsis-like illness had significantly longer stays compared to patients with other diagnoses. Fig. 1 presents the distribution of the length of stay based on the clinical presentation.

The current evidence on HPeV infection in the paediatric population is still scarce, and mostly focuses on the clinical characteristics of the patients.

Our study contributes additional information by identifying laboratory parameters and diagnoses or clinical presentations associated with an increased length of stay and less favourable outcomes.

In addition to the complete blood count parameters discussed above, we ought to highlight the CRP and PCT values, as these are relevant parameters for the identification of SBI. In our case series, CRP levels of 20mg/L or greater and PCT levels of 0.12ng/mL or greater at the time of admission were associated with longer stays, although the levels were far from those found in patients with SBI.

In our hospital, the protocol for the evaluation of febrile infants aged less than 3 months includes the collection of samples (rectal, pharyngeal and/or blood) for testing for HPeV and EV.5 A positive result in these tests, especially for rapid tests, associated with laboratory data indicative of a favourable outcome, as described in our study, could achieve a reduction in the number of diagnostic tests performed, the use of unnecessary antibiotherapy or the length of stay or even allow avoiding hospital admission altogether. The clinical presentation at the time of admission does not seem to be the sole determinant for the performance of blood tests, and a significant percentage of children with normal findings at triage had laboratory values at admission that were associated with the length of stay. In addition, the presence of leucocytosis with neutrophilia at the time of admission should be considered a red flag warning of a potentially severe course, as patients who required admission to the PICU had significantly higher values. The diagnosis of sepsis-like illness was also associated with an increased length of stay, an outcome that was expected and has been previously described in the literature.6

In conclusion, complete blood count and blood chemistry results at the time of hospital admission should be used to alert the care team of a potentially severe course and be taken into account in the management of the patient.

FundingThis study was partially funded under two Health Care Facility Strategic Action (AESI: Acción Estratégica de Salud Intramural) projects that included the study of the analysed samples (PI15CIII/00020 and PI18CIII/00017). Spain.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Iker Falces-Romero. Department of Microbiology, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Fundación IdiPaz, CIBERINFEC ISCIII, Madrid, Spain.

Almudena Gutiérrez Arroyo. Department of Microbiology, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

Ana Méndez Echeverría. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Teresa Del Rosal Rabes. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Fernando Baquero Artigao. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Talía Sainz Costa. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Luis Alfonso Alonso García. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Carlos Grasa Lozano. Paediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario La Paz. Madrid, Spain.

Previous meeting: This study was presented as an oral communication at the 69th Congress of the Asociación Española de Pediatría, June 1–3, 2023, Granada, Spain.