In the present work, we present an overview of the contents of the communications presented at the Second National Congress of Paediatrics, held in San Sebastian in 1923, on the occasion of the 100th year anniversary.

The problem of infant mortality stands out as a common thread, which in those years was very high in Spain and was a concern of politicians, intellectuals and the medical profession.

It is worth noting that some of the proposals and concerns of the paediatricians who attended that congress continue to be relevant today.

En el presente trabajo se presenta una aproximación a los contenidos de las ponencias del II Congreso Nacional de Pediatría, celebrado en San Sebastián en 1923, con ocasión del centenario del mismo.

Se destaca como hilo conductor de las mismas el problema de la mortalidad infantil que en aquellos años era muy elevada en España y era una preocupación de políticos, intelectuales y de la clase médica.

Se constata que alguna de las propuestas y preocupaciones de los pediatras que asistieron a dicho congreso siguen vigentes hoy en día.

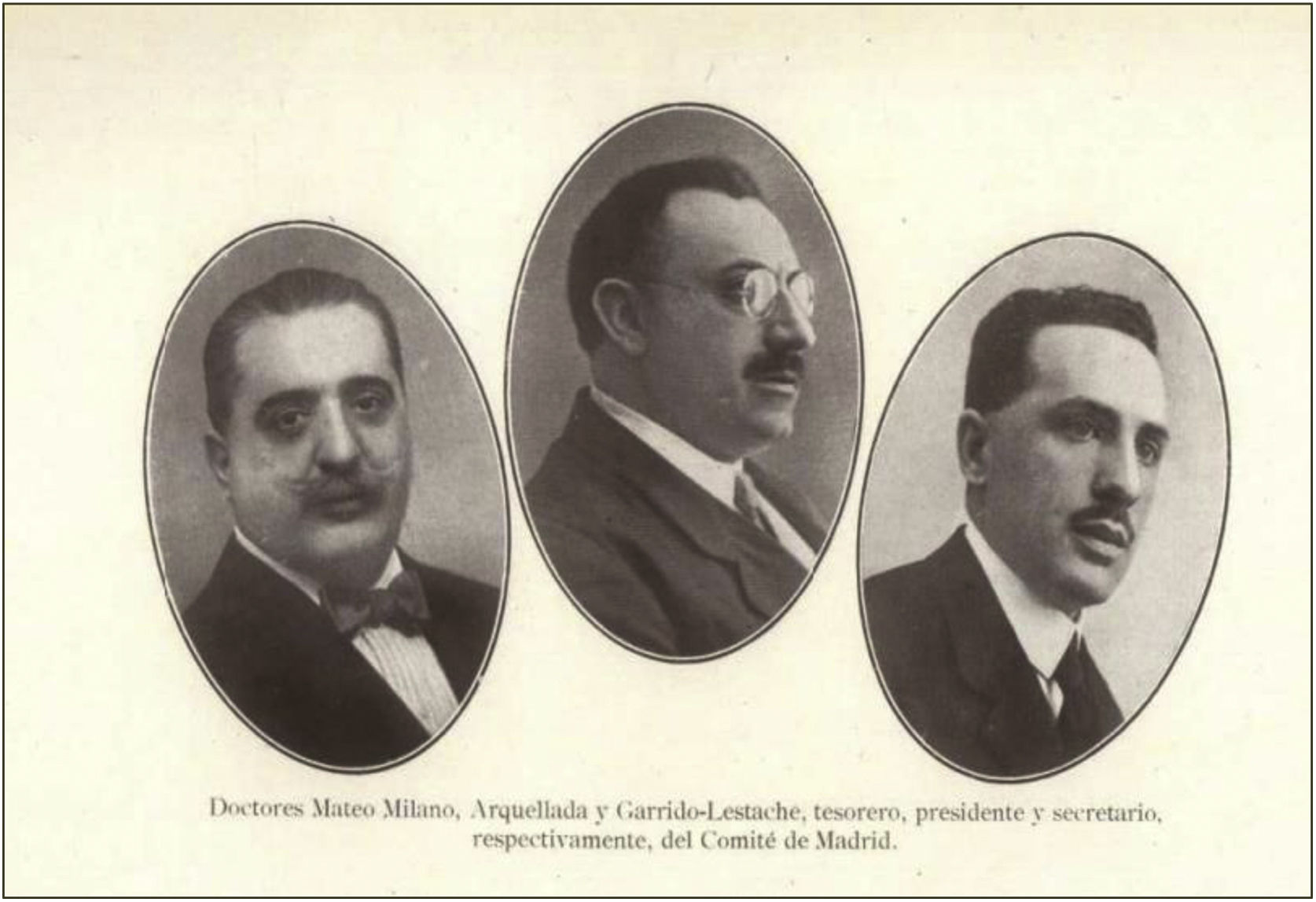

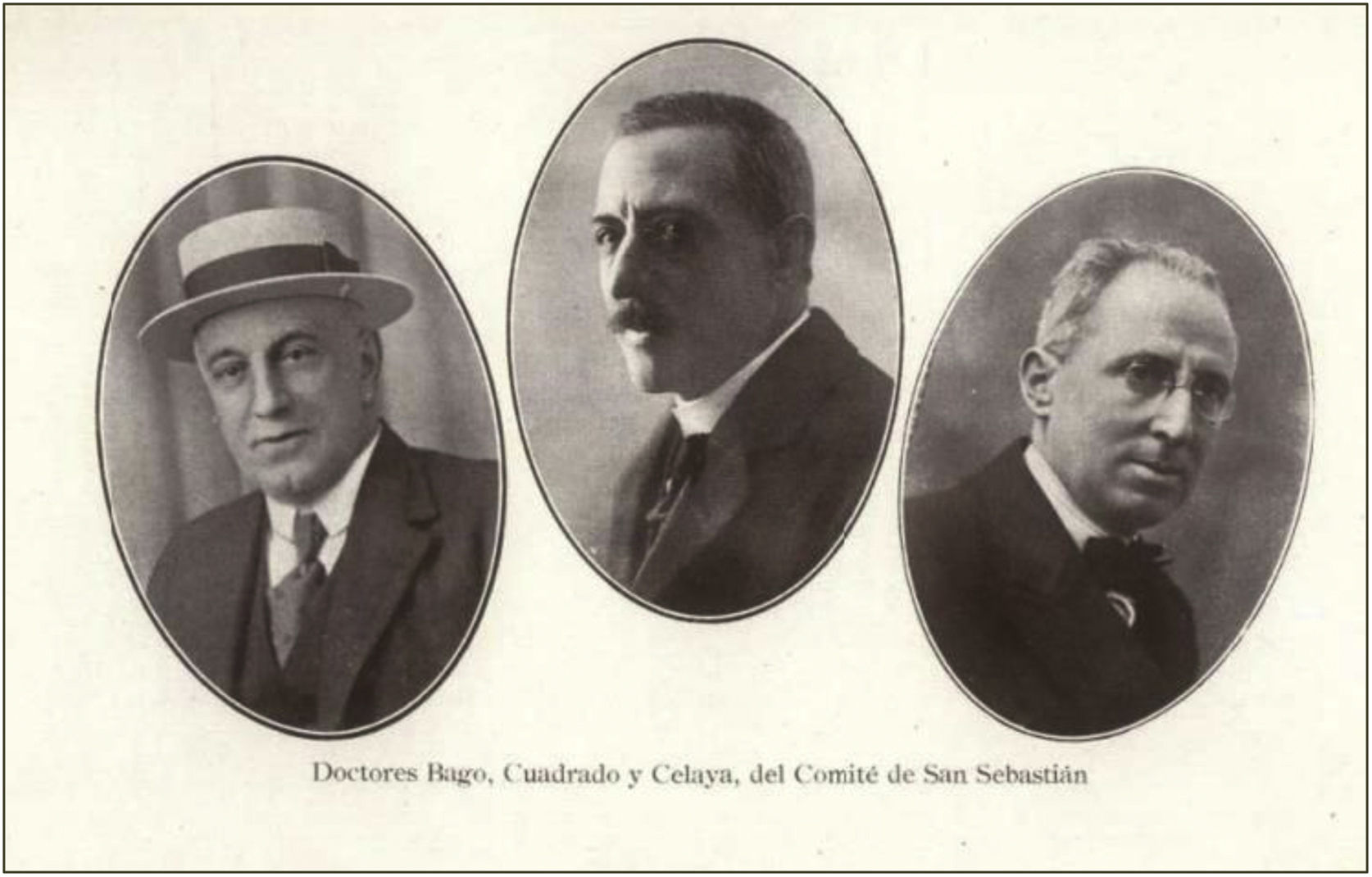

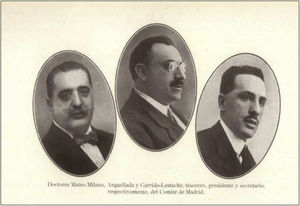

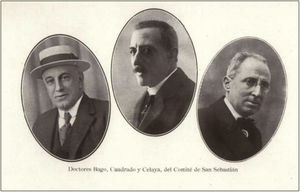

The Second National Congress of Paediatrics in Spain took place between September 2 and 7, 1923.1 These days preceded the turbulent start of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (September 13, 1923). The previous congress had been held in Palma de Mallorca in 1914.2 The delay was due, in part, to World War I, which took place between 1914 and 1918. The president of the Organising Committee of the congress was Dr Aurelio Martín Arquellada, Chief of Orthopaedic Surgery of the Hospital del Niño Jesús of Madrid, who took the helm after Andrés Martínez Vargas, Chair of Paediatrics of Barcelona, and organiser of the first congress. Alongside him, the Committee of Madrid was composed of Matero Milano, treasurer, and Garrido-Lestache, secretary (Fig. 1). In addition to the organisers in Madrid, the participation of physicians from Gipuzkoa was notable, with the establishment of a local committee formed by Drs Bago, Cuadrado y Celaya (Fig. 2), who also oversaw the administrative offices of each of the congress sections.3

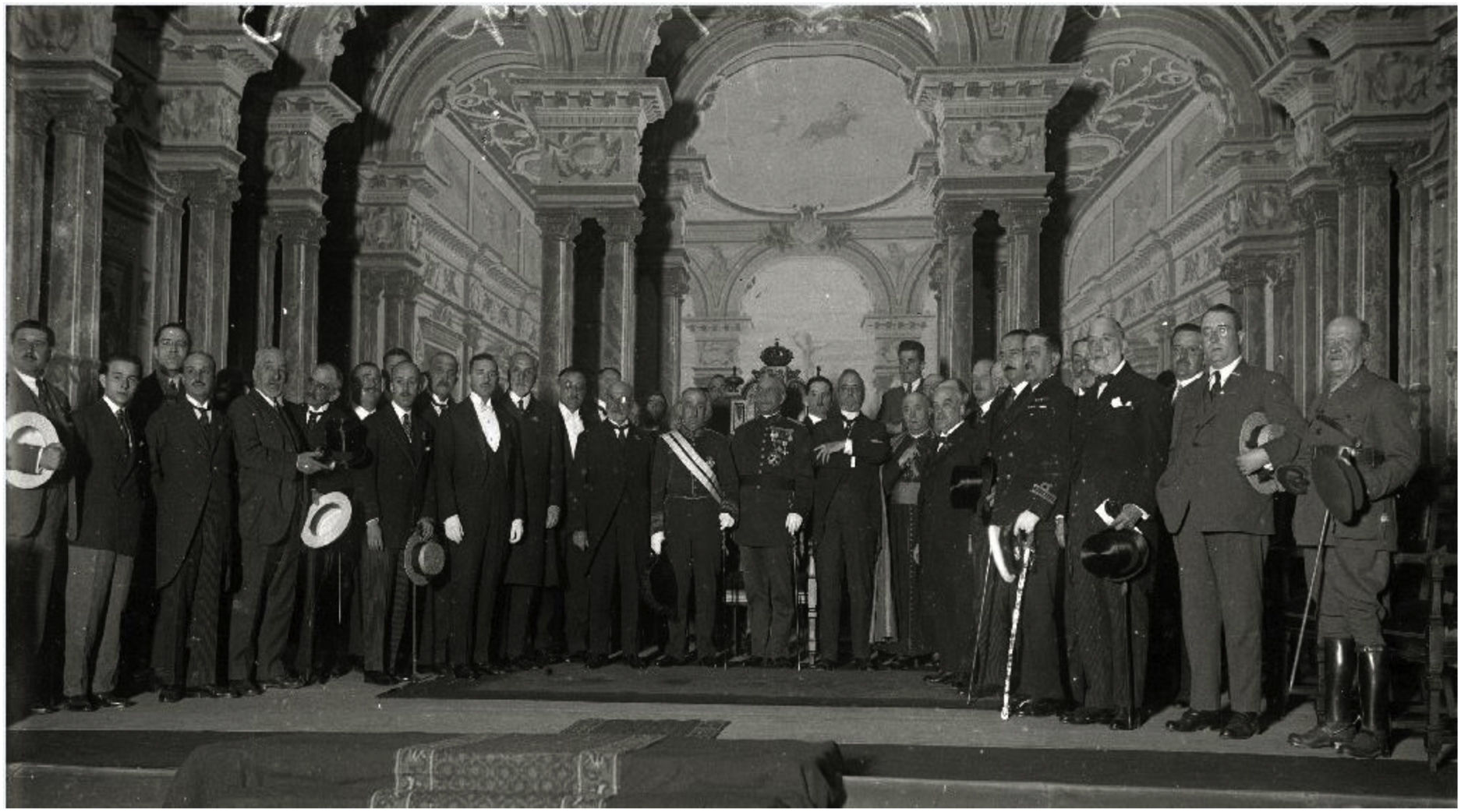

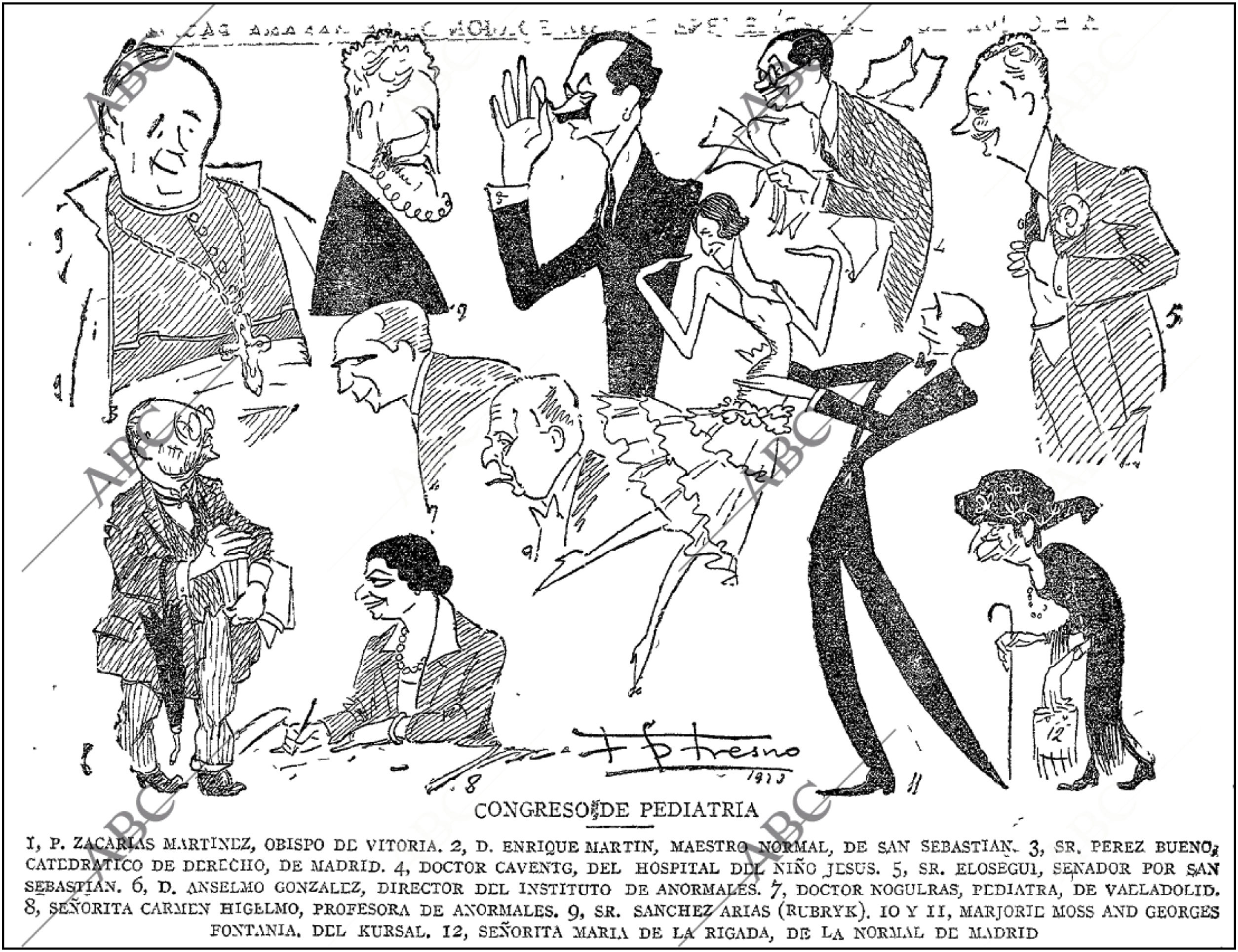

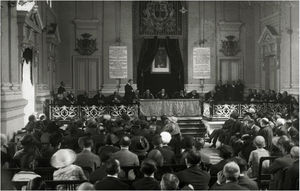

The opening ceremony was held at 11 in the morning in the Teatro Victoria Eugenia. The ceremony was presided by the captain general of the region, Mr Moltó, representing the king, and accompanied by the civil governor, the Marquis of Linares, the mayor, Mr Azcona, the military governor, Mr Querol; the priest of the diocese, Father Zacarías Martínez; the Marquis of Tenorio; and Mr Elósegui, Mr Aldecoa, Mr Pérez Moso, Mr Sánchez Guerra and several physicians. The civil governor, Dr González Álvarez, Mr Martínez Vargas, Dr Arquellada, Mr Sánchez Guerra, mayor Azcona and Mr Pradera spoke at the inauguration (Fig. 3).

On the same day, at 10:30 in the evening, a reception in honour of the congress participants was held at city hall, where dinner was served by the Aero-Club. The authorities and prominent figures of the Congress that had attended the opening ceremony in the morning gathered in the great hall. The mayor and councilmen were in attendance hosting the gathering (Fig. 4).

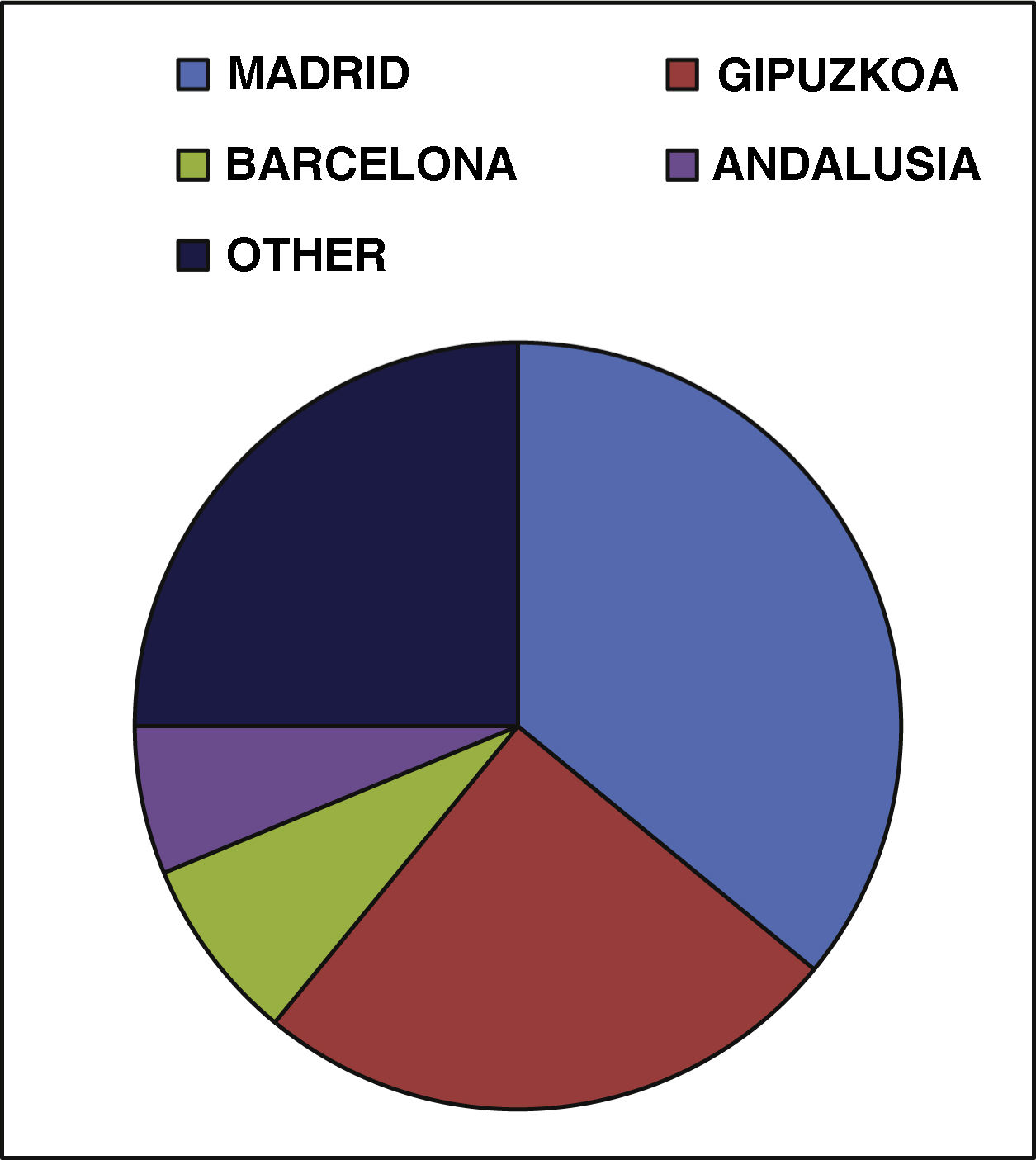

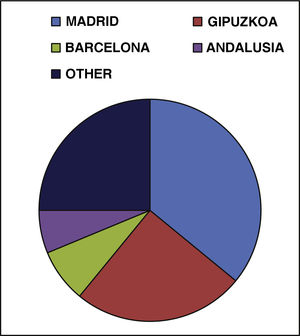

The Congress was structured into 5 sections: Hygiene of the Child, Paediatric Medicine, Paediatric Surgery and Orthopaedics, Child Protection and Pedagogy. It would have been too time consuming to detail the entire calendar of activities of the congress, which was substantial. Instead, to offer an overview of its scientific activities, we picked a common thread, the fight against child mortality, that traversed the activities of most sections of the congress and was consistent with the motto chosen to represent the overall event: “For children and mankind”. There was also substantial participation of physicians and paediatricians, numbering 320 in total. The majority were from Madrid, followed in frequency by those from Gipuzkoa, Barcelona, Andalusia, Zaragoza and Valencia (Fig. 5).

Child mortalityThe greatest concern of paediatricians and society at the time was the high child mortality which, in addition to being a health problem, was perceived as a loss of human capital for the country.

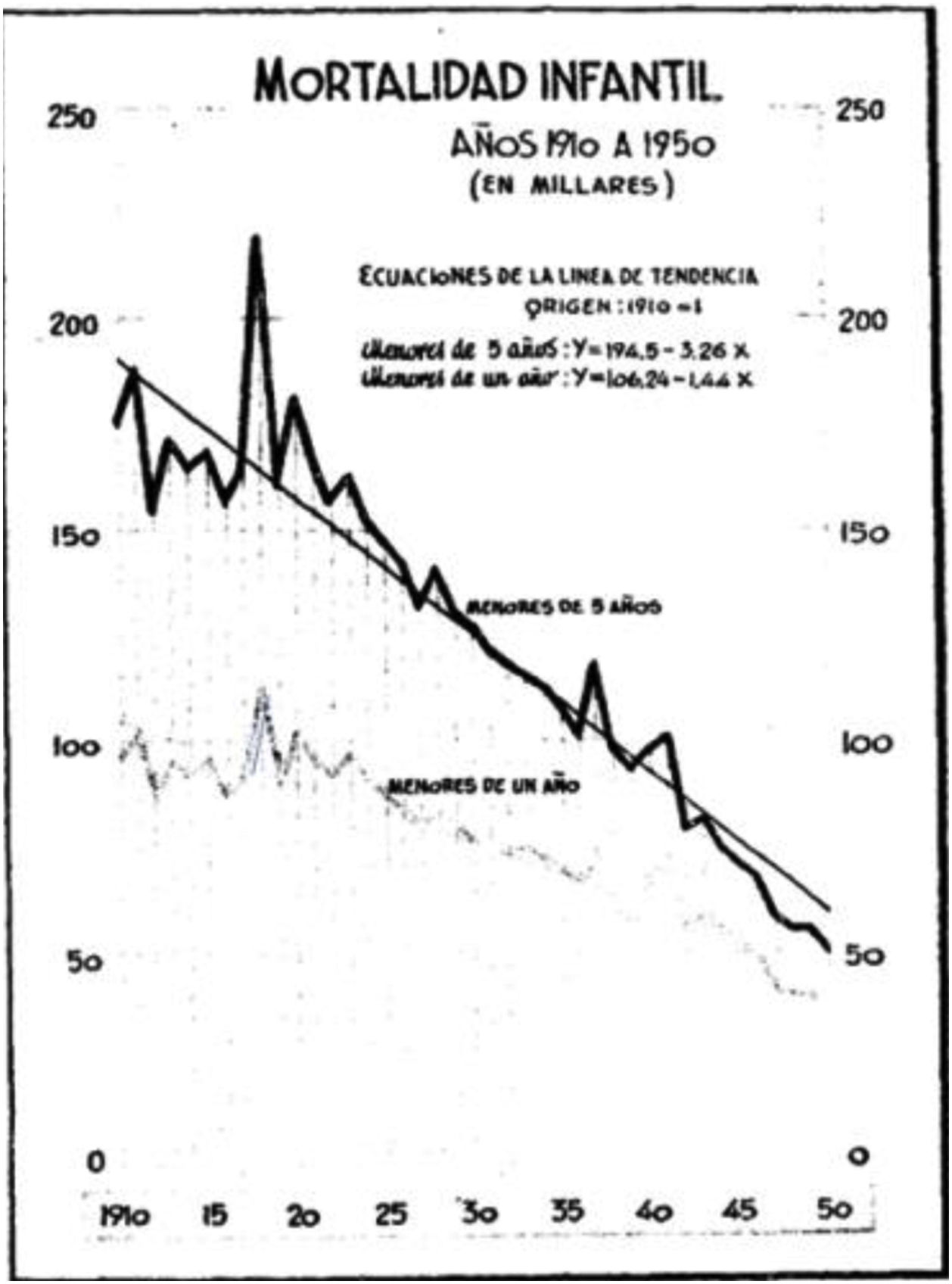

Based on the documentation conserved at the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (National Institute of Statistics), infant mortality in Spain in the 1920s was of 20%.4 For instance, in 1923, for every 100 live births, the mortality was 24.67. Fig. 6 shows the temporal trends in mortality documented in this report. These data do not include foetal deaths, stillbirths and neonatal deaths within 24h of birth. Excluding the spike observed in 1918 corresponding to the flu pandemic, the chart shows a gradual decreasing trend, with mortality reduced by half by the 1950s.

It was not only health care professionals, but also society overall that was greatly concerned about the issue. We may recall, for example, the talk given by journalist Eduardo Navarro Salvador, who, in an article titled “Saving children and our race” stated that the subject that should most concern every congress attendee and even every Spanish citizen, on account of its fundamental nature, was neonatal mortality, and also child mortality, and he continued thus: “Since the turn of the century the curve of births, in terms of live births, has been decreasing, giving rise to a cumulative loss, for this time period, that amounted to millions of babies, who did not come to be in this world. Just as live births decrease year after year, stillbirths increase unnecessarily, and the curves representing this demographic phenomenon exhibit an increasing trend that becomes steeper by the day evincing a rate that, regrettably, is accelerated in the extreme. And, leaving out those born dead, who already number in the thousands in Spain, each year approximately 200 000 children die.”5

In addition to society overall, this concern was manifested in the Congress. One of the lectures was titled “Means to reduce child mortality”.6 It was given by Rafael Tolosa Latour, brother of Manuel Tolosa Latour (1857–1919), who was one of the driving forces, along with Ángel Pulido (1852–1932), behind the Law on Child Protection (1904), the first of the kind in Spain. Rafael Tolosa was a paediatrician in the Instituto Municipal de Puericultura (Municipal Child Care Institute) of Madrid (1923) and was the vice-president of the Sociedad de Pediatría de Madrid (Society of Paediatrics of Madrid) in 1927.7

There was also an oral communication given by Dr Argüelles Terán, titled “The mortality of children in Spain and efficacious methods to reduce it”. This communication had received the Tolosa Latour award of the Consejo Superior de Protección a la Infancia (Superior Council of Child Protection), but was not published in the minutes book of the Congress, except for its conclusions, on account of its length. Among its conclusions, we may highlight his call for “developing policies to protect motherhood in the last 3 months of pregnancy in employed mothers, creating hygienic municipal milk banks, establishing the role of child visitors, promoting breastfeeding through age 3 years, creating schools for mothers, providing prophylaxis for infectious diseases and protecting children at every stage and using every possible means by developing laws to prevent child abuse and child labour”.8

Health care professionals conceived of the fight against child mortality as a continuum spanning from health education prior to conception to the care of the offspring in early childhood, as can be seen below.

Health educationConsistent with the worldview of the time, health education was chiefly aimed at girls, who in the future would be mothers and responsible for the care of children. Thus, Gerardo G. de la Revilla gave a lecture titled “The urgent need to organise schools for child care and sexual education in the fight against child mortality”, in which he stated “Our women, as too our girls, who in time will become women, must be educated, taught all they need to know to become true mothers, aware of their awesome mission of Love and Humanity. It will be the most sublime, most beautiful and most fruitful enterprise the State could ever undertake.”9

Prenatal careToday, pregnant women undergo numerous check-ups, a model of care that was also contemplated a century ago. Doctor Julián Lugunar proposed an intriguing concept that he termed “intrauterine childcare”. He wrote: “The practice of childcare, in my opinion, constitutes a dual medical and social issue, and there is a reason for this, as the foetus dwelling in the womb cannot directly receive the benefits of hygiene or of medical treatment; every intervention on the foetus must be delivered, by necessity, through the mediation of the maternal organism”. In consequence, he proposed the surveillance of pregnant women, a leave from work at the end of the pregnancy and the protection of future mothers from exposure to toxic substances.

Perinatal carePerinatal mortality was substantial. Deliveries were managed in the family home and, if complications arose, the death of the infant and the mother were both commonplace. Doctor Francisco Apaolaza Azcárate, in a communication titled “Reducing mortality protects children”, proposed the creation of small maternity clinics in each territorial division within each province to bring obstetric care closer to families and thus decrease perinatal mortality.10

A text written by Pío Baroja about his medical activity narrates his management of a delivery in a farmhouse in Cestona and the anguish experienced by anyone involved in a childbirth in those years. He tells “The doctor did his examination, asked for hot water and gave orders to the women that accompanied him, telling them what they had to do. The woman was placed on the bed. […] There were ouches […], screams of pain […], irate protestations, grinding teeth […], a pause […], then a terrifying, heartrending shriek […]. The torment had come to an end; but the woman was a mother, and, forgetting her pains, asked, dispiritedly: Dead? No!, no, that mound of flesh was alive, it breathed.”11

Infancy and lactationBreastfeeding was essential in those years. While today we promote breastfeeding as the optimal nutrition for the child, a century ago the inability to feed breastmilk to the child could result in the infant’s death. This is why paediatricians at the time perceived breastfeeding as a woman’s duty. This is how Arístegui spoke of the subject “Ninety-eight percent of mothers can and must breastfeed their children, which is not to say they are able to feed them exclusively with their own milk, but, scarce as it may be, their breast milk offers huge advantages that must not be squandered. Artificial feeding, which is always difficult, is hazardous for the child, especially in the early months, even if all precautions are taken; if precautions are not taken and it is also a warm season, the child is sure to succumb.”12

Some initiatives were proposed to promote breastfeeding, like the one pursued by paediatricians Julio Mariana Larruy and Alejandro Frías Roig, from Valencia and Reus, respectively, who in a communication titled “Mandatory set-up of rooms for breastfeeding infants in every factory and workshop employing married women” advocated for promoting breastfeeding in the first months of life among working mothers.13

ChildhoodThere are two main aspects to consider in this period of development: nutrition and disease prevention. One important intervention implemented with the aim of improving nutrition was the establishment of school canteens. This subject was broached by Mrs Matilde García del Real, a school inspector in Madrid. The participation of women was very limited. While there was one woman who brought up a clinical problem, the few female participants gave presentations on subjects related to education.14 Matilde García del Real explained that the purpose of these facilities would be to provide healthy and nutritious food, but not only that: “The canteen must not be confused with an eating house or a restaurant. In school, home of the child, the canteen is a place of family meals, with all their warmth and moral and educational spirit.”15 Only one woman presented on a clinical subject. She was the ophthalmologist Elisa Soriano Fischer (1891–1964), who spoke on “Trachoma and the school”.16,17 This Congress opened the doors to the participation of female paediatricians, pedagogues and lawyers/jurists that would participate in future gatherings.18 In this period, there was significant gender bias in the medical discourse, so that many diseases and hygiene problems were attributed to the ignorance of women.

As regards health promotion, tuberculosis ravaged the paediatric population, and vaccination was starting to be provided with two different vaccines, bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine and the anti-alpha vaccine developed by Ferrán. A lecture on the subject was given in San Sebastian for the general public that, due to the absence of Dr Ferrán, was read by Dr Pulido: “Child mortality in relation to pre-tuberculous and tuberculous manifestations”. Doctor Pulido discussed the research carried out by Dr Ferrán over the course of 25 years in clinics in America and several cities in Spain, where he had conducted trials on several thousand individuals. He said that, thanks to the work of bacteriologists, among whom Dr Ferrán held a prominent place, the death of thousands of soldiers could be avoided during the Great War, and an epidemic prevented that would have been a veritable catastrophe for European nations. He noted that “The Argentinian Republic has presented a bill in Parliament aimed at making vaccination with the anti-alpha vaccine of Dr Ferrán mandatory, as a means to prevent tuberculosis.”19

The controversy between the proponents of the BCG vaccine and Ferrán’s anti-alpha vaccine was unremitting in Spain and Latin America during those years. In the 1920s, the use of the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis spread throughout the world. But in Spain, as we just mentioned, the tuberculosis vaccine was subject to controversy from the outset. The BCG vaccine had to compete with the vaccine developed by Ferrán. The anti-alpha vaccine was composed of alpha and epsilon bacilli, both of which were non-acid fast. Epsilon bacilli were obtained from pure cultures of Koch bacilli. Ferrán sought to vaccinate those in the pre-tubercular stage against infection. He used his vaccine in Alzira, administering 14 000 doses, without incident. In Alberique (Valencia), 3500, and in Palma de Mallorca, 1500. After 8 years, he had vaccinated a million individuals. But the BCG was not forgotten. The vaccine developed by Calmette was introduced in Spain in 1924 by physiologist Lluis Sayé, director of the anti-tuberculosis clinics of Catalonia and who opposed the use of Ferrán’s vaccine; in 1933 he had performed 10 000 vaccinations. A Royal Order issued in 1927 recommended the use of anti-alpha vaccine in public health care facilities and charities, yet, in the Anti-Tuberculosis Clinic of Madrid, both vaccines were used, as chosen by the parents. The death of Ferrán in 1929 and the greater efficacy of the BCG vaccine resulted in a decreased use of the anti-alpha vaccine, and, in 1931, the government decided to recommend the BCG vaccine.”20

Mr Gregorio Marañón wrote: “Why did the brilliant idea of a great Spaniard end thus, incomplete? Because already, in Ferrán’s time—all the more so now—a scientific work cannot be the product of one human mind, even one of utmost brilliance and scientific prowess. Bacteriology was, in the times of Ferrán, an activity that demanded of him what he could not have: a group of collaborators, a field.”21

Many other subjects were addressed in the Paediatric Medicine section, all of great interest, but due to length constraints, we cannot describe them in detail here.

Other aspectsIn this brief overview of the activities of the Congress, we omitted the third section, corresponding to Surgery, and the fifth section, to Pedagogy, which were also related to child care and rearing.

In regard to the first one, we ought to highlight the main lecture given by Dr José Blanc Fortacín, of the Hospital de la Princesa in Madrid, who broached the subject of “Gynaecological diseases in childhood”.22 He discussed ovulation disorders, nonmenstrual bleeding in prepubertal girls and infectious diseases that were common at the time (measles or scarlet fever) that could involve the vulvar or vaginal mucosas or the internal genital organs. He described several cases of vulvar gangrene in the context of scarlet fever and erysipelas. He also explained the treatment of urethral prolapse or vaginal tumours and one case of severe haematocolpos due to an imperforate vagina in a girl aged 13 years. Thus, he offered a complete and up-to-date overview of genital disorders in girls and female adolescents.

The fifth section is somewhat marginal from the current perspective, as pedagogy and paediatrics are now separate fields, but at the time the Congress sought to comprehend every aspect related to the care and rearing of the child, and the school was an essential component of it.

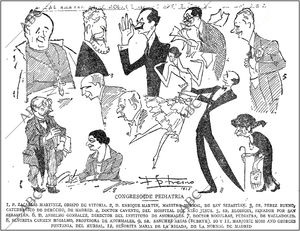

Last of all, we present a cartoon of some of the congress attendees, drawn by caricaturist Fernando Gómez-Pamo del Fresno (1881–1949) and published in the newspaper ABC, which, as can be seen, he signed as F. G. Fresno (Fig. 7).

Closing ceremonyThe closing ceremony took place in the great hall of the Instituto Peñaflorida. It was presided, in the name of the king, by the minister of Education, Mr Salvatella. To his right were the bishop of the diocese, father Zacarías Martínez; the president of the congress, Dr Arquellada; the president of the provincial council, Mr Elorza, and senator Elósegui. To his left were the mayor, Mr Azcona; the director general of Public Health, Mr Martín Salazar, and Dr Ricardo Royo Villanova (Fig. 8). The secretary general of the congress, Dr Garrido-Lestache, read the agreed conclusions, which can be found in the Appendix.

To conclude, it is worth highlighting the closing reflections of the lecture given by Dr Rafael Tolosa Latour, summarising the bulk of the activity of the Congress: “The ideal goal would be for physicians not to have to cure, because the elements of the life in which children are born and start to develop are conducive to viability, for practitioners to have to intervene only in exceptional cases. In this regard, the responsibility rests with lawmakers and hygienists. It is society, the universal brotherhood of humanity, that must do the work. Let mothers be protected during pregnancy and in childbirth and in the weeks that follow; let unions form between young, healthy and strong persons; may restrictive laws be enacted against alcoholism and prostitution; may all enjoy sufficient fresh air and light, and be availed in their homes of all the comforts that keep those who live there in their dwellings; may nourishment be plentiful because the price of food is moderate. It is, therefore, the action of the collective that can improve the living conditions of children, which is, in the end, improving Humanity.”6 Today, many among us would sign our names under these wishes of Dr Latour.

Conclusions of the CongressThe Secretary General of the Congress, Dr Garrido Lestache, presented the approved conclusions drawn from the lectures, which were the following:

Section I. Hygiene and nutrition of the child- 1

Breastfeeding must be boosted, facilitating it through the moral and material support of mothers with the creation of institutions whose ultimate purpose is the education of mothers and the observation and surveillance of children.

- 2

The establishment of child care institutions must be pursued, as they are most suitable for the instruction of mothers and as a milieu for the prophylaxis and cure of gastrointestinal ailments.

- 3

The authorities must rigorously ensure the absolute purity of the milk used to feed children.

- 4

The State and the Municipalities must promote the creation of gardens and parks for children.

- 5

Child Care chairs must be created in every Normal School.

- 1

Having discussed every aspect of paediatric medicine, this delegation considers that it is of utmost importance to society that public authorities organise the fight against diphtheria through active immunization and other means currently recommended for prophylaxis.

- 2

Recommend the reform of the current regulation of foundling hospitals. The relationship between mother and child should be facilitated, allowing mothers to move from maternity clinics or hospitals to the Foundling Hospital and to stay there for as long as necessary to ensure the survival of the child, through natural breastfeeding.

- 3

Endow foundling hospitals with auxiliary staff, adequately educated and trained on the practices of modern child care and with an official degree qualifying them to provide direct care to children, in order to ensure the indispensable aseptic environment in these facilities.

- 4

A single administrative body, led by physicians, to govern the health care services provided in these institutions; towards which the other valuable elements that form the existing foundling hospitals will collaborate under its leadership.

- 5

To adhere fully and strictly to the Law on Child Protection.

- 1

We call for the creation of Orthopaedic and Pedagogic institutions for children with locomotor deficiencies where, in addition to providing surgical and nonsurgical treatment, their literacy and general knowledge can be tended to, their ability to work assessed, and professional training provided. This would make it possible to rightfully demand the abolition of the shameful mendicity of cripples.

- 2

Courses on Orthopaedics must be organised in Colleges and unqualified practice in the field should be considered actionable.

- 3

Given the importance of the integrity of the dentition in relation to the health of the individual, Dental Clinics must be created.

- 4

We propose to the Board of the Congress that one of the subjects in the next Congress be “The diagnosis and treatment of spina bifida occulta”.

- 1

The information contributed by medical inspectors of schools in Madrid once again demonstrated the efficacy of the Medical Inspection of Schools and the need to expand it and extend it to all of Spain.

- 2

For this Inspection to be, as it should be, as biologically broad as possible, it requires the constant, close, and cordial collaboration of physician and teacher, the former of whom is in charge of the pathological and developmental part of this Inspection, but with mutual aid.

- 3

To carry out this function in large towns, specialised school physicians must be appointed. In small municipalities, this duty will be fulfilled by general practitioners.

- 4

To prepare staff for performing school inspections, the necessary courses of study will need to be created in the Schools of Medicine and Normal Schools. While this is not possible, trainings should be organised periodically for physicians and teachers who wish to specialise in medical inspection.

- 1

The challenge of educating the handicapped is a pressing issue the resolution of which is indispensable to achieve:

- a)

Adherence to the legal mandates on compulsory education.

- b)

Adequate organization of education for the handicapped.

- c)

Efficacy in invested efforts toward remedying social parasitism.

- a)

- 2

Therefore: in any graded school affiliated to a normal school, there need to be a sufficient number of grades and forms to provide adequate education to the various categories of handicapped children. The number of classes or forms devoted to them will not be fixed or the same in every place at every time, but variable based on the conditions of the time and place.

- 3

It is absolutely necessary to separate, when it comes to handicapped children, the task of child care from the task of education. The first is the responsibility of charities, the second, of teachers.

- 4

Within general charities, special departments must be founded for children to operate as home-schools, to educate those referred to as severely subnormal, that is, the extreme, most pathological forms of subnormality.

- 5

These departments may also be created in Homes and Hospitals where there are children with handicaps of the locomotor system or caring for children with trachoma or other diseases requiring prolonged medical care during childhood.

The National Congress on Paediatrics expresses a desire to do away with the turnstile in children’s homes, which in Spain is still used to admit abandoned children. This measure, far from promoting infanticide, as proposed by the old guard, opposes the outward or hidden and surreptitious crime of amoral individuals or hypocrites, as confirmed by every nation of the world.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.