Suicidal behaviour and self-harm are increasing in children and adolescents. Non-suicidal self-harm are a dysfunctional method of emotional regulation, and it must be distinguished from suicidal behaviours.

MethodsNarrative review of the current situation on suicide and self-harm in Spain. Descriptive study of suicidal behaviours in paediatric emergencies.

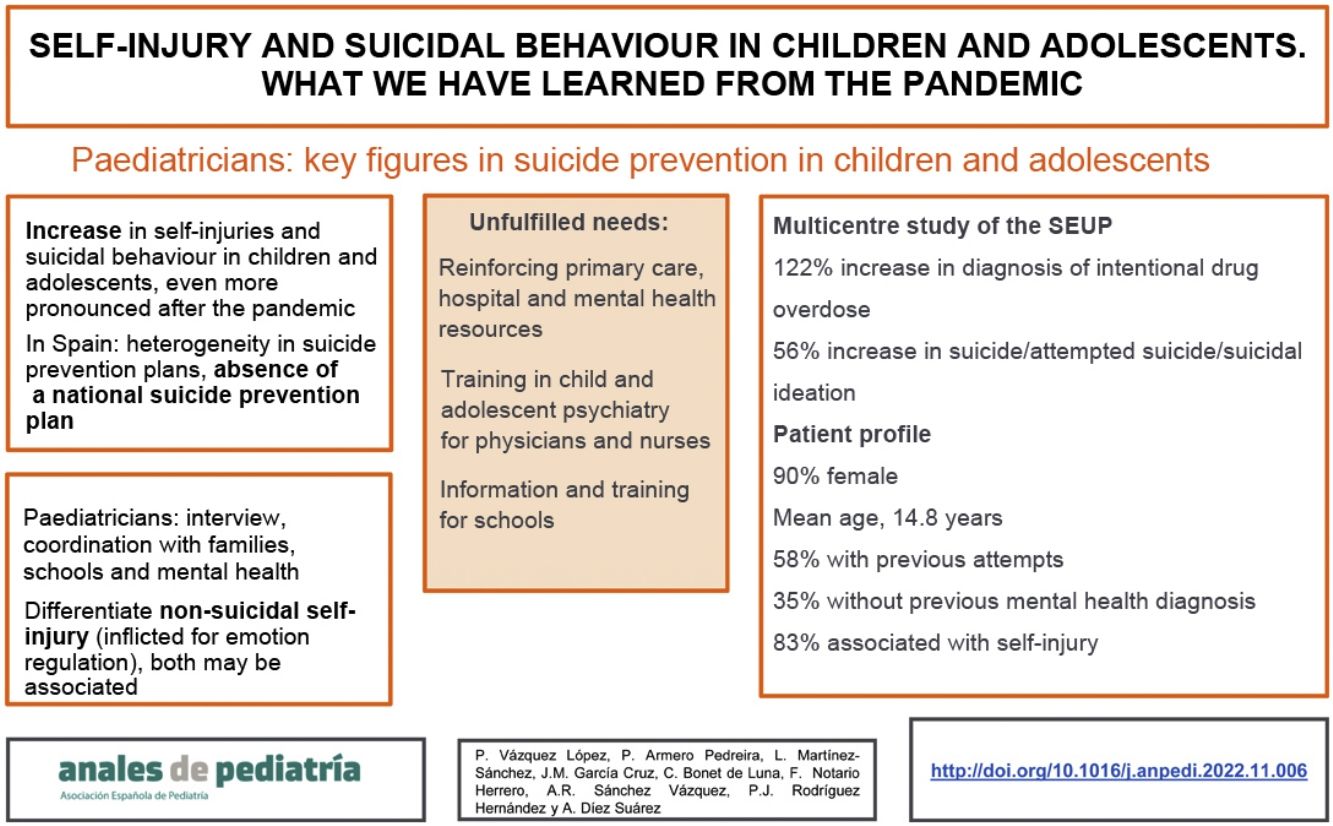

ResultsMental health consultations were analysed (March-2019 to March-2020 and March-2020 to March-2021) in a multicentric study of the SEUP (Spanish Society of Pediatric Emergencies), finding a 122 % increase of the diagnosis of "non-accidental drug intoxication” and 56 % of “suicide/suicide attempt/suicidal ideation”. In another prospective analysis, 281 attempts were recorded, with the patient profile being: female (90.1 %), 14.8 years old, 34.9 % without previous psychiatric diagnosis; 57.7% with previous suicidal behaviour. The presence of psychiatric disorders, especially depression, and previous attempts, are the best-known risk factors for suicidal behaviour, although other factors are involved (family, personal or social). Pediatricians should be trained to deal with questions about suicide and acquire the skills to conduct an interview with a supportive and empathetic attitude. In Spain, suicide prevention plans are heterogeneous among communities, and there is not a unified national suicide prevention plan.

ConclusionsPrimary, hospital and mental health care resources for paediatric population should be strengthened to prevent suicidal behaviours. Specific training for school staff, and child and adolescent psychiatry training for paediatricians and nurses are crucial in the prevention of suicide in children and adolescent population.

Las conductas suicidas y las autolesiones están aumentando en niños y adolescentes. Las autolesiones no suicidas suponen un método disfuncional de regulación emocional. Es importante aprender a distinguirlas de las conductas suicidas.

Material y métodosRevisión narrativa de la situación actual sobre suicidio y autolesiones en España. Estudio descriptivo conductas suicidas en urgencias pediátricas.

ResultadosEn un estudio multicéntrico de la SEUP (sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas) se analizaron las consultas por salud mental (marzo-2019 a marzo-2020 y marzo-2020 a marzo-2021), encontrándose un aumento de 122% del diagnóstico “intoxicación no accidental por fármacos” y de 56% en “suicidio/ intento de suicidio/ideación autolítica”. En otro análisis prospectivo, se registraron 281 tentativas, siendo el perfil de paciente: sexo femenino (90,1%), 14,8 años, 34,9% sin diagnóstico psiquiátrico previo, 57,7% con conductas suicidas anteriormente. La presencia de trastornos psiquiátricos, en especial de depresión, y de intentos previos, son los factores de riesgo más implicados en la conducta suicida, aunque existen otros de índole diversa (familiares, personales o sociales). Los pediatras deben estar formados para atender consultas sobre suicidio, y adquirir habilidades para realizar una entrevista con actitud de apoyo y empatía. En España los planes de prevención de suicidio son heterogéneos y no existe un plan nacional de prevención del suicidio.

ConclusionesSe deben reforzar los recursos de atención primaria, hospitalaria y de salud mental de población pediátrica. Los centros escolares y la formación en psiquiatría infantil y adolescente para médicos y enfermeras resultan cruciales en la prevención del suicidio en niños y adolescentes.

In the past few years, and especially since the beginning of the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, there has been evidence of a deterioration of the mental health of children and adolescents. In particular, adolescents are exhibiting more depressive symptoms, self-harm and suicidal behaviours. This is an alarming situation and has become an important public health problema, especially after the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.1–3 In 2020, the Fundación de Atención de Niños y Adolescentes en Riesgo (ANAR, Foundation for the Care of At-Risk Children and Adolescents) received 145 % more calls from minors with suicidal ideation or who had attempted suicide, and the frequency of self-injuries increased by 180 % relative to the two previous years.3

In 2020, 14 children under 15 years committed suicide, double the number of the previous year, and the trend is worsening.4 In youth aged 15–29 years, suicide is already the second leading cause of death, only exceeded by malignant tumours.4–6 This increase in both the number of completed and attempted suicides, chiefly through the intentional drug poisoning,2,3,7,8 was identified as early as 2010.7

Beyond the realm of statistics, suicidal behaviour has a significant impact and is associated with a relevant degree of stigmatization, even discrimination, that hinders and complicates its management and prevention. Self-harm and associated suicidal behaviours have a short- and long-term impact not only in the life of the individuals that engage in them, but also on their family and social environment. Due to all of the above, there is a pressing need for tools allowing early detection in clinical practice. In addition, the approach to their management must be holistic, and interventions must include a community-based and public health component, including primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies.9 Paediatricians are one of the professional collectives most involved in this process, so it is crucial that they be sufficiently trained on the subject.

Self-harm and suicide attemptsSelf-harm refers to behaviours aimed at inflicting some form of physical injury on oneself. These behaviours are not always associated with suicidal ideation or intent. Self-injurious and suicidal behaviours may occur in the same person simultaneously or at different times. It is crucial for professionals to be able to discriminate between non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal behaviour, so they must receive adequate training, and should not avoid discussing or bringing up these subjects.9

Non-suicidal self-injury is defined as the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue10 (Table 1). In addition to cutting, the most frequent behaviour, it may involve biting, burning, scratching or excessive rubbing, hitting or any other way to harm oneself, without the intent of ending one’s life. The underlying motivations attributed to these behaviours are that they serve as means to dampen or alleviate negative feelings, to punish oneself or to seek social positive reinforcement.11,12 All these possibilities must be considered, attempting to make the adolescent feel understood, avoiding judgmental or critical attitudes. These are some examples:

Relief or reduction of negative feelings: when feeling intense anxiety or distress, patients may engage in NSSI to “replace” emotional pain by physical pain.

Self-punishment: when feeling guilt, NSSI may be perceived as a form of compensation.

Need of social positive reinforcement: with the aim of causing a change in their environment, patients may engage in NSSI, either to draw attention away from other situations or to avoid situations that they feel unable to confront (for instance, if they do not want to go to school, they expect they would not be forced to go) or to receive more attention from another person (for instance, after a breakup, or if they feel ignored by parents).

Proposed criteria for non-suicidal self-injury in the DSM-5.

| A | In the last year, the individual has, on 5 or more days, engaged in intentional self-inflicted damage to the surface of his or her body of a sort likely to induce bleeding, bruising, or pain (e.g., cutting, burning, stabbing, hitting, excessive rubbing), with the expectation that the injury will lead to only minor or moderate physical harm (i.e., there is no suicidal intent). |

| Note: The absence of suicidal intent has either been stated by the individual or can be inferred by the individual's repeated engagement in a behaviour that the individual knows, or has learned, is not likely to result in death. | |

| B | The individual engages in the self-injurious behaviour with one or more of the following expectations: |

| 1. To obtain relief from a negative feeling or cognitive state. | |

| 2. To resolve an interpersonal difficulty. | |

| 3. To induce a positive feeling state. | |

| Note: The desired relief or response is experienced during or shortly after the selfinjury, and the individual may display patterns of behaviour suggesting a dependence on repeatedly engaging in it. | |

| C | The intentional self-injury is associated with at least one of the following: |

| 1. Interpersonal difficulties or negative feelings or thoughts, such as depression, anxiety, tension, anger, generalized distress, or self-criticism, occurring in the period immediately prior to the self-injurious act. | |

| 2. Prior to engaging in the act, a period of preoccupation with the intended behaviour that is difficult to control. | |

| 3. Thinking about self-injury that occurs frequently, even when it is not acted upon. | |

| D | The behaviour is not socially sanctioned (e.g., body piercing, tattooing, part of a religious or cultural ritual) and is not restricted to picking a scab or nail biting. |

| E | The behaviour or its consequences cause clinically significant distress or interference in interpersonal, academic, or other important areas of functioning. |

| F | The behaviour does not occur exclusively during psychotic episodes, delirium, substance intoxication, or substance withdrawal. In individuals with a neurodevelopmental disorder, the behaviour is not part of a pattern of repetitive stereotypies. The behaviour is not better explained by another mental disorder or medical condition (e.g., psychotic disorder, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, stereotypic movement disorder with self-injury, trichotillomania [hair-pulling disorder], excoriation [skin-picking] disorder). |

Diagnostic criteria for non-suicidal self-injury proposed by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2014, p 803.

The prevalence varies between studies and countries, ranging from 15% to 25%, and is greater in the female sex.11,12 Since the 60s, there has been an increase in this type of injuries, especially in adolescents and young adults, and it is a source of growing concern, not only in the health care field but also in the education and in families.12 Although traditionally this type of behaviours have been associated with mental disorders (emotionally unstable personality disorder, eating disorder, depression or anxiety), more recent evidence has shown that they may also manifest in the absence of psychiatric comorbidity. Approximately half of these adolescents also have suicidal ideation and are at higher risk of having suicidal intent and attempting suicide, especially in the case of serious or recurring self-injury.12 Therefore, they are behaviours that need to be assessed by qualified professionals.

As regards suicidal behaviour, it is important to differentiate between, in order of increasing severity, suicidal ideation, suicide threats, suicide attempts and, lastly, completed suicide.7,10 Suicide is a serious public health problem, and the World Health Organization (WHO) considers suicide prevention a global imperative. If affects low-, middle- and high-income countries and individuals, and it is estimated that approximately 70% of the individuals that die of suicide meet the diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder, most frequently depression and bipolar disorder.13

The consumption of alcohol and other substances facilitates acting on suicidal ideation, and access to firearms is also a risk factor. It is estimated that 1 in 10 individuals that attempt suicide eventually die of this cause, and in adolescents and young adults, suicidal behaviours are much more frequent compared to other age groups. The spectrum could be conceived of as an iceberg, with completed suicide corresponding to the tip and suicidal behaviours constituting the more prevalent underlying problem. Intentional drug overdose is the most frequent reason for seeking emergency care related to mental health.13

Suicide attempts in adolescents in SpainThe Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría (SEUP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine) analysed trends in diagnosis related to psychiatric disorders in 16 paediatric emergency departments (PEDs) before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Comparing to the March 2019-March 2020 period, in the March 2020-March 2021 period there was a 122% increase in the diagnosis of intentional drug overdose and a 56% increase in the diagnosis of suicide/suicidal attempt/suicidal ideation.17 Within the same society, the Working Group on Poisoning started a prospective study in 2021 in the paediatric patients that presented in the emergency department following intentional ingestion of toxic substances, with participation of 23 PEDs in 10 different autonomous communities. In the first 9 months under study, there were 281 documented attempts, with a clear predominance of female patients (90.1%) and a mean age of 14.8 years. The most salient finding was that one third of these patients (34.9%) did not have a pre-existing psychiatric diagnosis, which is not to say they did not have any mental health disorders. Another relevant finding was that half (57.7%) had attempted suicide before. In addition to intentional drug overdose, most patients (82.6%) reported engaging in NSSI14,15 (Fig. 1).

Suicidal behaviour triggers, risk factors and protective factorsAdolescents are a vulnerable population due to the physical, emotional and social changes they undergo in addition to their need of autonomy and finding their own identity. Some are also exposed to risk situations, such as abuse or violence.15 Suicidal behaviour is complex and multifactorial, as it is associated with various risk factors and multiple and interrelated causes of a biological, psychological, cultural and socioeconomic nature, all of which may change over time16–20 (Table 2).

Suicide behaviour triggers and risk and protective factors in children and adolescents.

| Individual factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triggers | Risk factors | Protective factors |

| Death or loss of a loved one | Pre-existing psychiatric disorder | Communication and conflict resolution skills |

| Ending of friendship or romantic relationship | Previous suicide attempt | Being able to seek help (information and access) |

| Home confinement during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic | Female sex | Good emotional regulation and self-concept |

| School bullying (bullying or being bullied) | Adolescence | Prosocial beliefs and values |

| Abuse, mistreatment and trauma | Difficulties with peers | Resilience |

| Difficulty expressing feelings | Perceived control | |

| Loneliness | Restricted access to lethal substances and devices | |

| Poor impulse control, low frustration tolerance | Exercise and sports | |

| Disease, chronic pain, physical disability | Feelings of belonging (club, social groups) | |

| History of abuse (physical, mental, sexual, school bullying, cyberbullying) | ||

| Unwanted pregnancy | ||

| Access to lethal means | ||

| History of self-injury | ||

| Use of alcohol or other substances | ||

| Non-heterosexual orientation | ||

| Technology abuse and influence | ||

| Family-related factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triggers | Risk factors | Protective factors |

| Family conflict | Family history of suicide | Strong attachment in the family |

| Recent disease or death or loved one | Psychiatric disorder in family | Assertive parenting style |

| Disease in parents | Feeling supported and understood | |

| Domestic violence | ||

| Rupture of family relationships | ||

| Lack of communication in family | ||

| High demands and perfectionism | ||

| Alcohol or substance abuse in family | ||

| Social and school-related factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triggers | Risk factors | Protective factors |

| Suicide in a close person | Absence of social support network | Adequate social network |

| Social and economic disadvantage | Social or cultural uprooting | Positive relationships with adult role models (parents, teachers…) |

| Imitation of suicidal behaviour (mass and social media) | School bullying (victim or perpetrator) | Positive expectations of social, personal and educational development |

| Pandemics | Socioeconomic vulnerability. | Adequate management of leisure and free time |

| Marginalization, isolation | Easy access to health or mental health services | |

| School failure | ||

| Lack of health care and social welfare resources for prevention | ||

The pandemic has evinced the key role of social determinants in increasing the risk of health problems, both physical and mental (emotional and environmental). The main triggers in this period were social isolation, the interruption of daily life routines, the multiple restrictions to leisure activities and an excessive use of screens.16,17,20 In addition, some minors were exposed to disease or even death, precarious work, financial problems or overcrowding in their close environment. In some instances, they may have felt responsible for contagions. Overexposure to information on SARS-CoV-2 combined with great uncertainty in significant adults was associated with an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms. There has also been an increase in domestic violence, and mental health has worsened within families.16,17,20

However, not every adolescent has suffered symptoms of depression or anxiety, or engaged in self-harm or suicidal behaviour. This is because in addition to all these shared factors, there are also individual predisposing factors. The best known for suicidal behaviour are female sex, the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depression, and a history of previous suicide attempts.13 Having made one attempt is associated with a 32-fold probability of death by suicide in the following year, and 1 in 100 youth that attempt suicide will die from this cause in the next 7 years.11 The Save the Children report concluded that minors in households with fewer resources are most affected and are four times more likely to experience mental health problems and engage in suicidal behaviour.18

In addition to trying to reduce risk factors and triggers, the strengths of each adolescent and the surrounding environment must also be taken into account. Social and problem-solving skills, the development and appreciation of the importance of empathy, respecting diversity, tolerating frustration, resilience and emotion regulation are some of the skills that can be taught and could protect from future suicidal behaviour. Families, schools and health care institutions play a key role in this regard. Schools are very important regulators of behaviour in children and youth, and can buffer many sources of stress and anxiety in this age group. A family environment with positive parental roles, interpersonal relationships, sports and predictable routines are also protective factors in relation to mental health and suicidal behaviour.19

We may want to reflect on the fact that Western society is currently framed in the so-called “welfare state”, which is characterised by material abundance but entails a series of affective and emotional deficiencies. The lack of quality time with children, the demands of work, an excessive number of activities focused on performance and efficiency, or the lack of communication or “real” social interactions lead to isolation. In this context, there is a risk to provide education focused exclusively on cognitive goals and neglecting social and emotional aspects. Learning strategies to be able to cope with situations and tolerate frustration, manage conflict or seek help and provide it to others promotes psychological wellbeing and resilience.20,21

Areas of improvementGaps in child and adolescent suicide preventionSpain does not have a national suicide prevention plan, which translates to heterogeneity in the plans for management of suicide risk in different autonomous communities (ACs). Prevention does not depend exclusively on mental health services, the resources involved in suicide prevention in youth are diverse (Table 3), and the current trend can only be reversed with the participation and coordination of all of them.

Resources involved in suicide prevention in the child and adolescent population.

| Medical services: primary care, mental health, hospital-based and out-of-hospital emergency care |

| Police and firefighting forces |

| Education |

| Social and legal services |

| Associations: suicide survivors and individuals affected by suicide, non-governmental organizations, crisis lines, foundations: ANAR, UNICEF, Save the Children etc. |

| Mass media |

The main gaps and limitations detected by the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) on behalf of the collective of paediatricians as regards suicidal behaviour in adolescents are:

Absence or heterogeneity of suicide prevention programmes in different ACs.

Insufficient specific training on mental health and limited resources for professionals in contact with children and adolescents both in the health care field (paediatricians, PC physicians, nurses) and in schools (teachers, school counsellors).

Increasing waiting lists and overwhelming demand in primary care, emergency care and mental health services for adolescents with suicidal behaviour.

Lack of coordination between institutions and levels of care.

The training in mental health of paediatricians, especially in primary care, given their closeness and continuous contact with families, primary care general physicians and nurses, is crucial for prevention, as these are the professionals that provide care to children and adolescents routinely. The AEP advocates for making rotations in child and adolescent psychiatry mandatory for paediatrics residents, which is already required of primary care physicians. In addition, paediatricians and primary care physicians should receive training in mental health, not with the aim of having them all become specialists on the subject, but to acquire the basic knowledge necessary to detect cases and engage in primary and secondary prevention. This can be achieved by means of visiting clinical rotations, continuing education activities, remote consultations or periodic coordination meetings.

In the school setting, training programmes must be developed for the delivery of education on suicide prevention and early detection of suicide risk by specialists in the field to teachers, counsellors and administrators. Working on the development of emotional health and resilience from an early age is essential.

The goals of training in school-based professionals are:

Knowing the risk factors and warning signs associated with suicidal behaviours in children and adolescents and being able to detect them.

Establishing measures for management and follow-up in the case of suicidal behaviour: knowing how to address the behaviour, listen actively and efficiently with a supportive and tactful attitude, and confidentiality issues.

Knowing measures to prevent worsening or potential imitation of a behaviour.

Learning to communicate with families efficiently, tactfully and with ease.

In schools, select and train groups of students to provide support, help detect cases in the school grounds and the social environment, including social networks.

Other professionals involved in suicide prevention are those working in emergency care services and social facilitators (police, firefighters, social workers, etc.).

In 2021, the Ministry of Health approved the Mental Health Action Plan for 2022–2026, which will start to be implemented in upcoming months.22 This document formulated action recommendations structured into 10 strategic lines: “Prevention, early detection and management of suicidal behaviour” is strategic line 3, while “Child and adolescent mental health” is strategic line 5 (Table 4). Other documents, such as the recommendations of the WHO23 or guidelines at the European level like those of the European Alliance Against Depression (EAAD),24 have also proposed measures of improvement to reduce de incidence of suicide in adolescents.

Strategic lines of the 2022–2026 Mental Health Action Plan.

| Line 5: Child and adolescent mental health |

|---|

| Objectives: |

| 1. Promotion of child and adolescent mental health. Prevention and early detection of mental health problems in these age groups |

| 2. Provision of care to children and adolescents with mental health problems |

| 3. Fight against the social discrimination and stigmatization of children and adolescents with mental health problems |

| Priority actions and lines of action: |

| 1. Reinforcement of human resources |

| 2. Comprehensive mental health care |

| 3. Actions against stigmatization |

| 4. Prevention, detection and management of suicidal behaviour |

| 5. Approach in contexts of increased vulnerability |

| 6. Prevention of addictive behaviours |

| Line 3: Prevention, early detection and management of suicidal behaviour |

|---|

| 1. Early detection and prevention of suicidal behaviours |

| 2. Creating awareness and sensitivity and improving knowledge of the general population through awareness, sensitivity and information campaigns promoted through public institutions, mass media and social entities devoted to suicide prevention |

| 3. Promote the development of integrated care pathways for individuals at risk of suicide: |

| a. Improve the care of individuals at risk of suicide |

| b. Support and promote peer support measures in survivors of suicide attempts and individuals with suicidal ideation |

| c. Support and promote community-based peer support measures for families with individuals grieving on account of a suicide |

| d. Provide guidance and support to professionals who have experienced a suicide in the workplace |

| e. Facilitate and promote direct access to adolescents with mental health problems through specific mental health programmes for those who exhibit suicidal ideation |

| f. Develop an efficient, coordinated and integrated telephone helpline network to improve the management of individuals at risk of suicide |

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends starting universal screening for suicide risk at age 12 years to identify adolescents at risk of depression and/or suicidal ideation and deliver early intervention. Other groups have analysed the outcomes of the selective or universal application of a scale to screen for suicide risk in paediatric emergency departments.25–27 In Spain, the use of measurement instruments tested and validated for assessment of suicidal behaviour in adolescents is scarce. Recently, some ACs, such as the Basque Country, have proposed the application of a questionnaire for detection of depression symptoms at age 13–14 years in the routine checkups scheduled through the primary care Healthy Child Programme.

Table 5 presents the most important recommendations proposed by the Multidisciplinary Working Group on Paediatric Mental Health, with an emphasis on the need of a multidisciplinary approach.

Recommendations of the Multidisciplinary Working Group on Paediatric Mental Health of the AEP.

| 1. Creation of a national suicide prevention plan. Standardise suicide prevention programmes across autonomous communities |

| 2. Improve and increase material and human resources for child and adolescent mental health services at the inpatient and outpatient levels |

| 3. Implement training programmes in schools for teachers, counsellors and other staff involved in delivering services to children (role of student wellbeing and protection coordinator) |

| 4. Specific training on child and adolescent psychiatry for paediatricians, especially those in the fields of primary care and emergency medicine. Include rotations in the paediatrics MIR training |

| 5. Integrate early detection screening for suicide prevention in primary care, in- or out-of-hospital emergency care and inpatient care settings |

MIR: medical intern/resident.

Suicidal behaviours, self-injury and completed suicides are increasing at an alarming rate in children and adolescents in our area, especially since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. Non-suicidal self-injuries are very frequent and may be associated with suicidal ideation in the same individual. It is essential that we learn to differentiate and assess them, with particular emphasis on the warning signs. The factors involved in suicidal behaviour are multiple and diverse, and professionals in contact with children and adolescents must be aware of all of those that are preventable. Paediatricians, especially those in primary care, need to know how to handle consultations related to suicide, starting with developing the necessary skills to carry out a full interview with a supportive and empathetic attitude. At present, prevention plans at the autonomous community levels are heterogeneous or, in some cases, missing, so the creation of a national suicide prevention plan is essential. There is a pressing need to reinforce the resources of primary care, hospital-based and mental health services providing care to the paediatric population. Schools are key in the prevention and detection of suicidal behaviours, and training programmes must be established for education professionals. Training in child and adolescent psychiatry for paediatricians, primary care physicians and nurses through visiting rounds, continuing education, remote consultation and coordination meetings should be offered, possibly including a mandatory rotation in psychiatry in the paediatrics residency curriculum.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the Asociación Española de Pediatría for the support provided to develop this project. Also, the patients and families that closely experience suicide or suicidal behaviour, for the trust they have placed on us, the professionals that aim to help them. We also thank the Working Group on Poisoning of the SEUP.