The use of certain Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM) in children has been documented in Spain. The main aim of this study is to estimate the knowledge, recommendations, and use of CAM by Spanish paediatricians.

Material and methodsA national study was conducted from June to July 2020 using an online questionnaire. Two e-mails were sent to paediatricians who were members of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics (AEP).

ResultsOut of 1414 responses received, acupuncture was considered as a science by 31.8%. Homeopathy was recommended to parents by 28.1%. CAM was used by 21.3% of physicians, at least once, to improve their own health. Only 3.8% had ever replaced a conventional treatment with CAM. The following variables were associated with a greater disposition to prescribe homeopathy: female, age over 45 years old, paediatricians working in Primary Care, and paediatricians working in private healthcare.

ConclusionsThis AEP Committee on Medicines questionnaire provides new data that should be considered alarming and should ask for a serious thinking on the use of CAM in Spain. Some paediatricians are recommending parents to give treatments not supported by scientific evidence to their children. This practice could be potentially harmful, especially when conventional treatment is being replaced.

El uso de determinadas pseudociencias en niños está documentado en España. El objetivo principal del estudio es estimar el grado de conocimiento, la recomendación y el uso de algunas pseudoterapias por parte de los pediatras españoles.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo y de ámbito nacional, mediante encuesta en línea, enviada por correo electrónico a pediatras socios de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP), entre junio y julio de 2020.

ResultadosSe recibieron 1.414 respuestas. El 31,8% considera que la acupuntura es una ciencia. El 28,1% ha recomendado alguna vez homeopatía a sus pacientes. Un 21,3% reconoce haber utilizado alguna medicina alternativa para mejorar su propia salud. El 3,8% reconoce haber sustituido un tratamiento convencional por una terapia alternativa. Las variables que se asociaron a una mayor predisposición para recomendar homeopatía fueron: sexo femenino, edad > 45 años, trabajo en atención primaria y en un sistema de salud privado.

ConclusionesEl Comité de Medicamentos de la AEP aporta con esta encuesta nuevos datos que se consideran preocupantes y que merecen una seria reflexión sobre el uso de las pseudociencias en nuestro país. Un significativo porcentaje de pediatras están recomendando a los padres que administren a sus hijos tratamientos no avalados por la evidencia científica, con todas las consecuencias negativas y perjuicios que esto puede conllevar, sobre todo si se sustituye el tratamiento convencional.

At present, numerous therapies that are not based on current scientific evidence are offered to cure diseases, improve symptoms or promote health.1 The terminology used is heterogeneous and confusing, including names as “alternative medicine”, “naturopathy”, “complementary medicine” or “pseudoscience”.1 The Spanish government, through the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, has analysed 138 techniques used for therapeutic or health promotion purposes.2 Of these techniques, 72 have already been classified as pseudotherapies and another 66 are still being investigated.3 On the other hand, the Board of Physicians of Spain maintains an observatory for the surveillance of pseudosciences, pseudotherapies, practices that encroach on the medical scope of practice and medical sects, and has proposed a classification of what is known as natural therapies.4

There is ample evidence of the extensive use of these modalities by part of the population,5–12 including children,5–9 and in Spain.5,6 A recent study also highlighted the fact that it is sometimes health care professionals who frequently recommend treatments whose efficacy has not been proven, that are not free of risk and that result in unnecessary costs.5 In light of the situation, and since, to our knowledge, no nationwide survey has been conducted to assess the use and knowledge of pseudosciences by paediatricians in Spain, the Committee on Medicines (CM) of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Paediatrics), with the help of the AEP in distributing the questionnaire, carried out a pioneering study with the primary objective of estimating the degree of knowledge, the recommendation and the use of certain pseudotherapies by Spanish paediatricians. The secondary objective was to analyse whether sex, age, care setting (primary or specialty care) or health care system based on source of funding (public vs private health care system) were associated significantly with the answers.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive study of nationwide scope. We collected data through an online questionnaire completed on an anonymous and voluntary basis and consisting of multiple-choice questions (Appendix B), distributed to paediatricians members of the AEP through electronic mail. The questionnaire was developed using Google Drive®.

We collected responses from June 15 to July 15, 2020. The inclusion criteria were having a degree in medicine, working as a paediatrician or a resident in paediatrics and membership in the AEP.

As of June 15, 2020, the AEP had a total of 11 454 members. Sixty-five percent were female. The age was documented in 7375 members, with the largest proportion corresponding to the group aged more than 55 years (32.2%), followed by the group under 35 years (24.9%), the 36-to- 45 years group (23.6%), and the 46-to-55 years group (19.3%).

We had access to the e-mail addresses of all members and emailed the questionnaire on 2 dates: June 15 and July 1. The email was opened by 10 791 members. We estimated that we would receive responses from 1355 paediatricians, a sample size that would suffice to assess the knowledge and use of alternative medicine practices by paediatricians members of the AEP, with a maximum error of 2.5%, an estimated proportion of 50% and a 95% level of confidence.

We collected data on the following: sex, age, care setting where respondent worked most of the time (primary care/specialty care), health care system where respondent worked habitually (public vs private), and answers to the survey questions. We selected 10 techniques used for health-related purposes: homeopathy, reiki or healing touch, magnet therapy, acupuncture, Bach flower remedies, orthomolecular medicine, iridology, bioneuroemotion, colon cleansing and crystal healing.

In the descriptive analysis, we expressed qualitative variables as relative frequencies. We did not obtain quantitative data, as we grouped temporal variables in intervals. We analysed variance by means of the χ2 test or Fisher exact test in the case of expected cell counts of less than 5. In the multivariate analysis, we used unconditional logistic regression analysis, in which the initial dependent variable was the recommendation of use of certain therapies in children, and the independent variables included in the full model were sex, age, care setting and health care system (private vs public). The reference groups were male sex, age equal or greater than 45 years, primary care and public health system, respectively. We have expressed the results as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with the corresponding confidence intervals (CIs). We considered results with p-values of less than 0.05 statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with the software IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.

Since we did not include personally identifiable data and questionnaires were completed anonymously and on a voluntary basis, we considered the survey exempt from the need of approval by an ethics committee. Access to survey data was limited to the researchers involved in the study, and the data was collected solely for statistical purposes.

ResultsWe received 1414 responses. The distribution of responses by age and sex was representative of the membership of the AEP: 68% of respondents were female; most paediatricians were aged more than 55 years, followed in frequency by the 36−45 years group (21.9%), under 35 years group (21.5%) and 46−55 years group (20.9%). Of the total sample, 51.8% worked in primary care and 87.8% in the public health system.

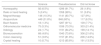

Table 1 presents the results regarding the categorization of the different therapies under study as sciences versus pseudosciences. We ought to highlight that 31.8% of surveyed paediatricians considered acupuncture a science. Table 2 summarises the answers to the question of whether respondents had ever recommended any of these therapies to a patient. Although only 6.5% of paediatricians considered homeopathy a science, 28.1% reported having recommended it in the past, and this was the most frequently prescribed modality, followed by acupuncture (19.2%), Bach flowers (4.5%) and magnet therapy (4.3%).

Categorization by paediatricians of the different techniques under study as sciences or pseudosciences, n = 1414.

| Science | Pseudoscience | Did not know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homeopathy | 92 (6.5%) | 1296 (91.7%) | 26 (1.8%) |

| Reiki or hand healing | 5 (0.4%) | 1358 (96%) | 51 (3.6%) |

| Magnet therapy | 146 (10.3%) | 1141 (80.7%) | 127 (9%) |

| Acupuncture | 449 (31.8%) | 848 (60%) | 117 (8.3%) |

| Bach flowers | 18 (1.3%) | 1287 (91%) | 109 (7.7%) |

| Orthomolecular medicine | 75 (5.3%) | 1036 (73.3%) | 303 (21.4%) |

| Iridology | 24 (1.7%) | 1191 (84.2%) | 199 (14.1%) |

| Bioneuroemotion | 68 (4.8%) | 1040 (73.6%) | 306 (21.6%) |

| Colon cleansing | 51 (3.6%) | 1157 (81.8%) | 206 (14.6%) |

| Crystal healing | 10 (0.7%) | 1213 (85.8%) | 191 (13.5%) |

Respondents that had ever recommended at least one of the techniques under study in their professional practice, n = 1414.

| Ever | Never | |

|---|---|---|

| Homeopathy | 397 (28.1%) | 1017 (71.9%) |

| Reiki or hand healing | 47 (3.3%) | 1367 (96.7%) |

| Magnet therapy | 61 (4.3%) | 1353 (95.7%) |

| Acupuncture | 272 (19.2%) | 1142 (80.8%) |

| Bach flowers | 64 (4.5%) | 1350 (95.5%) |

| Orthomolecular medicine | 33 (2.3%) | 1381 (97.7%) |

| Iridology | 23 (1.6%) | 1391 (98.4%) |

| Bioneuroemotion | 33 (2.3%) | 1381 (97.7%) |

| Colon cleansing | 31 (2.2%) | 1383 (97.8%) |

| Crystal healing | 21 (1.5%) | 1393 (98.5%) |

The χ2 test applied to the contingency tables composed with the results presented in Table 2 for comparison with sex, age, care setting and health care system found statistically significant differences in some instances. For example, prescription of homeopathy was more frequent among female clinicians, clinicians older than 45 years, primary care providers and providers in the private health system. Prescription of reiki, Bach flowers and bioneuroemotion was also more frequent among female respondents. Paediatricians aged more than 45 years were more likely to recommend acupuncture and Bach flowers. Bach flowers were also used more frequently in the primary care setting. The prescription of orthomolecular medicine and bioneuroemotion techniques was more frequent in the private health system. Table 3 presents a summary of these results.

Association between the variables under study and the recommendation of pseudosciences by paediatricians that acknowledged having prescribed them to their patients (univariate analysis). Results with p-values of less than 0.05 are presented in boldface.

| Sex | Age | Care setting | Health system | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Male (n = 453) | Female (n = 961) | P | < 35 (n = 304) | 36−45 (n = 310) | 46−55 (n = 295) | > 55 (n = 505) | P | AP (n = 732) | AE (n = 682) | P | Public (n = 1241) | Private (n = 173) | P | |

| Homeopathy | 397 (28.1%) | 105 (23.2%) | 292 (30.4%) | .005 | 40 (13.2%) | 84 (27.1%) | 122 (41.4%) | 151 (29.9%) | < .001 | 284 (38.8%) | 113 (16.6%) | < .001 | 73 (5.9%) | 19 (11.0%) | .019 |

| Reiki or hand healing | 47 (3.3%) | 6 (1.3%) | 41 (4.3%) | .004 | 14 (4.6%) | 8 (2.6%) | 9 (3.1%) | 16 (3.2%) | .533 | 25 (3.4%) | 22 (3.2%) | .843 | 5 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | .188 |

| Magnet therapy | 61 (4.3%) | 15 (3.3%) | 46 (4.8%) | .203 | 15 (4.9%) | 9 (2.9%) | 12 (4.1%) | 25 (5.0%) | .509 | 35 (4.8%) | 26 (3.8%) | .370 | 120 (9.7%) | 26 (15.0%) | .061 |

| Acupuncture | 272 (19.2%) | 96 (21.2%) | 176 (18.3%) | .200 | 46 (15.1%) | 52 (16.8%) | 46 (15.6%) | 128 (25.3%) | < .001 | 133 (18.2%) | 139 (20.4%) | .292 | 395 (31.8%) | 54 (31.2%) | .900 |

| Bach flowers | 64 (4.5%) | 6 (1.3%) | 58 (6.0%) | <.001 | 12 (3.9%) | 6 (1.9%) | 23 (7.8%) | 23 (4.6%) | .006 | 46 (6.3%) | 18 (2.6%) | .001 | 14 (1.1%) | 4 (2.3%) | .416 |

| Orthomolecular medicine | 33 (2.3%) | 6 (1.3%) | 27 (2.8%) | .084 | 9 (3.0%) | 6 (1.9%) | 5 (1.7%) | 13 (2.6%) | .706 | 21 (2.9%) | 12 (1.8%) | .167 | 59 (4.8%) | 16 (9.2%) | .037 |

| Iridology | 23 (1.6%) | 4 (0.9%) | 19 (2.0%) | .094 | 8 (2.6%) | 4 (1.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 8 (1.6%) | .419 | 14 (1.9%) | 9 (1.3%) | .378 | 22 (1.8%) | 2 (1.2%) | .835 |

| Bioneuroemotion | 33 (2.3%) | 4 (0.9%) | 29 (3.0%) | .007 | 9 (3.0%) | 8 (2.6%) | 9 (3.1%) | 7 (1.4%) | .353 | 19 (2.6%) | 14 (2.1%) | .499 | 53 (4.3%) | 15 (8.7%) | .020 |

| Colon cleansing | 31 (2.2%) | 5 (1.1%) | 26 (2.7%) | .055 | 14 (4.6%) | 6 (1.9%) | 3 (1.0%) | 8 (1.6%) | .011 | 16 (2.2%) | 15 (2.2%) | .986 | 44 (3.5%) | 7 (4.0%) | .755 |

| Crystal healing | 21 (1.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 18 (1.9%) | .058 | 8 (2.6%) | 4 (1.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 6 (1.2%) | .313 | 12 (1.6%) | 9 (1.3%) | .619 | 9 (0.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | .807 |

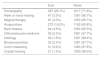

Overall, 3.8% of paediatricians in the sample reported ever replacing conventional medicine by any of the therapies under study. We did not find significant differences based on the variables under study. However, up to 21.3% of respondents acknowledged having used these therapies to improve their own health, a practice that was also more frequent in female clinicians, clinicians over 45 years and primary care paediatricians. Table 4 summarises these results. Of the 301 paediatricians that acknowledged having used these therapies, 73.7% reported having tried homeopathy, 53.5% acupuncture, 9.6% Bach flowers and 7.6% other approaches. Although this was not asked explicitly in the questionnaire, in the open text field 18.6% reported that they did not experience any improvement with the alternative therapy, compared to 1.6% that reported healing with such treatment. In addition, 13.9% of paediatricians did not specify which approach they had tried, while 40.2% reported having tried 2 or more of these treatments.

Association between the variables under study, the acknowledgment of having replaced conventional treatment by a pseudoscience and the use of pseudotherapies by paediatricians for their own health (univariate analysis). Results with p-values of less than 0.05 are presented in boldface.

| Sex | Age | Care setting | Health system | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Male (n = 453) | Female (n = 961) | P | < 35 (n = 304) | 36−45 (n = 310) | 46−55 (n = 295) | > 55 (n = 505) | P | AP (n = 732) | AE (n = 682) | P | Public (n = 1241) | Private (n = 173) | P | |

| I have used them instead of conventional treatment in the past | 48 (3.4%) | 14 (3.1%) | 34 (3.5%) | .665 | 6 (2.0%) | 10 (3.2%) | 11 (3.7%) | 21 (4.2%) | .408 | 30 (4.1%) | 18 (2.6%) | .130 | 41 (3.3%) | 7 (4.0%) | .613 |

| I have used them to improve my own health | 301 (21.3%) | 62 (13.7%) | 239 (24.9%) | < .001 | 60 (19.7%) | 75 (24.2%) | 76 (25.8%) | 90 (17.8%) | .027 | 172 (23.5%) | 129 (18.9%) | .035 | 261 (21%) | 40 (23.1%) | .529 |

Of the paediatricians that had recommended an alternative therapy to their patients, 51.5% had also used them to improve their own health.

In the last item in the questionnaire, 39.4% of paediatricians declared that they did not consider pseudotherapies beneficial or harmful for health, while 36.3% considered them deleterious, 16.7% declared they did not know and 7.6% considered them beneficial. The differences based on sex remained, as a higher proportion of men than women considered these therapies potentially harmful. These results are presented in Table 5.

Association between the variables under study and the perception of the potential beneficial or deleterious effect of the use of pseudosciences to supplement conventional treatment (univariate analysis). Results with p-values of less than 0.05 are presented in boldface.

| Sex | Age | Care setting | Health system | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Male (n = 453) | Female (n = 961) | P | < 35 (n = 304) | 36-45 (n = 310) | 46−55 (n = 295) | > 55 (n = 505) | P | AP (n = 732) | AE (n = 682) | P | Public (n = 1241) | Private (n = 173) | P | |

| It is beneficial for health | 108 (7.6%) | 21 (4.6%) | 87 (9.1%) | .009 | 24 (7.9%) | 22 (7.1%) | 27 (9.2%) | 35 (7.1%) | .362 | 64 (8.7%) | 44 (6.5%) | .112 | 96 (7.7%) | 12 (6.9%) | .470 |

| It is deleterious to health | 513 (36.3%) | 199 (43.9%) | 314 (32.7%) | < .001 | 89 (29.3%) | 107 (34.5%) | 111 (37.6%) | 206 (40.8%) | .008 | 277 (37.8%) | 236 (34.6%) | .197 | 455 (36.7%) | 58 (33.5%) | .142 |

| It is neither beneficial nor deleterious for health | 557 (39.4%) | 173 (38.2%) | 384 (40.0%) | .653 | 152 (50.0%) | 114 (36.8%) | 114 (38.6%) | 177 (35.0%) | .024 | 262 (35.8%) | 295 (43.3%) | .038 | 480 (38.7%) | 77 (44.5%) | .042 |

| I don’t know | 236 (16.7%) | 60 (13.2%) | 176 (18.3%) | .064 | 39 (12.8%) | 67 (21.6%) | 43 (14.6%) | 87 (17.2%) | .065 | 129 (17.6%) | 107 (15.7%) | .292 | 210 (16.9%) | 26 (15.0%) | .806 |

We performed a multivariate analysis on the techniques recommended most often by paediatricians in Spain: homeopathy and acupuncture. Table 6 presents the results. When it came to homeopathy, the factors that weighed most on its recommendation were, once again, female sex and practice within the private health system, while the specialty care setting and age under 45 years were associated with less frequent prescription of homeopathy. This was not the case of acupuncture, with the exception of age, as it was also recommended less frequently by respondents aged less than de 45 years.

Recommendation of the use of homeopathy and acupuncture by sex, age, care setting and health system.

| Homeopathy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By sex | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Female | 961 | 30.4% | 1747 | 1305−2399 |

| Male | 453 | 23.2% | Ref | |

| By age | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Age ≤ 45 years | 614 | 20.2% | 0.616 | 0.469−0.810 |

| Age > 45 years | 800 | 34.1% | Ref | |

| By care setting | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Specialty care | 682 | 16.6% | 0.353 | 0.270−0.462 |

| Primary care | 732 | 38.8% | Ref | |

| By health system | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Private | 173 | 11.0% | 3006 | 2110−4283 |

| Public | 1241 | 5.9% | Ref | |

| Acupuncture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Male | 961 | 21.2% | 0.951 | 0.707−1278 |

| By age | 453 | 18.3% | Ref | |

| Age ≤ 45 years | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Age > 45 years | 614 | 16.0% | 0.639 | 0.474−0.860 |

| By care setting | 800 | 21.7% | Ref | |

| Specialty care | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Primary care | 682 | 20.4% | 1290 | 0.974−1710 |

| By health system | 732 | 18.2% | Ref | |

| Private | n | Has recommended before | aOR | 95% CI |

| Public | 173 | 31.2% | 0.916 | 0.607−1382 |

| Female | 1241 | 31.8% | Ref | |

Multivariate analysis: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference group.

Our survey collected data from 1500 paediatricians in Spain regarding their knowledge, recommendation and use of certain pseudotherapies. One out of 4 reported having recommended homeopathy to some of their patients, but only 1 out of 15 considered it a science. Nearly a third considered acupuncture a science, and 1 in 5 had recommended it in the past. Ten percent considered magnet therapy a science. It is also worth mentioning that 1 out of 5 responded they did not know whether bioneuroemotion or orthomolecular medicine should be classified as a science or a pseudoscience.

The findings of the survey are alarming and call for a serious reflection on the situation of pseudosciences in Spain. The issue is not just whether they are being used by the population. As Arévalo-Cenzual et al. already noted,5 the proportion of paediatricians that deviate from evidence-based practice to recommend therapies of unproven efficacy is not negligible. In addition, 1 in 5 paediatricians acknowledged having used some of these modalities to improve their own health. Only 3.4% of respondents reported having replaced conventional treatment by an alternative therapy in the past. This is an encouraging datum, although it still means that approximately 500 paediatricians in Spain may be engaging in potentially chargeable practices that may be harmful to health, depending on the active ingredient that is replaced or substituted. Needless to say, it is not the same to omit cold medication than chemotherapy. In this survey, we did not examine the type of treatment that was being replaced, so we do not know the extent of the harm that could have been done.

Nevertheless, we must interpret these data critically. There are limitations and possible biases in the study, including those intrinsic to voluntary surveys. For instance, the therapeutic recommendations of paediatricians that did not respond could differ from those that did. This could be a source of selection bias associated with our recruitment method, as the willingness to respond to an online survey may be related to a specific profile of paediatrician. We did not study the profile of respondents versus nonrespondents. Although we obtained a sufficient number of responses and the potential sampling error was low, this study only represents the beliefs and practices of 12% of paediatricians members of the AEP. It is also based on the assumption that responses were true, and it is possible that there was incongruence between what respondents reported and what they actually do or recommend.

Despite these limitations, the association of both the use and the recommendation of “alternative medicine” to female sex, older age and previous use of these therapies by the clinician for their personal health had already been described in similar studies.6,11–14 Greater use of these therapies has also been described in individuals with higher socioeconomic status and/or educational attainment,6,11 aspects that we did not assess in the survey. On the other hand, the more frequent recommendation at the primary care level and in the private health care system had not been reported in previous works. If they are confirmed in future studies, these newly identified factors should also be taken into account.

The lack of knowledge regarding “alternative medicine” by some clinicians had also been described in the past.7,13–15 The authors of some of these studies, published in scientific journals that advocate for this type of therapies, consider that physicians need to be better informed about the different techniques that may be used with the intent to heal or promote health, in order to understand how they work, be familiar with their use and be able to offer them to their patients. The CM-AEP does not agree with this recommendation, as numerous studies have provided evidence that the use of pseudosciences is potentially harmful.5,6,10,15,16

Along these lines, López Sanguos et al.15 described the case of an infant aged 21 months that required hospitalization for 24 h and delivery of activated charcoal through a feeding tube following the administration by the parents of a homeopathic product that included belladonna among its ingredients. The authors concluded that the lack of knowledge on homeopathic products by health care providers and of clear information in the patient information leaflet provided with the products are the main reason for the development of serious adverse event. When it comes to belladonna, its content in certain homeopathic tablets has motivated a specific alert from the Food and Drug Administration, published in April 2019, after evidence emerged that the amount of some potentially harmful active principles was not uniform in the tablets available in the market.17

We also ought to highlight the pharmacological surveillance bulletin data on the safety of homeopathic products, published by the regional government of Andalusia in 2012.18 The report documented 77 notifications of adverse events associated with homeopathy including minute amounts of active principles that could trigger hypersensitivity reactions, potential contamination of sampled products with pesticides or heavy metals, use of mother tincture in its most concentrated form or confusion of dilution measures.

The CM-AEP considers the establishment of specific regulations on the application of the different techniques used for health care purposes necessary and urgent to guarantee, at the very least, the safety of these treatments.5 To prevent this type of serious adverse events, the most important thing may be to specifically regulate homeopathy in Spain, as opposed to increasing the training of health care professionals on therapies of unproven efficacy. This is not to say that paediatricians do not need ample and rigorous information on the scientific evidence available on these treatment modalities and their potential side effects. A basic understanding of the basic principles of the most widely used therapies is also important to be able to discuss with parents and patients how the use of therapies based on false or misleading scientific claims is not ideal. This training could start as early as medical school. The CM-AEP also considers that it should be mandatory to provide evidence of the efficacy of products for the indications given for their use if they are authorised for commercial distribution.

Lastly, some authors have found an association between the use of “natural medicine” and vaccine hesitancy,19 or the reluctance of parents to have their children vaccinated. For example, Bleser et al.8 described a higher proportion of children not vaccinated against influenza in the United State in the subset that had ever been treated with alternative therapies compared to the subset that had never received those treatments. In a similar study conducted in Washington, Downey et al.9 concluded that children that had been treated with some form of natural therapy not only exhibited poorer adherence to official immunization schedules, but also had a higher risk of diagnosis of all vaccine-preventable diseases. We chose not to ask paediatricians about this aspect in our survey, as it fell outside the scope of the study objectives. However, we would advise exploring the vaccination status of any child that is receiving any form of pseudotherapy.

In conclusion, the CM-AEP, as an independent group of paediatricians expert in medication, maintains its stance in relation to the use of alternative medicine approaches and pseudosciences in children1 and considers that no health care provider should ever recommend treatments that are not supported by scientific evidence. With this survey, the CM-AEP contributes new data that are alarming and call for a serious reflection on the use of pseudosciences in Spain, as a significant proportion of paediatricians are advising parents to give their children treatments that are not based on scientific evidence, with all the potential deleterious effects and harm that this could entail, especially if these modalities are used instead of conventional medical treatment. It is clear that there is ample opportunity for improvement, but this will not occur without the support and help of scientific societies, professional boards, universities and the government itself.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The Committee on Medicines of the AEP thanks every paediatrician for their generosity in participating and for devoting part of their valuable time in responding to the survey on the use and knowledge of pseudosciences. We also want to specifically thank Dr Carlos Ochoa Sangrador, a paediatrician at the Hospital Virgen de la Concha (Zamora), for his disinterested review of the manuscript, and lastly, Iván Rodríguez Fernández, member of the office management department of the AEP, for his invaluable help in the dissemination of the questionnaire, without which this study would not have been possible.

Please cite this article as: Piñeiro Pérez R, Núñez Cuadros E, Cabrera García L, Díez López I, Escrig Fernández R, Gil Lemus MA, et al. Resultados de una encuesta nacional sobre conocimiento y uso de pseudociencias por parte de los pediatras. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:25–34.