Adolescence is a decisive stage in human development in which intense physical, psychological, emotional and social changes are experienced. There are many influential factors in health, highlighting among them the environment.

ObjectiveThe objective of the study was to analyse the lifestyle differences associated with the health of adolescents as a function of rural and urban environment.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted with a sample of 761 students (14.51 ± 1.63 years) from 25 educational centers in a region of northern Spain, distributed between 650 urban and 111 rural students. Life habits and different indicators of physical, psychological and social health were evaluated, assessing the level of physical activity, maximum oxygen consumption, hours of night sleep, quality of life related to health, self-esteem, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the environment and the socioeconomic level.

ResultsAdolescents in rural areas reported a greater number of hours of night sleep and higher levels of HRQL, both as a whole, and specifically in psychological well-being, school environment and autonomy and parents. Adolescents in urban areas reported higher levels of physical activity between 6:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m., and a higher consumption of fast food.

ConclusionsThe results show the need for strategies aimed at counteracting the negative influence that physical and sociodemographic factors typical of urbanized areas exert on HRQL. On the other hand, in relation to lifestyle habits, a wider range of extracurricular physical activities in rural areas would be recommended.

La adolescencia es una etapa decisiva en el desarrollo humano en la que se experimentan intensos cambios físicos, psicológicos, emocionales y sociales. Existen multitud de factores influyentes en la salud, destacando entre ellos el entorno.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del estudio fue analizar las diferencias en el estilo de vida y diversos indicadores de salud psicológica, física y social de los adolescentes en función del entorno rural y urbano.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio trasversal en una muestra de 761 estudiantes (14,51 ± 1,63 años) de 25 centros educativos de una región del norte de España, distribuidos en 650 alumnos urbanos y 111 rurales. Se evaluaron los hábitos de vida y diferentes indicadores de salud física, psicológica y social, valorando el nivel de actividad física, el consumo máximo de oxígeno, las horas de sueño nocturno, la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS), la autoestima, la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea, el entorno ambiental y el nivel socioeconómico.

ResultadosLos adolescentes de zonas rurales reportaron un mayor número de horas de sueño nocturno y mayores niveles de CVRS, tanto en su conjunto, como de forma específica en el bienestar psicológico, entorno escolar y autonomía y padres. Los adolescentes de zonas urbanas mostraron mayores niveles de actividad física entre las 18:00 a 22:00, y un mayor consumo de comida rápida.

ConclusionesLos resultados manifiestan la necesidad de estrategias dirigidas a contrarrestar la influencia negativa que los factores físicos y sociodemográficos propios de las zonas urbanizadas ejercen en la CVRS. Por otro lado, en relación con los hábitos de vida, sería recomendable una oferta más amplia de actividades físicas extraescolares en las zonas rurales.

Adolescence is considered a key stage in personality development and in the consolidation of lifestyle habits, during which emerging changes at the psychological, biological, physical and social levels increase the risk of acquiring habits deleterious to health.1 Therefore, supporting the development of healthy habits is key to the prevention of health problems.2 In this context, the stage of adolescence has attracted considerable interest, with multiple studies devoted to the investigation of the most influential factors. Thus, multiple aspects, such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle habits and genetic, environmental, social and psychological factors are known determinants of health.3,4 Given this, for each of these determinants, it would be interesting to compare health status and habits in adolescents living in rural versus urban areas, since there is little evidence on the subject.

The concepts of rural setting and urban setting have been defined from different perspectives, taking into account quantitative criteria (population ranges), qualitative criteria (population density or type of economic activity) or subjective criteria (perception of inhabitants or their residential setting).5 Based on Eurostat data for 2019,6 63.32% of the population of Spain resides in predominantly urban areas, 33.31% in intermediate areas and 3.37% in rural areas, revealing substantial heterogeneity in residential settings. In relation to this, the differences between rural and urban environments in the access to sports facilities, fast food restaurants, transportation systems and living conditions can have a direct impact on the adherence to certain lifestyles, which in turn can have a direct impact on physical activity (PA) and adherence to a healthy diet.7,8 When it comes to quality of life, it seems to be influenced by physical factors such as pollution, the environment, decreased access to nature, public spaces and population density, as well as social factors such as the fast pace of life, stress and social isolation, all of which are more likely to affect residents of urban areas.9–11

A majority of studies on the differences between rural and urban areas have performed partial analyses of health determinants, with few studies taking a comprehensive approach to this issue. Thus, the objective of our study was to analyse the differences between adolescents residing in rural and urban areas in a region in northern Spain from a comprehensive health perspective. To this end, we assessed lifestyle habits and different indicators of physical, psychological and social health, the level of PA, the maximal oxygen update, night-time sleep duration, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), self-esteem, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, environmental variables and socioeconomic status (SES).

Material and methodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted a cross-sectional study in a sample of students enrolled in years 1 and 4 of compulsory secondary education (“educación secundaria obligatoria”, ESO) in schools in the region of La Rioja in northern Spain. We used single-stage cluster sampling in which the units were all the classes of the selected years. Given the study universe (3470 students in year 1 of the ESO and 2548 in year 4 of the ESO), we calculated the sample size required to obtain a representative sample for each school year with a 95% level of confidence and a precision of 5%, for an expected proportion of 0.50. With these parameters, we estimated that the sample would be representative by including at least 346 students in year 1 and 334 students in year 4. Since each class had a mean of 25 students in both years, and having increased the required sample size according to the expected participation rate of 60%, we randomly selected 23 year 1 classes and 22 year 4 classes to obtain a representative sample.

We invited every student in each selected class to participate in the study, and 82% agreed to participate, the final sample included 761 adolescents in 45 classes in 25 schools, 383 in year 1 and 378 in year 4. The age of participants ranged from 12 to 17 years (mean, 14.51; standard deviation [SD], ±1.63), 49.7% were female and 50.3% male. We classified residential setting (urban vs rural) based on the number of inhabitants, considering townships with fewer than 5000 inhabitants rural.12 Based on this definition, 85.4% of participants resided in urban areas and 14.6% in rural areas.

ProcedureWe obtained written informed consent from the parents or legal guardians of participants. Adolescents participated in the study on a voluntary basis after providing verbal assent. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Rioja. The research team conducted the fieldwork during regular school hours and applying a standardised study protocol in every class: self-administered questionnaire, anthropometric measurements and fitness test. The data collection period ranged from January to June 2018.

InstrumentsWe measured HRQoL with the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire version validated in the adolescent population of Spain.13 It comprises 27 items rated on a Likert scale and grouped in 5 dimensions: physical well-being, psychological well-being, autonomy & parents, school environment and peers & social support. We interpreted the data as directed by the developers of the test, with higher scores indicative of more positive perceptions of HRQoL.

We assessed self-esteem with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale, also validated in Spanish adolescents.14 It comprises 10 items with answers rated 1–4 and yields a total score ranging from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicative of greater self-esteem.

We assessed the level of PA by means of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) adapted and validated for the adolescent population of Spain.15 This instrument assesses PA in the past 7 days with items scored on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of PA. We also added 2 items to assess participation in organised extracurricular sports and whether participants engaged in physical activity on their way to and from school (“Do you practice any extracurricular sports after school?” and “Are you physically active on your way to school? (go to school walking, on a bicycle, on skates…?”). To calculate the total hours of night-time sleep, we asked adolescents which time they went to bed and which time they woke up.

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was assessed by means of the KIDMED questionnaire.16 It comprises 16 items that assess Mediterranean diet patterns with a dichotomous yes/no answer. The possible score ranges from –4 to 12, and higher scores reflect greater adherence to Mediterranean diet.

We evaluated environmental factors related to PA through the Assessing Levels of PHysical Activity and fitness at population level (ALPHA) environmental questionnaire, validated for use in Spanish youth.17 This questionnaire assesses the perception of factors in the immediate environment (within an approximate 1.5 km radius from the home) that may affect performance of PA, such as: type and location of the home, access to facilities and materials to engage in PA in the home and immediate environment, proximity of services, traffic and neighbourhood safety. The total score is obtained from adding up the scores in the 10 items, and higher scores represent an environment that is more conducive to performance of PA.

Socioeconomic status was assessed with the Family Affluence Scale III,18 which comprises 6 items relating to the material resources and property of the family. The score ranges from 0 and 13, with 13 corresponding to the highest level of wealth.

In addition, we used the Oviedo infrequency scale (INF-OV)19 to identify and exclude from the analysis those questionnaires that had been completed randomly, with non-random patterned responding or dishonestly. It is a self-report instrument consisting of questions with obvious answers given in a dichotomous format (0 = yes; 1 = no). We inserted 6 INF-OV items alternating with regular questionnaire items. We excluded participants with more than 1 illogical answer to these items, which turned out to be 2 of the total.

We measured height with a Holtain® stadiometer (Holtain Ltd., Dyfed, United Kingdom) accurate to 1 mm and body weight with a SECA® scale (model 713; Hamburg, Germany) accurate to 0.1 kg. We subsequently calculated the BMI and classified it according to the World Health Organization growth reference data (normal weight, overweight and obesity).20

To assess aerobic capacity, we used the Course-Navette test. We drew two transversal lines at a distance of 20 m marking the beginning and end of the path for a run. Participants had to run between both lines at a pace determined by a sequence of beeps. The beeps set a pace of 8.5 km/h at the beginning of the run and increased it by 0.5 km/h each minute. For each participant, the test ended when the participant stopped or could not complete the path at the established pace 2 consecutive times. We used the resulting data to calculate the maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) using the formula developed by the author of the test.21

Statistical analysisWe have summarised quantitative data as mean and standard deviation, and qualitative data as frequency distributions. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess the normality of the distribution and the Levene test to assess the homogeneity of variance. We compared quantitative data with the Student t test in case of a normal distribution and otherwise with the Mann-Whitney U test. We used the chi square test to assess the association between qualitative variables. The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS Statistics version 25.00 (IBM Corp; Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

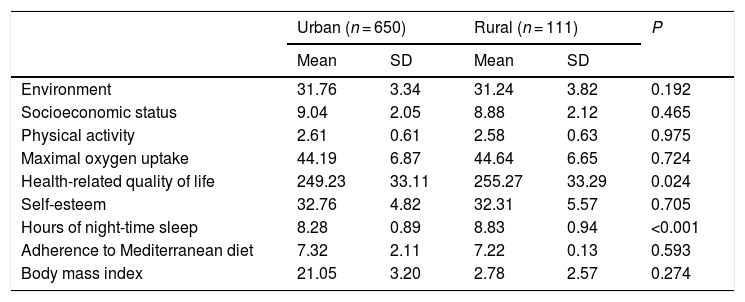

ResultsTable 1 presents the results of the analysis of environmental factors, SES, PA and VO2 max, HRQoL, self-esteem, hours of sleep, diet and body mass index in urban vs rural settings. We found significantly higher HRQoL scores and greater duration of night-time sleep in students that lived in rural areas.

General characteristics of the sample by type of residential setting.

| Urban (n = 650) | Rural (n = 111) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Environment | 31.76 | 3.34 | 31.24 | 3.82 | 0.192 |

| Socioeconomic status | 9.04 | 2.05 | 8.88 | 2.12 | 0.465 |

| Physical activity | 2.61 | 0.61 | 2.58 | 0.63 | 0.975 |

| Maximal oxygen uptake | 44.19 | 6.87 | 44.64 | 6.65 | 0.724 |

| Health-related quality of life | 249.23 | 33.11 | 255.27 | 33.29 | 0.024 |

| Self-esteem | 32.76 | 4.82 | 32.31 | 5.57 | 0.705 |

| Hours of night-time sleep | 8.28 | 0.89 | 8.83 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Adherence to Mediterranean diet | 7.32 | 2.11 | 7.22 | 0.13 | 0.593 |

| Body mass index | 21.05 | 3.20 | 2.78 | 2.57 | 0.274 |

SD, standard deviation.

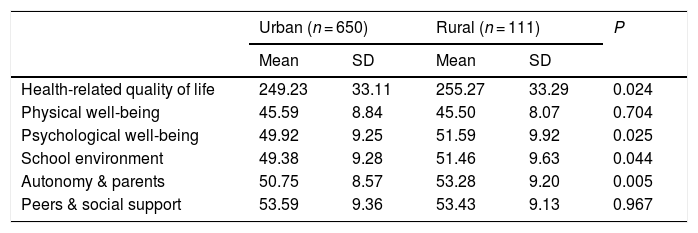

Table 2 summarises the results obtained for HRQoL, overall and in its 5 dimensions. Adolescents in urban areas scored significantly lower in overall HRQoL. Specifically, adolescents in urban areas scored significantly lower in the psychological well-being, school environment and autonomy & parents dimensions.

Health-related quality of life by type of residential setting.

| Urban (n = 650) | Rural (n = 111) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Health-related quality of life | 249.23 | 33.11 | 255.27 | 33.29 | 0.024 |

| Physical well-being | 45.59 | 8.84 | 45.50 | 8.07 | 0.704 |

| Psychological well-being | 49.92 | 9.25 | 51.59 | 9.92 | 0.025 |

| School environment | 49.38 | 9.28 | 51.46 | 9.63 | 0.044 |

| Autonomy & parents | 50.75 | 8.57 | 53.28 | 9.20 | 0.005 |

| Peers & social support | 53.59 | 9.36 | 53.43 | 9.13 | 0.967 |

SD, standard deviation.

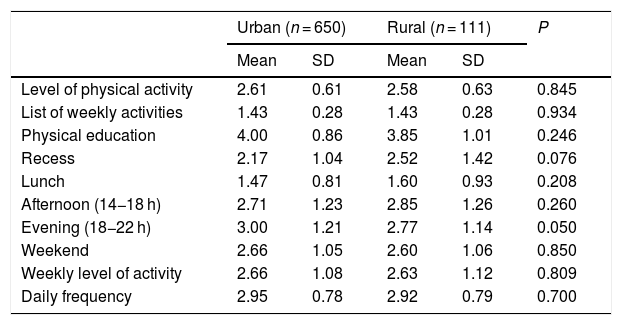

Table 3 presents the level of PA overall and at different times of day and of the week. Although we did not find significant differences in the overall level of PA, we did find that urban adolescents were more likely to be active in the evening, between 6 pm and 10 pm. Active travel to school and participation in organised extracurricular sports activities were also more frequent in urban adolescents (71.7% vs 60.4% of rural adolescents).

Level of physical activity by type of residential setting.

| Urban (n = 650) | Rural (n = 111) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Level of physical activity | 2.61 | 0.61 | 2.58 | 0.63 | 0.845 |

| List of weekly activities | 1.43 | 0.28 | 1.43 | 0.28 | 0.934 |

| Physical education | 4.00 | 0.86 | 3.85 | 1.01 | 0.246 |

| Recess | 2.17 | 1.04 | 2.52 | 1.42 | 0.076 |

| Lunch | 1.47 | 0.81 | 1.60 | 0.93 | 0.208 |

| Afternoon (14−18 h) | 2.71 | 1.23 | 2.85 | 1.26 | 0.260 |

| Evening (18−22 h) | 3.00 | 1.21 | 2.77 | 1.14 | 0.050 |

| Weekend | 2.66 | 1.05 | 2.60 | 1.06 | 0.850 |

| Weekly level of activity | 2.66 | 1.08 | 2.63 | 1.12 | 0.809 |

| Daily frequency | 2.95 | 0.78 | 2.92 | 0.79 | 0.700 |

SD, standard deviation.

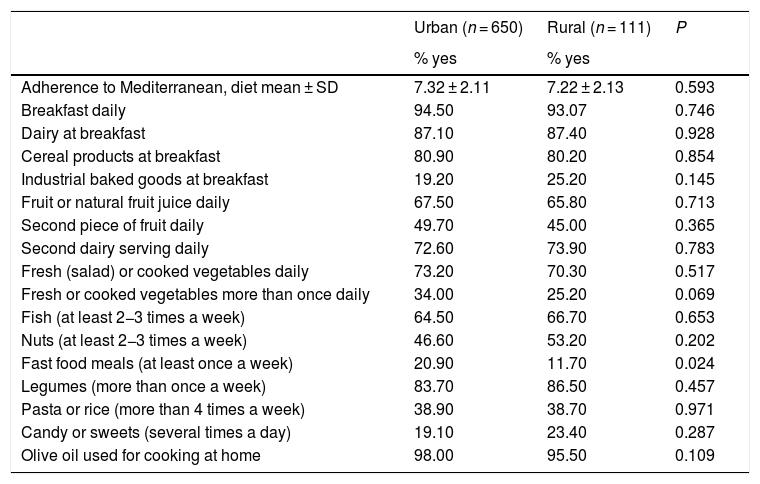

Lastly, Table 4 presents the results of the assessment of adherence to the Mediterranean diet. We did not find differences in overall adherence, but found a higher frequency of fast food consumption in urban adolescents.

Adherence to Mediterranean diet by residential setting.

| Urban (n = 650) | Rural (n = 111) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % yes | % yes | ||

| Adherence to Mediterranean, diet mean ± SD | 7.32 ± 2.11 | 7.22 ± 2.13 | 0.593 |

| Breakfast daily | 94.50 | 93.07 | 0.746 |

| Dairy at breakfast | 87.10 | 87.40 | 0.928 |

| Cereal products at breakfast | 80.90 | 80.20 | 0.854 |

| Industrial baked goods at breakfast | 19.20 | 25.20 | 0.145 |

| Fruit or natural fruit juice daily | 67.50 | 65.80 | 0.713 |

| Second piece of fruit daily | 49.70 | 45.00 | 0.365 |

| Second dairy serving daily | 72.60 | 73.90 | 0.783 |

| Fresh (salad) or cooked vegetables daily | 73.20 | 70.30 | 0.517 |

| Fresh or cooked vegetables more than once daily | 34.00 | 25.20 | 0.069 |

| Fish (at least 2−3 times a week) | 64.50 | 66.70 | 0.653 |

| Nuts (at least 2−3 times a week) | 46.60 | 53.20 | 0.202 |

| Fast food meals (at least once a week) | 20.90 | 11.70 | 0.024 |

| Legumes (more than once a week) | 83.70 | 86.50 | 0.457 |

| Pasta or rice (more than 4 times a week) | 38.90 | 38.70 | 0.971 |

| Candy or sweets (several times a day) | 19.10 | 23.40 | 0.287 |

| Olive oil used for cooking at home | 98.00 | 95.50 | 0.109 |

SD, standard deviation.

In our study, HRQoL scores were significantly higher in adolescents living in rural areas, which was consistent with the findings of studies at the international level.22 In addition, the analysis of the different dimensions of HRQoL revealed that adolescents in rural areas scored significantly higher in the psychological well-being, school environment and autonomy & parents dimensions. When it comes to psychological well-being, it is believed that the risk of developing mental health problems and psychiatric disorders is higher in urban areas.23 These disorders seem to be influenced by physical factors (pollution, population density, type of home or residential setting) and social factors (stress, social isolation, pace of life) that may be less favourable in urban areas, which could explain our findings.9,10 In addition, the type of setting and the characteristics of the immediate environment (greenery, parks and water bodies),11 the perceived air pollution or having contact with nature on a regular basis are also associated with HRQoL.24

Adolescents in urban areas also scored lower in the school environment dimension. The previous literature shows that adolescents in urban areas are more likely to experience academic anxiety, which has an impact on the relationship of students to the school environment.25 The perception of belonging to the school also seems to be weaker in urban areas, reflecting social rejection and problems with peers and instructors.26 The higher frequency of bullying and greater insecurity in urban schools,27 combined with a lesser participation in school activities, could also have a negative impact on school adjustment.28

When it came to the autonomy & parents dimension, the lower score of adolescents in urban areas may be due to higher levels of conflict in urban households.29 Thus, a lower level of attachment to the family is associated with a higher probability of behavioural and psychiatric disorders in adolescents30 and has a deleterious impact on family cohesion.

When it came to the level of PA, we did not find differences in the overall frequency of PA, but found that PA was significantly more frequent in adolescents in urban areas in the 6 pm to 10 pm time range. The lower frequency of sports activities in the rural population could be due to a lack of recreational facilities and the smaller range of athletic activities offered in rural townships.7 In addition, the aforementioned time range is when organised extracurricular sports activities are most likely to take place, which may justify the greater frequency of extracurricular sports in urban adolescents. Similarly, adolescents in urban areas have access to transportation systems that make it easier to travel to recreational facilities to engage in PA.31

The analysis of night-time sleep revealed that adolescents in rural areas slept more hours at night. This was consistent with the findings of Yang et al.,32 who found a higher prevalence of sleep disorders in the urban population and identified living in an urban area, poor parental sleep hygiene and low parental educational attainment as predictors of poor sleep in adolescents. Other aspects, like the use of mobile phones and computers, which seems significantly higher in urban populations,33 and noise and other environmental factors34 may also contribute to the observed differences.

As regards adherence to the Mediterranean diet, we did not find significant differences in overall adherence, an aspect on which results in the previous literature have been contradictory.16,35 Still, we did find a significantly higher frequency of fast food consumption in adolescents in urban areas. Factors that may have contributed to the higher frequency of fast food restaurant patronage by urban adolescents are the greater density of fast food restaurants and the closer proximity to the home in urban areas.36

There are limitations to our study, as there were fewer participants from rural settings compared to urban settings. Although this resulted from the relative proportions of the population under study, the lower frequency of rural participants could have affected some of the results, and in future research, it may be beneficial to recruit larger samples in rural settings. Another limitation is that some of the results were obtained through the use of self-report instruments, which may be a source of bias due to their subjective nature. Thus, a possible improvement in the future could be the use of accelerometers or food diaries to obtain more objective data. Nevertheless, the validity and reliability of these instruments have been demonstrated in previous studies conducted in similar populations. Lastly, we were unable to establish causality due to the cross-sectional design of the study, and performance of longitudinal studies could help interpret the observed differences.

Adolescents in rural areas reported longer duration of sleep and scored higher in HRQoL, overall and in the psychological well-being, school environment and autonomy & parents dimensions. The lower scores found in the urban population evince the need to implement strategies to counteract the deleterious impact on HRQoL of the physical and sociodemographic characteristics of these areas: noise, contamination, fast pace, etc. On the other hand, when it came to lifestyle habits, while we did not find overall differences in PA and adherence to the Mediterranean diet, we found that adolescents in urban areas consumed more fast food and tended to engage in PA later in the day, between 6 pm and 10 pm. In light of this, it would be beneficial to offer a wider range of extracurricular athletic activities in rural areas among other efforts to bridge this gap.

FundingThis study was partially funded by the Instituto de Estudios Riojanos (IER) of the Government of La Rioja through resolution no. 55/2018, of 9 July of the Administration of the IER for the awarding of research grants focused on La Rioja for the 2018–2019 period.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Boraita RJ, Alsina DA, Ibort EG, Torres JMD. Hábitos y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: diferencias entre adolescentes de entornos rurales y urbanos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:196–202.