Fever is one of the most frequent reasons for paediatric emergency visits. It may be caused by an invasive bacterial infection in up to 30%1 of cases, and it is important that these patients are identified to initiate treatment early. To this end, we can use laboratory markers of infection such as peripheral white blood cell (WBC) counts, C-reactive protein (CRP) or procalcitonin (PCT), and several studies have concluded that the latter is probably most useful.2 However, the data are scarce for the paediatric age group and there is no evidence on what the optimum time is for its determination.

The aim of our study was to analyse the time at which the diagnostic yield of PCT is highest, as well as the ideal cut-off point to differentiate a severe bacterial infection, and we also compared PCT with other markers of infection.

We conducted a prospective, observational, analytical cohort study at the paediatric emergency department over the course of 12 months. The study included 217 patients (ages 7 days–36 months) presenting with fever without a source of less than 48h of duration on whom a blood test was performed to rule out bacterial infection due to clinical warning signs (general malaise, inadequate reduction of fever, etc.). We excluded children that had been given antibiotics. We collected data for age, duration of fever in hours (categorised by the most common time intervals used in emergency practice: <6, 6–12 and >12h), WBC count, CRP and PCT levels, microbiology tests and final diagnosis (invasive bacterial infection [IBI], localised bacterial infection, and confirmed viral infection). We grouped the PCT and CRP values by risk level. For PCT, the levels were: low risk, under 0.5ng/mL; moderate risk, 0.5–2ng/mL; and high risk, above 2ng/mL. For CRP, they were: low risk, 0–5mg/dL; moderate risk, 5–10mg/dL; and high risk, above 10mg/dL.

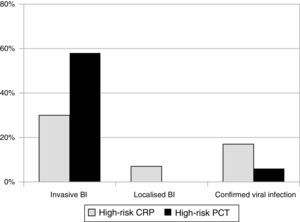

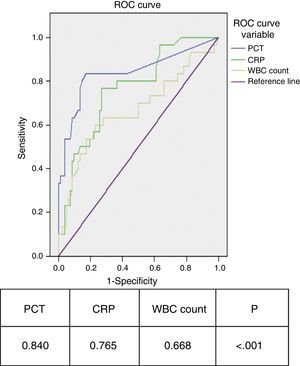

We observed that 80% of IBIs were associated with PCT levels above 2ng/mL between 6 and 12h since fever onset. At this cutoff, specificity was 100% for the 3 time intervals (no viral infection was associated with PCT>2ng/mL), while sensitivity was higher in the 6–12h interval. In this time interval, none of the patients with IBI had a low-risk PCT level, which did happen in 28.6% of patients with IBI in the first 6h of fever. When we compared CRP and PCT (Fig. 1), we observed that 80% of cases with PCT values above 2ng/mL corresponded to bacterial infections, while 87.1% of cases with low-risk PCT values corresponded to viral infections. Meanwhile, a CRP value above 10mg/dL identified only 58% of severe bacterial infections, while 40% of severe bacterial infections were associated with low-risk CRP values in all time intervals. We computed the ROC curves for PCT, CRP and WBC count, and the area under the curve was significantly larger for PCT (Fig. 2). The optimum PCT cut-off value for diagnosing IBI was 0.55ng/mL, which showed a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 85%.

There is a debate as to which markers of infection should be chosen and when they ought to be assessed in cases of fever without a source. Their appropriate use would improve the clinical management of infectious diseases and the rational use of laboratory resources. The results of our study show that PCT offers the best diagnostic yield between 6 and 12h since onset of fever, and confirms that PCT is a better parameter for early assessment of invasive bacterial infections in the first few hours compared to CRP.

Different studies in the literature refer to the duration of fever and its relationship with infection markers in paediatric practice,3,4 but the results of this study, which has a prospective design, establish more accurate boundaries for the time interval in which PCT measurement has the best yield. As for comparing PCT and CRP, the literature review by Marín et al5 obtained an area under the ROC curve for PCT in severe bacterial infections similar to the one found in our study, and higher than the one for CRP. Another study confirmed the superiority of PCT over WBC counts as a marker of serious bacterial infections.6 We have concluded that PCT facilitates the early detection of bacterial infections, with the associated benefits of early initiation of treatment and the subsequent reduction in complications, and that the optimum time range to determine its levels is between 6 and 12h since the onset of symptoms. Normal PCT values allow the optimisation of health care resources.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz Aguilar G, Domingo Triadó I, Benito M, Montesinos Sanchis E. Procalcitonina y síndrome febril precoz: ¿cuándo nos ofrece mayor rentabilidad diagnóstica? An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:58–60.

Previous presentations: This study was presented at the XXVIII Congreso de la Asociación Valenciana de Pediatría, June 15–16, 2012, Benicassim, Spain. Also at the 62 Congreso de la Asociación Española de Pediatría, June 6–8, 2013, Seville, Spain.