Primary lymphoedema is a rare disease, usually with onset in prepubertal girls, and its prevalence ranges between 1/6000 and 1/100000 in the population.1,2

It is caused by abnormal angiogenesis during embryonic development, usually due to mutations in genes responsible for it.2 In up to 80% of cases it manifests in the lower extremities, although it can involve the upper extremities, face and genitals. Focal lymphatic abnormalities lead to an accumulation of lymph that, when sustained, stimulates fibrosis and produces a localised, chronic and progressive oedema. In the early stages, the oedema is not associated with pain, warmth, erythema or functional impairment.

In 1934, Allen classified primary lymphoedema based on the age of onset into congenital, praecox and tarda.2 Recently, Connell et al.2 proposed a new classification that took into account the different clinical presentations and known mutations, giving rise to a complex diagnostic algorithm that encompassed 26 possible diagnoses.

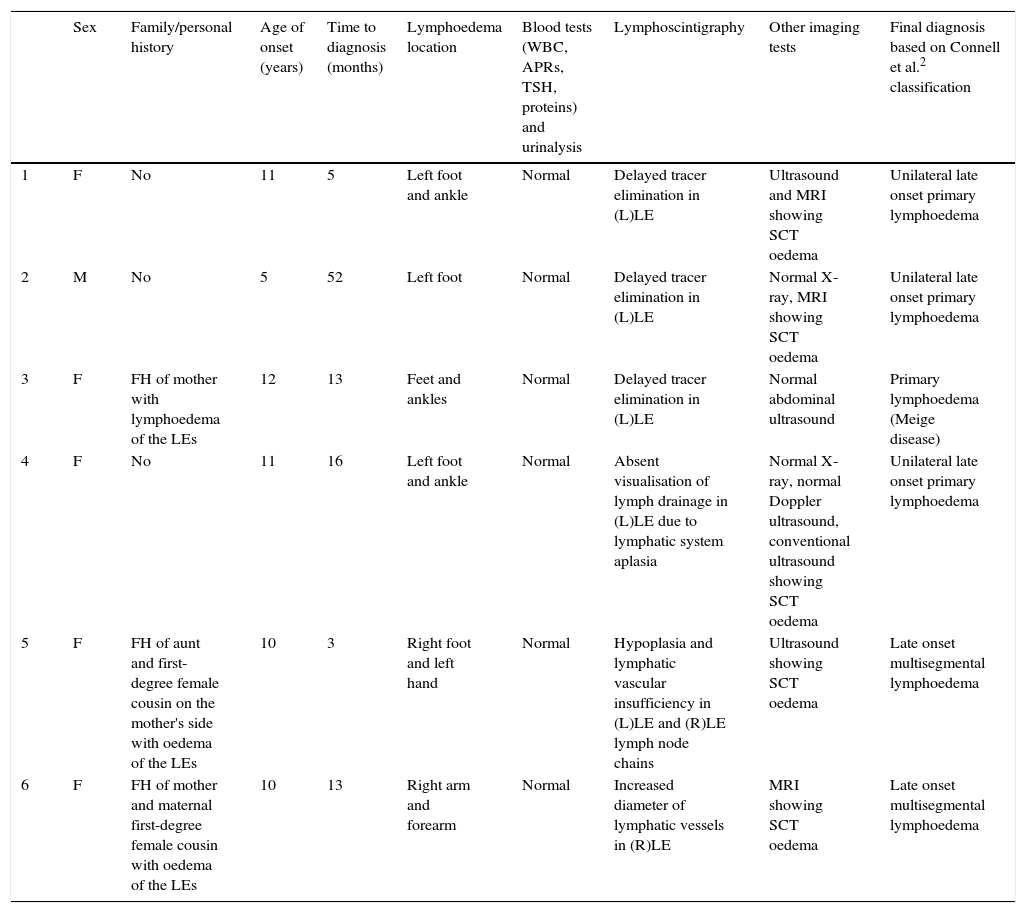

We present the cases of six patients with primary lymphoedema diagnosed in our centre, whose clinical and demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Most of the patients were female, and the age of onset ranged between 5 and 12 years (median, 10.5). None of the patients had associated malformations or a relevant personal history. Fifty percent had a family history of lymphoedema. The time elapsed from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis ranged between 3 months and 4.3 years (median, 9 months). Patients were referred to a specialist to rule out arthritis as the cause of the swelling of the hand or dorsum of the foot. None of the patients reported arthralgia, morning stiffness or functional impairment, and, as is characteristic of lymphoedema, the swelling improved with night rest and worsened with standing. Physical examination found soft tissue oedema in all patients, with no abnormalities in the joints. The results of the blood panel (blood counts, acute phase reactants, TSH, albumin, total protein) and the routine urinalysis were also normal.

Demographic, clinical and diagnostic characteristics of patients with a primary lymphoedema diagnosis.

| Sex | Family/personal history | Age of onset (years) | Time to diagnosis (months) | Lymphoedema location | Blood tests (WBC, APRs, TSH, proteins) and urinalysis | Lymphoscintigraphy | Other imaging tests | Final diagnosis based on Connell et al.2 classification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | No | 11 | 5 | Left foot and ankle | Normal | Delayed tracer elimination in (L)LE | Ultrasound and MRI showing SCT oedema | Unilateral late onset primary lymphoedema |

| 2 | M | No | 5 | 52 | Left foot | Normal | Delayed tracer elimination in (L)LE | Normal X-ray, MRI showing SCT oedema | Unilateral late onset primary lymphoedema |

| 3 | F | FH of mother with lymphoedema of the LEs | 12 | 13 | Feet and ankles | Normal | Delayed tracer elimination in (L)LE | Normal abdominal ultrasound | Primary lymphoedema (Meige disease) |

| 4 | F | No | 11 | 16 | Left foot and ankle | Normal | Absent visualisation of lymph drainage in (L)LE due to lymphatic system aplasia | Normal X-ray, normal Doppler ultrasound, conventional ultrasound showing SCT oedema | Unilateral late onset primary lymphoedema |

| 5 | F | FH of aunt and first-degree female cousin on the mother's side with oedema of the LEs | 10 | 3 | Right foot and left hand | Normal | Hypoplasia and lymphatic vascular insufficiency in (L)LE and (R)LE lymph node chains | Ultrasound showing SCT oedema | Late onset multisegmental lymphoedema |

| 6 | F | FH of mother and maternal first-degree female cousin with oedema of the LEs | 10 | 13 | Right arm and forearm | Normal | Increased diameter of lymphatic vessels in (R)LE | MRI showing SCT oedema | Late onset multisegmental lymphoedema |

FH: family history; F: female; (R): right; (L): left; LE: lower extremity; UE: upper extremity; APRs: acute phase reactants; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SCT: subcutaneous tissue; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; M: male.

Most of the patients had been assessed previously in other departments of the hospital (traumatology, plastic surgery, dermatology, emergency), and underwent different imaging tests (conventional ultrasound, Doppler ultrasound, MRI) that revealed the presence of oedema in the subcutaneous tissue.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of lymphoedema is lymphoscintigraphy, which assesses the velocity of the migration of a radioactive tracer through the lymphatic vessels. The tracer is injected in the dermis of an interdigital web space and tracked by a scintillation camera. This is a minimally invasive and reproducible test that can be performed in children. In patients with primary lymphoedema, this method detects absent or delayed tracer migration3 (Fig. 1). In a study conducted in 107 patients with primary lymphoedema, Kinmonth et al. presented the structural abnormalities that could be detected by lymphoscintigraphy and classified them into three categories: aplasia (absence of lymphatic vessels), hypoplasia (small number or size of lymphatic vessels) and hyperplasia (tortuous lymphatic vessels).1 All our patients presented this type of abnormalities in the lymphatic system, and were classified according to the scheme proposed by Connell et al.2 Other imaging techniques that have been used in more recent studies but have not been widely introduced in clinical practice include indocyanine green lymphography,4 which exposes the patient to radiation, and magnetic resonance lymphangiography using gadobenate dimeglumine as the contrast agent,5 which does not involve exposure to radiation and can obtain dynamic sequences, both of which are as efficacious as lymphoscintigraphy in detecting abnormalities in lymph circulation.

The management of primary lymphoedema is mainly conservative, with the first line treatment consisting of manual lymph drainage or compression therapy. Avoidance of prolonged standing, the use compression stockings, and regular physical activity combined with adequate skin care usually suffice in most cases.3 These measures were implemented in all of our patients and succeeded in controlling the lymphoedema. The prognosis of lymphoedema is good, as the disease stabilises in half of the patients (57%),6 although surgical measures are available for the most severe cases.3

Swelling of the extremities in the paediatric age group requires a broad differential diagnosis including traumatic injury, cellulitis, arthritis, venous insufficiency, deep vein thrombosis and primary lymphoedema.3 Knowledge of this condition and its characteristics—painless swelling in the extremities that changes with posture and is not associated with articular pain or limited range of motion—can prevent diagnostic delays as well as unnecessary referrals and diagnostic tests.

Please cite this article as: Barral Mena E, Soriano-Ramos M, Pavo García MR, Llorente Otones L, de Inocencio Arocena J. Linfedema primario fuera del periodo neonatal. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;85:47–49.