To analyse the 2020 international and European recommendations for Paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), highlighting the most important changes and propose lines of development in Spain.

MethodsCritical analysis of the paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council.

ResultsThe most relevant changes in the CPR recommendations for 2020 are in basic CPR the possibility of activating the emergency system after performing the five rescue ventilations with the mobile phone on loudspeaker, and in advanced CPR, bag ventilation between two rescuers if possible, the administration of epinephrine as soon as a vascular access is obtained, the increase in the respiratory rate in intubated children between 10 and 25 bpm according to their age and the importance of controlling the quality and coordination of CPR. In CPR training, the importance of training non-technical skills such as teamwork, leadership and communication and frequent training to reinforce and maintain competencies is highlighted.

ConclusionsIt is essential that training in Paediatric CPR in Spain follows the same recommendations and is carried out with a common methodology, adapted to the characteristics of health care and the needs of the students. The Spanish Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Group should coordinate this process, but the active participation of all paediatricians and health professionals who care for children is also essential.

Analizar las recomendaciones internacionales y europeas de reanimación cardiopulmonar (RCP) pediátrica del 2020, resaltar los cambios más importantes y plantear líneas de desarrollo en España.

MétodosAnálisis crítico de las recomendaciones de reanimación cardiopulmonar pediátrica del European Resuscitation Council.

ResultadosLos cambios más relevantes en las recomendaciones de RCP del año 2020 son: en la RCP básica la posibilidad de activar el sistema de emergencias tras realizar las cinco ventilaciones de rescate con el teléfono móvil en altavoz, y en la RCP avanzada la ventilación con bolsa entre dos reanimadores si es posible, la administración de adrenalina en cuanto se canaliza un acceso vascular, el aumento de la frecuencia respiratoria en los niños intubados entre 10 y 25 rpm de acuerdo a su edad y la importancia de controlar la calidad y coordinación de la RCP. En la formación en RCP se destaca la importancia de la formación de las habilidades no técnicas como el trabajo en equipo, liderazgo y la comunicación y el entrenamiento frecuente para reforzar y mantener las competencias.

ConclusionesEs esencial que la formación en RCP Pediátrica en España siga las mismas recomendaciones y se realice con una metodología común, adaptada a las características de la atención sanitaria y las necesidades de los alumnos. El Grupo Español de Reanimación Cardiopulmonar Pediátrica y Neonatal debe coordinar este proceso, pero es esencial la participación activa de todos los pediatras y profesionales sanitarios que atienden a los niños.

Cardiac arrest (CA) continues to be an important cause of mortality and impairment (chiefly neurologic) in children, although in recent decades the outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have improved significantly.1,2 Education and training on CPR of health care workers and the general population is one of the key factors for increasing survival free of sequelae in children that experience CA.

The aim of this article is to analyse the main international and European guidelines for paediatric life support (PLS) in 2020,3,4 highlighting any relevant changes from the 2015 guidelines,5,6 and to make them available to paediatricians and the general population in Spain. The Spanish PLS guidelines have been adapted from the guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC).7,8

Guideline review processThe International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) used to publish the Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR) every 5 years. Since 2015, the approach changed, and rather than updating the recommendations every 5 years, the Committee instituted an ongoing process in which reviews of specific subjects were made continuously and a summary of all the reviews with publication of new recommendations every 5 years. The first ILCOR recommendations developed through this approach were published in 20203 and were followed by the publication of the ERC guidelines based on them4 and the specific recommendations for CPR of the American Heart Association (AHA).9 We recommend reading the full text of these recommendations.4

Prevention of cardiac arrest4The PLS guidelines of the ERC published in 2021 have changed the approach compared to previous editions, placing greater emphasis on the clinical management of some of the main clinical scenarios in which there is risk of CA (respiratory insufficiency, status asthmaticus, anaphylaxis, shock, status epilepticus, electrolyte disorders, hyperthermia) than in the management of CA per se.4 This review of the management of urgent conditions is not covered in the ILCOR CoSTR 20203 and does not entail significant changes relative to previous recommendations:

- □

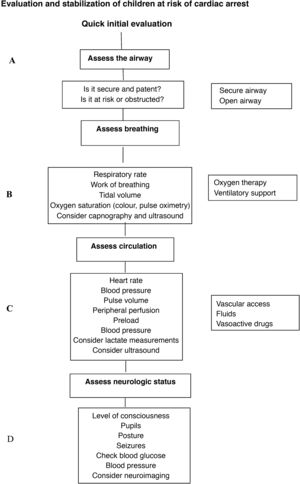

Management of the child at risk of CA. The ERC recommends use of the paediatric assessment triangle or a similar tool for initial evaluation and to implement a structured assessment and intervention protocol following the ABCDE sequence—A (airway), B (breathing), C (circulation), D (disability, neurologic impairment), E (exposure)—performing frequent re-evaluations (Fig. 1).

- □

Septic shock. Fluid volume expansion is not recommended in afebrile children that do not present with shock. It is only recommended in the case of absolute or relative hypovolaemia (septic or anaphylactic shock). We recommend administration of crystalloid or colloid boluses (10−20 mL/kg) with subsequent reassessment, and repeated fluid boluses, up to 40−60 mL/kg, may be needed in the first hour of treatment, unless the patient develops signs of fluid overload. Treatment with vasoactive and inotropic drugs must be tailored to the pathophysiology of each patient and adjusted based on the clinical response. Administration of stress-dose corticosteroids may be considered in children with septic shock that do not respond to fluid therapy or vasoactive drugs.

- □

Volume expansion in haemorrhagic shock secondary to trauma. Although there is no evidence in children, we suggest expansion with reduced and controlled volumes instead of large volumes of crystalloids.

- □

Bradycardia (heart rate < 60 bpm). In the case of bradycardia with adequate peripheral perfusion, contemplate administration of atropine. In the case of a heart rate of less than 60 bpm and poor perfusion, secure the airway and establish adequate ventilation and, if the patient does not improve, initiate chest compressions and administer adrenaline. Transthoracic pacing is indicated in the case of bradycardia secondary to complete heart block or abnormal function of the sinus node, but is not effective in the case of asystole.

The European recommendations for basic PLS maintain the ABC approach (airway, breathing and chest compressions) in the CPR sequence.4 The main changes are:

- □

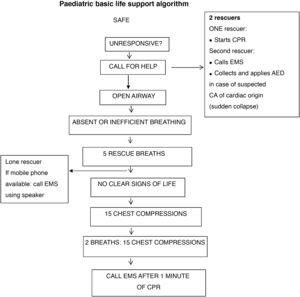

Activation of medical emergency system.4 In the 2015 recommendations, after delivering the first 5 rescue breaths, the rescuer proceeded to assess for signs of life and checking the pulse.5,6 In the 2020 European recommendations, after delivery of the first 5 rescue breaths, in the case of a lone rescuer with a mobile phone with speaker function, the next step is to activate the hands-free option to call emergency medical services (EMS) while continuing to deliver CPR (Fig. 2). If a mobile phone is not available, the bystander should continue CPR for 1 min before leaving the child to contact EMS. The rescuer should only call EMS first in case of witnessing sudden loss of consciousness of suspected cardiac origin, followed by initiation of CPR, as the child could need defibrillation. If there is more than one rescuer, one should start CPR immediately while another calls for help (Fig. 2).

- □

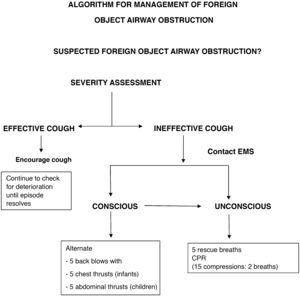

Assessment of breathing. Lay rescuers may assess breathing based solely on the presence or absence of breathing movements (Figs. 3 and 4).

- □

Assessment of CPR effectiveness. To minimise the time without chest compressions, it is recommended that CPR continue without interruption unless there are clear signs of spontaneous circulation (movement, cough) (Figs. 5 and 6).

- □

The ABC sequence used in paediatric basic life support is also used in paediatric advanced life support.

- □

Teamwork. The recommendations emphasise the need of efficient teamwork to allow simultaneous performance of different manoeuvres and reduce the interruption in delivery of chest compressions and ventilation.

- □

Airway and ventilation. If possible, 2 rescuers should open the airway manually and deliver bag-valve-mask ventilation to ensure adequate ventilation. In case of intubation with a cuffed endotracheal tube, maintain the cuff pressure under 20–25 cmH2O.

- □

Respiratory rate. If the patient is not intubated, ventilation coordinated with chest compressions is still recommended (2 breaths per 15 chest compressions). In intubated patients, coordination of ventilation and chest compressions continues to not be recommended, and instead it is recommended that the respiratory rate be increased based on the lower limit of normal for age: <1 year, 25 bpm, 1–8 years, 20 bpm; 8–12 years, 15 bpm; >12 years, 10 bpm. During CPR, use a concentration of inspired oxygen of 100% for ventilation. In patients already on mechanical ventilation, it is possible to maintain it putting the ventilator in volume-controlled mode, disabling triggers and alarms.

- □

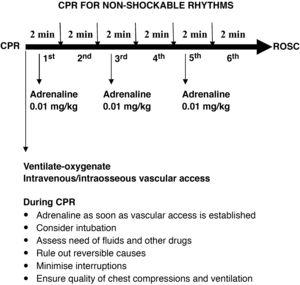

Adrenaline. The most significant change is the recommendation to administer adrenaline (the same dose of 0.01 mg/kg of 1: 10 000 adrenaline) as soon as possible, that is, once vascular access is established, without waiting to complete 3 min of chest compressions and rescue breaths in patients with nonshockable rhythms.

- □

Severe bradycardia. Emphasis on the need to treat severe bradycardia in the absence of vital signs, even if there is a detectable pulse.

- □

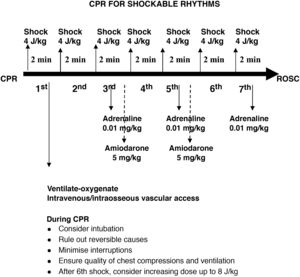

Defibrillation. The standard energy dose of 4 J/kg is still recommended to start defibrillation, introducing the possibility of increasing the dose to 8 J/kg in arrhythmias refractory to more than 5 shocks, never exceeding the recommended dose for adults. Defibrillation with self-adhesive pads is preferred. If unavailable, it is possible to use paddles with preformed gel pads, and charging should be done once the paddles are on the pads and in direct contact with the chest of the patient, contrary to the previous recommendation of charging the paddles away from the patient to minimise the pause in chest compressions. A rationale for this change was not specified.

- □

Pharmacological treatment of shockable rhythms. The 2015 recommendations hold, with administration of adrenaline and amiodarone (dose of 5 mg/kg to a maximum of 300 mg for the initial dose and 150 mg for the second dose) after the third and fifth shocks. Lidocaine can be substituted for amiodarone at a dose of 1 mg/kg. After the fifth shock, adrenaline should be given every 3−5 min.

- □

Quality of CPR. Capnography is not recommended to assess the quality of chest compressions, but it is recommended to verify endotracheal tube placement and for early detection of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). The guidelines do not establish a target invasive blood pressure value for advanced PLS.

- □

Ultrasound. Point-of-care ultrasound may be useful to identify reversible causes of CA, but its use should not interfere with delivery of CPR and should be limited to rescuers with substantial experience in the technique.

- □

Table 1 presents the dosage of the drugs used in PLS.

Table 1.Drugs used in paediatric CPR.

Drug Dose Preparation Route Indication Adrenaline 0.01 mg/kg Diluted in PSS (1 + 9): 0.1 mL/kg IV, IO, ET bolus CA Max: 1 mg ET: 0.1 mg/kg, undiluted Adenosine 1st: 0.2 mg/kg Following immediately with 5−10 mL PSS wash IV, IO bolus SVT Max: 6 mg 2nd: 0.4 mg/kg Max: 12 mg Amiodarone 5 mg/kg Pure IV, IO Refractory VF or PVT Max: 300 mg BOLUS IN CA SVT or VT SLOW RATE IN ALL OTHER CASES Atropine 0.02 mg/kg 0.2 mL/kg IV, IO Vagal bradycardia Max: 1 mg BOLUS Bicarbonate 1 mEq/kg In solution with PSS: 2 mL/kg IV, IO Refractory CA Max: 50 mEq BOLUS Calcium 0.2 mEq/kg= Calcium gluconate 10% 0.4 mL/kg IV, IO at slow rate Hypocalcaemia, hyperkaliaemia, hypermagnesemia Max: 10 mEq Calcium chloride 10% 0.2 mL/kg, in solution Calcium channel blocker intoxication Glucose 0.2−0.4 g/kg Glucose 10%: 2−4 mL/kg IV, IO Documented hypoglycaemia Bolus Lidocaine 1 mg/kg Undiluted IV, IO Refractory VF or PVT Max: 100 mg Bolus Fluids 20 mL/kg PSS IV, IO PEA Rapid rate Hypovolaemia Magnesium 50 mg/kg Undiluted IV, IO Polymorphic VT with torsades de pointes Bolus CA, cardiac arrest; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ET, endotracheal; IO, intraosseous; IV, intravenous; Max, maximum dose; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; PSS, physiological saline solution; PVT, pulseless ventricular tachycardia; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

- □

The ABCD sequence is recommended to establish care priorities and for ongoing assessment.

- □

Oxygenation objectives. Children that experienced short-lived CA and immediately recover consciousness and spontaneous breathing should receive oxygen therapy as needed to achieve a SpO2 greater than 94%. In intubated patients, after the ROSC, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) should be set at 100% until the arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) or partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) can be measured reliably. From that point, the FiO2 should be titrated to achieve a SaO2 of 94%–98% and a PaO2 of 75–100 mmHg. Both hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg) and hyperoxaemia must be avoided. In patients with carbon monoxide poisoning or severe anaemia, in who peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) readings are not as reliable, higher FiO2 settings and more frequent arterial blood gas measurements are recommended.

- □

Ventilation objectives. It is recommended that ventilation starts with respiratory rate and tidal volume settings in the normal range for age in a lung-protection strategy. Initially, ventilator parameters should be set to achieve an arterial PaCO2 in the normal range (35−45 mmHg). Subsequently, capnography can be used to guide adjustment of mechanical ventilation as long as its correspondence with the PaCO2 is verified at regular intervals. In children with chronic pulmonary disease or congenital heart disease with single-ventricle physiology, the goal should be to restore previous PaCO2 values. Patients under therapeutic hypothermia, which may cause hypocapnia, and patients receiving ventilation for management of increased intracranial pressure require more frequent measurement of PaCO2.

- □

Blood pressure (BP). Continuous invasive BP monitoring is recommended to achieve a systolic BP at or above the median for age. Fluids and inotropic or vasopressor drugs should be given in the minimum necessary amounts to reach this target.

- □

Neuroprotection. In patients that remain comatose after ROSC, active control of temperature to maintain a central temperature of 37.5 °C or less is recommended.

- □

Prognosis. Although several factors are associated with the long-term outcome of CA, there is no single one that can be used in isolation to establish the prognosis. The combined use of multiple variables is recommended, including biomarkers and neuroimaging features.

- □

Anticipatory care planning and shared decision making. Although CA is a sudden event, in many cases it is possible to predict its risk, so it is recommended that providers facilitate care planning ahead of time, providing clear information and respecting the autonomy of the patient and legal guardians, including decisions regarding resuscitation (whether to initiate CPR or not in the event of CA) among other treatment decisions. To do so, health care professionals need to hone their communication skills, take into account the values and preferences of patients and their families, involve the latter in the shared decision-making process and, when appropriate, implement withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining treatment protocols while providing palliative care and psychological support.

- □

Criteria to initiate and terminate CPR. Resuscitation should be perceived as a treatment based on criteria. Some criteria are unequivocal, such as any risk to the rescuer, the presence of clear signs of death or a previous agreement not to initiate CPR. Others can guide decision-making, such as persistent asystole after 20 min of advanced CPR in absence of a reversible cause, unwitnessed CA with an initial non-shockable rhythm with a very poor prognosis or existing evidence that CPR would not fit the values or preferences of the patient. In any case, the reasons to not initiate, not prolong or to terminate CPR should be clearly documented.

- □

Research ethics. There is a clear need to obtain scientific evidence to improve the outcomes of CA. This objective involves adapting consent procedures, review by research ethics and establishment of good clinical practice guidelines in addition to involving community stakeholders and health care institutions in the design, funding, performance and dissemination of research.

- □

Education and training in the management of CA are key to improve outcomes. Therefore, current guidelines emphasise the need to improve the efficiency of educational interventions, with adaptation of trainings to specific target groups, integrating new approaches in training and providing training at regular intervals.

- □

Professionals that work with children should get involved. It is recommended that training be delivered by instructors experienced in the use of specific materials (traditional CPR manikins, quality-control devices, advanced simulators, virtual/augmented reality systems, etc.) and with qualifications on non-technical skills such as teamwork, leadership and communication. We recommend frequent refresher trainings and updating of skills. As for the format and content of the courses, we recommend limiting in-person theoretical knowledge sessions, using remote education platforms instead (for autonomous or instructor-guided learning), and study preceding in-person practical skill simulation activities followed by interactive discussion sessions.

- □

Training of adults. Every citizen should know how to activate the chain of survival and initiate basic CPR. Training should include paediatric CPR and the response to foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO). Trainings should be delivered by instructors experienced in teaching laypeople using methodology adapted to the specific needs of the students, and refresher trainings should be conducted at least once a year.

- □

Training of children. The ERC has launched the Kids Save Lives initiative with the goal of having all children learn how to activate the chain of survival and initiate CPR. Training contents must be adapted to the age and physical development of children. It must be included in the school curriculum and be delivered by teachers previously trained in basic life support and using materials designed specifically for the purpose. The ultimate objective is to ensure that future adults know how to respond appropriately to CA in order to improve survival free of neurologic sequelae.

The 2020 guidelines for paediatric and neonatal life support, including the international ILCOR recommendations and the ERC recommendations in Europe, have not introduced significant changes in the resuscitation sequence or techniques. The most significant changes in PLS are the early administration of adrenaline as soon as vascular access is established and the increase in respiratory rate during CPR to 10–25 bpm, depending on age, following intubation. Another aspect to consider is the adaptation of CPR in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Recommendations are increasingly placing emphasis on quality control in CPR and the training of rescuers in non-technical skills, such as leadership, communication and teamwork.

Our efforts to improve paediatric resuscitation outcomes must extend to every setting, starting with training the general population in the prevention of CA and paediatric CPR skills, in which paediatricians play an essential role in collaboration with educators.

At the care setting level, the participation of paediatricians is key in the development of plans to prevent and manage CA in children and providing training in PLS to health care workers based on the specific needs of each care setting. The use of scales to assess the risk of CA and the creation of rapid response teams are both recommended.

When it comes to education, each facility should plan delivery of structured CPR trainings to every professional and at different levels (basic, intermediate and advanced) based on their activity. The Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation recommends that the theoretical education that precedes intermediate and advanced CPR trainings include not only how to identify and assess CA risk, but also how to manage the most common conditions associated with a risk of CA. Another important goal is to develop a continuing education programme based on short practice sessions and scenario simulations with emphasis on assessment of CPR quality and development of coordination and teamwork skills.

Teaching standardised CPR guidelines facilitates learning, improves CPR outcomes and decreases the probability of errors. Therefore, it would be best if all PLS training in Spain was based on the same guidelines and delivered applied a similar methodology, adapted to the specific characteristics of health care and needs of students in the country. The primary objective of Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation should be to coordinate this process,14 and another essential aspect is the active participation of all paediatricians and health care professionals involved in the care of children.

Data availabilityData will be made available on request.

Our open-access data is available via Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5794358) but we were unable to link this data set in the \

- none-

Jesús López-Herce. Paediatric Intensive Care Department. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón. School of Medicine. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Mother-Child Health Research Network (SAMID II). RETICS funded by the National Plan for R+D+I 2013–2016, ISCIII- General Vice Directorate of Research Evaluation and Promotion and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) Ref: RD16/0022/0007. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Ignacio Manrique. Instituto Valenciano de Pediatría. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Custodio Calvo. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Antonio Rodríguez. Section of Paediatrics, Department of Padiatric Intensive, Intermediate and Emergency Care. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela. Clinical Nursing Research Group (CLINURSID), Department of Nursing, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. Instituto de Investigación de Santiago (IDIS). SAMID II Research Network. RETICS funded by the National Plan for R + D+I 2013–2016, ISCIII- General Vice Directorate of Research Evaluation and Promotion and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) Ref: RD16/0022/0007. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Ángel Carrillo. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Valero Sebastián. Centro de Salud Fuente de San Luis. Valencia. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

- none-

Jimena del Castillo. Department of Paediatric Intensive Care. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. SAMID II Research Network. RETICS funded by the National Plan for R + D+I 2013–2016, ISCIII- General Vice Directorate of Research Evaluation and Promotion and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) Ref: RD16/0022/0007. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Eva Civantos. Centro de Salud de Barranco Grande. Tenerife. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Eva Suárez. Centro de Salud Integrado Burriana II. Castellon. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Sara Pons. Department of Paediatrics. Hospital Doctor Peset. Valencia. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

Gonzalo Zeballos. Department of Neonatology. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

- none-

María José Aguayo. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville. Spanish Group on Paediatric and Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

Please cite this article as: López-Herce J, Manrique I, Calvo C, Rodríguez A, Carrillo A, Sebastián V, et al. Novedades en las recomendaciones de reanimación cardiopulmonar pediátrica y lineas de desarrollo en España. An Pediatr. 2022;96:146–146.