Nissen fundoplication (NF) is the most used and effective technique for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in children. The laparoscopic approach (LNF) is safe, with low morbidity and high success rate, although some cases require a conventional approach (CNF). The aim of the study is to compare the results between LNF and CNF in our centre.

Material and methodsA retrospective review was performed on patients <14 years after NF between 2000 and 2015. A comparison was made of the complications, hospital stay, and follow-up for both approaches.

ResultsOf the total 75 NF performed, 49 (65.3%) were LNF, 23 (30.7%) CNF, and 3 (4.0%) reconversions. Concomitant laparoscopic gastrostomy was performed in 10.7%, and open gastrostomy in 5.3% of cases. Prior to NF, 10.7% had a gastrostomy. The mean age was 4 years and 68.7% were male. Of the diagnoses, 36% had encephalopathy, 14.7% hiatal hernia, 5.4% oesophageal atresia, and 5.4% an acute life-threatening event. No differences were found in operation time. More than two-thirds (36%) had complications, which were more frequent in the CNF (OR=3.30, 95% CI: 1.1–9.6). The hospital-stay decreased by 9 days in the LNF (95% CI: 5.5–13.5). Mean follow-up was 26 months (95% CI: 20.9–31.6). Mortality during follow-up was of 5.3% (5 respiratory failure, 1 sudden cardiac death, and 2 due to complications of the encephalopathy), 4.2% required re-fundoplication, 15.8% had symptomatic improvement, and 64.0% had absence of symptoms.

ConclusionsThe LNF is an effective technique for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux, with lower morbidity and shorter hospital stay than CNF. It is recommended as the first surgical option.

La funduplicatura de Nissen (FN) es la técnica más utilizada y con mejores resultados para tratar el reflujo gastroesofágico en niños. El abordaje laparoscópico (FNL) es seguro, con baja morbilidad y alta tasa de éxito, aunque algunos casos precisan abordaje convencional (FNC) o abierto. Nuestro objetivo es comparar los resultados entre la FNC y la FNL en nuestro centro.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de los pacientes <14 años sometidos a FN entre 2000 y 2015. Comparamos ambos abordajes: complicaciones, estancia hospitalaria y seguimiento.

ResultadosSe realizaron 75 FN; 49 (65,3%) FNL, 23 (30,7%) FNC y 3 (4,0%) reconversiones. Se asoció gastrostomía por laparoscopia en el 10,7% y abierta en el 5,3%. El 10,7% portaban gastrostomía previamente a la FN. La edad media fue de 4 años, y el 68,7% fueron varones. El 36% presentaron algún grado de encefalopatía, el 14,7% hernia hiatal, el 5,4% antecedente de atresia esofágica intervenida y el 5,4% al menos un episodio aparentemente letal. No encontramos diferencias significativas en la duración de la intervención entre ambos abordajes. El 36% presentaron complicaciones, más frecuente en la FNC: OR=3,30 (IC 95%: 1,1-9,6). La estancia disminuyó en 9 días en la FNL (IC 95%: 5,5-13,5). El seguimiento medio fue de 26meses (IC 95%: 20,9-31,6), con 10,7% fallecimientos (5 insuficiencias respiratorias, una muerte súbita y 2 por su encefalopatía); el 4,2% precisaron nueva funduplicatura, el 15,8% mostraron mejoría sintomática y el 64,0%, ausencia de síntomas.

ConclusionesLa FNL es una técnica adecuada para el tratamiento del reflujo gastroesofágico, con menor morbilidad y menor estancia que la FNC, por lo que se recomienda como primera opción terapéutica.

Nissen fundoplication (NF) is the most commonly performed surgical procedure for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in children. The laparoscopic approach (LNF) is an effective and safe technique for the treatment of GERD and is currently considered the gold standard. In most cases, a laparoscopic approach is feasible and is considered the treatment of choice, although there are specific cases that require an open or conventional Nissen fundoplication (CNF). Both approaches have good outcomes, improving quality of life and symptom control. Our objective was to compare the results obtained with both techniques in our hospital.

Materials and methodsRetrospective review of the electronic health records of 75 patients, all aged less than 14 years, that underwent NF consecutively in our hospital between February 2000 and January 2015. Conventional NF was performed following customary procedure or under the supervision of three surgeons, and LNF was performed by or under the supervision of a surgeon. The first and second assistants in either approach could be a paediatric surgeon or a fifth-year paediatric surgery resident.

The variables under study were sex, age, diagnosis, surgical history, preoperative symptoms, imaging and laboratory tests, surgical approach, surgery duration, complications of surgery, length of stay, followup, outcome of surgery, reoperation and mortality.

Later on, we performed an analysis of subsets by surgical approach (LNF and CNF), age group (<2 and ≥2 years) and presence or absence of neurologic impairment. We compared durations of surgery, intraoperative and postoperative complications, length of stay and outcomes of the procedure during followup.

ResultsSurgery was performed in a total of 51 (68.0%) boys and 24 (32.0%) girls aged 1 month to 14 years, with a mean age of 5±4.5 years. Of these patients, 16 (22.7%) were aged less than 24 months, with a mean age of 12±7 months.

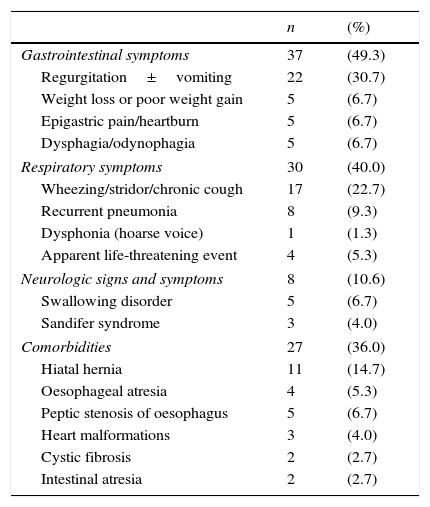

Some of the most relevant features of the clinical history included encephalopathy in 27 patients (36%), hiatal hernia in 11 (14.7%), oesophageal atresia in four (5.4%) and apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) in four (5.4%). The most frequent preoperative symptoms were gastrointestinal (Table 1).

Most frequent symptoms and associated diseases in patients with GERD that underwent surgery.

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 37 | (49.3) |

| Regurgitation±vomiting | 22 | (30.7) |

| Weight loss or poor weight gain | 5 | (6.7) |

| Epigastric pain/heartburn | 5 | (6.7) |

| Dysphagia/odynophagia | 5 | (6.7) |

| Respiratory symptoms | 30 | (40.0) |

| Wheezing/stridor/chronic cough | 17 | (22.7) |

| Recurrent pneumonia | 8 | (9.3) |

| Dysphonia (hoarse voice) | 1 | (1.3) |

| Apparent life-threatening event | 4 | (5.3) |

| Neurologic signs and symptoms | 8 | (10.6) |

| Swallowing disorder | 5 | (6.7) |

| Sandifer syndrome | 3 | (4.0) |

| Comorbidities | 27 | (36.0) |

| Hiatal hernia | 11 | (14.7) |

| Oesophageal atresia | 4 | (5.3) |

| Peptic stenosis of oesophagus | 5 | (6.7) |

| Heart malformations | 3 | (4.0) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 | (2.7) |

| Intestinal atresia | 2 | (2.7) |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The diagnostic tests that led to confirmation of GERD were gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy and histopathological examination compatible with oesophagitis in 33 patients (44.0%), measurement of pH with evidence of acid reflux in 33 (44.0%), scintigraphy with evidence of lung involvement in eight (10.7%), impedance recording with evidence of reflux in 4 (5.3%) and upper GI series that found hiatal hernia in 11 (14.7%). Main reasons for surgery included poor symptom control with pharmacological treatment, presence of symptomatic hiatal hernia and occurrence of ALTE in infants.

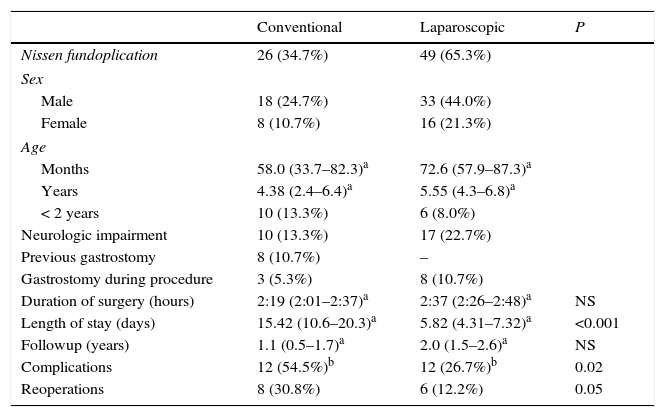

Seventy-two NFs and three repeat NFs were performed, of which 49 (65.3%) were laparoscopic, 23 (30.7%) conventional and three (4.0%) required conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery (Table 2). Gastrostomy had been performed prior to NF in 10.7%, and was performed during NF in 16.0%. During one conventional surgery and one laparoscopic surgery, the oesophagus was perforated accidentally during dissection, which was managed with a basic closure with absorbable suture. These were the only documented intraoperative complications.

Comparison of CNF and LNF.

| Conventional | Laparoscopic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nissen fundoplication | 26 (34.7%) | 49 (65.3%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 18 (24.7%) | 33 (44.0%) | |

| Female | 8 (10.7%) | 16 (21.3%) | |

| Age | |||

| Months | 58.0 (33.7–82.3)a | 72.6 (57.9–87.3)a | |

| Years | 4.38 (2.4–6.4)a | 5.55 (4.3–6.8)a | |

| < 2 years | 10 (13.3%) | 6 (8.0%) | |

| Neurologic impairment | 10 (13.3%) | 17 (22.7%) | |

| Previous gastrostomy | 8 (10.7%) | – | |

| Gastrostomy during procedure | 3 (5.3%) | 8 (10.7%) | |

| Duration of surgery (hours) | 2:19 (2:01–2:37)a | 2:37 (2:26–2:48)a | NS |

| Length of stay (days) | 15.42 (10.6–20.3)a | 5.82 (4.31–7.32)a | <0.001 |

| Followup (years) | 1.1 (0.5–1.7)a | 2.0 (1.5–2.6)a | NS |

| Complications | 12 (54.5%)b | 12 (26.7%)b | 0.02 |

| Reoperations | 8 (30.8%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.05 |

CNF, conventional Nissen fundoplication; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; NS, not significant.

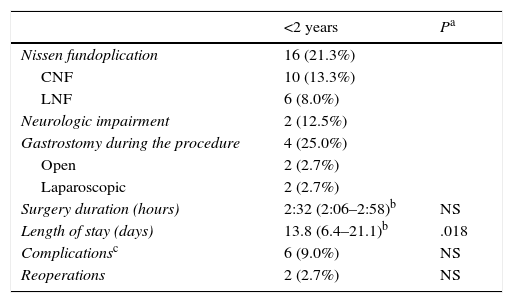

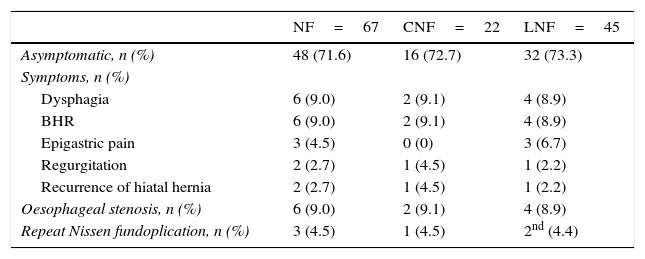

The mean duration of followup was 26 months (95% CI, 20.8–31.2). Thirty-six percent of patients developed complications, which were more frequent in patients that underwent CNF: odds ratio (OR) of 3.30 (95% CI, 1.1–9.6). In general, the most frequent complications of CNF included two (2.7%) cases of oesophageal stenosis managed with high-pressure balloon dilatation, two (2.7%) cases of evisceration that required primary closure, and one case of intestinal subocclusion that responded well to conservative management. The complications of LNF included four (5.3%) cases of oesophageal stenosis managed by high-pressure balloon dilatation. We did not find a difference in the number of complications or repeat fundoplication in patients aged less than 2 years, although length of stay was longer in this age group than in the rest of patients (Table 3). The symptoms reported during followup were dysphagia in six patients (8%), epigastric pain/heartburn in four (5.3%), irritable bowel that improved gradually with medical treatment in two (2.7%) and difficulty passing gas in one (1.3%) (Table 4).

Nissen fundoplication in children aged less than 2 years (n=16).

| <2 years | Pa | |

|---|---|---|

| Nissen fundoplication | 16 (21.3%) | |

| CNF | 10 (13.3%) | |

| LNF | 6 (8.0%) | |

| Neurologic impairment | 2 (12.5%) | |

| Gastrostomy during the procedure | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Open | 2 (2.7%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 2 (2.7%) | |

| Surgery duration (hours) | 2:32 (2:06–2:58)b | NS |

| Length of stay (days) | 13.8 (6.4–21.1)b | .018 |

| Complicationsc | 6 (9.0%) | NS |

| Reoperations | 2 (2.7%) | NS |

CNF, conventional Nissen fundoplication; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; NS, not significant.

GERD symptoms during followup (n=67).

| NF=67 | CNF=22 | LNF=45 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic, n (%) | 48 (71.6) | 16 (72.7) | 32 (73.3) |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Dysphagia | 6 (9.0) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| BHR | 6 (9.0) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| Epigastric pain | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.7) |

| Regurgitation | 2 (2.7) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (2.2) |

| Recurrence of hiatal hernia | 2 (2.7) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (2.2) |

| Oesophageal stenosis, n (%) | 6 (9.0) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| Repeat Nissen fundoplication, n (%) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | 2nd (4.4) |

BHR, bronchial hyperresponsiveness; CNF, conventional Nissen fundoplication; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; NF, Nissen fundoplication.

a One patient transferred from another hospital with a previous LNF.

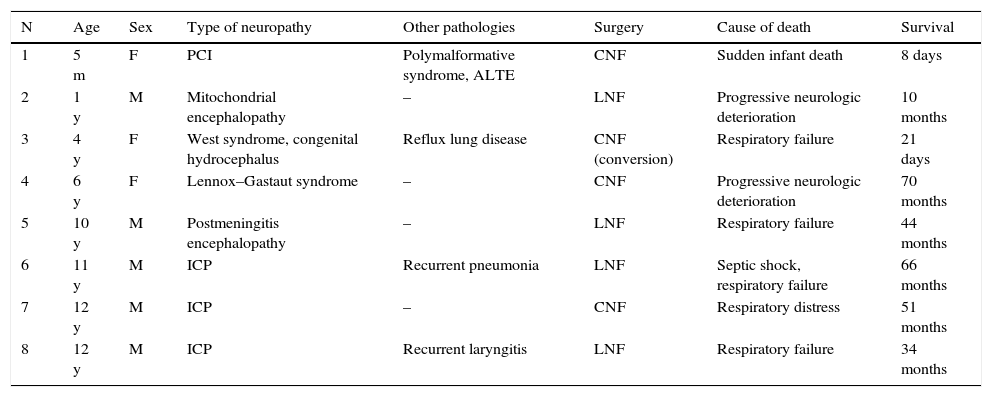

Eight deaths (10.7%) were reported during followup. All were in patients that had underlying encephalopathies (Table 5). Two (2.7%) died in the first month post surgery: the first one due to progressive respiratory dysfunction, and the second from sudden infant death. The rest had a mean survival of 46±22 months post surgery. The cause of death was progressive respiratory failure associated with infectious disease in four patients, and complications of the underlying neurologic disease in two.

Patients with neurologic impairment that died during followup.

| N | Age | Sex | Type of neuropathy | Other pathologies | Surgery | Cause of death | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 m | F | PCI | Polymalformative syndrome, ALTE | CNF | Sudden infant death | 8 days |

| 2 | 1 y | M | Mitochondrial encephalopathy | – | LNF | Progressive neurologic deterioration | 10 months |

| 3 | 4 y | F | West syndrome, congenital hydrocephalus | Reflux lung disease | CNF (conversion) | Respiratory failure | 21 days |

| 4 | 6 y | F | Lennox–Gastaut syndrome | – | CNF | Progressive neurologic deterioration | 70 months |

| 5 | 10 y | M | Postmeningitis encephalopathy | – | LNF | Respiratory failure | 44 months |

| 6 | 11 y | M | ICP | Recurrent pneumonia | LNF | Septic shock, respiratory failure | 66 months |

| 7 | 12 y | M | ICP | – | CNF | Respiratory distress | 51 months |

| 8 | 12 y | M | ICP | Recurrent laryngitis | LNF | Respiratory failure | 34 months |

ALTE, apparent life-threatening event; CNF, conventional Nissen fundoplication; ICP, infantile cerebral palsy; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.

Last of all, 49 (64.0%) patients reported having no symptoms and did not require ongoing medication or needed only symptomatic treatment, while 12 (15.8%) reported an overall improvement in symptoms with reduced need for medication. Repeat fundoplication was required in three (4.2%) patients: one patient that had underwent conventional surgery with symptomatic recurrence of hiatal hernia, who needed repetition of CNF and repair of the hiatal defect; the second patient had previously undergone laparoscopic surgery and experienced recurrence of hiatal hernia, requiring a repeat LNF with repair of the hiatal defect; the last patient had been initially operated on in a different hospital (LNF) and sought care at our hospital due to significant respiratory symptoms, which led to the decision to perform a repeat NF with a laparoscopic approach.

A survey of the parents or guardians of the patients was performed during the followup, assessing the outcome of fundoplication in relation to quality of life, with 81% of the families reporting “very good” outcomes, especially in patients that had experienced respiratory symptoms.

DiscussionNissen fundoplication is a surgical procedure that is frequently performed to treat GERD in children, including those younger than 2 years.1 At present, NF is considered a safe and efficacious intervention for symptom control and improving quality of life, and is associated with a very low rate of recurrence in the first 10 years.2–4 The treatment of GERD usually involves a step-wise approach, starting with diet and lifestyle changes and with anti-acid treatment with a focus on symptom management, reserving surgery for refractory cases.5,6 The most frequent symptoms are gastrointestinal, although patients with respiratory symptoms usually achieve better symptom control after NF.7 Patients with neurologic comorbidities require special consideration, as they usually present with swallowing difficulties and GERD that cannot be controlled with conservative treatment.8–10 Patients with hiatal hernia, infants that experience ALTEs or recurrent breath-holding spells are usually eligible for surgery and have good outcomes.11 However, the indication for NF is ultimately based on the judgement of each surgeon or institution.

At present, LNF is considered the first-line surgical approach in children.11 One of the criteria for the open approach is previous abdominal surgery. In our case series, CNF was chosen for patients that had a gastrostomy; in three cases, the initial approach was laparoscopic, but conversion was necessary due to adhesions from previous surgery. Surgery was also chosen for the treatment of patients with a history of abdominal surgery for malformations of the gastrointestinal tract, including oesophageal or duodenal atresia.

It is believed that LNF is as effective as its alternative, CNF, in resolving symptoms associated with GERD.2–5,12 However, several studies suggest that patients that undergo LNF have shorter lengths of stay, earlier feeding tolerance, and a lower rate of complications.12 In our experience, the length of stay was considerably shorter, and we found a higher risk of postoperative complications in the CNF group. The complications associated most frequently with CNF are incisional hernia, fundal wrap defect,13 intestinal motility problems, oesophageal stenosis, prolonged intubation and pneumonia.10 We ought to mention that out of all the patients in our series that had oesophageal stenosis requiring balloon dilatation after NF, five already had the peptic stenosis before surgery. We must also take into account the complications associated with gastrostomy and its management, and that patients with neurologic comorbidities experience more complications due to their underlying disease.9,10 All the patients that died in our series had neurologic impairment, and their causes of death were associated with their underlying disease, despite achievement of adequate symptom control.

Recurrence of GERD has been associated with congenital anomalies, such as diaphragmatic hernia and oesophageal atresia,8 and also with neurologic impairment.11,14,15 Hiatal hernia was the reason for two of the three repeat fundoplications performed in our patients.

With NF, subjective symptom control was achieved in a large percentage of patients, which was consistent with the findings of other studies.2

In the past 15 years, our hospital has performed NF for the control and treatment of GERD in children with positive outcomes. Our findings were consistent with the existing literature, with achievement of symptom control in most patients, low morbidity, and a low rate of recurrence. Patients with neurologic impairment, that had had ALTEs or with a history of oesophageal atresia are suitable candidates for surgery but have a high risk of postoperative morbidity. In light of these findings, we find LNF an attractive approach on account of its shorter length of stay, decreased morbidity and good symptom control, and consider it the first-line surgical approach for the treatment of GERD.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Betancourth-Alvarenga JE, Garrido Pérez JI, Castillo Fernández AL, Murcia Pascual FJ, Cárdenas Elias MA, Escassi Gil A, et al. Manejo del reflujo gastroesofágico en niños. Funduplicatura de Nissen convencional y por laparoscopia en los últimos 15 años en un centro especializado. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;86:220–225.

Previous presentation: This study was presented at the LIV Congress of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Surgery; 2015; Alicante, Spain.