Virtual consultations (VCs), virtual medical visits (VMVs) and telemedicine are on the rise, especially for adult hospital-based care1 and dermatology clinics. Although the scope of these services in paediatrics has been defined,2 there is little experience with these modalities of paediatric care in our region. The VC is a tool that allows primary care (PC) paediatricians to consult on specific aspects with hospital-based paediatric specialists. Unlike VMVs, the interaction is between health professionals. Its purposes are to improve the appropriateness of referrals, to empower PC paediatricians and to improve patient access to hospital-based care. The aim of setting up VCs is to facilitate communication between providers and respond to complaints presented at the PC level within shorter timeframes compared to conventional care pathways. The patient can benefit from these services without having to travel, so that school and work do not need to be missed,3 and they can be particularly useful in rural areas. Shorter waiting times may reduce diagnostic delay in certain diseases. We present the results of a pilot project introduced in the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga in collaboration with the PC District of Malaga with the participation of 13 primary care centres.

We established which diseases had characteristics that made them more suitable for virtual consultation, although PC paediatricians could consult on any issue. The study included 13 primary care centres, some of which are near the hospital and other that are at greater distance and in rural areas. We set up a weekly schedule for these consultations. We established a maximum wait time to respond from the hospital of 7 days. After 4 months, we submitted questionnaires to assess the satisfaction of the colleagues in PC that made a VC during the period under study by means of Likert scales.

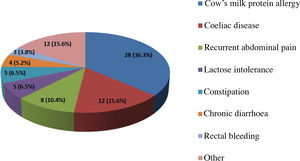

A total of 77 VCs were held in 28 weeks, corresponding to a volume of 10.1% relative to the total number of first visits (763) received in that period. We found a clear improvement in the first visits to successive visits ratio, which decreased from 2.95 at the time VCs started (October 1, 2019) to 2.28 in March 2020; a change that could be attributed to improved referrals and shorter wait times after initiation of VCs. In the opinion of the paediatric gastroenterologist, 15 referrals (19.5%) met the criteria for in-person assessment from the outset. Fig. 1 presents the diseases that led to referral. The reasons for VCs were diverse: doubts regarding drug prescription, the approach to diagnosis, consultation regarding laboratory results such as cholesterol levels or elevation of antigliadin antibodies, follow-up of chronic patients, etc. In 64 cases (83.1%) the concern was resolved, shortening the time to referral or through an electronic prescription. In the group of patients that required referral to in-person care, the performance of diagnostic tests decreased by 18.4%. The PC paediatrician needed to do more than one consultation or referral for in-person care for the same complaint in only 1 case. The low frequency of repeated consultation may be an indirect measure of the safety of this method, an aspect that has been previously analysed in other telemedicine systems.3

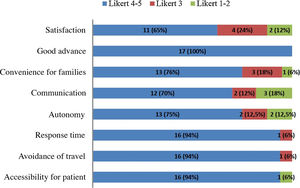

We sent the questionnaire to 20 PC paediatricians, and 17 responded. More than 75% of respondents reported being satisfied or very satisfied with certain aspects of the VCs, and had a positive perception of the accessibility, the waiting times, the development of autonomy in the follow-up of certain diseases and the convenience of the care offered to the patient by avoiding travel to the site and therefore having to miss school or work (Fig. 2). The perceived drawbacks were problems with the software and problems with communication regarding the appropriate timing and type of patient for VCs; this evinced the need to make improvements, in addition to extending the programme to every PC centre in the catchment area of the hospital to reach stronger conclusions. We did not find differences in participation between PC centres based on their distance from the hospital.

The period that we are experiencing due to the global pandemic has prompted a sharp increase in the number of professionals that are working remotely to prevent the transmission and spread of the virus.4 As has been the case in adult care,5 the development of paediatric VCs is an emerging reality brought on by changing times, and while under some circumstances the physical examination may be indispensable, we believe it is necessary to launch more projects like the one presented in this article. The current situation may have made patients and providers more aware of the need to introduce initiatives of this kind and may be a unique opportunity to do so. The balance between in-person and virtual health care services will be established based on patient needs, seeking to develop a more personalised approach to medical care from this perspective. It is necessary for the competent authorities to develop the legal foundations for these consultations6 and for professionals to develop methods to analyse the quality, safety and cost-effectiveness of this care modality.

FundingThis project did not receive full or partial funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank Javier Blasco Alonso, María Juliana Serrano Nieto, María Pilar Ortiz Pérez and Antonio Vázquez Luque, the professionals that contributed to launching this project.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Masot R, Torcuato Rubio E, Núñez Cuadros E, Navas-López VM, Urda Cardona AL. Puesta en marcha de una consulta virtual de gastroenterología pediátrica antes de la epidemia por COVID-19: Un proyecto piloto pionero. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;94:331–333.