Refractory epilepsy (RE) is defined as epilepsy with poor seizure control despite treatment with anticonvulsant medication. It accounts for 25%–30% of epilepsy cases, and poses a significant therapeutic challenge from a medical perspective.1–6 One of the effective therapeutic alternatives for RE is the ketogenic diet (KD).1–6 The KD consists of a diet rich in fat and low in protein and carbohydrate aimed at increasing the levels of ketone bodies.1–6 Several theories have been proposed to explain its mechanism of action, none of them conclusive.1–3,6

Despite the popularity the diet has achieved in the past twenty years, there is still no consensus on how the KD must be managed to achieve maximum efficacy with minimum side effects and to make its use more widespread.2

The aim of our study was to assess the clinical efficacy, tolerability, degree of parental satisfaction and side effects of patients with RE treated with the KD.

We conducted a descriptive retrospective analysis of epileptic patients treated with a KD in our hospital in the past three years.

We evaluated the efficacy of the KD based on the percent reduction in the frequency of seizures (>75%, 74%–50%, <50%, and no response). We considered that patients had a good response when they experienced a seizure reduction of 50% or more compared to baseline.

We assessed parental satisfaction by means of a survey, asking their level of satisfaction (poor, fair, good, excellent).

We included a total of seven patients (six male and one female).

The onset of epilepsy occurred before age 6 months in all patients except patients 5 and 6, who had onsets at around 4 years of age.

The aetiology was genetic in five patients: two had Dravet syndrome (patients 1 and 2), one had Rett syndrome (patient 3), one a SCN2A mutation (patient 4) and one a 15q13.3 microduplication (patient 5). Two patients had lesional epilepsy, caused by a perinatal thalamic infarction in one (patient 6) and extensive malformation of cortical development involving both hemispheres in the other (patient 7).

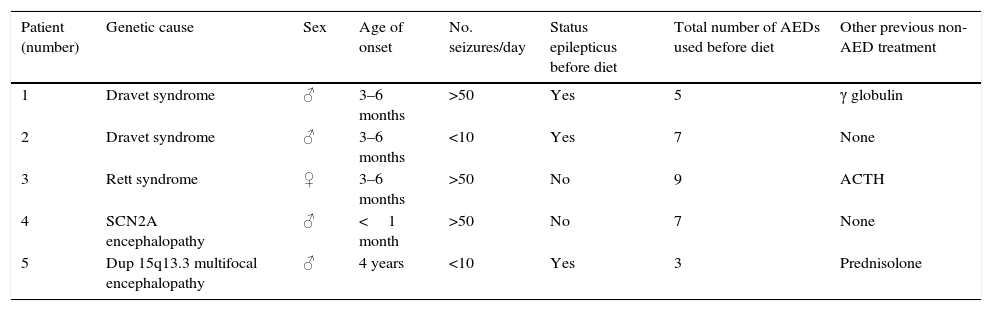

All patients had received appropriate treatment with several antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and shown no response prior to the introduction of the KD (3–5 AEDs [43%], 6–8 AEDs [43%] and >9 AEDs [14%]; Table 1).

Characteristics of the patients under study.

| Patient (number) | Genetic cause | Sex | Age of onset | No. seizures/day | Status epilepticus before diet | Total number of AEDs used before diet | Other previous non-AED treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dravet syndrome | ♂ | 3–6 months | >50 | Yes | 5 | γ globulin |

| 2 | Dravet syndrome | ♂ | 3–6 months | <10 | Yes | 7 | None |

| 3 | Rett syndrome | ♀ | 3–6 months | >50 | No | 9 | ACTH |

| 4 | SCN2A encephalopathy | ♂ | <1 month | >50 | No | 7 | None |

| 5 | Dup 15q13.3 multifocal encephalopathy | ♂ | 4 years | <10 | Yes | 3 | Prednisolone |

| Patient (number) | Structural cause | Sex | Age of onset | No. seizures/day | Status epilepticus before diet | Total number of AEDs used before diet | Other previous non-AED treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Thalamic infarction | ♂ | 4 years | 20–50 | No | 7 | γ globulin |

| 7 | Extensive malformation of cortical development in both hemispheres | ♂ | 3–6 months | 20–50 | No | 5 | ACTH |

♂, male; ♀, female; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; Dup, duplication; AED, antiepileptic drug.

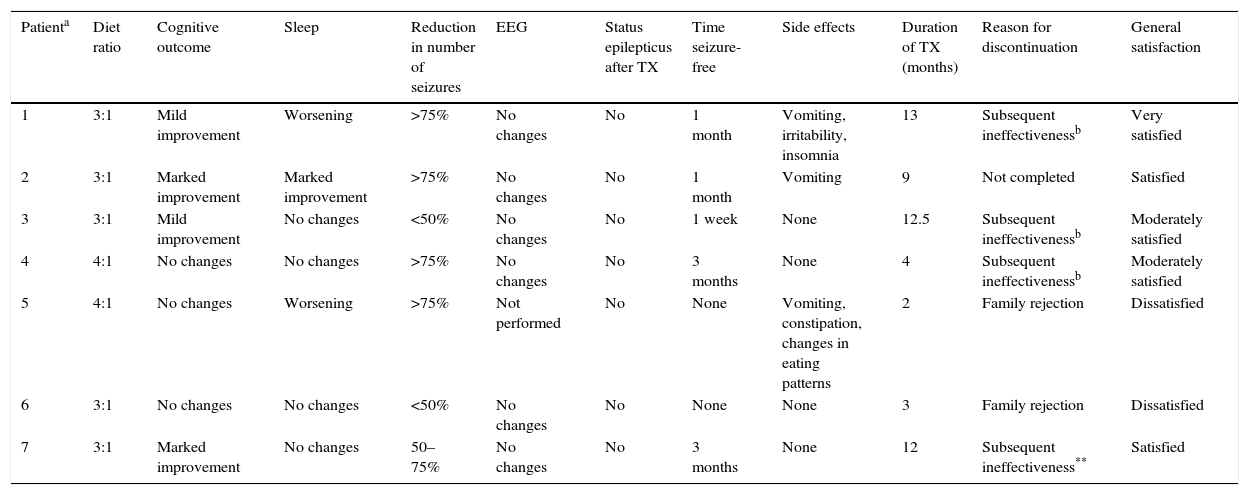

The patients that showed the best response, with a 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency, suffered from various genetic anomalies (two had Dravet syndrome, one a mutation in the SCN2A gene, and one a 15q13.3 microduplication). The patients that had the worst outcomes, remaining seizure-free for less than one week, suffered from Rett syndrome and bilateral thalamic infarction.

Patients who had a past history of status epilepticus (28.56%) did not experience it again after the introduction of the diet. Status epilepticus was also not documented in patients that had not experienced it before.

The overall degree of satisfaction of the families was good. The reason for discontinuing the diet was family choice in two patients and progressive ineffectiveness despite an initial good response in the others.

The most frequently observed side effects were vomiting (42.85%) and insomnia. However, four patients (three of them with a 3:1 diet ratio) did not experience any adverse effects (Table 2).

Summary of study outcomes.

| Patienta | Diet ratio | Cognitive outcome | Sleep | Reduction in number of seizures | EEG | Status epilepticus after TX | Time seizure-free | Side effects | Duration of TX (months) | Reason for discontinuation | General satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3:1 | Mild improvement | Worsening | >75% | No changes | No | 1 month | Vomiting, irritability, insomnia | 13 | Subsequent ineffectivenessb | Very satisfied |

| 2 | 3:1 | Marked improvement | Marked improvement | >75% | No changes | No | 1 month | Vomiting | 9 | Not completed | Satisfied |

| 3 | 3:1 | Mild improvement | No changes | <50% | No changes | No | 1 week | None | 12.5 | Subsequent ineffectivenessb | Moderately satisfied |

| 4 | 4:1 | No changes | No changes | >75% | No changes | No | 3 months | None | 4 | Subsequent ineffectivenessb | Moderately satisfied |

| 5 | 4:1 | No changes | Worsening | >75% | Not performed | No | None | Vomiting, constipation, changes in eating patterns | 2 | Family rejection | Dissatisfied |

| 6 | 3:1 | No changes | No changes | <50% | No changes | No | None | None | 3 | Family rejection | Dissatisfied |

| 7 | 3:1 | Marked improvement | No changes | 50–75% | No changes | No | 3 months | None | 12 | Subsequent ineffectiveness** | Satisfied |

EEG, electroencephalogram; TX, treatment.

The KD is effective for treatment of refractory epilepsy, although its effects are only temporary in most patients; out of the seven patients presented here, only one continues with the ketogenic diet, and the effectiveness was temporary after an initial reduction of 50% in more than 70% of patients.1–6 Patients with genetic mutations benefited most from the diet, especially patients with Dravet syndrome, who achieved a reduction in seizures of 75% or greater.2,4–6

Patients in whom the KD was introduced earlier and after trying fewer AEDs responded better than patients in whom the diet was introduced several years after the onset of epilepsy and after trying multiple antiepileptic drugs (>6 AEDs).

The side effects were similar to those described in the literature,2,6 with vomiting being the most frequent complication.6 None of the side effects led to discontinuation of the diet.2 We found fewer side effects in association with the 3:1 diet ratio.

Although this is a retrospective study with a small sample, we can conclude that the KD is efficacious for the treatment of RE. However, more randomised studies are needed to improve its implementation and prevent complications.

We want to thank our patients, who motivate us day after day. For their smiles.

Please cite this article as: Gorria Redondo N, Angulo García ML, Montesclaros Hortigüela Saeta M, Conejo Moreno D. Dieta cetogénica como opción terapéutica en la epilepsia refractaria. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;84:341–343.