The increased frequency of accidents and terrorist attacks with large numbers of casualties has spurred a growing interest on the subject of disasters.1 A catastrophe, disaster or mass-casualty incident is a situation or event that overwhelms local response resources, generates a significant number of victims and may also damage existing infrastructures.2–4 To be able to respond quickly and effectively to these events, health care facilities must have previously developed and established consensus-based protocols gathered in disaster preparedness plans. In these plans, emergency services tend to play a prominent role, as they are the setting where victims first receive care in hospital.2,4

For this reason, in 2010 the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, SEUP) formed the Working Group on Disasters and Mass Casualty Incidents with the aim of analysing the disaster preparedness plans of paediatric emergency departments (PEDs) in Spain and develop recommendations on the subject. The group carried out a pilot study in 2011 that revealed that PEDs were ill prepared to face a disaster.5 In the years that followed, the group developed a guideline for the development of disaster plans in the field of paediatrics,6 published in 2017 and distributed to every attendee to the Annual Meeting of the SEUP held in Santander, Spain, in May 2017.

At the same time, the working group developed another study with 2 objectives: (1) to describe the current situation on disaster planning in Spanish PEDs and (2) to assess the impact of the published guideline on PED preparedness.

We conducted a multicentre observational study by means of a survey. We sent a questionnaire (in Googledocs® format) to the individuals in charge of 89 PEDs affiliated to the SEUP at 2 time points: in 2016, before publication of the guideline (period 1), and in 2018, after its publication (period 2). Through this questionnaire, we collected data on hospitals, information about their disaster response plans (contents, diffusion and training of PED staff, performance of drills). We assessed the current situation of disaster response planning by analysing the responses obtained for period 2, and when it came to assessing the impact of the dissemination of the guideline, we only included the hospitals that had submitted responses for both periods in the analysis.

We received 22 responses in period 1 (response rate of 24.7%) and 25 in period 2 (response rate, 28.1%). Sixteen hospitals participated in both periods. Eighteen hospitals had external disaster response plans in period 1 and 19 had them in period 2.

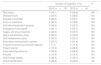

The complexity level of the care offered by participating hospitals was complex in 15, intermediate in 8 and basic/standard in 2. Sixteen were trauma centres. In the past 5 years, 8 had managed patients from mass casualty incidents (traffic accidents, fires, chlorine poisoning, terrorist attack). Nineteen hospitals had disaster response plans; 6 of them specific paediatric disaster plans and 13 general disaster plans (of which 8 had general plans contemplating the specific needs of children). In 11 cases, the plans were more than 5 years old. Fifteen hospitals reported never performing drills. According to the individuals responding to the survey, the plan was known by the staff in 8 of the hospitals. Some type for training on the subject was also performed in 8 hospitals. Table 1 summarises the contents of the disaster plans in place in period 2.

Contents of disaster response plans of paediatric emergency departments in 2018 (n=19).

| Number of hospitals, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Risk maps | 13 (68.4) |

| Disaster levels | 15 (78.9) |

| Disaster Committee | 18 (94.7) |

| Chain of command | 19 (100) |

| Activation/deactivation protocol | 18 (94.7) |

| Emergency trunk bag/kit | 13 (68.4) |

| Supply and drug checklists | 9 (47.4) |

| Space redistribution plans | 19 (100) |

| Staff redistribution plans | 18 (94.7) |

| Alternative communication system | 13 (68.4) |

| Protocol for procuring external materials | 7 (36.8) |

| Patient referral | 11 (44.0) |

| Early discharge protocol | 14 (73.7) |

| Security | 10 (52.6) |

| Victim triage system | 17 (89.5) |

| Victim identification | 19 (100) |

Of the 16 hospitals that participated in the 2 periods, 13 already had a disaster plan before the guideline was published, 1 hospital developed a plan in period 2, and 2 hospitals had no plan in either period. After the publication of the guideline, 7 of the hospitals modified their disaster plans (6 updated the existing plan and 1 developed a new plan). Among the improvements in the disaster plans, hospitals added protocols for referral of patients to other facilities, lists of necessary materials and drugs, protocols for the acquisition of materials, emergency kits and risk maps (Table 2).

Changes in disaster plan contents between the 2 periods.

| Number of hospitals, n (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 (n=13) | 2018 (n=14) | ||

| Risk maps | 3 (23.1) | 4 (28.6) | NS |

| Disaster levels | 4 (30.8) | 4 (28.6) | NS |

| Disaster Committee | 5 (38.5) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Chain of command | 6 (46.2) | 6 (42.9) | NS |

| Activation/deactivation protocol | 5 (38.5) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Emergency trunk bag/kit | 3 (23.1) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Supply and drug checklists | 4 (30.8) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Space redistribution plans | 6 (46.2) | 6 (42.9) | NS |

| Staff redistribution plans | 5 (38.5) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Alternative communication system | 3 (23.1) | 3 (21.4) | NS |

| Protocol for procuring external materials | 1 (7.7) | 2 (14.3) | NS |

| Patient referral | 2 (15.4) | 4 (28.6) | NS |

| Early discharge protocol | 4 (30.8) | 4 (28.6) | NS |

| Security | 2 (15.4) | 2 (14.3) | NS |

| Victim triage system | 5 (38.5) | 5 (35.7) | NS |

| Victim identification | 6 (46.2) | 6 (42.9) | NS |

NS, not significant.

Based on our findings, most participating PEDs have disaster plans, but few of them are known to the health care staff and most are not appropriately up to date. In this regard, it is important to underscore that having a written plan does not equate to being ready for a disaster, and it may even generate a false feeling of being prepared when this is not the case.6 Although it seems that the published guideline has achieved a small improvement on disaster planning in PEDs, it is difficult to tell whether this improvement is not due to other factors such as the terrorist attacks that happened in Barcelona and Cambrils in August 2017. Thus, other improvement strategies need to be developed involving the health care authorities and also promoting training of health care staff.5,6

David Andina Martínez, Eva Botifoll García, Nuria Clerigué Arrieta, Agustín de la Peña Garrido, Marta Bueno Barriocanal, Nuria Gilabert Iriondo, Gloria Guerrero Márquez, Maribel Lázaro Carreño, Abel Martínez Mejías, Conchita Miguez Navarro, Ana Muñoz Lozon, M. Ángeles Murillo Pozo, Cristina Parra Cotanda, Adrián Ranera Malga, Mónica Rebordosa Martínez, Rocío Rodrigo García, Agustín Rodríguez Ortiz, Eva Rupérez García, Carmen Solano Navarro.

Appendix A lists the members of the Working Group on Disasters and Mass Casualty Incidents of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (SEUP).

Please cite this article as: Parra Cotanda C, Rodrigo García R, Trenchs Sainz de la Maza V, González Peris S, Luaces Cubells C, en representación del Grupo de Trabajo de Catástrofes e Incidentes con Múltiples Víctimas de la Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (SEUP). Impacto de una guía para la elaboración de un plan de catástrofes externas en los servicios de urgencias pediátricos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;92:367–369.

Previous presentation: This study was presented as an oral communication at the XXIV Annual Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría; May 9–11, 2019; Murcia, Spain.