Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a rare benign liver neoplasm that accounts for 8% of liver tumours in adults and less than 2% in children,1,2 although some authors report that its incidence has increased in the past five years. It is more prevalent in females (66% in the paediatric age group and 90% in adulthood) and in women of fertile age with a history of oral contraceptive use, although this association has yet to be confirmed.3

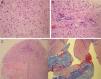

We present four cases of FNH in children aged 3–13 years diagnosed in our hospital, which are summarised in Table 1 (Fig. 1).

Description of the four clinical cases.

| Case | Age (years) | Clinical manifestations | Examination | CBCLiver function | AFP | Ultrasound | Abdominal MRI | Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | Abdominal pain | N | N | N | Hyperechoic lesion in right liver lobe measuring 8cm×6cm | Focal lesion in eighth segment, subcapsular, measuring 9cm×9.6cm×8.6cm in diameter, with a central scar, the lesion takes up contrast in the arterial phase and becomes isointense with the liver parenchyma in the portal venous phase; the central scar is hyperintense in T2 and hypointense in T1, delayed enhancement after administration of contrast | FNH |

| 2 | 5 | Abdominal pain | Hard mass in left hypochondrium, moderate pain on palpation | N | N | Solid lesion with polylobulated margins, slightly hyperechoic in right lobe of liver, with no central scar | Single lobulated mass in sixth liver segment with intralesional vessels, non-infiltrating, measuring 7cm×4cm×7cm. With contrast: rapid enhancement in the arterial phase with washout in the portal venous and delayed phases | FNH (Fig. 1) |

| 3 | 6 | Abdominal pain. Suspected appendicitis | N | N | N | Mass in subcapsular region of left lobe of liver, isoechoic, with peripheral and intralesional vascularisation. Elongated and tortuous appendix with hyperechoic adjacent mesoappendix that appeared normal in the next ultrasound checkup | Lesion in second segment of left lobe of liver, lobulated and with a well defined contour, measuring 2.8cm×4.8cm×3.6cm, nearly isoechoic with liver parenchyma. Isointense with the liver parenchyma after administration of contrast | FNH |

| 4 | 3 | Intermittent fever | N | N | N | Solid mass in segment IVb of the liver measuring 2.8cm×3.4cm×3.5cm, homogeneous and nearly isoechoic relative to the liver parenchyma, with tumour vascularisation with a particularly prominent central vessel and a normal arterial pattern | Not performed | FNH |

AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; FNH, focal nodular hyperplasia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; N, normal.

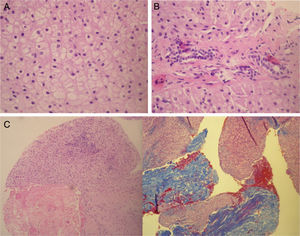

Histology of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Liver biopsy corresponding to a case of FNH: (A) normal cellularity without atypia. (B) Absence of portal triads (characteristic of FNH). Presence of bile canaliculi (inconsistent with hepatic adenoma). (C) Presence of fibrosis (Masson's trichrome stain).

It is widely believed that the pathogenic mechanism may be related to a hyperplastic response of hepatocytes to haemodynamic disturbances caused by local (vascular abnormalities or local venous thrombosis) or systemic factors (oral contraceptives and angiogenic molecules).4 Cases of FNH have also been described in children that have received chemotherapy, in whom the development of FNH may be related to the vascular damage caused by this treatment, especially in patients that have undergone haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

The disease is usually asymptomatic, and it most commonly presents as a palpable abdominal mass or hepatomegaly found by chance or by an imaging test performed for a different reason. It occasionally presents with abdominal pain. In our series, three patients presented with self-limiting abdominal pain (spontaneous resolution), and a palpable mass was found only in case 2. In case 4, we did not find an association between the clinical manifestations and FNH, so we considered it a chance finding.

In typical cases, liver function is not impaired and alpha-foetoprotein levels are normal. Imaging tests may yield findings that guide the diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown the highest sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of FNH.5 The characteristic radiological findings are: solid mass, homogeneous, with well-defined margins, lobulated and vascularised in ultrasound imaging; in MRI, the lesion is isointense or hypointense compared to the rest of the liver parenchyma in T1-weighted sequences, and hyperintense or isointense in T2-weighted sequences, with rapid contrast uptake after infusion of gadolinium due to arterial inflow. The fibrous central scar is a typical feature but it is not constant (present in 30–60% of cases, depending on the study). None of these findings is pathognomonic. The most frequent localisation is the right hepatic lobe (only found in one of the cases in our series). Most cases have solitary lesions, but up to 8% may present with multiple nodules.2

Hepatocytes appear benign on histological examination; they are arranged in rope-like structures separated by fibrous septa with multiple arterial branches radiating from a large central artery. There are atypical forms of FNH, such as telangiectatic FNH, in which there is no nodular architecture and the lesion is not structured around a vascular malformation; it is usually larger in size and associated with more frequent complications, producing symptoms and on occasion even abnormal laboratory findings.

In most cases, FNH remains stable over time, although the literature has reported cases in which the tumour decreased in size or even spontaneously regressed.3 There have been no reports of malignisation. Molecular biology studies have been conducted that confirmed that FNH is not a preneoplastic disease, and to date, no study has found somatic mutations in the β-catenin gene or other genes involved in hepatocellular adenoma, in which malignant transformation may occur.6

The rarity of cases of FNH compared to other types of liver tumours, especially malignant ones, limits the power of the evidence provided by imaging tests, so a biopsy is needed in almost every case to make a definitive diagnosis.1

Although there is no conclusive evidence to prove the advantages of observation over resection, the former approach has been adopted in the management of adults with good results. Since FNH is a benign lesion, it is better to avoid surgery whenever possible, making decisions on a case-by-case basis. The current indications for surgery are clear: presence of symptoms, increasing size of mass, or inability to rule out malignancy with certainty. Some authors propose selective embolisation as an alternative approach.3

A conservative approach with clinical and radiological followup was chosen for all cases in our series following histological diagnosis. At 70, 37, 33 and 19 months of followup, respectively, patients remained asymptomatic and the lesions stable in imaging tests.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Medinilla EE, Escobosa Sánchez O, García Hidalgo L, Acha García T. Hiperplasia nodular focal: diagnóstico a considerar ante una masa hepática. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:347–349.