Early Intervention (EI), as a paediatric service, has the duty of quantifying the results and the quality of its services provided. The accessibility of valid and reliable tools allows professionals to evaluate the quality of these services.

Main objectiveThe aim of this study is to review the scientific literature on tools used to measure the methodological and service quality in EI.

MethodsA search was made in different databases: Medline (from PubMed), Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Scopus, ERIC and Scielo. The methodological quality of the studies was tested using the COSMIN scale.

ResultsA total of 13 manuscripts met the criteria to be included in this review. Ten of them received a “good” or “reasonable” score based on the COSMIN scale.

ConclusionsDespite its importance, there is no consensus among authors on the measurement of service quality in EI. It is often the family of the children attended in EI that are considered the target to study, although the opinion of professionals carries more weight and completes the information.

La Atención Temprana (AT), como servicio pediátrico, obliga a cuantificar resultados de intervención y calidad de servicio ofrecido. La disposición de instrumentos de medida válidos y fiables permitirá a los profesionales evaluar la calidad de estos servicios.

Objetivo principalRevisar la literatura científica, analizar la calidad metodológica de las herramientas utilizadas en AT para la medición de la calidad de servicio.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda en diferentes bases de datos: Medline (a través de Pubmed), Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Scopus, ERIC y Scielo. La calidad metodológica de los estudios identificados se evaluó a través de la escala Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement (COSMIN).

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 13 artículos que cumplieron los criterios de inclusión, de los cuales 10 obtuvieron una puntuación «buena» o «razonable» según la escala COSMIN.

ConclusionesPese a su importancia, aún no existe consenso entre los autores sobre la medición de la calidad de servicio en AT. Habitualmente, es la familia de los niños atendidos en AT la población sobre la que se realizan los estudios, aunque la perspectiva de los profesionales toma auge y completa la información.

Early Intervention (EI) refers to the set of interventions targeting the paediatric population, their families and the environment with the main purpose of addressing the needs of children with or at risk of developmental disorders.1 In recent years, there have been numerous changes and advances in EI, including the development of programmes for the prevention, detection and treatment of all types of developmental disorders and the education of affected children and their families,2 which calls for the evaluation of not only their outcomes, but also of the quality of the services provided.3

The interest in service quality started in the corporate world. Today, quality does not only concern managers that wish to cut costs or assess performance, but also researchers specialised in the health care field.4

Service quality is understood as the balance of satisfaction and expectations in the mutual relationship between customers and the organisation addressing their needs.5 Quantifying service quality is a complex task, and different strategies have been formulated to facilitate its measurement, including the one proposed by Berry et al.6 based on 5 global dimensions: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy.

Despite the substantial number of studies published in recent decades and the recommendations given by public institutions,7,8 there is still no consensus on to assess service quality. The availability of measurement tools composed of key dimensions of proven validity has made it possible to estimate the quality of offered services. In addition to allowing comparison with similar services, such assessments also allow the correction of detected errors and the development of different strategies to increase customer satisfaction.9–11

When it comes to services for children, the gold standard currently used in Spain is the European Foundation for Quality Model (EFQM), designed by the European Union to promote quality improvement. As of this writing, this model is only adapted to the management of corporate settings, neglecting many important aspects that are inherent to EI services.12,13

Service quality is often confused with customer satisfaction.14 There is no consensus regarding the similarities or differences in these two concepts, as satisfaction is described as the expectations a client has of a service and how they diverge from the actual service.15 However, both are recognised as key factors for the interpretation of consumer preferences for specific services.16

Parasuraman et al.17 were pioneers in researching service quality in the health care field, designing the first scale capable of measuring the quality perceived by users: SERVQUAL. This scale has been applied in the health care field with contradictory results.18

Other authors, such as Mesa-Selmo,19 Torres Moraga and Lastra Torres10 and Romero-Galisteo et al.,20 have started to investigate and develop new scales to measure service quality in health care facilities, adapting them to the specific qualities of these settings. This broad range of possibilities suggests that while it is possible to assess service quality in different fields using a universal questionnaire as reference, the optimal approach is to use assessment tools specific for each type of setting.

We ought to highlight the importance of assessing how parents perceive the services received, given their relevance in paediatric services, as it is they that determine their quality.21

The main aim of our study was to search the scientific literature to identify the tools used for service quality assessment in EI. A secondary objective was to assess the methodological quality of the studies identified in the search.

MethodsWe performed a systematic review of the literature for articles on the measurement tools currently available to assess service quality in EI. We established criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of articles in the initial literature search and to assess the psychometric properties of the selected tools.

We carried out this review following the recommendations of the PRISMA statement.22 We registered the review in the PROSPERO database as file CRD42017077151.

Database searchTwo reviewers (IJ and RR) independently performed an exhaustive research during May 2017 in several databases: MEDLINE (through PubMed), Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Scopus, ERIC and Scielo. Some articles were added following manual searches of other sources, which allowed us to identify a larger number of works using any type of tool to assess the quality of EI services.

To identify as many tools as possible and their different versions, we did not restrict the search to a specific time interval. The descriptors used in the search were quality of service, early intervention and evaluation, using the search strategy “ab (quality of service) AND ab (evaluation) AND ab (early intervention)” adapted to the search systems of each of the different databases.

Inclusion/exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria were: study published at any time that involved at least one tool for measuring service quality in the EI field, with participation of family members/carers or EI professionals, in English or Spanish. We excluded editorials, doctoral dissertations, opinion articles and articles that did not use a rigorous methodology.

Study selectionTo ensure that the results of the review fulfilled the objectives of our study, 2 blinded researchers (IJ and RR) independently selected the articles to be included from the total identified in the literature search.

The selection was carried out in several stages. The initial stage involved the development of a database of all articles identified in the search, eliminating duplicates. This was followed by critical reading of the contents of the articles entered in this database. We saved the selected sources in the MENDELEY reference manager. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved with the help of a third reviewer (NM) with 23 years of experience in EI, ultimately achieving a level of agreement corresponding to a Cohen kappa of 1.

Similarly, we agreed to include all service quality assessment tools, including both questionnaires and interviews used in the field of EI. We did not exclude tools that assessed service quality in the context of specific disorders as long as it concerned a disorder susceptible of EI.

Data extractionTwo authors (IJ and RR) assessed the methodological quality of the studies independently by means of the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement (COSMIN) checklist. The COSMIN checklist23 can be used to evaluate the methodological quality of studies that assess the psychometric properties of health-related measurement parameters. Once again, disagreements between reviewers were resolved by a consensus process with the help of a third author (NM).

For each of the selected articles, we collected the following information: name of the instrument used, population under study, characteristics of the instrument and conclusions of the study.

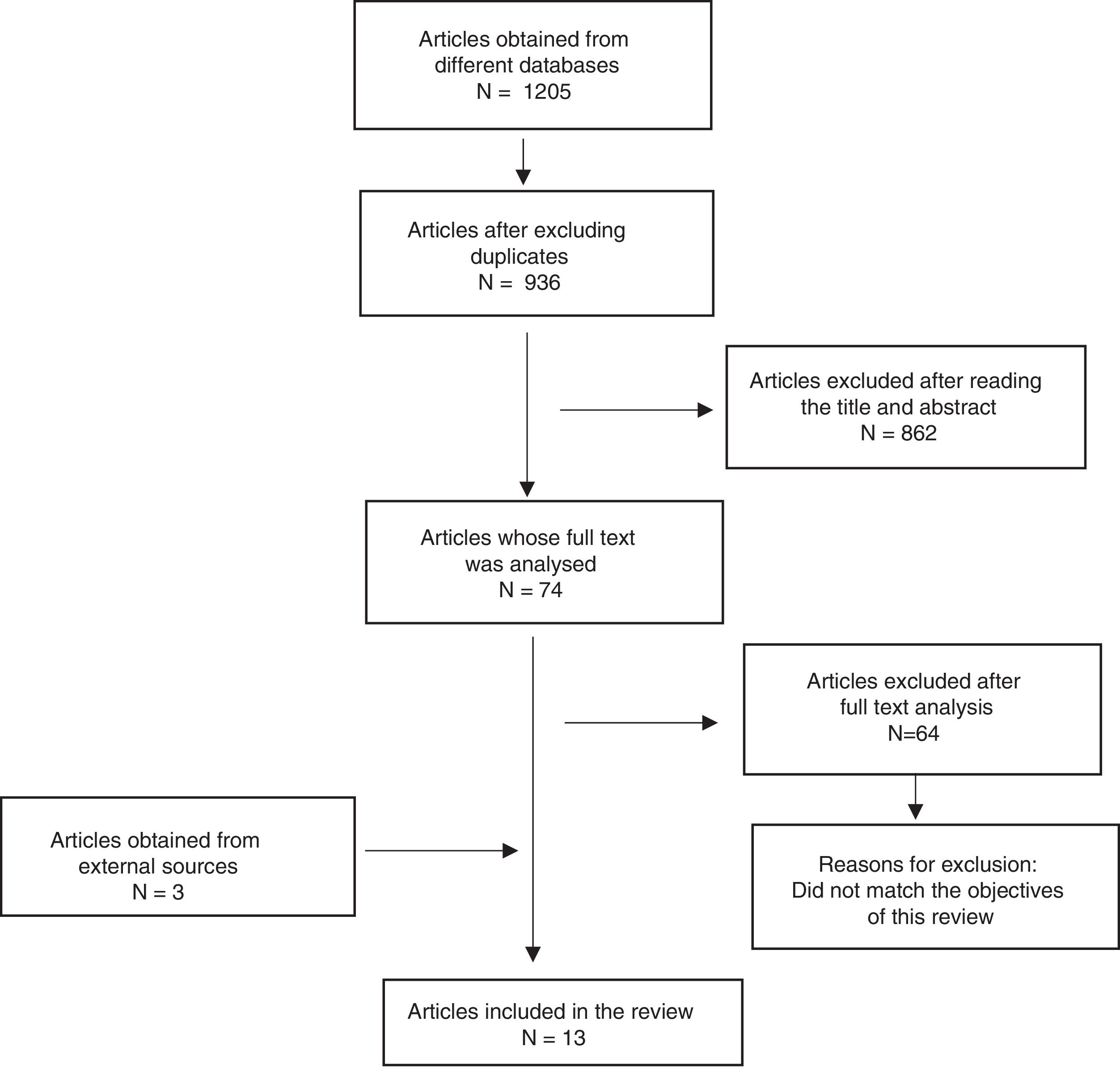

ResultsWe identified a total of 1205 articles in the different databases. Of these, 269 were excluded as duplicates, and 862 because they were not related to the subject under study. A review of the abstracts of the remaining studies led to exclusion of another 39. After a critical reading of the full text of the remaining articles, another 25 were discarded, leaving a total of 10 studies, to which we added another 3 obtained from external sources (Fig. 1).

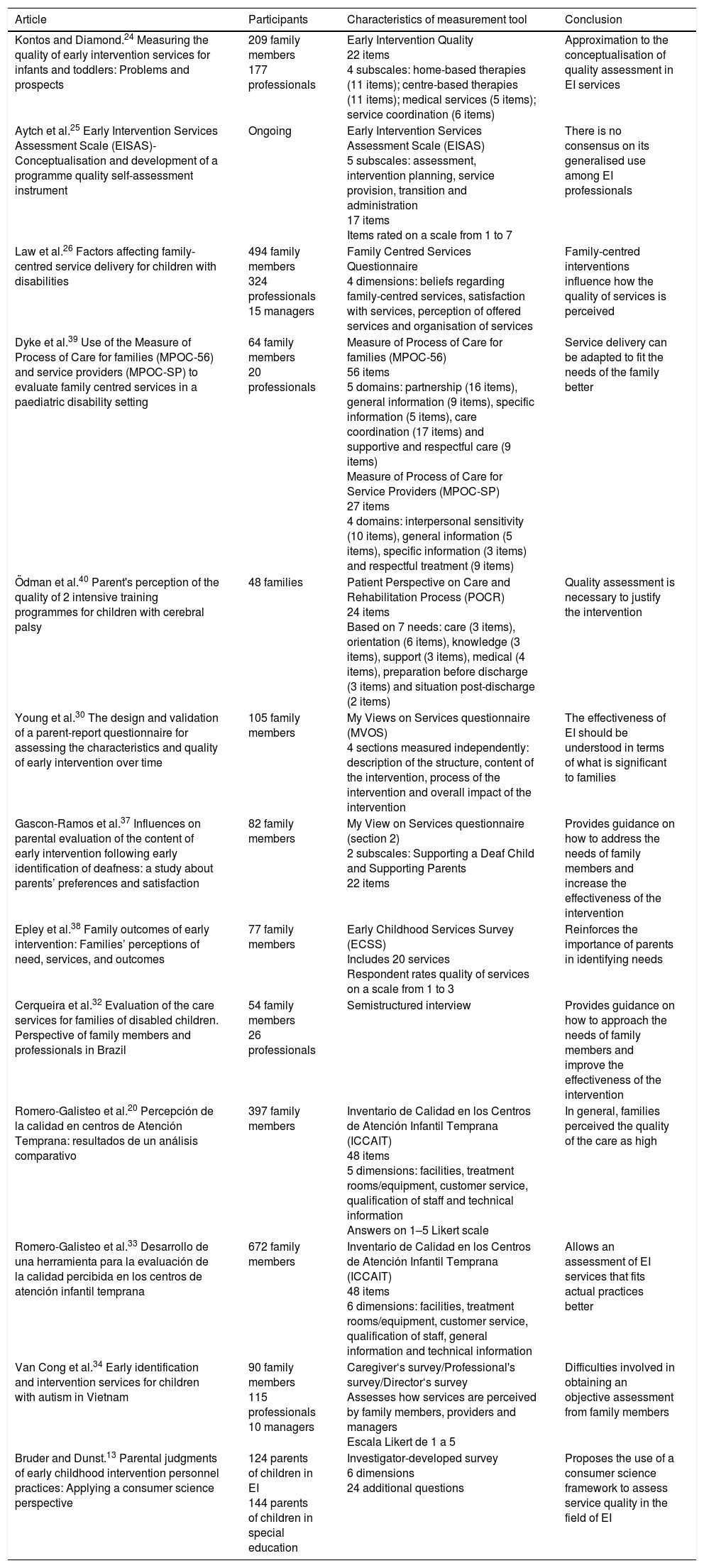

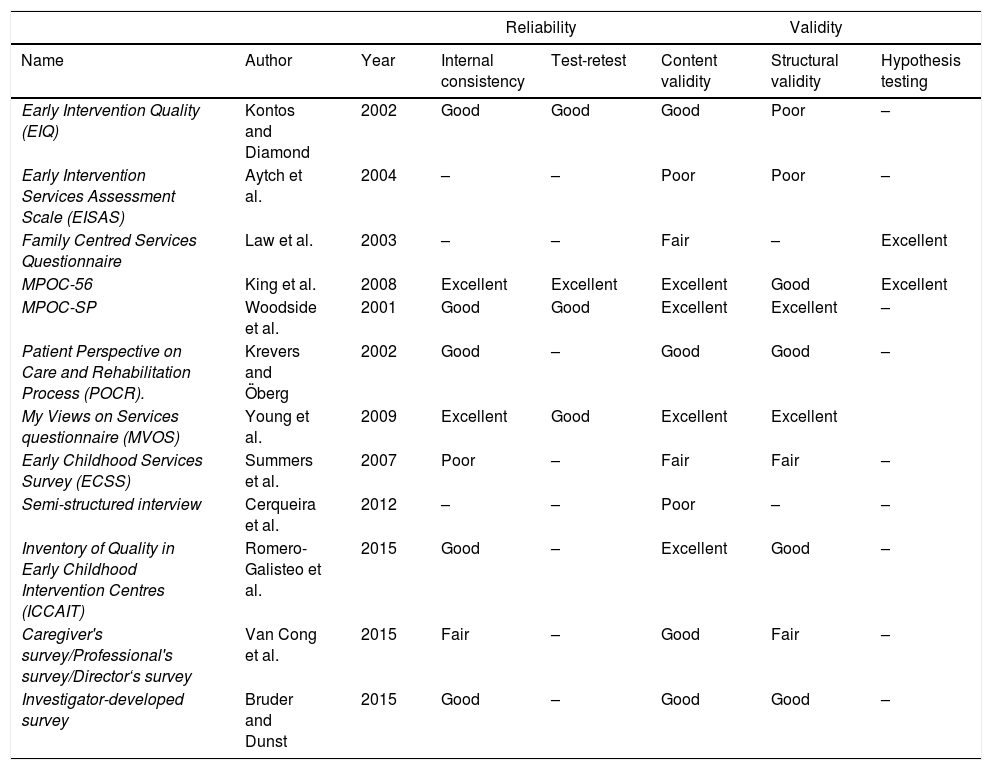

These 13 articles were the ones assessed applying the quality criteria that we had previously agreed on. We decided that the review would only include those instruments with psychometric properties that indicated adequate validity and reliability (Table 1). We assessed the methodological quality of the studies by means of the COSMIN checklist23 (Table 2). We now proceed to describe the characteristics of each of the selected tools.

Results of the review. Source: table made by the authors.

| Article | Participants | Characteristics of measurement tool | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kontos and Diamond.24 Measuring the quality of early intervention services for infants and toddlers: Problems and prospects | 209 family members 177 professionals | Early Intervention Quality 22 items 4 subscales: home-based therapies (11 items); centre-based therapies (11 items); medical services (5 items); service coordination (6 items) | Approximation to the conceptualisation of quality assessment in EI services |

| Aytch et al.25 Early Intervention Services Assessment Scale (EISAS)-Conceptualisation and development of a programme quality self-assessment instrument | Ongoing | Early Intervention Services Assessment Scale (EISAS) 5 subscales: assessment, intervention planning, service provision, transition and administration 17 items Items rated on a scale from 1 to 7 | There is no consensus on its generalised use among EI professionals |

| Law et al.26 Factors affecting family-centred service delivery for children with disabilities | 494 family members 324 professionals 15 managers | Family Centred Services Questionnaire 4 dimensions: beliefs regarding family-centred services, satisfaction with services, perception of offered services and organisation of services | Family-centred interventions influence how the quality of services is perceived |

| Dyke et al.39 Use of the Measure of Process of Care for families (MPOC-56) and service providers (MPOC-SP) to evaluate family centred services in a paediatric disability setting | 64 family members 20 professionals | Measure of Process of Care for families (MPOC-56) 56 items 5 domains: partnership (16 items), general information (9 items), specific information (5 items), care coordination (17 items) and supportive and respectful care (9 items) Measure of Process of Care for Service Providers (MPOC-SP) 27 items 4 domains: interpersonal sensitivity (10 items), general information (5 items), specific information (3 items) and respectful treatment (9 items) | Service delivery can be adapted to fit the needs of the family better |

| Ödman et al.40 Parent's perception of the quality of 2 intensive training programmes for children with cerebral palsy | 48 families | Patient Perspective on Care and Rehabilitation Process (POCR) 24 items Based on 7 needs: care (3 items), orientation (6 items), knowledge (3 items), support (3 items), medical (4 items), preparation before discharge (3 items) and situation post-discharge (2 items) | Quality assessment is necessary to justify the intervention |

| Young et al.30 The design and validation of a parent-report questionnaire for assessing the characteristics and quality of early intervention over time | 105 family members | My Views on Services questionnaire (MVOS) 4 sections measured independently: description of the structure, content of the intervention, process of the intervention and overall impact of the intervention | The effectiveness of EI should be understood in terms of what is significant to families |

| Gascon-Ramos et al.37 Influences on parental evaluation of the content of early intervention following early identification of deafness: a study about parents’ preferences and satisfaction | 82 family members | My View on Services questionnaire (section 2) 2 subscales: Supporting a Deaf Child and Supporting Parents 22 items | Provides guidance on how to address the needs of family members and increase the effectiveness of the intervention |

| Epley et al.38 Family outcomes of early intervention: Families’ perceptions of need, services, and outcomes | 77 family members | Early Childhood Services Survey (ECSS) Includes 20 services Respondent rates quality of services on a scale from 1 to 3 | Reinforces the importance of parents in identifying needs |

| Cerqueira et al.32 Evaluation of the care services for families of disabled children. Perspective of family members and professionals in Brazil | 54 family members 26 professionals | Semistructured interview | Provides guidance on how to approach the needs of family members and improve the effectiveness of the intervention |

| Romero-Galisteo et al.20 Percepción de la calidad en centros de Atención Temprana: resultados de un análisis comparativo | 397 family members | Inventario de Calidad en los Centros de Atención Infantil Temprana (ICCAIT) 48 items 5 dimensions: facilities, treatment rooms/equipment, customer service, qualification of staff and technical information Answers on 1–5 Likert scale | In general, families perceived the quality of the care as high |

| Romero-Galisteo et al.33 Desarrollo de una herramienta para la evaluación de la calidad percibida en los centros de atención infantil temprana | 672 family members | Inventario de Calidad en los Centros de Atención Infantil Temprana (ICCAIT) 48 items 6 dimensions: facilities, treatment rooms/equipment, customer service, qualification of staff, general information and technical information | Allows an assessment of EI services that fits actual practices better |

| Van Cong et al.34 Early identification and intervention services for children with autism in Vietnam | 90 family members 115 professionals 10 managers | Caregiver‘s survey/Professional's survey/Director‘s survey Assesses how services are perceived by family members, providers and managers Escala Likert de 1 a 5 | Difficulties involved in obtaining an objective assessment from family members |

| Bruder and Dunst.13 Parental judgments of early childhood intervention personnel practices: Applying a consumer science perspective | 124 parents of children in EI 144 parents of children in special education | Investigator-developed survey 6 dimensions 24 additional questions | Proposes the use of a consumer science framework to assess service quality in the field of EI |

Ratings based on the COSMIN checklist.

| Reliability | Validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Author | Year | Internal consistency | Test-retest | Content validity | Structural validity | Hypothesis testing |

| Early Intervention Quality (EIQ) | Kontos and Diamond | 2002 | Good | Good | Good | Poor | – |

| Early Intervention Services Assessment Scale (EISAS) | Aytch et al. | 2004 | – | – | Poor | Poor | – |

| Family Centred Services Questionnaire | Law et al. | 2003 | – | – | Fair | – | Excellent |

| MPOC-56 | King et al. | 2008 | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Good | Excellent |

| MPOC-SP | Woodside et al. | 2001 | Good | Good | Excellent | Excellent | – |

| Patient Perspective on Care and Rehabilitation Process (POCR). | Krevers and Öberg | 2002 | Good | – | Good | Good | – |

| My Views on Services questionnaire (MVOS) | Young et al. | 2009 | Excellent | Good | Excellent | Excellent | |

| Early Childhood Services Survey (ECSS) | Summers et al. | 2007 | Poor | – | Fair | Fair | – |

| Semi-structured interview | Cerqueira et al. | 2012 | – | – | Poor | – | – |

| Inventory of Quality in Early Childhood Intervention Centres (ICCAIT) | Romero-Galisteo et al. | 2015 | Good | – | Excellent | Good | – |

| Caregiver's survey/Professional's survey/Director‘s survey | Van Cong et al. | 2015 | Fair | – | Good | Fair | – |

| Investigator-developed survey | Bruder and Dunst | 2015 | Good | – | Good | Good | – |

Early Intervention Quality (EIQ).24 A self-assessment scale to be completed by the family of clients of EI centres or EI programme staff. It consists of 22 items divided into 4 subscales. The first 2 subscales assess the characteristics of home-based or centre-based therapies (1 of the 2 is completed based on the type of intervention delivered), and each comprises 11 items. The third subscale (5 items) evaluates health/medical services, and the fourth subscale (6 items) the coordination of services.

Early Intervention Services Assessment Scale (EISAS).25 Scale currently under development consisting of 17 items divided into 5 subscales: assessment, intervention planning, service provision, transition and administration. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 7. This scale can be used both by families of clients and by EI professionals.

Family Centred Services Questionnaire.26 Questionnaire package to assess the quality of services delivered through 4 dimensions. The family version includes questionnaires about the child's disability, the nature of the services received, beliefs of the family regarding participation in EI, perceptions about the organisation delivering services and perceptions about the quality of the services. The version adapted to EI programme staff and managers includes items such as the number of clients served, nature of services provided, amount of information given to families, overall budget, changes implemented in the centre and perceived quality of services.

Measure of Process of Care for families (MPOC-56).27 Instrument consisting of 56 items divided in 5 domains: the first one assesses enabling and partnership with the family during the intervention (16 items); the second, the general information provided about the service (9 items); the third, the specific information given about the characteristics and progress of the child (5 items); the fourth, the quality of the coordination between the different professionals involved in care (17 items); lastly, the fifth assesses the support and respect received in the context of care (9 items). Each domain describes family-centred behaviours, and respondents are asked to rate them on a 7-point scale.

Measure of Process of Care for Service Providers (MPOC-SP).28 Version for service providers comprising 27 items divided into 4 domains: the first assesses interpersonal sensitivity (10 items); the second one, the general information given (5 items); the third one, the communication of specific information about the child (3 items); and the last one, the respectful treatment of families (9 items). All these behaviours are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 point (never) to 7 points (to a great extent). This scale is applicable to different fields.

Patient Perspective on Care and Rehabilitation Process (POCR).29 This instrument assesses patient-perceived quality of care, including health outcomes. It measures 7 dimensions: need for adequate care (3 items); need for orientation within care context (6 items); need for knowledge and control (3 items); need for support and autonomy (3 items); medical and interactional needs (4 items); need for preparedness before discharge (3 items) and situation post-discharge (2 items).

My Views on Services questionnaire (MVOS).30 Questionnaire divided into 4 sections that can be assessed independently: (1) description of the structure of services evaluated according to timeliness and availability; (2) content of intervention evaluated according to quantity, importance, and satisfaction; (3) process of intervention evaluated according to the performance of professionals and the importance of the practice, and (4) overall impact of the intervention.

My View on Services questionnaire (section 2).30 Only section 2 of the MVOS questionnaire, which consists of 22 items relating to the content of the actual intervention. These items are assessed based on the importance assigned by the responding family member on a 4-point scale. This section is itself divided into 2 subscales.

Early Childhood Services Survey (ECSS).31 Assesses how families perceive their needs in relation to the child's disability and the extent to which EI services meet those perceived needs. The ECSS includes 20 services related to disability. For each service, respondents are asked to indicate whether they consider they need the service (“yes”) or they do not (“no”). For services for which the answer was “yes”, they are asked to rate the quality of the service on a scale from 1 to 3.

Semistructured interview.32 Semistructured interview organised in 2 dimensions. The first section collects information on the family to assess sociodemographic characteristics and family functioning. The second section assesses the characteristics and perceived quality of services and the type of care offered by different institutions.

Inventario de Calidad en los Centros de Atención Infantil Temprana (Quality Inventory in Early Intervention Centres, ICCAIT).33 Self-administered questionnaire that assesses the quality of EI services as perceived by the user. It comprises 48 items with answers on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“totally disagree”) to 5 (“totally agree”), including some questions to obtain sociodemographic data. The questionnaire is structured in 5 dimensions: facilities, treatment rooms/equipment, customer service, qualification of staff and technical information.

Caregiver's survey/Professional's survey/Director's survey.34 Collection of surveys assessing how services are perceived by caregivers and by programme staff and managers.

Investigator-developed survey.13 Scale divided into 6 dimensions. It includes items on the characteristics of participants and their children, type of involvement of parents in child's EI or preschool special education programme and 24 items asking parents to evaluate the primary service provider.

DiscussionIn recent years, the involvement of the family has grown increasingly important in the EI field. Further efforts are necessary to continue to raise awareness in EI professionals of the family as a unit of intervention that can contribute opinions and participate in decision-making.21 This perspective brings forth a challenge we need to address by assessing the perceptions of family members regarding services received, the interventions practised and the changes that could be made to improve them.

One possible approach to involving families and knowing how they perceive EI is the use of tools to assess service quality. However, there is no consensus yet on how to assess service quality the EI field.35

Based on the reviewed literature, experts on the subject disagree regarding the dimensions that should be included in the assessment of service quality, as evinced by the heterogeneity of the tools presented in the articles selected in our study. Each of them assigns more or less importance to specific aspects. On one hand, it is true that each instrument or questionnaire should be adapted to the specific nature of the service that it seeks to assess and the organisational structure in which it unfolds, but on the other this variability presents disadvantages not only in EI, but also in other fields, in the comparison of results and the establishment of standardised criteria.

Despite the importance of assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of EI, there is little published evidence on performance beyond the assessment of developmental outcomes in children, with other aspects being neglected,36 which poses a potential limitation for the use of assessment scales. In our review, we found only 10 tools with good-enough psychometric properties to be considered valid and reliable,13,24,26–31,33,34 of which 3 rated poor or fair in some of the indicators of the COSMIN checklist.

On the other hand, the authors of 3 studies chose to use scales that had not been validated or questionnaires they had developed themselves without assessing their psychometric properties. Thus, Law et al.,26 used a combination of already validated scales but did not analyse the association between them, and Cerqueira et al.32 and Aytch et al.25 took as valid the results obtained using tools with internal consistency values below recommended thresholds. While these articles enhance and increase our knowledge on quality assessment in this area, they also illustrate the scarcity and poor quality of the research available on the subject. It is not possible to determine the reasons leading various researchers choose these options instead of using instruments that have already been validated.

A large proportion of the studies on assessment tools included data on psychosocial or sociocultural variables.13,20,26,30,31,33,34,37,38 The analysis of socioeconomic and demographic factors reveals that variables such as educational attainment, social status or age may impact the perception of families of the quality of services. Differences are also observed among EI professionals, although in this case the factors that have the most influence are usually educational attainment and the number of years of experience in the EI field.39

Given the characteristics of the population under study and the inability of young children to fill out any type of form, families are frequently the source used to assess service quality. Nevertheless, several studies13,24,26,32,34,39 have highlighted the importance of assessing quality from the perspective of professionals in the field, as this could enhance the information obtained from families and contribute new data. The scarcity of studies in professionals underscores the need to conduct further research from the perspective of this collective.

Last of all, the association between service quality and quality of live analysed by some authors is another interesting aspect to consider.31 This opens a new field of inquiry that expands the competencies associated with service quality, suggesting new directions for research.

When it comes to clinical implications, based on the results of our literature review, we propose including the assessment of service quality from the client's perspective13 in the overall assessment of service quality performed by agents involved in the delivery of EI services.

One of the current positive aspects in this area, based on most of the studies reviewed, is that families are now considered a reference for service quality assessment in EI, as opposed to professionals alone. However, this does not seem to be a customary practice in Spain yet. The systematic assessment of perceived service quality would enhance the wellbeing and satisfaction of users of EI services. It would also provide an objective baseline that could guide ongoing efforts to improve the management of EI centres.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jemes Campaña IC, Romero-Galisteo RP, Labajos Manzanares MT, Moreno Morales N. Evaluación de la calidad de servicio en Atención Temprana: revisión sistemática. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90:301–309.