The renewal of clinical practice guidelines on acute bronchiolitis (AB) requires the re-assessment of the consequences of their implementation. An update is presented on the main clinical and epidemiological variables in patients hospitalised due to AB in Southern Europe and an analysis is made of the causes associated with longer hospital stay.

Patients and methodA retrospective study was conducted on patients admitted to hospital due to AB during 5 epidemics (2010–2015), with an analysis of the major clinical and epidemiological variables. A logistic regression analysis was performed on the factors associated with a longer hospital stay.

ResultsThe beginning of the epidemic occurred between the 4th week of September and the 3rd week of October. Of those children under 2 years (42530), 15.21% (6468 patients) attended paediatric emergency department due to having AB, and 2.36% (1006 patients) were admitted. Of these, 18.5% were premature, 12.2% had a birth weight <2300g, 21.1% were younger than 1 month, 10.8% consulted for associated apnoea, 31.1% had an intake <50%, and 13.1% had bacterial superinfection. These factors were independently associated with prolonged stay. The median length of stay was 5 days, and 8.5% of cases were admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

ConclusionsThe beginning of the bronchiolitis epidemic showed a variability of up to 4 weeks in this region. Five years after implementing the new guidelines, the incidence of admissions was approximately 2.3%, and appeared stable compared to previous studies. The mean age of the patients decreased to 2.4 months, although with a similar proportion of PICU admissions of 8.5%.

Independent factors associated with prolonged stay were: low birth weight, age less than one month, apnoea prior-to-admission, intake of less than 50%, and severe bacterial superinfection. Respiratory bacterial infection exceeded the prevalence of urinary tract infection.

La renovación de las guías de práctica clínica sobre la bronquiolitis aguda (BA) obliga a reevaluar las consecuencias de su implantación. Pretendemos actualizar las principales variables clínico-epidemiológicas en pacientes ingresados por BA en el sur de Europa y analizar las causas de la estancia prolongada.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio retrospectivo de ingresos por BA durante 5 epidemias (2010-2015), con descripción de las principales variables clínico-epidemiológicas y análisis por regresión logística de los factores asociados a mayor estancia.

ResultadosEl inicio de la epidemia ocurrió entre las semanas cuarta de septiembre y tercera de octubre. De los menores de 2 años (42.530 niños), el 15,21% (6.468 pacientes) acudieron a urgencias por BA y el 2,36% ingresaron (1.006 pacientes), con un 18,5% de prematuros. El 12,2% tenían peso al nacimiento inferior a 2.300g. El 21,1% eran menores de un mes, consultaron por apnea asociada el 10,8%, ingesta inferior al 50% en el 31,1% y presentaban sobreinfección bacteriana el 13,1%. Estos factores se asociaron de forma independiente a la estancia prolongada. La mediana de estancia fue de 5 días y la proporción de ingresos en la unidad de cuidados intensivos pediátricos (UCIP) del 8,5% de los casos.

ConclusionesEl inicio de la epidemia de la bronquiolitis mostró una variabilidad de hasta 4 semanas en nuestro medio. Tras 5 años de la implantación de la guía de práctica clínica, la incidencia de ingresos está en torno al 2,3% y parece estable respecto a estudios previos. La edad media de los pacientes desciende a 2,4 meses, aunque con una proporción similar de ingresos en la UCIP de un 8,5%.

Los factores de riesgo independiente asociados a una estancia hospitalaria más prolongada fueron: bajo peso al nacimiento, edad menor de un mes, apneas previas al ingreso, ingesta inferior al 50% y la sobreinfección bacteriana grave, donde la infección respiratoria superó la prevalencia de infección del tracto urinario grave.

Despite the passage of time, no infectious illness—recognised from the dawn of European paediatrics1—has ever generated a greater health care burden than acute bronchiolitis (AB).2–6 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the causative agent in approximately 60%–75% of cases.6,7 As was the case in the early approaches to its management,1 there is no etiologic treatment for this disease once it is diagnosed, so it is based on symptomatic treatment and respiratory support of varying intensity, and has been revised in recent years in several clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).8–11

The possibility of vaccinating infants or pregnant women is drawing near,12 and the strategy to fight this disease requires adequate knowledge of its epidemiology based on the geographical and environmental characteristics of each region in order to carry out interventions fitting specific circumstances. The results of epidemiological studies on AB published in Europe, most of which have been conducted in hospitalised patients, are somewhat inconsistent.2,5,13–16 Updates of CPGs for the management of AB and their implementation—as was the case in our hospital—since 201011 warrant an evaluation of the results of their introduction and their impact on inpatient care delivery.

Our aim was to describe and compare key epidemiological and clinical variables in patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital in a coastal town in southern Europe during 5 recent outbreaks of AB after an updated CPG had been firmly established following its introduction in 2010.11 We analysed the incidence of hospitalisation relative to emergency department visits and the need for care at the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) level, as well as severity defined in terms of length of stay and associated factors. We also estimated the timing of the epidemic season onset and its inter-annual variability.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective study in patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital between October 1, 2010 and March 31, 2015 with a discharge diagnosis of AB defined, on the basis of the classical criteria of McConnochie, as the first episode of acute lower respiratory illness associated with a history of cold symptoms in children aged 24 months or younger.17 This women's and children's hospital is the main hospital for a health department with a catchment area of 1.2 million inhabitants including a catchment paediatric population of approximately 100000 children, of who we estimated 42530 were aged 24 months, and thus eligible for inclusion, at the beginning of the study. Its geographical location on the coast at 36°43′0″ North makes it the southernmost tertiary referral children's hospital in Europe, with a Mediterranean climate.

The medical records of our patients had uniform documentation of the most important variables, as this is a frequent illness with a standardised management. The criteria for hospital admission were those established in the aforementioned CPG.11 In our hospital, all patients were evaluated for the presence of RSV at admission with a rapid antigen detection test on nasopharyngeal aspirate samples (RSV card letitest®, Leti Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) to determine cohort membership.18 From the moment of admission, all patients underwent continuous pulse oximetry monitoring until they were completely stable in an inpatient unit specifically dedicated to infants with AB.

The researchers also reviewed the medical records of patients managed in the emergency department to determine the count and incidence of other cases with a diagnostic code of AB at discharge during the period under study. For hospitalised patients, we reviewed the electronic health records to collect demographic and clinical information. We collected data for the following variables in each patient: sex, age, month of admission, birth weight, gestational age, maternal age, postmenstrual age, multiple pregnancy, caesarean delivery, environmental and/or prenatal exposure to tobacco, breastfeeding, siblings aged less than 6 years and aged 6–14 years, history of atopy in first-degree relatives, chronic disease (personal history of heart disease, disabling neurologic disease or bronchopulmonary dysplasia), days elapsed from onset to admission, fever, degree of loss of appetite, underweight (<3rd percentile), severity at admission determined by means of a validated scale,19 presence of apnoea, length of stay (in days) in ward and in intensive care unit, and severe bacterial co-infection (confirmed or suspected). Cases of UTI and sepsis were confirmed by positive urine and/or blood culture results in association with compatible symptoms. When it came to suspected respiratory co-infection, its presence was determined based on previously described clinical and laboratory criteria,20–22 including elevation of acute phase reactants, with a concentration of more than 70mg/L for CRP and more than 0.5ng/mL for procalcitonin.

We considered that an outbreak had started when the weekly incidence of AB in the emergency department exceeded the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the baseline incidence of cases outside the epidemic season (from April to September) for two consecutive weeks, applying the classical approach of Serfling.23

We compared the behaviour of the study variables based on the presence of RSV, and analysed the risk factors for increased length of stay using the mean length of stay in days from previous studies as a reference.7 In the analysis of length of stay, we excluded patients with underlying diseases and focused on healthy patients, who constitute approximately 95% of the total in most case series.14,24,25 We performed the statistical analysis with the free software PSPP. We summarised qualitative variables as percentages and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation. We used the chi square test to study the association between quantitative variables. We used logistic regression for the multivariate analysis of factors associated to increased length of stay, including in the final model those variables for which we have obtained a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariate analysis. We defined statistical significance as a p-value of less than 0.05 in any of the hypothesis tests, and calculated all confidence intervals for a 95% confidence level.

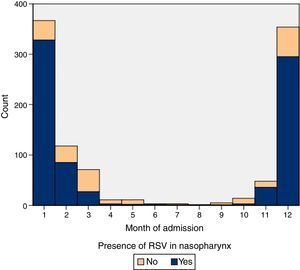

ResultsIn the period under study, 15.21% (6468 patients) of children aged less than 24 months sought care in our emergency department for AB, and 2.36% (1006 patients) were admitted to hospital. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of our sample. The baseline weekly incidence calculated for the April-to-October periods was of 5.17 cases (95% CI, 4.46–5.91). Table 2 shows the outbreak onset week for each season, determined based on the incidence rate. In our study, the differences in the timing of season onset spanned 4 weeks. Fig. 1 shows the incidence of hospitalisation by month of the year.

Quantitative variables in patients admitted with bronchiolitis included in the study (n=1006).

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Interquartile range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) | 432 | 5150 | 3053.78 | 3130 | 673.303 | 2700–3500 |

| Weeks of gestation | 25.0 | 42.0 | 38.007 | 38.5 | 2.59 | 37–40 |

| Age (months) | 0.13 | 18.14 | 2.4640 | 1.83 | 2.05 | 1.117–3.195 |

| Postmenstrual age | 34.29 | 105.86 | 48.5362 | 46.28 | 8.62 | 42.85–52.0 |

| Maternal age (years) | 15 | 48 | 29.45 | 30 | 6.06 | 25–34 |

| Total length of stay | 1 | 60 | 6.17 | 5 | 4.89 | 3–7 |

| PICU length of stay | 1 | 25 | 7.2588 | 6 | 4.82 | 4–9 |

PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

Mean cases per week of patients with bronchiolitis managed in the emergency department outside the epidemic season (April 1 through September 30), 95% confidence interval, and outbreak onset week.

| Mean cases/week | Confidence interval | Outbreak onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2011 | 5.83 | 3.63–8.04 | 1st week October |

| 2011–2012 | 5.73 | 3.81–7.65 | 1st week October |

| 2012–2013 | 4.50 | 2.91–6.09 | 1st week October |

| 2013–2014 | 5.52 | 3.31–7.73 | 4th week September |

| 2014–2015 | 4.45 | 3.19–5.70 | 3rd week October |

| Total | 5.17 | 4.46–5.91 |

Respiratory syncytial virus was detected in the aspirate specimens of 77.9% of hospitalised patients. Table 3 shows the data for the different variables based on the presence or absence of RSV with their respective frequencies (n). The mean age was 2.46 months (95% CI, 2.34–2.59); 71.8% of the patients were aged less than 3 months, 93.6% less than 6 months and only 0.5% more than 12 months. Of all patients, 53.3% were male and 81.5% had been born at more than 37 weeks gestation, 15.6% between 32 and 37 weeks gestation and 2.9% at fewer than 32 weeks. Of all pregnancies, 7.6% were multiple, and 30.8% were delivered by caesarean section. Forty percent of patients were exclusively breastfed. Also, 17.6% were exposed to tobacco prenatally and 38.6% to environmental smoke after birth. A history of atopy in first-degree relatives was found in 22.6%. Of all patients, 63.4% had siblings aged less than 6 years and 24.2% siblings aged 6–14 years. There was a personal history of heart disease, neurologic disease and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in 2.9%, 1.3% and 1.7% of patients, respectively. Respiratory syncytial virus was detected in 9 patients that received doses of palivizumab. In 53.9% of cases, patients sought care in the day of onset of respiratory problems.

Comparison of epidemiological and clinical variables in hospitalised patients with bronchiolitis based on the presence or absence of RSV using the chi square test.

| (n=1006) n | % | RSV % (n=778) | Non-RSV % (n=228) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 1006 | 0.866 | |||

| <1 | 21.1 | 21.5 | 19.8 | ||

| 1–3 | 50.6 | 50.4 | 51.4 | ||

| >3 | 28.3 | 28.1 | 28.8 | ||

| Sex | 1006 | 0.025 | |||

| Male | 53.3 | 51.4 | 59.1 | ||

| Female | 46.7 | 48.6 | 40.9 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | 944 | 0.041 | |||

| <2300 | 12.2 | 10.8 | 17.1 | ||

| 2300–3100 | 36.7 | 36.8 | 36.2 | ||

| >3100 | 51.1 | 52.4 | 46.7 | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 998 | <0.001 | |||

| ≥37 | 81.5 | 83.9 | 73.0 | ||

| 32–36 | 15.6 | 14.4 | 19.8 | ||

| <32 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 7.2 | ||

| Multiple gestation | 963 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 0.438 |

| C-section | 968 | 30.8 | 31.1 | 30.0 | 0.779 |

| Maternal age (years) | 0.009 | ||||

| <25 | 26.2 | 23.4 | 36.0 | ||

| 25–30 | 28.5 | 29.7 | 24.2 | ||

| 30–34 | 25.2 | 25.8 | 23.0 | ||

| >34 | 20.2 | 21.1 | 16.9 | ||

| Breastfeeding | 915 | 40.0 | 42.2 | 32.2 | 0.010 |

| Prenatal tobacco exposure | 924 | 17.6 | 170 | 19.7 | 0.365 |

| Environmental smoke | 925 | 38.6 | 35.7 | 48.8 | 0.001 |

| Atopy in family | 966 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 26.0 | 0.185 |

| Siblings <6 years | 865 | 63.4 | 61.8 | 68.8 | 0.068 |

| Siblings 6–14 years | 865 | 24.2 | 25.3 | 20.5 | 0.184 |

| Days since onset | 961 | 0.437 | |||

| 1 day | 54.0 | 53.1 | 57.2 | ||

| 2 days | 22.0 | 22.1 | 21.6 | ||

| 3 days | 12.3 | 13.2 | 9.1 | ||

| >3 days | 11.7 | 11.6 | 12.0 | ||

| Fever >38°C | 996 | 37.3 | 39.6 | 29.9 | 0.009 |

| SpO2<92% | 848 | 28.8 | 30.7 | 22.6 | 0.080 |

| Oral intake <50% | 31.1 | 32.2 | 26.9 | 0.156 | |

| Weight percentile <3rd | 920 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 0.096 |

| ABSS | 581 | 0.064 | |||

| Mild | 33.0 | 30.8 | 35.7 | ||

| Moderate | 62.6 | 62.4 | 62.7 | ||

| Severe | 5.4 | 6.8 | 1.6 | ||

| Apnoea prior to admission | 999 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 14.9 | 0.029 |

| Apnoea during stay | 999 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 0.738 |

| Nasogastric tube feeding | 996 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 9.5 | 0.039 |

| PICU admission | 1006 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 0.836 |

| Severe bacterial infection | 977 | 15.5 | 16.3 | 12.3 | 0.446 |

| No | 84.5 | 83.7 | 87.7 | ||

| UTI | 3.0 | 3.2 | 1.9 | ||

| Respiratory infection | 10.9 | 11.3 | 9.4 | ||

| Sepsis | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.9 | ||

| Readmission | 1006 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.223 |

ABSS, acute bronchiolitis severity scale; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SpO2, oxygen saturation; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Significant p-values presented in boldface.

In our series, 37.3% of patients presented with fever and 28.8% with oxygen saturations of less than 92% in the initial assessment. Also, there was a reduction in oral intake of more than 50% in 31.1% of cases. Eight percent presented had weights below the 3rd percentile. Based on the severity scale score at admission, we classified 62.6% of cases as moderate and 5.4% as severe. A history of apnoea prior to admission was reported in 10.8%, but only 4.9% of patients had episodes of apnoea in hospital. Nasogastric tube feeding was required in 13.9% of cases, and 8.5% required admission to the PICU (85 cases: 53 required CPAP, 21 invasive mechanical ventilation, 4 high-frequency ventilation, 7 high-flow oxygen therapy). Only 11.4% did not require oxygen therapy. Severe bacterial infections were present in 15.5% (there were three detected types: UTI, respiratory superinfection and sepsis; Table 2), of which only 1.9% were classified as nosocomial. Readmission occurred in 2.1% of cases. Two patients died, which amounted to 0.19% of hospitalised patients.

There were no significant differences between epidemic seasons in mean length of stay. Table 4 shows the results of the comparison of patients with stays longer than the median stay, which was of 5 days, and the rest of the sample. The variables that were statistically significant in the final model were age, a history of apnoea prior to admission, bacterial co-infection and reduced oral intake of less than 50% at the time of admission (Table 5).

Comparison of epidemiological and clinical variables in hospitalised patients with bronchiolitis based on length of stay using the chi square test.

| Total % (n=950) | LOS ≤5 days % (n=561) | LOS >5 days % (n=386) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | <0.001 | |||

| <1 | 21.1 | 15.5 | 28.2 | |

| 1–3 | 50.6 | 51.6 | 49.8 | |

| >3 | 28.3 | 32.9 | 22.5 | |

| Sex | 0.889 | |||

| Male | 53.3 | 53.5 | 53.0 | |

| Female | 46.7 | 46.5 | 57.0 | |

| Birth weight (g) | <0.001 | |||

| <2300 | 12.2 | 8.9 | 16.4 | |

| 2300–3100 | 36.7 | 35.3 | 38.4 | |

| >3100 | 51.1 | 55.8 | 45.3 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥37 | 81.5 | 86.8 | 74.8 | |

| 32–36 | 15.6 | 10.5 | 22.0 | |

| <32 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 7.6 | 5.2 | 10.8 | 0.001 |

| C-section | 30.8 | 29.8 | 32.2 | 0.423 |

| Maternal age (years) | 0.303 | |||

| <25 | 26.2 | 27.1 | 25.0 | |

| 25–30 | 28.5 | 28.2 | 28.8 | |

| 30–34 | 25.2 | 26.7 | 23.3 | |

| >34 | 20.2 | 18.0 | 23.0 | |

| Breastfeeding | 40.0 | 38.9 | 41.3 | 0.450 |

| Prenatal tobacco exposure | 17.6 | 17.8 | 17.3 | 0.843 |

| Exposure to smoke | 38.6 | 39.4 | 37.6 | 0.577 |

| Atopy in family | 22.6 | 23.8 | 20.9 | 0.280 |

| Siblings <6 years | 63.4 | 60.5 | 66.8 | 0.054 |

| Siblings 6–14 years | 24.2 | 25.8 | 22.4 | 0.273 |

| Days from onset | 0.032 | |||

| 1 day | 54.0 | 49.8 | 59.3 | |

| 2 days | 22.0 | 24.2 | 19.3 | |

| 3 days | 12.3 | 13.7 | 10.6 | |

| >3 days | 11.7 | 12.4 | 10.8 | |

| Fever >38°C | 37.3 | 36.7 | 39.6 | 0.208 |

| SpO2<92% | 28.8 | 25.4 | 37.2 | 0.001 |

| Oral intake <50% | 31.1 | 28.5 | 34.3 | 0.102 |

| Weight percentile <3rd percentile | 8.0 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 0.002 |

| ABSS | 0.028 | |||

| Mild | 33.0 | 35.7 | 26.4 | |

| Moderate | 62.6 | 59.9 | 66.1 | |

| Severe | 5.4 | 4.4 | 7.5 | |

| Apnoea prior to admission | 10.8 | 6.1 | 16.9 | <0.001 |

| Apnoea during stay | 4.9 | 0.5 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Nasogastric tube feeding | 13.9 | 2.7 | 27.7 | <0.001 |

| PICU admission | 8.5 | 0.5 | 18.4 | <0.001 |

| Severe bacterial infection | 15.5 | 4.2 | 29.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 84.5 | 95.8 | 70.7 | |

| UTI | 3.0 | 1.1 | 5.2 | |

| Respiratory infection | 10.9 | 2.8 | 20.9 | |

| Sepsis | 1.6 | 0.4 | 3.2 | |

| Readmission | 2.1 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 0.009 |

| RSV+ | 77.9 | 75.8 | 80.7 | 0.096 |

ABSS, acute bronchiolitis severity scale; LOS, length of stay; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SpO2, oxygen saturation; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Significant p-values presented in boldface.

Results of the logistic regression analysis of variables associated with increased length of stay in patients hospitalised for bronchiolitis, with the corresponding odds ratios and confidence intervals.

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Birth weight | ||

| <2300g | 2.75 | 1.32–5.70 |

| 2300–3100g | 1.72 | 1.08–2.75 |

| >3100g | 1 (reference) | |

| Age | ||

| <1 month | 4.02 | 1.96–8.26 |

| 1–3 months | 2.95 | 1.60–5.43 |

| >3 months | 1 (reference) | |

| Intake | ||

| <50% | 2.01 | 1.16–3.47 |

| 50–75% | 1.19 | 0.69–2.05 |

| >75% | 1 (reference) | |

| History of apnoea | 2.52 | 1.10–5.74 |

| SBI | 11.95 | 5.09–28.02 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SBI, severe bacterial infection.

Following the introduction of the CPG in 2010, the period comprehending 5 outbreaks should provide a broad enough perspective to assess its impact. Given the southern location of this hospital, October would be generally considered the onset month for AB epidemics, although we found variability within a 4-week range, as has been described previously.2 In other locations in Europe, such as Greece, the season starts in December and peaks in February.15 Approaches that involve vaccination in pregnant women, as is currently done with pertussis, should take these factors into account for the development of preventive strategies.12

Although 24 months was classically considered the age limit for the diagnosis of AB, an increasing number of authors have been focusing their research on the first 12 months of life as a more appropriate age range for the definition of this disease.14,26 The actual pathophysiology of AB in infants aged less than 6 months differs significantly from that of older children, both due to the level of immunologic and functional development as well as the size of the of the respiratory tract. In our series, 93% of the admitted patients were aged less than 6 months, and only 0.5% of admissions due to AB were in patients aged more than 1 year, with a mean age of 2.46 months. Studies published in Spain report that approximately 2.7% of hospital admissions due to AB are in children aged more than 1 year.2

There is great variability in the mean age of the children that are hospitalised, as described in an extensive review of the epidemiological evidence,27 a factor that must certainly influence other variables such as admission to the PICU and mean length of stay. The mean length of stay, both in the ward and in the PICU, must necessarily correlate to the mean age at admission and the proportion of preterm children in the series. If these variables are not standardised, it is not possible to compare the results of different studies. Time-trend studies have found evidence of a decrease in the age at admission in recent years.5,24 Overall, in both the reviewed literature and our own study, the age at admission seems significantly lower compared to the age reported in Spanish studies conducted before the implementation of the CPG, with mean ages of 3.4,28 3.95 and 5.5 months.29

Of the total susceptible population in our catchment area for each year, 15.21% sought care for bronchiolitis at the emergency department and 2.36% required hospitalisation. In previous studies, the reported incidence of hospitalisation has varied, with figures of 2.1%,2 2.3%24 or 4.5%,26 as have its trends over time, including stable,24 decreasing4 and increasing trends.26

All published case series have shown predominance of male patients2,3,7,14 that is more marked among those with non-RSV bronchiolitis (p<0.05). Lower birth weight and lower gestational age are associated with non-RSV bronchiolitis, which is very likely related to the use of palivizumab in Spain (Table 3).

The protective effect of breastfeeding seemed to be stronger in cases of AB caused by viruses other than RSV, as previously described.25 Since RSV is a seasonal virus that does not confer persistent immunity (it produces a modest and short-lived response30,31), breast milk probably does not contain levels of secretory IgA comparable to those achieved against viruses other than RSV, for which immunity is more stable throughout subsequent outbreaks. This could also be the reason why the incidence of hospitalisation due to RSV bronchiolitis in our series remained stable independent of maternal age, contrary to non-RSV cases of AB, in which the incidence decreased with maternal age, a significant result with a p-value of 0.01 (Table 3). The distribution of cases of non-RSV bronchiolitis showed a less explosive and more uniform pattern than the distribution of RSV cases, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Prenatal and environmental exposure to tobacco, traditionally considered a risk factor for admission, clearly continues to be a relevant factor.26,32 In our series, its impact was greater on non-RSV cases (p<0.01; Table 3), although it was not associated with a longer length of stay (Table 4). We also found no association of fever with length of stay, and fever was present at the onset of AB in 37.3% of the cases and more prevalent in patients with RSV involvement (p<0.01; Table 3).

Apnoea prior to admission as a reason for seeking care associated with AB exhibited a different pattern and was more frequent in cases of non-RSV bronchiolitis. The 5% incidence of apnoea during hospitalisation was consistent with previous studies.33 Apnoea associated with AB can be obstructive, central or mixed. It is likely that apnoeic episodes prior to admission are predominantly obstructive and that episodes are less frequent during hospitalisation due to the respiratory support received at hospital. When it came to this variable, there seemed to be differences between RSV versus non-RSV cases (Table 3). The presence of apnoea prior to admission reported by caregivers was a risk factor for increased length of stay (Tables 4 and 5).

When it came to the need for special care, nasogastric tube feeding was more frequent in RSV cases, probably due to the greater severity of the bronchiolitis, but we found no difference in the incidence of PICU admission, which in our study amounted to 8.5% of patients admitted to the ward. In our hospital, we do not use high-flow nasal cannula therapy in the paediatric ward due to its cost and the lack of evidence on its efficacy and safety. Patients that required high-flow therapy were admitted to the PICU, which did not result in a larger proportion of PICU admissions relative to previous studies, in which it ranges between 6% and 13%.5,14,15,25 Although it is used widely and has shown promising results, it has not yet been recommended for use at the ward level in a recent review.34

Our findings relating to heart disease, neurologic disease and bronchopulmonary dysplasia were similar to those of other studies.24,27 Their presence was an independent risk factor for admission to the PICU and prolonged length of stay. For that reason, we excluded these cases from our analysis of length of stay.

The presence of siblings in the household, a family history of atopy and the time elapsed since the onset of disease were not associated with the aetiology of AB or length of stay. Out of the remaining variables summarised in Table 4, multivariate logistic regression analysis identified the following as risk factors for increased length of stay: low birth weight, age, history of apnoea prior to admission and reduction in oral intake by more than 50% (Table 5). This was highly consistent with the previous literature.7

Bacterial co-infection of the lower respiratory tract, in an epithelium destroyed by a virus like RSV, in patients too young for vaccination against pneumoccocus or with incomplete vaccination is not given the importance it deserves in the various studies published to date, although the current evidence suffices to assert that it is frequently involved in cases that require admission to the PICU.21,25 Co-infection is a clear risk factor for increased length of stay. Recent studies have found a prevalence of co-infection of up to 29% in children with viral illness.22 In our series, the clinical diagnosis of respiratory bacterial co-infection, whether confirmed or suspected, was substantially more frequent than the diagnosis of severe UTI.

Our study has the limitations inherent in all retrospective studies, including the challenges posed by data collection and missing data. We must also add the fact that the study was restricted to hospitalised patients and to a single centre. We did not collect information on potential visits to primary care facilities prior to admission, which amount to 21% of patients per year in other case series.2 We also did not take into account the effects of viral co-infection, which is estimated to occur in 30% of cases,7 although their presence, as we already noted, is not required for diagnosis. Lastly, bacterial co-infections are particularly difficult to discern in respiratory illness, as acute phase reactants may be elevated in some viral infections.

ConclusionsWe found that in our region the timing of outbreak onset varied within a range of four weeks. Five years from the implantation of the CPG,11 the incidence of hospitalisation is of around 2.3% and seems stable in relation to previous studies. The mean age of patients has decreased to 2.4 months, although the proportion of patients admitted to the PICU remains similar, at 8.5%.

The independent risk factors for an increased length of stay found in our study were low birth weight, age less than 1 month, history of apnoea prior to admission, reduction in oral intake of more than 50% and severe bacterial co-infection, in which the prevalence of respiratory infection was greater than that of severe UTI.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos-Fernández JM, Pedrero-Segura E, Gutiérrez-Bedmar M, Delgado-Martín B, Cordón-Martínez AM, Moreno-Pérez D, et al. Epidemiología de los ingresos por bronquiolitis en el sur de Europa: análisis de las epidemias 2010-2015. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:260–268.