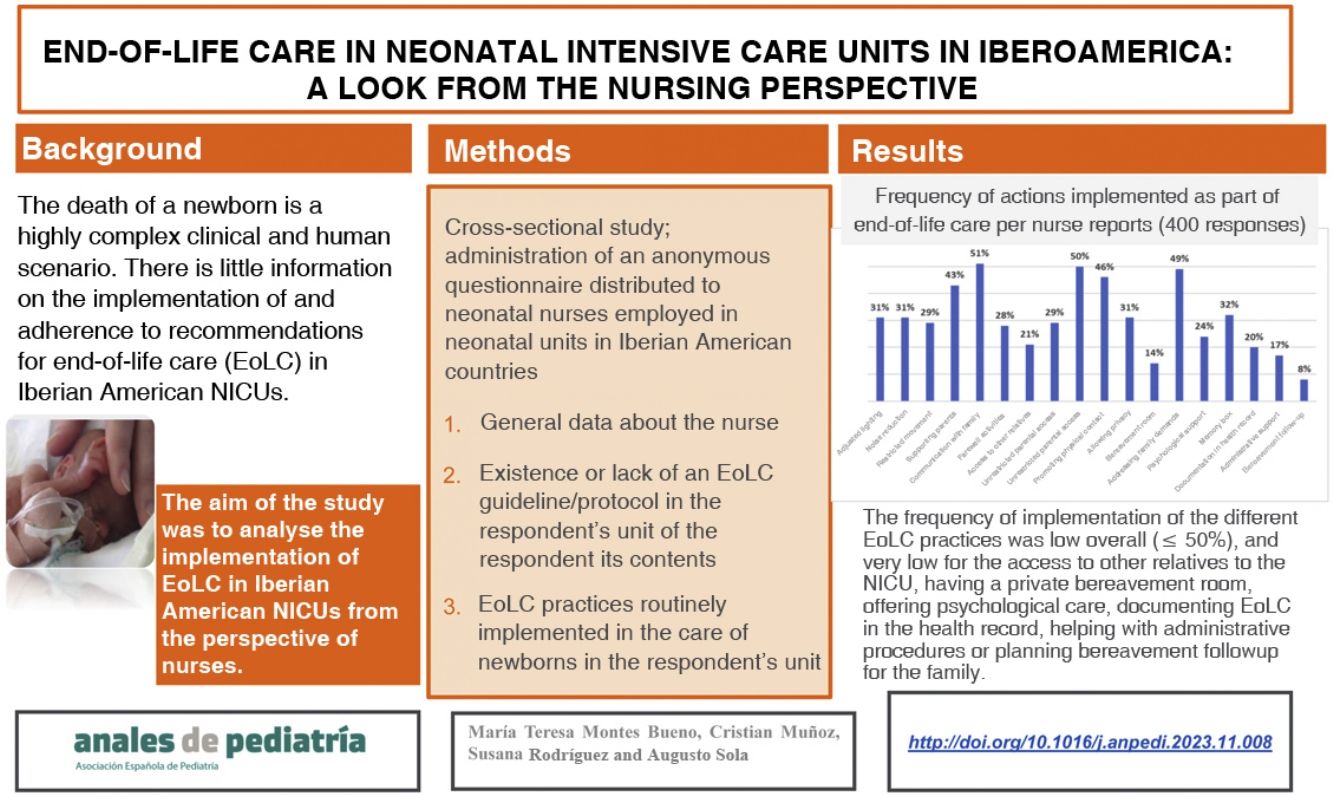

End-of-life care (ELC) represents a quality milestone in neonatal intensive care units (NICU). The objective of this study was to explore how ELC are carried out in NICUs in Iberoamerica.

MethodsCross-sectional study, through the administration of an anonymous survey sent to neonatal nursing professionals. The survey included general data and work activity data; existence and contents of ELC protocols in the NICU and training received. The survey was distributed by email and published on official SIBEN social networks. REDCap and STATA 14.0 software were used for data collection and analysis.

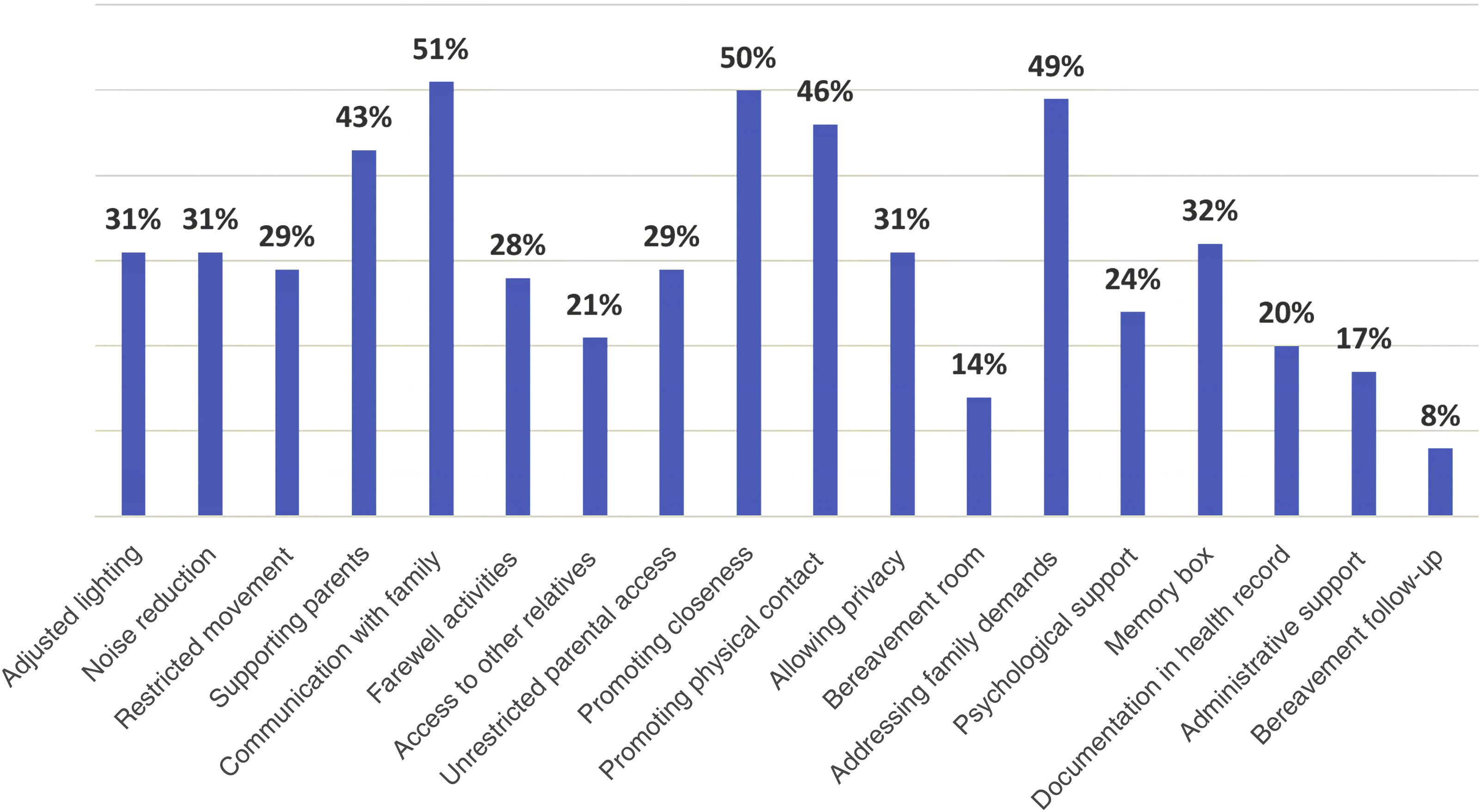

ResultsWe obtained 400 responses from nurses from 11 countries in the Ibero-American region. 86% of the respondents are directly responsible for providing ELC, although 48% of them said they had not received training on this subject. Only 67 (17%) state that the NICU in which they work has a protocol that establishes a strategy for performing the ELC. Finally, the actions that are implemented during the ELC are globally infrequent (≤50%) in all the items explored and very infrequent (<20%) in relation to allowing free access to family members, having privacy, providing psychological assistance, register the process in the medical record, assist with bureaucratic processes or grant a follow-up plan for grief.

ConclusionMost of the nursing professionals surveyed are directly responsible for this care, do not have protocols, have not received training, and consider that the ELC could be significantly improved. Strategies for ELCs in the Ibero-American region need to be optimized.

Los cuidados al final de la vida (CFV) son una parte fundamental de la asistencia al recién nacido ingresado en una unidad de cuidados intensivos neonatal (UCIN). El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar cómo se implementan los CFV en UCIN de Iberoamérica.

MétodosEstudio trasversal realizado en 2022 mediante encuesta vía email y redes oficiales de SIBEN a profesionales de enfermería de UCIN de países de Iberoamérica, sobre aspectos relacionados con los CFV. Recolección y análisis de datos con REDCap y STATA 14.0.

ResultadosObtuvimos 400 respuestas de enfermeros/as de 11 países, el 73% procedentes de hospitales terciarios. El 86% de los respondedores eran responsables directos de brindar CFV, si bien 48% dijeron no haber recibido formación. Solo 67 (17%) afirmaron que la UCIN en la que trabajan cuenta con un protocolo. Las acciones que se implementan durante los CFV fueron infrecuentes (≤ 50%) en todos los ítems explorados y muy poco frecuentes (<20%) en permitir el acceso libre de familiares, contar con privacidad, brindar asistencia psicológica, registrar el proceso en la historia clínica, asistir con los procesos burocráticos u otorgar un plan de seguimiento para el duelo.

ConclusiónLa mayoría de los profesionales de enfermería encuestados eran responsables directos de proveer CFV, pero no contaban con protocolos, no habían recibido capacitación y consideraron que los CFV podrían mejorarse significativamente. Las estrategias para los CFV en la región Iberoamericana requieren ser optimizadas.

Scientific and technological advances made in the past few decades have had a direct impact on the evolution of neonatal care, allowing the survival of severely ill or very premature newborn infants. Sadly, neonatal death is a frequent event in neonatal care units and it is a very complex clinical and human scenario, and neonatal care teams that support affected families need not only be committed, but also skilled to manage it appropriately. In recent decades, the principles of end-of-life care (EoLC) have been progressively integrated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) setting to improve the quality of care.1

There is evidence that EoLC constitutes a key and necessary quality milestone in the NICU, and that the role of the nurse in its delivery is essential and requires continuous training.2,3

Nurses are key agents in this challenging situation, as they are continuously present during this stage and facilitate communication between the care team and the family.4 Some neonatal deaths follow the decision to withdraw or withhold life-prolonging treatment, although this varies between cultures and countries. In NICUs in Europe and the United States, these decisions are frequent and chiefly based on a poor prognosis in terms of survival and present and future quality of life.5–7

There are fewer data for neonatal units in the Latin American region, where most neonatal deaths could be prevented with quality perinatal care. The Sociedad Iberoamericana de Neonatología (SIBEN, Ibero-American Society of Neonatology)8 has been working on the training of neonatal care teams for more than 20 years with the aim of improving outcomes in the region. According to data collected by the SIBEN network9 corresponding to 24 NICUs in 10 Iberian American countries, the overall mortality in the region is high and varies widely between units; in 2022, the mortality was 25% for neonates with birth weights less than 1500 g and 8% for those with greater birth weights. That means that on that year, many neonates died in NICUs and their families had to go through this harrowing experience. Health care staff, and specifically nursing staff, supported families to a varying extent and provided care through the neonatal death process.

To guide the coordination of EoLC delivery by neonatal care teams, different institutions and societies, including the SIBEN,3 have developed recommendations for the management of these complex scenarios from a scientific, ethical and human perspective.10–12

At present, there is little evidence on whether these recommendations are being applied and how EoLC is implemented in NICUs in Iberian America. This information could be useful to assess and identify barriers as well as opportunities for improvement in this neonatal care field.

The aim of the study was to analyse whether and how EoLC services are implemented in Iberian American NICUs from the perspective of the nursing staff.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study between March and June 2022, through an anonymous questionnaire distributed to neonatal nurses working in neonatal care units in Iberian America. The questionnaire was initially distributed by mass mailing to nurses affiliated to the SIBEN and then by the publication of a link to the online questionnaire in the official social media accounts of the SIBEN (Instagram and Facebook). The SIBEN has members in 20 countries, although the representation is uneven, with the largest memberships corresponding to Argentina, Peru and Mexico. In addition, access to the SIBEN social media accounts is also heterogeneous, with visits made most frequently from Argentina and Peru.

We designed an ad hoc questionnaire with the REDCap software, developed by Vanderbilt University for research data collection. After developing the items and entering them into an online form, we proceeded to assess its comprehension and relevance through a pilot survey of nurses in different countries.

The questionnaire was structured into 3 sections: (1) general characteristics of the nurse/respondent (age, sex, country) and their professional activity: years of experience, characteristics of the NICU, role in the unit, categorised as clinical, administrative or both, experience in communicating with and/or supporting families of deceased newborns and training received on the subject; (2) whether or not there was an EoLC guideline or protocol in the unit where they worked and the aspects it included and (3) practices usually implemented in the delivery of neonatal EoLC in the unit where they worked.

To standardise important aspects of EoLC, the questionnaire included 18 items used to assess care practices in regard to (a) environmental measures (adjust ambient lighting, reduce ambient noise, limit movement), and (b) family support:

- •

Supporting parents.

- •

Maintaining communication with the family.

- •

Promoting farewell activities (photos, bathing, clothing, etc.).

- •

Allowing access to other relatives as desired by the parents.

- •

Allowing parents to stay with the neonate around the clock.

- •

Encouraging and facilitating closeness and physical contact with the newborn, as well as skin-to-skin contact or holding the newborn.

- •

Giving privacy (arranging a private space within the unit by means of curtains, folding screens, etc) or having a dedicated, private bereavement room.

- •

Listening and responding to family needs (religious, cultural, etc).

- •

Providing specialised psychological care to parents.

- •

Giving parents keepsakes to remember their baby (memory box).

- •

Documenting the delivery of EoLC in the health record.

- •

Help with any necessary paperwork, formalities or arrangements (administrative support).

- •

Establishing a bereavement follow-up plan.

This list was based on the recommendations for EoLC of the SIBEN.3

Lastly, we added an item concerning the perceived changes in EoLC services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data were collected with REDCap and summarised using descriptive statistics with the STATA software, version 14.0. The data were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion and frequency and percentage distributions and compared using the χ2 test.2

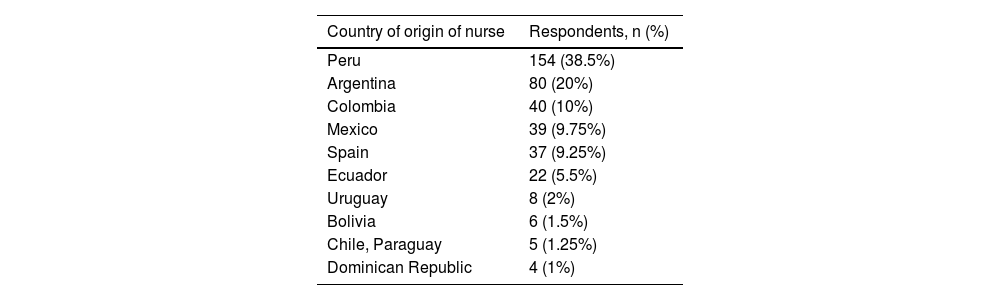

ResultsWe received 400 complete responses from 11 countries. The response rate was 20% for the mass mailing, and the link posted in social media only yielded another 25 responses. Ninety percent of the responses were submitted from Peru, Argentina, Mexico, Spain and Colombia; Table 1 presents the distribution of the nurses that responded by country of residence.

Distribution of responses by country.

| Country of origin of nurse | Respondents, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Peru | 154 (38.5%) |

| Argentina | 80 (20%) |

| Colombia | 40 (10%) |

| Mexico | 39 (9.75%) |

| Spain | 37 (9.25%) |

| Ecuador | 22 (5.5%) |

| Uruguay | 8 (2%) |

| Bolivia | 6 (1.5%) |

| Chile, Paraguay | 5 (1.25%) |

| Dominican Republic | 4 (1%) |

N = 400 nurses; more than 1 nurse may have responded per hospital.

Seventy-three percent of nurses that responded worked in a high-complexity or level III unit, and 77% worked in the public health sector. The mean experience of respondents in neonatal care was 19 years (standard deviation [SD], 7), 95% were female, and the mean age was 44 years (SD, 6).

Sixty-eight percent of the nurses (272) were exclusively dedicated to care delivery, 13% (54) worked in administrative roles and 19% (74) performed both clinical and administrative tasks.

In 344 cases (86%), the nurse that completed the questionnaire reported frequently being responsible for the direct care of the neonate and the family at the time of the death of the child. Nearly half (48%) reported that they had not received any specific training on EoLC, despite recognising its need and importance.

Only 17% (67) of respondents reported that their units had an established protocol or guideline for delivery of EoLC, 250 (62%) reported there was none and 21% that they did not know whether there was one. Among the 67 nurses who worked in units with protocols, only 57 had read them and knew their recommendations.

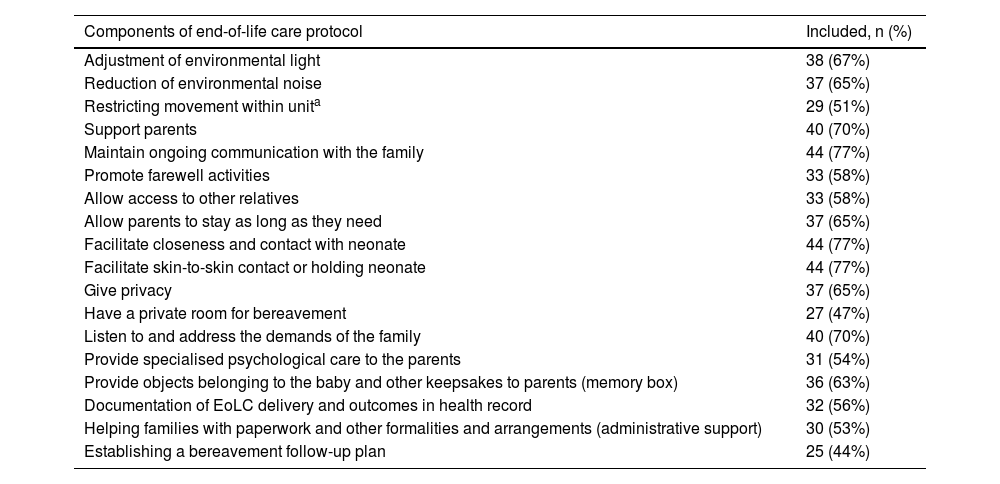

Table 2 describes the frequency of the elements included in EoLC protocols based on the responses of this subset of nurses. Fewer than 50% of protocols considered the need to have a private bereavement room and set up bereavement follow-up plans.

Components of the end-of-life care protocols, as reported by 57 nurses.

| Components of end-of-life care protocol | Included, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Adjustment of environmental light | 38 (67%) |

| Reduction of environmental noise | 37 (65%) |

| Restricting movement within unita | 29 (51%) |

| Support parents | 40 (70%) |

| Maintain ongoing communication with the family | 44 (77%) |

| Promote farewell activities | 33 (58%) |

| Allow access to other relatives | 33 (58%) |

| Allow parents to stay as long as they need | 37 (65%) |

| Facilitate closeness and contact with neonate | 44 (77%) |

| Facilitate skin-to-skin contact or holding neonate | 44 (77%) |

| Give privacy | 37 (65%) |

| Have a private room for bereavement | 27 (47%) |

| Listen to and address the demands of the family | 40 (70%) |

| Provide specialised psychological care to the parents | 31 (54%) |

| Provide objects belonging to the baby and other keepsakes to parents (memory box) | 36 (63%) |

| Documentation of EoLC delivery and outcomes in health record | 32 (56%) |

| Helping families with paperwork and other formalities and arrangements (administrative support) | 30 (53%) |

| Establishing a bereavement follow-up plan | 25 (44%) |

EoLC, end-of-life care.

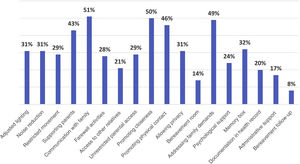

Fig. 1 shows the percentage of adherence with different aspects of EoLC in the NICUs as reported by the 400 nurses. Overall, the frequency of implementation of the different EoLC practices was low (≤50%), with a particularly low frequency of allowing access to other relatives, having a private bereavement room, offering psychological care, documenting EoLC in the health record, helping with administrative procedures or planning bereavement follow-up for the family.

When we compared the frequency of implementation of EoLC practices based on whether or not there was an established protocol, we did not find any significant differences.

In addition, considering that units in Spain could have rates of treatment withdrawal or withholding and care protocols similar to other countries in the European region, we decided to make a separate analysis of this subgroup to determine if there were differences, and found that, compared to the NICUs in Latin America, a higher proportion of nurses in Spain reported having received training (65%) and knew the protocol of the unit (51%), and the frequency of implementation of EoLC practices was greater overall (49%–54%), except for the documentation of EoLC in the health record (35%), assistance with administrative procedures (32%) and bereavement follow-up (24%).

Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, 48% of nurses reported that there was a negative impact on EoLC, and 69% that parental access to the NICU was totally or partially restricted, and that EoLC practices had yet to be fully restored after the pandemic.

DiscussionOur findings show that, from the nurses’ perspective, the approach to EoLC in Iberian America needs to be improved. Protocols are infrequent in NICUs, as are training opportunities for the care team. Most nurses stated that they engaged in EoLC in their clinical practice, despite reporting barriers to its delivery.

A high percentage of respondents stated that their units did not have EoLC guidelines, that they did not know whether such guidelines existed or that there were guidelines but they had not read them. This highlights the urgent need not only to establish a protocol in each unit, but to also to ensure its dissemination among the entire care team and the development of multidisciplinary strategies for their implementation. Despite the importance attributed to clinical guidelines and protocols, the effective application of their contents to clinical practice has yet to be achieved, as there are various barriers that hinder it.13

End-of-life care practices related to adjusting the NICU environment, allowing privacy, recording care measures in the health record or bereavement follow-up are not implemented in more than half of the units, based on the reports of nurses working in the region. Most of these practices do not require financial investment or technological resources, and just entail a shift in the care model and a belief in their importance for patient care.14 Their implementation entails agreements between care team members and organizational changes within each unit. There are publications detailing the recommended structures and processes to inform EoLC programme development.15 Making memory boxes available, for instance, requires appointing a staff member in each unit to handle the task, establishing the possible contents of the box and identifying an appropriate time for their delivery.16 A bereavement follow-up plan can include sending letters to the relatives of the deceased child on specific dates, meetings with the parents and giving families access to a counselling team to address arising questions or needs.17 Each of these practices requires leadership, organization, training and implementation.

There are limitations to our study. The response rate was low, even though participation was anonymous and the questionnaire was simple and could be completed quickly. We attempted to increase the response rate by setting up 2 scheduled repeat mass mailings including the addresses from which a response had not been obtained. It is possible that the low response rate reflects, to a certain extent, the problems currently affecting the delivery of EoLC. Last of all, we posted the objectives of the survey in the social media accounts of the SIBEN and requested completion of the questionnaire through the mobile phone. However, the response rate was still lower than expected, which may be indicative of a lack of interest on the subject, deficient training, difficulty managing end-of-life situations, dissatisfaction with this type of studies, which require devoting time to responding, short as it may be, and other factors that were beyond our control.

The low response rate was not consistent with similar studies carried out in Europe.18 However, there are also previous publications reporting low participation in studies involving these subjects.19

Furthermore, the responses reflect the experiences and opinions of individual nurses, and not the institutional stance of each unit, nor the actual delivery of EoLC to neonates. The system used for distributing the questionnaire and receiving responses did not allow for a single individual to submit more than one response, but could not determine whether more than one respondent worked in the same facility, which means that some units may have been overrepresented.

Although our study was not designed to compare the perspective of EoLC nurses in different countries, we found that the results were more favourable in Spanish units, which could have affected the overall results.

There were also some aspects that were not addressed in the survey, such as lactation/breastfeeding practices,20 pain management,21 bereavement photography22 or transcultural factors21 that are also important in EoLC, whose exploration we deferred to future studies to avoid increasing the length and complexity of the questionnaire.

Lastly, analysing the involvement in EoLC of the nurses in charge of these patients and their families, which can cause significant emotional stress, was not among our objectives. Failure to detect or adequately manage emotional stress can have a deleterious impact on performance, reducing motivation or creating bias in decision-making.23,24

In this context, the development of specific emotional skills is essential in the NICU setting, where, unfortunately, the death of a newborn is not an exceptional event. Specific interventions, such as the introduction of self-care measures, gathering the entire care team to reflect on the cases of deceased infants and improving training on communication skills contribute to improving the quality of EoLC and is also a form of care for the care team itself.1,25–27

ConclusionThere is an urgent need to change the implementation of EoLC in the Iberian American region. Most of the nursing professionals that responded to the survey were directly responsible for implementing these services, had not received training on the subject and believed that EoLC could improve substantially.

The development of EoLC protocols with a multidisciplinary approach and structure and of a comprehensive scope, including strategies for the dissemination and implementation of EoLC, could help optimise quality of care for families that become very vulnerable as they go through the devastating experience of losing a newborn infant.

The constant training, commitment and involvement of the nursing team are key for the successful implementation and monitoring of these changes.

FundingSociedad Iberoamericana de Neonatología (SIBEN).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank graduate Virginia Kulik, of the SIBEN, for her valuable collaboration in data handling, and the nurses members of the nursing chapter of the SIBEN for their help in validating the questionnaire.

Our thanks, too, to all the colleagues in the Latin American region that responded to the survey.

We would also like to acknowledge Cicely Saunders, a British nurse, social worker, physician and writer (1918–2005), who founded the first modern hospice and defined and pioneered the field and culture of palliative care. She stated: “You matter because you are you. You matter to the last moment of your life, and we will do all we can, not only to help you die peacefully, but also to live until you die.” (Cicely Saunders).