The emotional impact on parents of the diagnosis of an anomaly in the foetus during pregnancy merits reflection. During this stage, neonatologists have the opportunity to carry out a prenatal intervention by conducting an interview with the family to answer any questions and start the shared decision-making process. This prenatal consultation has potential benefits and is also a challenge for clinicians,1 who must have the necessary communication skills to adapt the conversation to fit the needs of the parents, empower them in decision-making and provide emotional support.2 However, at present there is little evidence to guide prenatal counselling when disease is diagnosed in the foetus, although there are some published works devoted to it in the context of prematurity.1,3–5

With the primary objective of determining whether neonatologists in Spain offer families an interview during the pregnancy if foetal disease is detected, we carried out a nationwide survey. As secondary objectives, we assessed whether the care level of the unit was associated with the probability of offering a prenatal interview and whether residents in paediatrics received specific training on this subject.

We developed an ad hoc questionnaire, as we did not find any validated instruments that fit the area of interest of the study. We distributed the questionnaire in 2019 through Google® Forms to 167 hospitals with neonatal units throughout Spain.

Sixty-six percent of surveyed facilities participated in the study (N = 110). Of this total, 83% were public hospitals, and the rest were private or state-contracted private hospitals. When it came to the care level of the neonatal unit,6 57% of hospitals that participated in the survey had high-complexity units (level III), 35% level II units and 8% level I units.

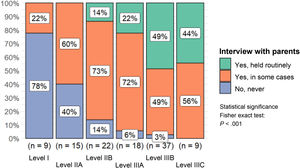

When it came to the practice of conducting interviews with parents during the pregnancy following the detection of foetal disease, 57% of hospitals reported that these interviews were only conducted “in select cases”, 27% that they were conducted “routinely” and 16% “never” conducted. The analysis of the data evinced the association between the care level of the neonatal unit and the answer to this question (Fig. 1). Most of the hospitals that had a neonatal intensive care unit offered a prenatal interview at least in “selected cases” or “routinely”. However, up to 77% of hospitals that had lower-level units reported not offering any information prenatally in any case. Thus, we found that prenatal paediatric intervention is less likely the lower the level of care of the neonatal unit (Fisher exact test, P < .001). We did not find statistically significant differences (P < .05) in the answers to this item based on the ownership of the hospital (public, contracted or private).

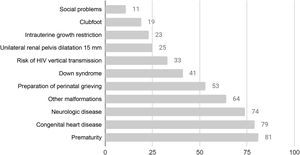

In the separate analysis of the data on the hospitals that reported offering prenatal counselling (Fig. 2), 97% stated it was only offered in the case of disease of a certain complexity. A more detailed analysis revealed that the condition most frequently involved is prematurity (81%), followed by congenital heart diseases (79%) and neurologic diseases (74%). A prenatal interview was less likely in the case of other diagnoses such as Down syndrome, intrauterine growth restriction or renal or infectious disease. On the other hand, only 53% of these hospitals had an active approach during pregnancy to prepare for the future grieving process in the case of poor life expectancy.

Lastly, 91% of respondents reported not having received training on how to carry out this type of interview during the paediatrics residency.

Our results show that prenatal paediatric intervention is infrequent in Spain and is offered mainly in higher-level hospitals and in specific situations. Thus, this is an area for improvement in Spain in neonatal care and in the training of medical residents in this speciality. It would be interesting to carry out studies to explore the expectations of families as regards prenatal counselling to better adapt the interview to their needs and identify the diseases for which this intervention provides benefits to the families or an excess of information can be an additional source of stress.

The high response rate makes this initial approximation to the subject robust, although we were unable to compare our findings with those of other authors, as we did not find any similar studies in the reviewed literature.

Please cite this article as: López González MF, Vela Enríquez F, García Martín R, Vargas Pérez M. ¿Asesoramos los neonatólogos en España a los padres durante el embarazo? Encuesta nacional. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:367–369.

Previous presentation: this study was presented at the XXVII Congress of Neonatology and Perinatal Medicine, October 3–4, 2019, Madrid, Spain. Session of oral communications of research projects to apply for full membership in the Sociedad Española de Neonatología.