Although thyroid cancer is the most frequent malignancy of the endocrine system, it is very rare in children. Ninety percent of paediatric cases correspond to differentiated thyroid cancers (DTCs). Secondary thyroid cancer is the most frequent type in children previously treated with head and neck irradiation. The Spanish Registry of Child Tumours (Registro Español de Tumores Infantiles, RETI-SEHOP) reported an incidence of 3–4 cases per 106 children in the 1980–2013 period, similar to the incidence reported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (ACCIS) in Europe. The Registry also described an increase in the annual incidence that has also been observed in the United States.1 Thyroid cancer in children usually presents as a nodule in the thyroid or regional lymphadenopathy. Compared to adults, the diseases tends to be more advanced at the time of diagnosis, with metastases in regional cervical lymph nodes and distant metastatic disease (lungs), and a greater rate of recurrence.2 Traditionally, treatment has consisted of total thyroidectomy, excision of local and regional metastases, administration of radioactive iodine (I131) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression, which achieved high cure rates. However, long-term longitudinal studies have revealed an increased mortality in survivors due to secondary cancers in patients that received radiation therapy.3 Due to the low incidence of this cancer, trials have not been conducted to optimise treatment, which is based on data from retrospective studies and, more recently, in the 2015 guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (ATA).4

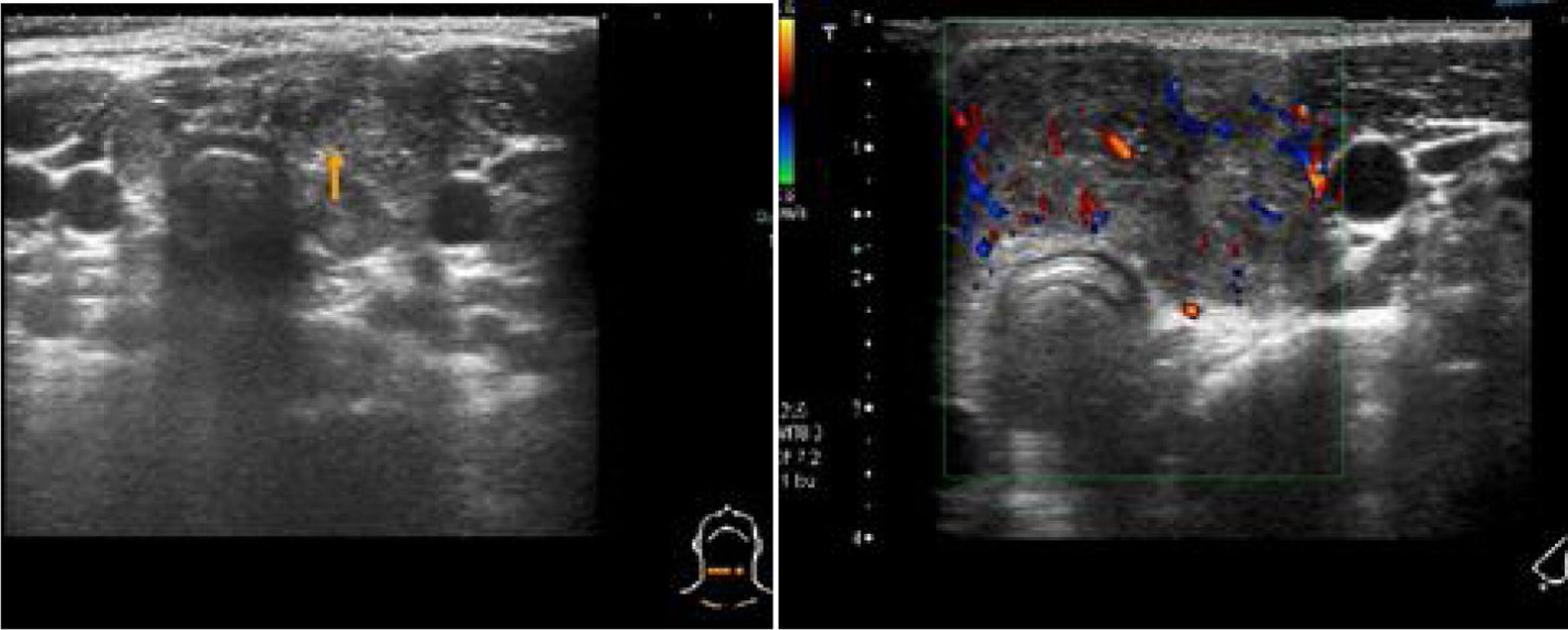

We present the cases of 3 patients with a diagnosis of differentiated papillary thyroid cancer in 2011. The patients presented with a thyroid nodule or cervical lymphadenopathy. None had relevant risk factors or a family history of DTC. The assessment included a cervical ultrasound examination that found signs of malignancy (Fig. 1). The findings of fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the lesions was compatible with papillary thyroid cancer with lymph node involvement in all 3 cases. The results of blood tests were normal. The patients underwent a total thyroidectomy with lymph node dissection (central and lateral). This was followed by initiation of TSH suppression with levothyroxine. All patients experienced hypoparathyroidism as an immediate complication of surgery. Later on, having suspended treatment with levothyroxine, they underwent ablation of the thyroid remnant with I131, with the dose calculated based on body weight (50–120mCi). The first whole-body scan revealed metastases in the lung and extensive lymph node involvement (AJCC/UICC 2 T3-4a N1b M1, ATA Pediatrics High Risk), and the patients required between 3 and 6 doses. One patient had a recurrence in the form of a malignant contralateral lymph node, which was removed after diagnosis by means of ultrasound and measurement of thyroglobulin in a FNAB specimen. The follow-up included stimulated thyroglobulin testing, measurement of antithyroglobulin antibodies, scintigraphy, positron-emission tomography or computed tomography scans and cervical ultrasound examinations. Two patients continue to have residual disease in the lungs (Table 1).

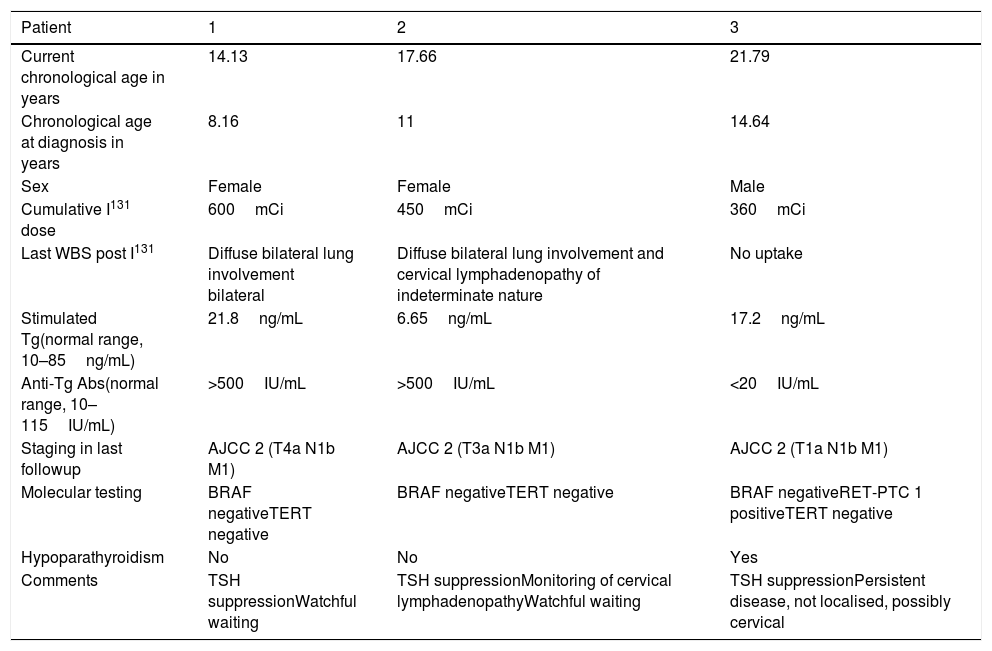

Current outcomes in patients, 6 years after diagnosis.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current chronological age in years | 14.13 | 17.66 | 21.79 |

| Chronological age at diagnosis in years | 8.16 | 11 | 14.64 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male |

| Cumulative I131 dose | 600mCi | 450mCi | 360mCi |

| Last WBS post I131 | Diffuse bilateral lung involvement bilateral | Diffuse bilateral lung involvement and cervical lymphadenopathy of indeterminate nature | No uptake |

| Stimulated Tg(normal range, 10–85ng/mL) | 21.8ng/mL | 6.65ng/mL | 17.2ng/mL |

| Anti-Tg Abs(normal range, 10–115IU/mL) | >500IU/mL | >500IU/mL | <20IU/mL |

| Staging in last followup | AJCC 2 (T4a N1b M1) | AJCC 2 (T3a N1b M1) | AJCC 2 (T1a N1b M1) |

| Molecular testing | BRAF negativeTERT negative | BRAF negativeTERT negative | BRAF negativeRET-PTC 1 positiveTERT negative |

| Hypoparathyroidism | No | No | Yes |

| Comments | TSH suppressionWatchful waiting | TSH suppressionMonitoring of cervical lymphadenopathyWatchful waiting | TSH suppressionPersistent disease, not localised, possibly cervical |

Staging: AJCC/UICC II.

Anti-Tg Abs, antithyroglobulin antibodies; Tg, thyroglobulin (tested after suspending levothyroxine); WBS, whole body scan after treatment with radioactive iodine.

The diagnosis of 3 cases of DTC in one year is unusual in our region (population aged 0–14 years in Castilla-La Mancha in 2010–2013 period, 326958). This could be related to the increased incidence described worldwide, which does not seem to be attributable solely to advances in diagnostic techniques. In our hospital, there have been no new cases since, so it is possible that this cluster was the product of chance. The increased predisposition to thyroid carcinogenesis in childhood and adolescence suggests a possible link to exposure to ionising radiation or chemicals early in life.1 We did not identify any risk factors in our patients. As described in the literature, the combination of ultrasound examination and FNAB offered a high diagnostic yield. The histological examination of thyroid tissue obtained by means of FNAB is a well-established method for diagnosis of thyroid nodules in adults due to its high accuracy, but this approach is not widely accepted in the paediatrics field, where surgery is in some cases the initial intervention.2 The new guidelines of the ATA recommend this approach, basing the management on the clinical presentation and ultrasound findings rather than the size of the nodule, and reserving surgery as first-line treatment for hyperfunctioning nodules or nodules with indeterminate histological findings.4 The recommended surgical approach, which was applied in our patients, is total or partial thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection and selective dissection of lateral lymph nodes. This aggressive approach is associated with a higher incidence of complications and should be performed in specialised facilities. In the cases presented here, the patients developed hypoparathyroidism after surgery, and one had Horner syndrome after surgical resection of a recurrence in the lymph nodes. The high incidence of complications could have been due to the extension of the surgery and the younger age of the patients. Our patients received different doses of I131 based on disease extension. There is no consensus on the use of radiotherapy in children, and at present it is recommended in cases with local, regional or distant residual disease or involving iodine-avid tissues, planning the treatment on a case-to-case bases if more than 1 dose is needed due to the risk of long-term complications.5 Despite the updated guidelines for management published by the ATA, further research is necessary to optimise treatment.

Please cite this article as: Villalba Castaño C, Carcavilla Urquí A, Aragonés Gallego Á, Sastre Marcos J, Morlan López MÁ. Diagnóstico de 3 casos de cáncer de tiroides en un año. An Pediatr (Barc). 2019;90:397–399.