Data surrounding palliative sedation in pediatric patients is scarce. Our objective is to assess the utility of creating a quality standard for pediatric palliative sedation.

Material and methodsA non-systematic review of the literature was used to find recommendations for pediatric palliative sedation, after which a definition was established based on three items: (1) indication, (2) consent, and (3) application. Afterwards, a retrospective analysis of palliative sedations applied by our unit over 5 years was performed.

ResultsOut of 163 patients, palliative sedation was applied in 20, in 17 of them by our unit (14/20 males; median: 11.9 years). Twelve patients had oncological diseases, seven had neurological conditions, and one had a polymalformative syndrome. Nine patients had more than one symptom at the time of PS initiation with pain (11/17) and dyspnoea (10/17) being the most frequent. As for the definition, only three patients achieved a global completion, with the registration of the consent, specification of refractoriness and the establishment of an adequate initial sedative dose being the areas with more possible improvement.

ConclusionsThe application of the definition allowed us to analyze and find areas of improvement for our clinical practice of palliative sedation in pediatric patients.

Existen pocos datos referentes a la práctica de sedación paliativa en población pediátrica. El objetivo de este estudio es crear una definición estandarizada de sedación paliativa para población pediátrica y aplicarlo en una Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos.

Material y métodosSe realizó una revisión no sistemática de la literatura en búsqueda de la evidencia y recomendaciones existentes para la práctica de sedación en población pediátrica, tras lo cual se creó una definición de sedación paliativa basada en tres ítems: 1. Indicación 2. Consentimiento y 3. Aplicación. Posteriormente se realizó una revisión retrospectiva de registros clínicos para analizar la práctica de sedación paliativa atendidos por la Unidad de Atención Integral Paliativa Pediátrica de Madrid (UAIPPM) en un periodo de cinco años (enero 2013-diciembre 2017).

ResultadosDe 163 pacientes analizados, la sedación se aplicó en 20, 17 pacientes de la propia Unidad (70% varones; mediana de edad: 11,9 años); 12 pacientes padecían cáncer, siete enfermedades neurológicas y uno un síndrome polimalformativo; 52,9% pacientes sufrían más de un síntoma en el momento de indicar la sedación paliativa, siendo el dolor (64,7%) y la disnea (58,8%) los más frecuentes. En cuanto a la definición, sólo tres pacientes consiguieron una cumplimentación global de la misma, siendo el registro del consentimiento informado el área con mayor potencial de mejora.

ConclusionesLa evaluación basada en una definición estandarizada permitió definir la práctica de sedación paliativa en nuestra Unidad y encontrar áreas potenciales de mejora.

Palliative sedation is defined as the use of one or more drugs to reduce the level of consciousness in a patient in order to alleviate the suffering produced by one or more refractory symptoms.1,2 Although its definition varies,3 most guidelines coincide on certain points. However, the evidence on the subject is scarce, especially in the paediatric population,4–6 for which the literature is limited to a few case series.5,7–10 Despite the fact that the population of paediatric patients with palliative care needs is known to differ from the adult population,11–13 there are no specific guidelines for this age group, which complicates the delivery of palliative sedation for paediatric palliative care teams, as only a few studies have analysed these practices.

In the study presented here, we analysed palliative care practices in the pediatric palliative care unit (PPCU) of the Community of Madrid (CM), Spain, over a period of 5 years through the creation and application of a standardised definition.

Material and methodsThe study was structured in 2 phases:

Phase 1: defining palliative sedationNon-systematic review of the literature on palliative sedation. The aim was to identify commonalities in the current literature that could be turned to items used to evaluate the definition.

Our search yielded a total of 11 national and international guidelines and one chapter in a reference book. Since the paediatric literature on the subject mainly consisted of case series,4,5,7–10,14 and due to the lack of specific guidelines beyond some references to paediatric palliative care,6,15,16 we selected the general guidelines for adult palliative care as the framework for the definition, adapting those aspects affected by the particularities of the paediatric population (drug dosage, informed consent…). Specifically, we used as reference the guidelines of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC)2 and of the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO)1 at the international level and the guidelines of the Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (Spanish Society of Palliative Care, SECPAL) and Council General of Official Boards of Physicians of Spain17 and of the Spanish Ministry of Health18 at the national level.

We identified 5 common points in these documents: 1) Presence of intractable suffering caused by refractory symptoms. 2) Presence of “terminal” illness. 3) Need to have complex discussions with patients and informed consent process. 4) Need to consult with experts in symptom relief. 5) Delivery of sedative drug(s) to reduce the level of consciousness and prevent suffering, monitoring the response of the patient. We created the definition of palliative sedation taking these points into account. In the subsequent analysis, we excluded items 2 and 4, as all patients managed at the PPCU-CM had life-limiting or life-threatening conditions and this unit is the referral paediatric palliative care unit in the region, the scope of which includes the management of refractory symptoms.

Thus, we addressed mainly 3 items in our analysis: 1. Indication 2. Consent 3. Delivery (Table 1). For item 1a, we used the guidelines for end of life care for infants, children and young people with life-limiting conditions of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of the United Kingdom.19 We selected this guidance based on methodological considerations, although other sources may be consulted to obtain more detailed information on symptom management.20,21 For item 2a, we adapted the pertinent aspects of the law on patient autonomy of Spain,22 which considers any individual aged more than 16 years free of cognitive or legal limitations, legally emancipated or deemed as such by the physician in charge competent for the purpose of decision-making. Table 2 summarises the information on the drugs and dosage corresponding to items 3a and 3b.6,23

Items in the definition of palliative sedation.

| 1. Indication | |

| a) Prior treatment for symptom management | Appropriate symptomatic treatment had been provided for the symptoms for which sedation was indicated. |

| b) Intractability requirement | One or more symptoms identified as being refractory/intractable or defined in similar terms, indicating that palliative sedation was used as a last resort. |

| 2. Consent | |

| a) Assessment of patient competence | The patient was considered competent if aged more than 16 years, legally emancipated or deemed competent by the physician in charge in the absence of any known cognitive impairment. Otherwise, the parents or legal guardians were entitled to participation in decision-making, item 2b. |

| b) Participation in process | Discussion and agreement with the consenting individual (item 2a) documented in the health record. |

| 3. Delivery | |

| a) Appropriate drug | See Table 2 |

| b) Appropriate initial dose | See Table 2 |

| c) Monitoring | Documentation of aspects that were monitored (symptoms/sedation) and the use of scales or subjective assessment. |

Drugs included in the standard and their dosage.

| Drug | Initial dose |

|---|---|

| Midazolam | 0.05 mg/kg, can be given again to a maximum total of 2 mg. |

| Thereafter, continue administering 1/4-1/3 of the cumulative dose per hour. | |

| Lorazepam | 0.05 mg/kg every 2-4 hours. |

| Levomepromazine | 0.5-1 mg/kg/day divided in 4 doses to a maximum of 75 mg/day. |

| Chlorpromazine | 1-2 mg/kg/day divided in 4 doses to a maximum of 40 mg/day |

| Haloperidol | 0.1 mg/kg/h |

| Propofol | 1 mg/kg/h |

| Thiopental | Dose of 2-5 mg/kg followed by infusion at a rate of 1-5 mg/kg/h |

| Pentobarbital | Dose of 2-3 mg/kg over 30 min (maximum rate, 0.8 mg/h) followed by infusion at a rate of 1-2 mg/kg/h |

| Dexmedetomidine | 1 µg/kg given over 10 minutes followed by infusion at 0.1-1 mcg/kg/h |

| Phenobarbital | IV: Bolus of 1-6 mg/kg (maximum, 20 mg/kg) over 20 min followed by infusion at a rate of 1 mg/kg/h |

| SC: 2.5-5 mg/kg in 24 horas, given as 1 or 2 doses (maximum, 300 mg/dose) |

IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

We defined adherence to an item (1, 2 or 3) as fulfilment of all of its subitems (a, b and c).

Phase 2: description of study universe and evaluation of the definitionWe conducted a retrospective review of the health records of deceased patients managed at the PPCU-CM in a 5-year period (January 2013-December 2017) to identify those who received palliative sedation and analyse the instances of palliative sedation delivered at the PPCU-CM.

We obtained data on deceased patients from the internal records of the PPCU-CM. We excluded patients whose records did not include a death summary (a report that summarises the care received by the patient at the PPCU-CM). We identified patients that received palliative selection applying the following criteria:

- •

Mention of the term “palliative sedation”

- •

Intentional lowering of awareness used for symptom management.

- •

Use of a sedative drug to manage a symptom described as “refractory” or “difficult to control”.

- •

Delivery of a sedative drug through intravenous infusion at an appropriate dose.

The definition of palliative sedation excluded the use of a sedative drug primarily for symptom management (benzodiazepines for management of anxiety, epileptic seizures or dyspnoea) in symptoms not considered “refractory” and in the absence of a specific mention of “palliative sedation” in the records.

To assess the need of palliative sedation in our patients, we also classified those that did not receive palliative sedation into the following groups:

- a)

Patients who did not need sedation: the health records showed adequate symptom control.

- b)

Patients in whom the need of palliative sedation could not be completely ruled out: adequate symptom control was not clearly documented in the records.

We collected data on the following variables for every patient: sex, age at time of death, classification as oncological and non-oncological patient, primary diagnosis, duration of management in the PPCU-CM and place of death. We compared the characteristics of the patients that received palliative sedation and the patients that did not.

In patients that received sedation at the PPCU-CM, we also collected data for the items used in the definition and the following variables: symptom(s) based on which sedation was considered indicated, continuous or intermittent sedation, and mild or deep sedation. If the intervention was monitored, we documented whether monitoring focused on the assessment of sedation itself and/or of the symptoms, and whether scales were used for the purpose. Lastly, we collected data on the drugs used, the maximum dose, adverse events, the reasons to discontinue sedation and whether sedation achieved comfort.

Statistical analysisWe used the software STATA® version 16.1. We compared variables in patients that received and did not receive sedation by means of parametric tests ( χ2 and Student t test to compare means) or nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank test and Mann-Whitney U test). In the descriptive analysis, we summarised the data using the median and interquartile range. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of less than 0.05.

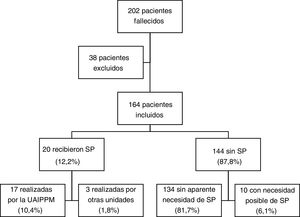

ResultsCharacteristics of the sample; comparison with control groupIn the period under study, 202 patients managed by the PPCU-CM died (Fig. 1), of whom we excluded 38 due to the absence of a death summary; 20 patients (12.2%) received palliative sedation, in 17 cases through the PPCU-CM and in 3 in other units (1 through the department of haematology, 1 through the department of oncology and 1 through the department of paediatrics). In the group of 144 patients that did not receive palliative sedation, the records indicated adequate symptom control in 93.1%, while the need for sedation could not be ruled out in 6.9%.

Table 3 compares the characteristics of patients that did and did not receive sedation. Of the 20 patients that received it, 70% were male, and the median age in this group was 11.9 years (IQR, 8.0-16.8); 12 patients (60%) had cancer (8 had extracranial solid tumours, 2 tumours of the central nervous system and 2 blood tumours), 7 (35%) had neurologic diseases (6 had static encephalopathies and 1 spinal muscular atrophy) and 1 had a polymalformative syndrome in which the major feature was bone marrow aplasia. The median duration of follow-up was 2.7 meses (IQR, 0.4-14.5). Patients who received sedation were significantly older and died at home more frequently compared to those who did not receive it. The frequency of palliative sedation was not higher in patients with cancer compared to patients with other diagnoses.

Characteristics of patients that received palliative sedation compared to those who did not. The percentages are over the total for the group (sedation vs no sedation). For the sex, disease and place of death variables we used the Pearson chi-square test. For age at time of death and place of death, we used the Wilcoxon rank test since the number of patients in the sedation group was less than 30.

| Patients given palliative sedation (n = 20) | Patients without palliative sedation (n = 144) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .58 | ||

| Male | 14 (70%) | 91(63.2%) | |

| Female | 6 | 52 | |

| Age at death (years) | 11.9 (IQR, 8.0-16.7) | 8.5 (IQR, 2.5-13.4) | .02 |

| Disease | .84 | ||

| Oncological | 12 (60%) | 83 (57.6%) | |

| Not oncological | 8 | 61 | |

| Follow-up at PPCU-CM (months) | 2.7 (IQR, 0.4-14.5) | 3.2 (IQR, 1.1-13.6) | .4 |

| Place of death | .029 | ||

| Hospital | 12 (60%) | 50 (34.7%) | |

| Home | 8 | 94 |

PPCU-CM, Paediatric Palliative Care Unit of the Community of Madrid.

PS, palliative sedation.

Of the 17 patients that received sedation through the PPCU-CM, 9 had more than 1 refractory symptom at the time sedation was initiated (Table 4). The most frequent intractable symptoms were pain (64.7%) and dyspnoea (58.8%). Four patients had agitation, in every case associated with some other symptom (pain in 3, dyspnoea in 1). One patient had convulsions and dyspnoea. Sedation was administered at hospital in 52.9% of the patients and at home in the remaining 47.1%.

Characteristics of the delivery of palliative sedation.

| Sex | Age at death | Disease | Duration FU | Setting of delivery | Symptoms | Type | Depth | Monitoring | Drug | Max dose (mg/kg/h) | Duration (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 9 y 5 m | Metastatic haemangioendothelioma | 4 m | Hospital | Dyspnoea | Symptoms | MDZ | < 1 | |||

| 2 | M | 5 m | SMA I | 4 d | Home | Dyspnoea | Symptoms | MDZ | 1 | |||

| 3 | M | 19 y | Epilepsy | 3 y 9 m | Home | Pain | Cont. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.2 | 3 | |

| Dyspnoea | HLP (+2) | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 4 | M | 15 y 1 m | Cerebral palsy | 5 d | Hospital | Dyspnoea, | Cont. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.3 | 2 | |

| Convulsions | ||||||||||||

| 5 | M | 19 y 3 m | Low-grade glioma | 9 d | Hospital | Pain | Cont. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.2 | 1 | |

| Agitation | ||||||||||||

| 6 | M | 18 y 2 m | Cerebral palsy | 1 y 8 m | Hospital | Dyspnoea | Cont. | Mild | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.3 | 4 |

| Agitation | Sedation | |||||||||||

| 7 | M | 7 y 6 m | Medulloblastoma | 9 d | Hospital | Pain | Cont. | Deep. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.17 | 1 |

| Dyspnoea | Sedation | |||||||||||

| 8 | M | 19 y 10 m | Spinocerebellar ataxia | 4 m | Hospital | Dyspnoea | Cont. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.3 | 5 | |

| type VII | ||||||||||||

| Sedation | ||||||||||||

| 9 | M | 17 y 1 m | Osteosarcoma | 1 d | Home | Pain | Cont. | Symptoms | 1 | |||

| Dyspnoea | Sedation | |||||||||||

| 10 | M | 10 y 10 m | Neuroblastoma | 6 m | Home | Pain | Cont. | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.01 | 1 | |

| Agitation | HLP | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| 11 | F | 4 y 6 m | Retinoblastoma | 1 m 10 d | Home | Pain | Int. | Mild | Symptoms | MDZ | 21 | |

| 12 | M | 9 y 7 m | Osteosarcoma | 1 m 18 d | Home | Pain | Cont. | Deep | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.05 | < 1 |

| Sedation | HLP | 0.05 | ||||||||||

| 13 | M | 4 y 11 m | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 m 18 d | Hospital | Pain | Cont. | Deep | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.2 | 1 |

| Dyspnoea | ||||||||||||

| 14 | F | 16 y 3 m | ALL | 17 d | Home | Pain | Cont. | Deep | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.25 | 3 |

| 15 | F | 11 y 9 m | Cerebral palsy | 2 y | Home | Pain | Int. | Deep | Symptoms | PPF | 1 | |

| 16 | M | 5 y 7 m | Acquired brain injury | 8 m | Hospital | Pain | Cont. | Deep | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.35 | 42 |

| Agitation | PPF (+40) | 7.3 | ||||||||||

| 17 | F | 14 y 11 m | Osteosarcoma | 1 d | Hospital | Dyspnoea | Cont. | Deep | Symptoms | MDZ | 0.1 | 1 |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; Cont., continuous; d, days; F, female; FU, follow-up; HLP, haloperidol; Int., intermittent; M, male; m, meses; MDZ, midazolam; PPF, propofol; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; y, year.

In the Drug column, the number in parenthesis indicates the number of days after initiation of palliative sedation that the second drug was added.

Of all patients that received sedation, 76.4% received continuous sedation and 11.8% intermittent sedation (missing data in 2 cases). The depth of sedation was recorded in 10 patients: deep in 8 and mild in 2. Midazolam was the most frequently used drug (88.2%), administered alone (64.7%) or combined with haloperidol (17.6%) or propofol (5.9%). One patient received propofol as monotherapy. The maximum dose for each drug was 0.35 mg/kg/h for midazolam, 0.8 mg/kg/h for haloperidol and 7.3 mg/kg/h for propofol.

In 16 cases, sedation was discontinued due to the death of the patient; the remaining patient developed septic shock that resulted in coma, a state in which sedation was no longer needed. Only one patient experienced an adverse event (mild bronchorrhoea that did not require treatment). The median duration of sedation was 1.5 days (IQR, 1.5-3.5).

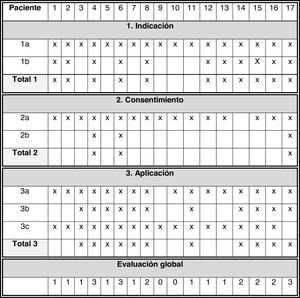

Assessment of the definitionFig. 2 presents the main results in this section:

- 1

Indication: all patients had previously received appropriate treatment (1a = 100%). In 11 patients, there was an identified refractory symptom. Adherence to item 1: 64.7%.

- 2

Informed consent: 16 patients were not considered competent to consent due to age (< 16 years) or cognitive impairment, placing the onus of consent on the legal guardians. Patient 17 (age 14 years) was deemed competent by the physician in charge and participated in the decision-making process. Patient 14 was older than 16 years and did not exhibit cognitive impairment, but there was no documentation of the patient’s participation in the consent process. For this reason, item 2a was only fulfilled in 94.1% of the patients. The informed consent process (item 2b) was only documented in 17.6% patients. Adherence to item 2: 17.6%.

- 3

Delivery of sedation: In 16 patients, the selected drug was appropriate, and in the rest it had not been documented (item 3a = 94.1%). In 11 patients, the initial dose was adequate, in 2 lower than recommended and in 4 it was not documented (item 3b = 11/17). Monitoring of symptom control (17/17) or sedation (5/17; item 3c = 17/17) was performed in every patient, but scales were not used in any case, and it was always based on subjective measures. Adherence to item 3: 64.7%.

In the overall assessment of the standard, we found that all three items had been fulfilled in 17.6% of the patients, two in 23.5%, one in 47.1% and none in 11.8%.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that describes the process of analysing palliative sedation in our region. The main findings are that sedation was given to 12% of patients, chiefly with cancer or severe neurologic disease. In most cases it was delivered by continuous infusion and through the end of life. Midazolam was the drug used most frequently. The established definition, although based on the scarce volume of literature currently available, allowed us to identify areas of improvement in our unit, mainly concerning informed consent. The main limitations of our study were its retrospective design based on the review of health records and the absence of a consensus on the definition and application of paediatric palliative sedation.

When it came to the frequency of use of palliative sedation in patients that received palliative care at the end of life, the data reported in the previous literature varies between studies, from frequencies similar to the one found in our patients17 to frequencies greater than 50%,9,24 but few studies have focused on the paediatric population. Our study suggests that the need for sedation is infrequent, although this finding may be biased, since the clinician that completes the death summary may overestimate the degree of comfort achieved in the patient. Due to the high proportion of patients with neurologic disease in our study and in the paediatric population that receives palliative care,25 the actual need of palliative care in this group may be particularly difficult to determine, as disease in these patients directly affects their ability to communicate. Furthermore, in our study, patients with cancer did not receive sedation more frequently than patients with other diseases. This diverged from the previous literature, as most articles on palliative sedation in the paediatric population focus on patient with cancer.5,7–9 While international standards have noted this heterogeneity,13 studies at the regional level are required to determine the regional epidemiology of the diseases managed by a palliative care team. In addition, access to care teams with experience in symptom management at the local level may also be a factor in the need of palliative sedation at the regional level.

Although we found significant differences in the age and setting of delivery/death in the groups that received and did not receive palliative sedation, these findings must be interpreted with caution, as the analysis was not adjusted por potential confounders. As regards the place of death, it seems reasonable that patients with less tractable symptoms would be hospitalised to monitor the patient more closely, consistent with previous studies.4 However, explaining the association of age with palliative sedation proves more challenging. Since this was not the primary objective of our study, we did not analyse this aspect. Our hypothesis is that older age correlates to a greater capacity to express suffering, which could partially explain the observed association, but more rigorous studies are necessary.

The symptoms identified in our study are among the symptoms described most frequently in the paediatric population at the end of life.26,27 In this sense, the approach to sedation in our patients had the characteristics of terminal sedation (continuous and deep).1,17 Previous studies have already described the use of palliative sedation to manage more than one refractory symptom4; the frequent presence of agitation as a second symptom could be due to agitation being secondary to the “primary” symptom, although we were unable to elucidate this aspect in our study. The application of the NICE guidance19 may place some limitations in the assessment of the management of refractory symptoms, but there is no consensus on the management of most symptoms considered difficult to treat in paediatric palliative care beyond expert recommendation.4 Midazolam was the most frequently used drug, in adherence with current recommendations in the paediatric and adult literature.1,2,6

We ought to elaborate on the cases of 2 of our patients. In patient 15, palliative sedation with propofol for management of pain was discontinued after the patient developed septic shock with a secondary decrease in the level of consciousness, and there was no evidence of an increase in pain after withdrawing sedation. Patient 16 suffered from spasticity refractory to treatment with tizanidine, intrathecal baclofen and several adjuvant analgesic drugs, leading to initiation of continuous infusion of midazolam to manage the spasticity that had to be increased to sedative doses given the lack of an alternative treatment. The patient remained stable for 40 days, after which a mixed pattern of spasticity and neural irritation recurred that did not respond to further increases in the dose of midazolam, requiring the addition of propofol as a second sedative. These cases illustrate two of the principles at the heart of palliative sedation: it should be applied only when awareness needs to be lowered by pharmacological means and it should not seek to hasten or delay the death of the patient.1,2,28 It is also important to differentiate those patients that receive a drug with a potentially sedative effect for the purpose of symptom management as opposed to sedation, which in this study was accomplished by applying the inclusion criteria and point 3b of the definition.

The established definition may be controversial, as we did not use a specific methodology and due to the decision that every item needed to be performed correctly. We made this decision based on 2 considerations. The first one is that the purpose of the standard was to identify areas of improvement. Requiring adequate fulfilment of each subitem allowed us to identify the areas with more room for improvement easily, as was the case of informed consent. The second is that the literature on paediatric patients was very scarce, which hinders establishment of a standard in regard to not only what constitutes best practice, but also customary practice. Even some of the doses presented in Table 2 are based on expert recommendations based on evidence extrapolated from the adult population due to the lack of evidence in the paediatric population.6 Thus, we believed that an analysis based on the largest possible number of items would be most fitting to describe our clinical practice.

The main limitations of our study stem from the use of retrospective clinical data. There were certain aspects (such as the informed consent process) in which the lack of fulfilment of the standard may not reflect poor clinical practice but rather inadequate documentation of this practice in the health records. This is particularly important when it comes to informed consent, regarding which our assessment was especially stringent given that the intervention under study should be based on shared decision-making, especially when it comes to patients with severe disease.29,30 Establishing the real-world need for and current practices in palliative sedation would require performance of a prospective study. Notwithstanding, the documentation of the discussion of clinical matters with patients and families is still a crucial aspect of medical practice. A study conducted in the adult population with palliative care needs found that discussion of palliative sedation was documented in 70% of the patients.31

In conclusion, our study evinces an infrequent need of palliative sedation in a population of patients receiving paediatric palliative care at the end of life. The creation of this standard allowed us to identify the informed consent process and/or its documentation as the main areas that could be improved in our unit. The changes that this finding may have caused in our unit remain to be determined once the next 5-year period is completed. Further investigation will be required to confirm the external validity of this definition.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de Noriega I, Rigal Andrés M, Martino Alba R. Análisis descriptivo de la sedación paliativa en una Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96:385–393.

Previous presentations: This study was presented as an oral communication at the III Congress of the Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos Pediátricos (March 21, 2019; Toledo, Spain) and as a poster at the 16th World Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (May 23-25, 2019; Berlin, Germany).